ARTISTIC ADVENTURE

Old and new techniques were magically merged in the filming of Yorgos Lanthimos’ award-winning Poor Things. Robbie Ryan BSC ISC shares the creatively ambitious journey of discovery the filmmakers embarked on when building a unique and wild world of wonder.

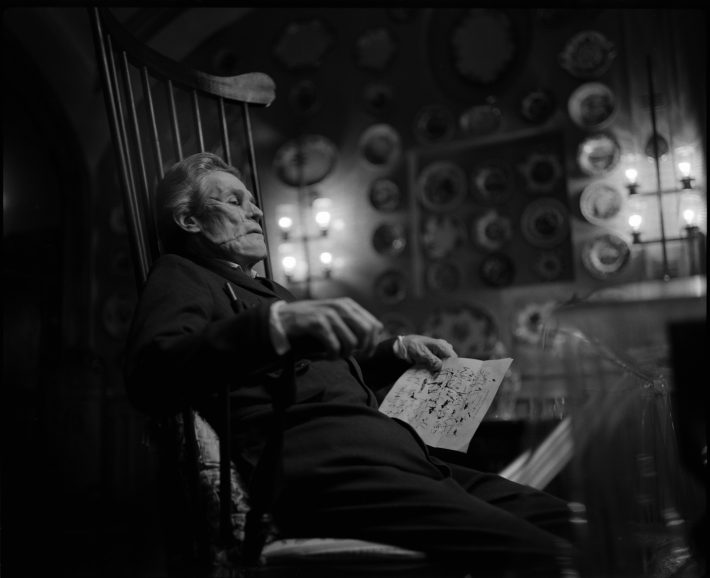

“Every day was a crazy music video, I always thought,” reflects Robbie Ryan BSC ISC about his latest film Poor Things, his second project with Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos, following 2018’s The Favourite, which saw the Irish cinematographer nominated for an Academy Award. While that Queen Anne-era drama might be off-kilter, it’s nothing compared to Poor Things, an adaptation of Alasdair Gray’s prize-winning 1992 novel about a Victorian scientist named Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe) who resurrects a female suicide victim, re-animating her with the brain of her baby and naming her Bella (Emma Stone).

Blessed with such a curious Frankenstein-like tale, Lanthimos and his team set out to conjure up something entirely unique. Already winning the Venice Film Festival’s top prize, the Golden Lion, when it premiered there in September, it’s safe to say that the jury, led by Damien Chazelle, has probably never seen a film like it. “The best way to say it is the ambition was very high. So even if you didn’t reach that ambition, the lower hit was still pretty interesting,” says Ryan, speaking over video from his home. “It was always going to be a step into an unusual world, in every respect.”

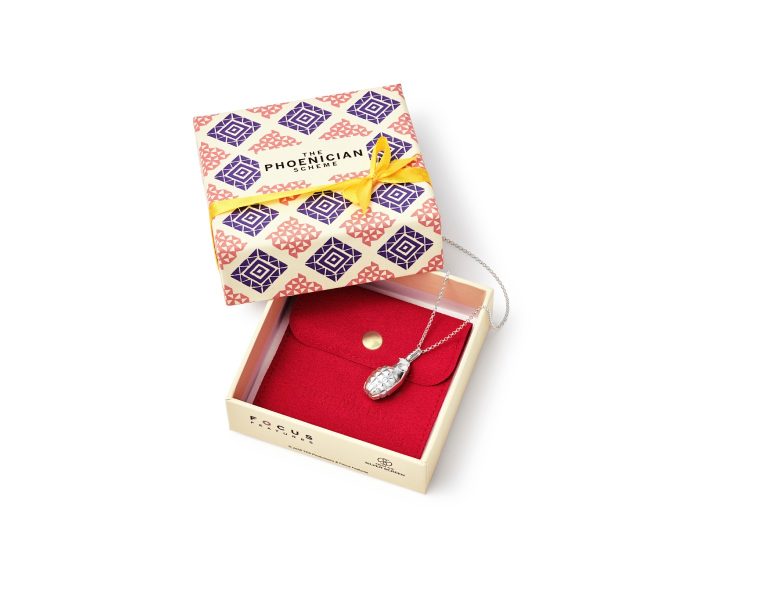

Far from your typical period piece, Poor Things is a kaleidoscopic phantasmagoria, with Ryan called upon to utilise old and new filmmaking techniques. First and foremost, Lanthimos wanted to shoot on film. “Ever since [his 2015 fable] The Lobster, Yorgos has said he’s never doing a film on digital again. And he doesn’t even take stills on digital anymore.” Every day, in between takes, Lanthimos used a large-format camera, the Chamonix, to take stills of his actors; at night, he’d develop them. “A lot of the promotional photography are Yorgos’ pictures, which are stunning,” says Ryan.

