Keep your enemies close

Femme, Sam H. Freeman and Ng Choon Ping’s queer reframing of the neo-noir thriller, offered cinematographer James Rhodes unrivalled creative freedom in his lensing choices.

When Jules’ (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) career as a drag performer is ruined by a horrific homophobic attack, he decides to exact revenge on his closeted aggressor, Preston (George MacKay). Femme, Sam H. Freeman and Ng Choon Ping’s feature-length expansion of their award-winning 2020 short, flips the traditional hyper-masculinity of neo-noir on its head in a queer London.

While Freeman is an acclaimed screenwriter (Industry, This Is Going To Hurt) and Ng a respected director with the National Theatre, the pair were fledgling screen directors when cinematographer James Rhodes first met them in 2020. The DP has been an important collaborator ever since, but their working relationship almost wasn’t to be – until a chance phone call from a friend.

“I owe Molly Manning Walker everything,” Rhodes admits with a smile. “She rang me (in August 2020) and said, ‘Hey man, I just got contact traced. I’ve got this amazing short film tomorrow, do you want to do it?’ It was a four-day shoot, beginning the next day; she said the directors were awesome, but had never made a film before… I cleared my schedule as quickly as possible and was able to jump on it.”

Later that same day, Rhodes joined Freeman and Ng on Zoom to share his ideas and a few punchy references, including Aneil Karia’s yet-to-be Oscar-winning short The Long Goodbye. With Manning Walker’s encouragement, he was trusted to take on the Femme short – even without being involved in prep.

That risk paid off. Despite the gung-ho approach, the shoot was successful and after a SXSW premiere, the plaudits for Femme came rolling in: a London Film Festival selection followed by a BIFA win for Best Short and later a BAFTA nomination. The short’s success even caught the attention of the BBC Film, who wanted to finance a feature-length film.

Hunger to learn

Unlike his hasty introduction to the short, Rhodes enjoyed five weeks of prep in spring 2022 for the feature – although, he notes, he would regularly catch up with Freeman and Ng to brainstorm ideas in the months before shooting. Given the duo’s relative inexperience in filmmaking, the DP almost assumed the role of film mentor when it came to workflow and execution in these discussions: “They’d expertly crafted a script that was intricately woven with threads of character and detail, and both are utter movie nerds, but without a depth of experience getting from A to B, I certainly felt privileged to be on that journey with them, finding the tools they needed to get to the film they were trying to make.”

Working with co-directors added a fresh dynamic. “Having an extra brain there influences slightly different tangents,” Rhodes muses. “It was a catalyst to really creative thinking and I really valued it because of that. And because of the diversities in their professional backgrounds, they both brought really interesting points of view. It also meant they could divide and conquer in working practice on set. I wouldn’t change it for anything.”

References discussed in prep included the Safdie Brothers works Good Time and Uncut Gems. “Good Time was like the North Star for Sam and Ping,” says the DP. “It was a reference for so many reasons, including the stress and chaos of the film – that was something we were striving for. A lot of that comes from the mixed lighting sources in the scenes which were chaotic, scrappy and messy, but also from the camera behaviour – always feeling that you’re with the actors, but equally feeling slightly blinkered, unpredictable and a bit aggressive. We tried to intertwine the audience in the experiences of both characters in that same way.”

Rhodes encouraged the directors to use different lenses and mixed formats to subtly portray the narrative arcs of the two main characters, Jules and Preston. While Jules and Preston begin the film as protagonist and antagonist respectively, midway through their roles start to shift, before another twist at the end of the film throws the audience off. “We always said our biggest challenge was going to be making the audience hate Preston, but ultimately making them feel sorry for him – that was something I thought about a lot,” says the DP.

At the beginning of the film, Jules’ world is “very anamorphic, drawing on the premise that anamorphic means controlled compositions with controlled movements”, with Rhodes leaning on a 50mm super high-speed Panavision lens. As the story moves into Preston’s world, Rhodes opts for the S35 spherical PVintage set, with a “nod to the language of documentaries and their responsiveness to the environment; its own premise that anything could happen at anytime. Later, when we become more sympathetic with Preston, and Jules is gaining some control, I returned to the earlier lens logic and invited Preston into that set of rules we had for Jules’ lensing.”

