TROUBLE IN PARADISE

Canadian cinematographer Karim Hussain CSC shares his passion for the horror genre, and how Infinity Pool marks the next part of a visual trilogy where rules and practical techniques established through earlier collaborations with writer-director Brandon Cronenberg were taken to new heights.

Since his introduction to the world of filmmaking, the honesty at the heart of horror movies has drawn Karim Hussain CSC (Antiviral, Orphan: First Kill, Random Acts of Violence) to work in this genre, finding it to “frequently start at a level most movies stop.” As the world can be a “challenging and extreme place, and there are many dark truths about humanity”, the cinematographer enjoys films which explore this, and begin with a less fearful canvas than other genres.

Hussain and writer-director Brandon Cronenberg’s shared passion for horror has led them to create thrilling and chilling productions such as 2020 science-fiction psychological horror feature, Possessor (profiled in British Cinematographer issue 102) and their most recent film within this genre, Infinity Pool – a commentary on extreme hedonism merging body horror, cloning, and tourism to terrifying effect.

The film follows struggling writer James (Alexander Skarsgård) who, searching for inspiration, goes on holiday with wife Em (Cleopatra Coleman) to a seemingly idyllic resort in the fictional country of Li Tolqa. Befriended by Gabi (Mia Goth) and her husband Alban (Jalil Lespert), the couple join them on a daytrip, leading to James’ arrest for a drunk-driving accident. James learns the local authorities’ punishment for tourists committing such crimes is execution by the victim’s family unless they are wealthy enough to pay for a cloned version of themselves to be executed instead.

Following his clone’s execution, James joins a gang of wild and depraved tourists who have gone through the same experience. As James and the group spiral out of control, he discovers Li Tolqa’s dark and indulgent culture of exploitation.

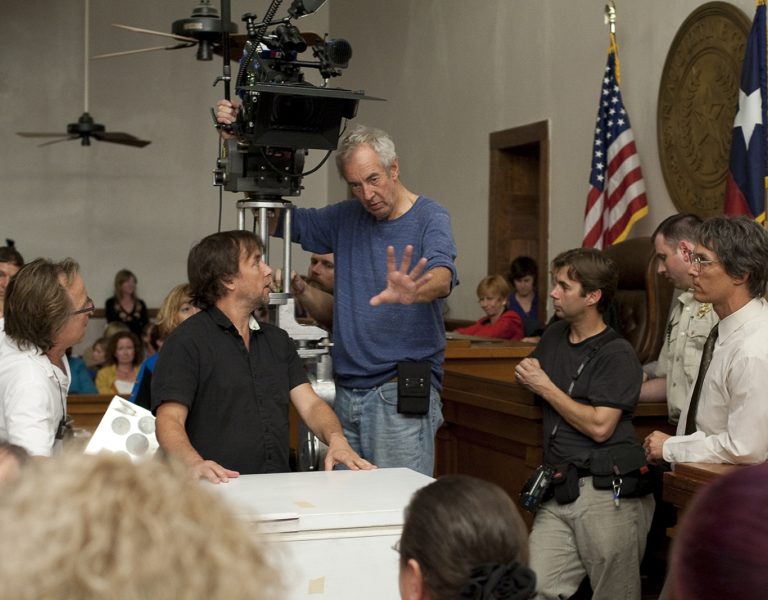

When telling such stories on screen, Hussain and Cronenberg’s relationship differs to some director-cinematographer collaborations as they are good friends, allowing them to develop movies from an early stage. “With Brandon, it’s almost like being a member of a band opposed to being a for hire cinematographer,” says Hussain.

Infinity Pool’s look and feel was spawned when Cronenberg and Hussain created previous productions Possessor, 2019 short Please Speak Continuously and Describe Your Experiences as They Come to You and music videos for band Animalia. This process saw them experiment with ambitious techniques including practical projection vortexes and unusual colour effects.

“Infinity Pool is the last piece of a visual trilogy where the rules we established are taken to an extreme through practical hallucination effects. It’s about as far as we can go with that look,” says Hussain. “Opposed to Possessor’s mix of handheld and Steadicam, and different levels of depth of field depending on the psychological state of the protagonist, in Infinity Pool we shot everything wide open to create a shallow depth of field sense of paranoia. While the first draft of Infinity Pool is pretty close to what ultimately was shot, you wouldn’t recognise Possessor from the early draft.”