This unusual, handcrafted approach to publicity rather reflects the film as a whole. Using a mix of stocks, including black-and-white, Ryan shot about thirty percent of the film on Ektachrome, including the sequence where Bella jumps from London’s Tower Bridge to her death. The scene’s rich midnight blue hue came from this rare stock. “Kodak brought it back on the market,” says Ryan. “I’m delighted they did it. But they re-introduced it into the world as a 16mm stock and then there are no labs [almost] that can actually process it!”

As well as Kodak Ektachrome 100D 5294 colour reversal and Kodak Vision3 5219, Ryan used Kodak Double-X 5222 for the movie’s opening black-and-white sequences.

With the production shooting at Origo Studios in Hungary, Ryan’s team was fortunately able to find a lab in Germany that was capable of processing Ektachrome: the Berlin-based Andec Filmtechnik, managed by Ludwig Draser. “It was a very bespoke type of lab. He wasn’t used to a proper Hollywood production knocking on his door. He’d have a few people with a couple of rolls of film that he’d process every now and again,” says Ryan, who also praises producer Kasia Malipan for managing the workflow and getting the rushes developed daily and returned to Budapest, as the shoot was ongoing.

“Excited but terrified” is how Ryan describes the experience of using the stock. “Ektachrome is basically 100 ASA, so it’s very slow stock,” he says. With little time to test it, Ryan says the fear factor was quite high. “They say when you shoot Ektachrome, if you don’t get the blacks right, if you don’t get the exposure right, and you’re a bit underexposed, everything is irretrievable. And we had to light it quite a lot…there were one or two occasions where I did get underexposed and luckily the scanners that we scanned it on had a little bit more information in the black, so we were able to retain some of the black information.”

In addition, Cinelab handled the 4K film scanning and creation of film deliverables and prints.

Ektachrome aside, Ryan did undertake a lengthy twelve weeks of prep, testing out lenses, cameras, and formats with the help of Manfred Jahn from ARRI. “We tried 65mm for a bit, and that was nice, but we didn’t end up using that. But because the aspect ratio of the film is 1.66:1, Yorgos was like ‘Why don’t we try VistaVision?’ I was like, ‘What?’ I thought VistaVision was widescreen. No, it’s 1.66. So, we ended up being really excited about that.” With Lanthimos adamant that he doesn’t do Additional Dialogue Replacement in postproduction, however, it meant the VistaVision camera could only be used for scenes where capturing dialogue on set wasn’t an issue.

This included the re-animation scene when Bella is brought back to life, with Ryan shooting on a Beau Cam VistaVision. “It’s an ARRI camera that’s been adapted to turn into a VistaVision camera. It’s like a Frankenstein camera! They re-adapted it to fit a workhorse miniatures camera. And it had its quirks.” Which led to happy accidents, like the moment Stone’s character wakes up. “The camera started running out of battery…because that’s happening, that means the film is still going through, but it’s going through slower, which means you’re going at a slower frame rate, which gives it this really kind of weird animation. It looks like it’s sped up, and it was only purely by a mistake.”

Given Lanthimos’ dislike of ADR, and the considerable dialogue as Bella begins to explore both her body and the world around her, the majority of the film was shot on ARRI cameras, including the Arricam ST, “the workhorse” of the production, as Ryan puts it. “It’s such a brilliant camera. I’m a massive fan of it. It’s just ARRI at their best, very straightforward, very consistent and very quiet.” Curiously, the choice of camera or stock wasn’t something Ryan and Lanthimos discussed much. “Me and Yorgos…we always talk about lenses. We don’t talk about much more than lenses!”