There were similar considerations when it came to camera movement. At the beginning, when Jules is in his element as queen Aphrodite at his drag show, the camera is very controlled, on Steadicam and flowing confidently throughout the environment. “But when Jules loses all confidence and Aphrodite goes away, we were pretty much always handheld with a tiny bit of static,” Rhodes continues. “We never really got into the tripod world because Ping was very sensitive to maintaining the ‘chaos’.”

The filmmakers kept the environment as 360-degree as possible, and with rooms adjoining so Rhodes – who operated all but the Steadicam shots – could go from one room to another with the cast and enjoy the freedom of handheld. It’s a skill that he compares to his days in a band: “I carry a lot of my experience playing a musical instrument in a band into my handheld operating: So much of what the camera ends up doing is down to some sort of subconscious flow state of performing together. That kind of authenticity of having a camera mimic the behaviour of the cast is what I’m always striving for.”

For the Femme short Rhodes inherited Manning Walker’s kit, the Alexa Mini and Master Primes, but opted for the Sony Venice at 2500 ISO as his camera of choice for the feature. “I really liked how the Rialto enabled certain things like the car shots,” he explains. “It meant we could rig shots more easily, especially on the interior of the vehicle with limited space. That smaller profile made a difference.”

Key grip Tom Stansfield built a special rig for the Venice’s Rialto extension (affectionately dubbed ‘the ball and chain’), Rhodes remembers. “Because we did a lot of Rialto in the small bedroom location, Tom came up with a special system – a little trolley for it – which was really cool, because the camera body sat vertically on this post, attached to a small trolley wheelbase, and the ‘ball and chain’ could very easily be rolled to new positions as we worked around a scene.”

Authenticity in lighting

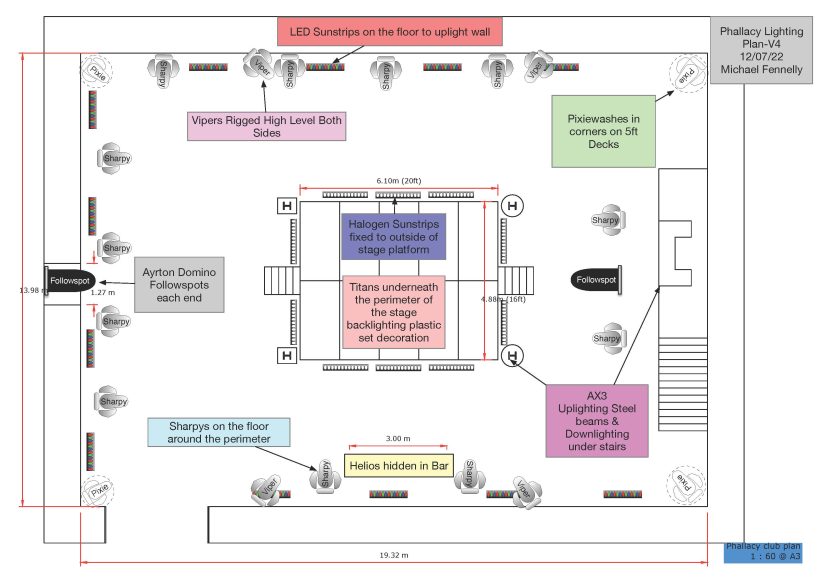

When lighting Femme, the temptation to ramp up the vibe of the drag shows was strong. After all, Rhodes’ roots are in live concert films – a recent example being the Elton John at Dodger Stadium with a 28-camera setup(!) – and at first, he wanted to draw on this experience for Aphrodite’s appearances. However, he ultimately decided the shows should feel more DIY and not so flashy, as a real setup would be. “The further we got into prep for that world, it felt that the DIY approach should be something that we should retain and not get too sucked into making it look cooler or flashier. There are scaffolding poles everywhere, it’s intentionally really textured and really DIY thanks to Chris (Melgram)’s production design.”