Before shooting Possessor, Hussain, Cronenberg, and producers Rob Cotterill and Karen Harnisch went on a location scouting trip to Croatia, and Hungary, where Infinity Pool was shot. Encountering various challenges led them to adjust the screenplay to suit the locations.

“We intercut between Hungary – which is relatively cold and used for a few select interiors, and the world of the city outside of the resort – and a more populated area shot on a tourist resort in Croatia,” says Hussain. “It wasn’t supposed to be challenging but that summer in Croatia during the pandemic, they decided COVID didn’t exist. Everybody came to the location we’d chosen, and it became a functioning, highly attended resort. Some tourists just became extras, but it was difficult to accomplish, especially in the 25 days available.”

Inducing anxiety

Infinity Pool is a tale of contrasts – the opening calmer scenes of an idyllic resort far removed from the extreme sequences that follow. For Hussain, however, the most frightening part of the film is the beginning “because it’s supposed to be so normal and banal yet there’s something disconcerting about it,” achieved through techniques such as a rotating camera.

Whereas a picture postcard world is normally saturated and uses deep focus to show off the idyllic landscape, Infinity Pool’s is more muted. “It needed to be anxiety inducing as the story is about the illusion of this perfect place presented to tourists when the reality is dark, and abusive towards the local populace for the government’s financial gain,” says Hussain, who wanted to avoid too many vivid colours in the resort exteriors. When the film moved towards the truth of the situation, richer colours such as popping reds and deeper yellow emerge.

Vintage lenses helped achieve the desired look including Canon K35s and Hussain’s prized 1970 25-250mm Angénieux he owns (referring to it as “Lucky Pierre”) and which was used extensively for Possessor. “The lens is used even more in Infinity Pool for the disconcerting, extreme close-ups. The techniques change when the hallucinations begin, the doubling chamber appears and there’s an extreme use of montage. All those shots are original rather than sourced, frequently rephotographed practically in post,” says the cinematographer.

“As everything in Infinity Pool is ironic, we approach some of the framing and shots from this perspective. It’s supposed to be this wonderful vacation at the start – everything’s great, yet everything’s a secret and a lie. So, through the framing and shallow depth of field there was always a secret hidden in the corner of frame.”

Rack focus was utilised alongside the Cinefade camera accessory that allows gradual transition between deep and shallow depth of field at constant exposure to accentuate drama. Cinefade was also often used as a remotely controlled mechanical variable ND. As Cinefade “adds a slight green cast” this aided Hussain in creating a “sensation of evil in the beautiful Croatian resort.”

A visual director

Once Cronenberg had discussed the frames with A camera operator Yoann Malnati and B camera operator and second unit DP Agnesh Pakozdi, the director used a phone and Artemis Pro digital smartphone viewfinder to capture the exact frame he wanted. Adopting a visual approach in prep, everything is meticulously planned, with every decision going through Cronenberg.

“He’s an incredibly visual director, especially in the hallucination sequences when we developed techniques using a long lens, and a split field diopter handheld in front of that lens with a piece of dichroic film taped around it,” says Hussain. “Dichroic film is a gel containing all spectrums of colour, so the colour changes depending on the angle you bend it or look at it.”

For many hallucination sequences, Hussain and Cronenberg took the original rushes, reprojected them in the cinematographer’s living room – a tradition of theirs developed when making Possessor – and photographed it with a Helios 58mm to create a “softer, weird feeling.” Hussain operated the camera and took care of the playback and techniques while Brandon, “much like a puppeteer of colour, focus and light, was in front of the lens with the split field diopter and shining a flashlight throughout the dichroic film.”

Following experiments with dichroic film and dichroic glass with production designer Zhosa Mackenzie and art director John O’Regan, mirror boxes were built in Hungary. When Alexander Skarsgård’s character James is in the doubling chamber, the effect of him doubling – like in an art gallery infinity room – was created live with the mirror boxes.

“To shoot an infinity room without seeing the cameras, you have to shoot through a two-way mirror,” explains Hussain. “There must be quite a lot of light coming into the infinity room, usually from the ceiling, and that light is reflected everywhere and becomes part of the technique.”