Expanding reality

The film’s lens choice may well be the defining characteristic of Poor Things, contributing to the film’s unique visual feel. In Baxter’s laboratory, the filmmakers deploy an 8mm Nikkor lens, giving the scene a distinct but distorted quality. “I love the way everybody remembers the very odd fisheye because it’s quite obviously a statement type of a lens,” says Ryan, who points out that the film in actual fact utilises an array of different optics, from a wide-angle 10mm Zeiss lens to a 4mm Optex Prime, used to create a porthole-style effect. “Yorgos was keen to try to do that because he’d seen photography of the time. And I said, ‘Well, why don’t we try and use a 16mm lens that’s made for 16mm…and we use it on the 35mm, because then it won’t cover the full negative and you’ll get that heavy vignette [look].’”

All this experimentation, echoing the work of Dr. Godwin Baxter himself, helped create Poor Things’ stunning aesthetic, a film that is far removed from the starchiness of most Victorian dramas. Ryan also put the Zeiss Master Zoom lens to good use. “We zoomed all time,” he says. “A wide-angle lens, for me, is definitely the easiest lens to work with. Whereas with the zoom lens, I had to work quite a lot more. I tested mostly zooms on this film, because if you get the zoom wrong, the whole shot goes wrong. So, it was very much the thing I remember most from the shoot…trying to get those zooms right.”

Ryan also used 58mm Petzval lenses (formally used on film projectors) which were ideal to recreate the look of early photography and what the cinematographer calls the “magical softness” of those images. These aged lenses were hardly the only old-school technique the film employed; miniatures were used, for example, to recreate the ocean liner that Bella and her male companion Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo) journey on after she leaves London for Europe. “There’s a fakery,” he admits. “You’re not trying to make a realist film here. It’s an expansion of reality.”

Aiding this was cutting-edge technology too, with Ryan using virtual production techniques to help create the views from the boat, working with specialists such as virtual production supervisor Adrian Weber. “For the cruise ship, Yorgos was always very keen to try out an LED backdrop, because then we could have the waves moving and the clouds moving. And it was a small enough set that we could have a big wall of video that would then make it feel like you didn’t have to do so much post. Ironically, you always do a lot of post with that because of the nature of Yorgos’ lens choice where you’d have a wide lens, so you’d see the ceiling anyway. So, you have to hide that. But I do think the LED wall was a good choice. And from my perspective very interesting to work with that technology.”

Ryan calls it a “moving painted backdrop”, essentially, one that measured 70 metres long by 20 metres high. “Technically, it was difficult because obviously, it’s an LED wall. But if you have any other lights – and we are shooting on Ektachrome, so I need a tonne of lights – that spillage of light is really painful, because it makes the LED wall lose its punch. So, you’re kind of having to balance out so much all the time…it was a technical head wreck to try to keep the light on the deck, but not on the screen. And the fact that the deck of the ship was only probably four metres away from the LED wall made it really very difficult to stop this light spill, which made my life hell!”

Among his crucial team members, Ryan credits gaffer Andy Cole, who he’s worked with on everything from The Favourite to Ken Loach’s Jimmy’s Hall, and Gromek Molnár. “The two of them doubled up and they had a tough job, it was a lot of lighting. Those sets were huge, we had to basically build skies above them. So, some sets had upwards of 700 [ARRI] SkyPanels, which to me was totally new territory.” Ryan wasn’t afraid to integrate the practical lighting on the sets created by production designers Shona Heath and James Price either, including tungsten bulbs, which weren’t in common use until after the Victorian period.

The cinematographer also pays tribute to grip Attila Szûcs and his team, who introduced him to Delta Track. With Ryan operating the camera – all dolly, not handheld – this modular, versatile track was ideally suited to swiftly being laid down in the tightly-constructed sets in the studio. “When you’re on a film set speed is of the essence,” he adds. “So, it was really, really invaluable.”

Everywhere you looked, it was a film that brought together artistic innovation. “For every department, it was a real step in a different direction,” concludes Ryan. “We were all learning as we went. Everybody was supporting each other. There are a lot of mistakes made along the way but because the ambitions were so high, I think a lot of those mistakes got swallowed up by how great the drive was to get an interesting project finished.”

Poor Things opens in cinemas on January 12th.