The DP is a fan of soft-top lighting on drama sets, which allow him to easily modulate contrasts and lift environments as needed. In Jules’ apartment they used six 4×4 LiteMat Spectrums on the ceiling; during the party scenes, this allowed the desk operator to dial in a colour wash that cycled through two or three selected hues and to give it a very soft wash and dynamic lighting. “I’m sure it was a pain in the ass in the edit because none of it was time-coded to the dialogue,” he jokes.

One especially useful light was the Rosco DMG Dash: an iPhone-sized, modifiable LED panel. Rhodes describes it as an “invaluable” addition to the project, placing it on top of the camera as a the top light – something he’s normally “completely allergic” to.

The original intensity of the light didn’t really go low enough, so he asked gaffer Michael Fennelly to cut some ND as a permanent addition to the light: “Remember we’re at 2500 ISO, a hair off wide open, and so you’re working at 1% and you want a tiny bit more, you go to 2% and the light output doubles – but you just want a fraction of that. So we knocked it right down with the ND and now we’re working at 50% and can subtly increase to 52%.”

The Dash was useful for a delicate eye light, and catching some texture in Nathan Stewart-Jarrett’s skin. “Lighting Nathan was such a joy because he always looks amazing. I think it’s always challenging lighting different skin tones in the same frame. Everyone always talks about lighting dark skin, when actually it’s about how you light skin (in general). Skin in dark and light tones have very similar qualities in a specular nature, so I started to concentrate only on this. I’d put soft lights in positions close to camera at very low intensities where they would create subtle specular reflections, which would read as texture in the skin on camera, but not necessarily showing skin tones that are technically ‘well exposed’. The Rosco Dash was a massive asset for this because in a tight set with no room for a larger source I could always have it rigged above the lens.”

The grade was done remotely by Rhodes’ core collaborator Joseph Bicknell of Company 3, who is based in New York. “I knew he had to be in my corner for this, because he does really special work and I trust his eye,” says the DP.

In testing, the filmmakers brought in a stand-in model for Stewart-Jarrett so they could nail his skin tone, then sent some lighting looks, some colour palettes and cherry-picked lenses off to Bicknell to see what he made of them. “I think I dialled in colour temperature here and there but sat with one LUT throughout,” notes Rhodes. “I don’t think I changed the colour temperature too much because we were mostly a nocturnal world.”

Unusually, Bicknell chipped away at the grade over weeks rather than having one blocked-out grading session. “We weren’t spending tonnes of time in contact with him but I think it meant that the work was a little more nuanced and considered, than if you’re trying to cram into a week’s grade,” says the DP.

Femme is Rhodes’ first “proper” feature, as he calls it, after two non-starters – and with a nomination in the Best Cinematography category among its 11 BIFA nods, it’s certainly made an impact. Are there any lessons he’ll take onto future productions? “I’d push for more prep days with the cast,” he admits. “I’d love to twist the production’s arm into saying, ‘Can we do a set build and shoot the first two days and then throw it away?’ That’s a big one, which is obviously not always possible because of cast availability, and it obviously costs a lot of money which feels like is being thrown away. But I think you reap the rewards from that in quality and consistency from day one if you’ve already settled into the relationships and what the voice of the film is already.”

One thing we wouldn’t change is his “incredible” team. The DP caught COVID in week four of the shoot, so lensed remotely until getting the all-clear. Aaron Rogers stepped in for a few days to operate, and Fraser Rigg did a day too. Another key colleague was focus puller Vlassis Skoulis. “He enables me to do absolutely anything I want to with the camera. Having that confidence is so freeing and I couldn’t thank Vlassis more for making that possible. I know a lot of focus pullers are just as skilled, but the trust between us is huge. I couldn’t do it without him.”

Signature Entertainment presents Femme exclusively in cinemas from 1 December.