To make parts of the image move in and out of focus, the split field diopter was moved through the centre plane of the lens. “Those sequences don’t feel like normal overlays, or anything inherently baked into the image,” says Hussain. “They’re live opticals with human movement you wouldn’t otherwise have.”

The filmmakers shot multiple takes, some with more colour, more movement of light, or experimenting with projection vortexes. “Particularly in the hallucination sequences in the drug-induced orgy scene, much of that was a feed from the camera going into a projector live projecting over them to produce more texture and strange vortexes in the projection loop. We then rephotographed that material and sometimes in the edit, they went back to the camera original footage for a few frames, and then returned to the rephotographed material.”

For the final hallucination scene in the farmhouse editor James Vandewater and Cronenberg – who’s heavily involved in the editing – intercut between rephotographed and camera original material. “Anytime you rephotographed the material you must zoom in on the image a little because when the diopter moves, the frame elements surrounding it move in and out. You don’t want to see the square outside the frame, so you must zoom in. It’s like an editing strobe of zooming in and out which is quite experimental for a movie of this size,” the cinematographer adds.

Infinity Pool took 10 months to edit for a reason. The initial hallucination sequence alone of James in the doubling chamber took four weeks to cut. And two minutes of material contain over 350 edits, including stop motion crafted by UK stop motion artist Lee Hardcastle and special makeup effects artists Dan Martin from the UK and Traci Loader. No CGI features in the hallucination scenes, and elsewhere visual effects were only used for a blade extension in a stabbing sequence, or to erase shadows or erase kneepads when James is on the ground waiting to be executed.

As Possessor was a UK/Canada co-production and introduced Hussain and Cronenberg to many great collaborators and friends, they wanted a sizeable UK contingent making up the Infinity Pool crew. “But then a little technicality called Brexit came into play and because Infinity Pool is a Canada/Europe co-production, we couldn’t bring on our regular UK technicians. Some we insisted to work with like Dan Martin, but we would have liked more of our UK collaborators to join us.”

In line with Cronenberg’s desire for the film “to fill the television screen” – which Hussain highlights many people will watch the film on – they selected a 1.78:1 aspect ratio. “Shooting 1.78 means you can play headroom and short framing more, so characters are crushed by their environments from the weight of the negative space above. In scope, you’re always playing the sides, which is great for certain movies, but Brandon prefers the weight of the world to crush his characters. We also created a lot of mystery in the sides of frame.”

Lighting within the frame

Shooting in two locations required collaboration with Hungarian and Croatian crew. While some translation issues were encountered, Hussain found gaffers Slaven Spincic in Croatia and Attila Berta in Hungary and their lighting crew “to be excellent across the board.” The cinematographer and gaffers discovered an entire night sequence could be lit with just a handful of Astera Titan tubes on Long John Silver stands.

“Instead of using lifts, a large generator or putting up a big light, a few Asteras – set at 10,000K and shot at 4,000K on the camera – could be operated just off the battery. Most of the movie was shot at 4,000K colour temperature on the camera to create a slightly amber sickly feeling,” says Hussain. “When working with sources on tall stands in multiple locations you must watch out for the shadows, so you avoid showing the floor too much.”

The cinematographer aims to build the lighting within the frame to enable the team to move quickly on set. For the execution sequences he worked with barely dimmed PAR CANs above, and used Cinefade to find the correct level matching all lenses. All tungsten sequences were then also shot at 4,000K to create the same “off feeling” as the rest of the film. An 18K ARRI Max backlit windows in addition to atmosphere being used whenever possible.

Shooting beach sequences offered the advantage of a natural bounce from the sand. “But other sequences such as the final shot in the movie of Alexander Skarsgård on a beach in the rain, was shot in full sun. So, we surrounded him with 18K ARRI Maxes to brighten the hell out of him, matching him to the brightest point in the frame and then added an incredible amount of NDs,” says Hussain. “On the Cinefade I dialed it down so the sky started to become dark, and I could get definition on him. The rain was naturally backlit by the very bright ARRI Max 18Ks.”

An extreme canvas

Like Possessor and the short film preceding it, the filmmakers shot Infinity Pool on the ARRI Alexa Mini which they believe to be “the best camera for the techniques being explored”. To create a more filmic look, they shot 2K ProRes 4444 and blew it up to 4K in post.

