VERITE VIRTUOSO

Fresh from being honoured with the Pierre Angénieux Tribute at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Barry Ackroyd BSC reflects on his celebrated career spanning both documentaries and narrative.

As a teenager, Barry Ackroyd BSC wanted to be a sculptor. School teachers said he was good with his hands. Which he was, only he wanted to use his brain too.

“They knew I was smart but not that I might be dyslexic, so when I failed exams they suggested I did something with my hands. That was half true, but I also hoped to use by mind and art was the secret.”

As a filmmaker he says he always wanted to put politics into stories and that’s evident in his incredible body of documentaries from Sunday and Hillsborough – recreations of, respectively, the 1972 Derry and 1989 football stadium disasters – to Nick Broomfield’s remarkable 1991 South African exposé, The Leader, The Driver and The Driver’s Wife and the 1996 Academy Award-winning Anne Frank Remembered.

It’s also there in his dramatic work, notably in a dozen collaborations with Ken Loach and in Hollywood movies packing a political punch, including the folly of the 2008 financial crash chronicled in The Big Short and Battle in Seattle centred on protests against the World Trade Organisation.

“I am sculptural in the sense of being three dimensional on screen coupled with a genuine passion for the subject. At least, that is what I aim for.”

The art of storytelling

From a working-class background in Oldham, “without access to huge cultural influences”, Ackroyd left school at 16 when the typical job path would have been straight into a factory. Instead, his art teacher suggested he go to art school.

After Rochdale college (“a fantastic place that opened my mind”) he progressed to a BA at a fine art school in Portsmouth which also had a small film section.

“It was here I understood that, along with the editor, cinematography is an art form unique to cinema. Shooting the film was even more integral to the process of creating a film than the director.”

With fellow students he shot a biographical drama in Devon, his first feature, and even blagged his way onto the set of Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975) to shoot a ‘making-of’ film.

“My first break was working for stills photographer and director Andrew Maclear including following musician Randy Newman on a European concert tour.”

The early 1970s was a golden era for British documentary filming. Chris Menges BSC ASC was an early influence. Ackroyd followed in his footsteps working for Dispatches, Granada and with freelance teams, travelling to over 50 countries shooting in conflict areas including the Sudan, China, Cambodia, and the Arab world.

“Getting assignments in all these places, gathering information, and working my way from assisting to DP was a great education. The lessons I learned then are what I tried to apply to my cinematography even today.”

He worked with Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC on trips to South Sudan and another documentary about Van Morrison and assisted Ivan Strasburg BSC and Mike Fox BSC. He paired that experience with his appreciation for Nouvelle Vague filmmakers and American documentary makers D.A. Pennebaker, Richard Leacock, and Robert Drew.

“They were using the camera as an extension of themselves, stripping the camera into a new ergonomic that enabled you to react freeform to a sound or a look. Raoul Coutard [Jean-Luc Godard’s cinematographer] and Néstor Almendros [ASC] were so adept and unafraid. Chris Menges dared to walk down pitch-black corridors and keep the camera turning. I tell students now that if you want to be a cinematographer in the style I appreciate, go watch Don’t Look Back (Pennebaker’s 1967 Bob Dylan observational documentary). I applied all those theories and principals of the documentary to making feature films.”

There was a third motivational force too.

“I remember as a teenager thinking that I could never make films because I am not one of them. You’d see British thespians playing working-class people and I just thought that was out of my league. Then I saw Kes which was set in a secondary school nearly identical to the one I went to. It told me that if there are films about people like me then I can be a part of making films.”

That prophesy was realised in 1991 when Ackroyd got a call from Ken Loach following a recommendation by Menges.

“My daughter had just been born and we’d just moved into a house in Hackney. I was so busy I said to my wife when the phone rang that I don’t want to do this. When Ken introduced himself, I quickly said, ‘Oh yes I can!’ The point about Ken Loach is that he dared to make films with people like me.”

Loach met his new cinematographer on a bridge over the M1. “He doesn’t like to interview you or go for coffee and talk cinema. We met between Birmingham and Leicester. I brought the camera Ken got me to shoot the only thing we could – traffic. It was my audition.”

Set in London and starring Robert Carlyle and Ricky Tomlinson as builders, Riff Raff was the start of a lifelong friendship which has taken in 12 features including Carla’s Song, AE Fond Kiss and 2006 Palme d’Or winner The Wind that Shakes the Barley.

The first three (Riff Raff, Raining Stones, Ladybird Ladybird) “were a complete learning process and really influenced me,” the DP says. “I shot those with my Aaton camera and loaded the gear each morning into the back of my Citroën GS.”

Making his name

To mark the 30th anniversary of the Derry killings in 2002, Ackroyd lit Sunday for director Charles McDougall while director Paul Greengrass was making Bloody Sunday with Ivan Strasburg.

“I was shocked when Paul called me to do United 93,” says Ackroyd of the 2006 re-enactment of the terrorist plane hijacking. “I had no idea how to do it. What I could offer was to go back to my doc days and shoot, reload, change position, and shoot again. We decided on two cameras, one low down at seat level on a dolly track and one I operated handheld with variable primes as we’re being thrown around on the plane on a gimbal. We only had four-minute mags, so we planted a mag down the plane and shot and overlapped the two cameras. We’d duck into the seat, change the mag, carry on shooting which we did for about 50 minutes non-stop.

“Instead of breaking the story into small shots we made it run because it was a cinematic piece of time.”

They teamed up again for Green Zone (2010), starring Matt Damon; Captain Phillips (2013), which earned Ackroyd ASC and BAFTA award nominations; and action thriller Jason Bourne (2016).

All displayed the handheld verisimilitude to action bred on documentaries. In Captain Phillips for example, star Tom Hanks hadn’t met his adversary played by Barkhad Abdi until the scene filmed on the ship’s bridge.

“In a way, this is a lift from Ken Loach in that the only cinema you can trust is when you capture the moment. In a documentary you only get one chance to capture the moment, you don’t get rehearsals.”

An even more spontaneous moment occurred at the end of that film. They had shot three different versions of the ending including one with Phillips at home in Boston and another on the US Navy ship.

“It was pointed out to us by the naval officers that the real protocol for what had happened to Captain Phillips would be to go see the medic. So that’s what we filmed, with the ship’s real medic. Tom didn’t know what questions he was going to be asked and his confusion and shock illustrate the character’s trauma. Holding onto someone’s reaction can be just as important as a line of dialogue.”

Ackroyd’s work on United 93 was admired by Kathryn Bigelow, who hired him to shoot The Hurt Locker in 2008, and Adam McKay, who wanted the Brit for his comedy drama The Big Short (2015).

“I’d just finished Battle in Seattle on Super16mm, and I was very keen on using 16mm for Hurt Locker,” he says. “It’s cheaper than 35mm of course and so enables you have to have more cameras and to be nimbler. We put four in most scenes which really gave us the freedom to dig into that story and move at the fast pace I like.”

For the tense drama about bomb disposal teams in Iraq, Ackroyd received an Academy Award and Bafta nomination. Nonetheless, he was shocked at how well it was received.

“I thought the unusual episodic structure might not play to large audiences but perhaps what saved it were the tremendous performances and the slow-motion shots showing what happens in the kill zone around exploding ordnance.”

Political pictures

Most of Ackroyd’s projects show a clear political sensibility. Arguably these pictures are the ones he is more passionate about and therefore where his best work shines. Asked which offers he has turned down and he reveals he was on the point of shooting Zero Dark Thirty for Bigelow about the hunt for Osama Bin Laden when Bin Laden was captured and killed by US special forces.