“As Brandon doesn’t like diffusion, we used a very compressed file format to soften the image. The very sharp digital look does not excite us, and I don’t need to count every performer’s pore or nose hair,” says Hussain. “Combined with vintage lenses, a specific LUT, and shooting at 1280 ISO this equaled a filmic image, even in day exteriors. Cinefade also helped, particularly in changing sun conditions when I used it as a remotely controlled variable ND and intercut, usually between B camera on a zoom and A camera wide open on a prime.”

The simplistic LUT, created with DIT and dailies colourist Balázs Budai, produced a slightly desaturated look with softer contrast that was balanced depending on each lens’s colour temperature. “When a focal length was used with a slightly different colour to it, the LUT matching that lens was placed on it,” adds Hussain. “Jim Fleming at Company 3, the colorist who grades all our films, knows the look we’re going for. While still very in your face, this look is slightly more desaturated, less deep, and with less contrast than Possessor. We wanted to go even softer to make the resort feel more uneasy, dreamlike, and strange to illustrate that tourism is a strange fantasy.”

When creating the distinct look, working with the TLS rehoused Canon K35s was a joy as they are lenses Hussain and Cronenberg know well and “adore their chromatic aberration, bokeh and fall off”. Building upon testing for Possessor they also occasionally used Hussain’s “usual stock 90mm macro Kilar, some Helios 44-58mm lenses and the LAOWO macro probe. One newer lens we worked with was the LAOWO 12mm zero distortion lens. It’s rare for Brandon to use a lens that wide, but he surprised me.”

Hussain was impressed by the Hungarian crew including focus pullers Peter Krajnyak and Gergo Csepregi who shot wide open and Agnesh Pakozdi who shot a large amount of second unit, supervised by producer Andrew Cividino. “Many people behind the camera in Hungary are male and I wanted a woman shooting second unit. Agnesh left Hungary as she was able to get more work in Germany and is now a high-level cinematographer who kindly took on B camera second unit. This was one of the best second units I’ve worked with. When I see her shots, it’s as if I shot them.”

Camera movement was based instinctually on the performers’ movements and achieved through close partnership between Hussain and A camera operator and Steadicam operator Yoann Malnati, “Some shots were precisely captured on dolly to punctuate a scene, but mostly it’s freeform Steadicam moving with performers, sometimes in the circle surrounding them, particularly in the scene when James beats up his double,” says Hussain. “That’s then intercut with B camera operator Agnesh’s footage, who’d usually be long lens on the zoom capturing unusual details and shooting through reflections. A few slow and meticulous ‘70s-style zooms are also used to create a voyeuristic feeling.”

To produce the ever-increasing feeling of anxiety the camera was predominantly kept on Skarsgård, while other dialogue takes place off camera. Slow zooms to highlight his isolation were also utilised along with extreme close-ups at unexpected moments. “We completed entire dialogue sequences just with extreme close-ups of eyes and mouths which was fun. We like to see the very wide world and then the world within the world, the truth hidden in extreme close-ups,” says Hussain.

Sequences involving violence or gory detail were discussed with special makeup effects artist Dan Martin to determine the best technique. “For the crash sequence we didn’t show too much explicit detail of the facial damage, it’s more in shadow,” says Hussain. “Sometimes less is more, but frequently more is more in the Brandon Cronenberg world and we went for it. It’s a movie that’s supposed to be a slap to the face; it’s not supposed to be polite. But if you’re going to do it, do it well.”

The filming of orgy sequences on sound stage in Hungary was kept private, precisely discussed with the performers, and an intimacy coordinator was on set throughout. “Everybody worked in tandem so when executing scenes, it was rehearsed so meticulously it was like doing a ballet,” says Hussain. “There are some things in that scene human bodies just physically cannot do, so those are puppets.”

While Infinity Pool contains undeniably shocking elements, Hussain is not an advocate for filmmaking that relies on the extreme and disturbing without an idea behind it or “throwing blood around for no reason”. For him the film is “at its core a very political movie about many things. The sex and violence are not apart from the movie, they’re actually the narrative of it and reflect the content of the film. The story needed to play out on an extreme canvas because that is literally the narrative of the film, and I believe that level of extreme horror, when it’s there for a reason, makes for a very effective movie.”