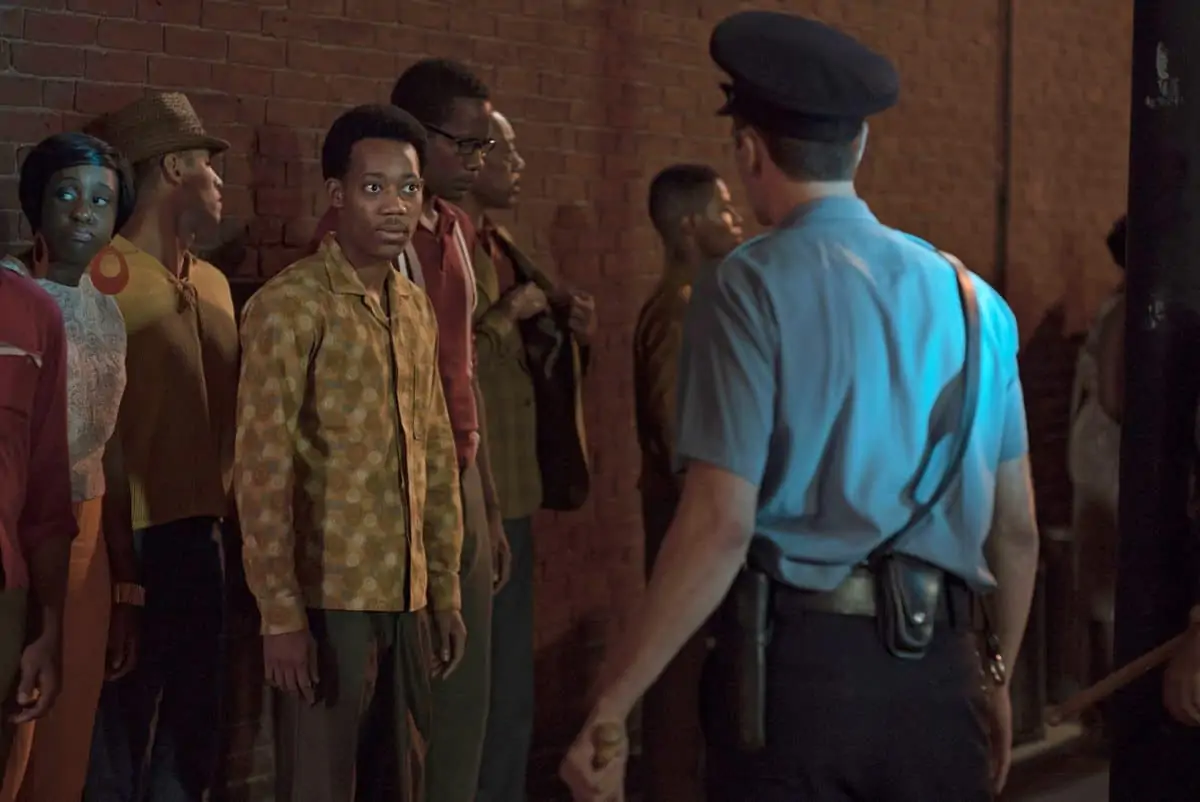

“I wasn’t sure how much influence we were then going to get from the military to tell their point of view,” he says, though he later went on to shoot Bigelow’s race crime drama Detroit (2017).

McKay wanted him to shoot Don’t Look Up, the 2021 satire on ecological disaster, but something about the script wasn’t quite to Ackroyd’s taste.

He was also offered Succession but was too busy to take on the HBO drama, although the style of the show is Ackroyd-esque. “I don’t quite throw a zoom around like that,” he says. “It should be about how you look at and listen to the world.”

Nonetheless he is proud that Hurt Locker has become a totem for a style of cinema that Ackroyd has mastered. In the wake of the film, he was offered a lot of “gung ho” macho movies and some by stunt coordinators-turned-directors who felt Ackroyd’s style suited their own.

“But stunt directors are not great directors. They just want to film action.”

One of the few concessions to more conventional Hollywood action is The Old Guard, a Netflix-funded and female-starring and directed thriller with Charlize Theron, KiKi Layne, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Matthias Schoenarts. Ackroyd shot some scenes on the original and recently shot the sequel.

“Charlize Theron is an old friend from when we met on Battle in Seattle,” he says of Theron, who is also a producer on the project. Other films they’ve made together include The Last Face, directed by Sean Penn, and Bombshell, for which Theron received an Oscar nomination for portraying Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly.

His most recent film was the Whitney Houston biopic I Wanna Dance with Somebody, starring Naomi Ackie and directed by Kasi Lemmons.

After dutifully guiding the BSC as President between 2014-2018, Ackroyd is now looking for the next project to grab his attention.

“I’ve never been good at asking for a job,” he says. “I want something that’s really good. It could be like Coriolanus (the 2011 adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy directed by Ralph Fiennes), or a political thriller that brings down the government and brings about a better world.”