Home » Features » Interviews » Visionary »

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JOHN DAVEY

The esteemed British cinematographer on his 50-year career and his most recent project with close collaborator Frederick Wiseman, as told to Madelyn Most.

“I remember one Friday morning in October 1966 at the student union in Cardiff, where I was in my second year at [medical] school, when news broke over the radio that volunteers were urgently needed to assist in a rescue effort after the collapse of a colliery spoil tip,” John Davey recalls. “We were a bunch of 19-year-olds, talking about which parties we would go to over the weekend, but on hearing the news we went straight off to help. We had no idea what we were going into.

“A period of heavy rain in this remote Welsh valley caused an avalanche of coal waste to slide down a mountain and engulf a primary school and a row of nearby houses. It was 9:15 in the morning when this occurred, but because of the rain and fog, many school buses were late arriving and only half the normal number of children were inside the building. I have a vivid memory of walking through the village and seeing torrents of black sludge cascading towards us, lots of coal miners and ordinary people of all ages with picks and shovels, and lines of traumatised parents all working desperately to find anyone trapped underneath.

“Once inside the collapsed school, we had to dig with our bare hands, there was no machinery. Silence was frequently called to listen for anyone who might still be alive. It was very difficult to extract the bodies and took several hours just to get even one child out. I remember the smell of coal, whiffs of smoke from buildings, and dirty black water everywhere. We all were wet and filthy but worked straight through for about 36 hours until sheer exhaustion made us stop. I think it was 116 children and 28 teachers who were buried alive underneath millions of tons of coal that day. Even now, 55 years later, I find it deeply upsetting remembering that day and I still choke up.

“I never again spoke about my experience at Aberfan.”

John Davey’s career as a cinematographer spans over 50 years and has brought him international recognition, including a win at the Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography. Born on a farm in the Cotswolds, he grew up in Cardiff, South Wales, and like many cinematographers, developed an interest in still photography at an early age. He wasn’t exposed to cinema or movie theatres, but at the library, discovered photography books by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Ansel Adams, or Robert Frank, and was drawn to the pictures of the American Depression and the Deep South. With these books he also taught himself how to process and print 35mm film negative. When his aunt bought him an unusual 35mm Japanese stills camera, he would wake up at the crack of dawn, cycle to the Rhondda Valley or the Cardiff docks in Tiger Bay and take photos in the early morning mists.

“When I look back at my old black and white negatives, I realise I did develop a kind of documentary style even though I had no idea what I was doing,” he says.

Davey studied anatomy, botany, and physiology, and drifted into medical school in Cardiff, but later on decided it wasn’t for him. He says he needed to get away from South Wales and pursue his interest in photography. Growing up in Wales and playing rugby was an important part of his life; he joined the London Welsh Rugby Club, and later, the Askeans Rugby Club but travelling abroad for work and having a family “put paid to my very unrealistic dream of playing for the British and Irish Lions,” he adds.

A flair for film

Exactly four weeks after the Aberfan disaster, Davey moved to London and started working as a trainee assistant making films with the National Coal Board (NCB) film unit despite never having seen a movie camera before. “The NCB film unit was a great place to learn; we travelled to coal fields all over the UK making training and safety films, plus Mining Review, that were short films, similar to Pathé News, that were shown before the main feature in over 700 cinemas and watched by 12 million people, mostly in the mining communities. We often worked underground on a coal face, with 35mm Newman Sinclair clockwork cameras and 200-foot magazines. I felt like I was in Hollywood!”

… A month after your traumatic experience at Aberfan, you accepted a job filming underground in coal mines?

“Yeah, that was weird.”

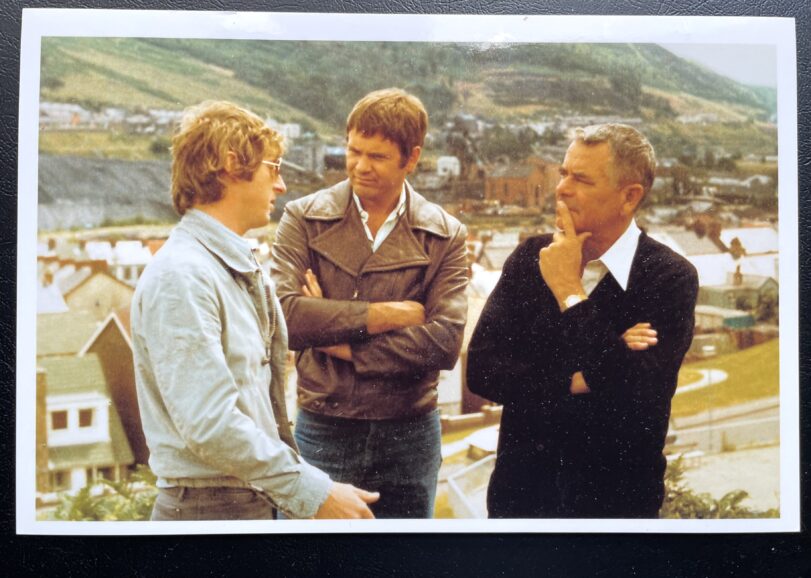

12 years later, purely by chance, Davey returned to Aberfan to photograph a TV documentary series called When Havoc Struck, hosted by Glenn Ford.

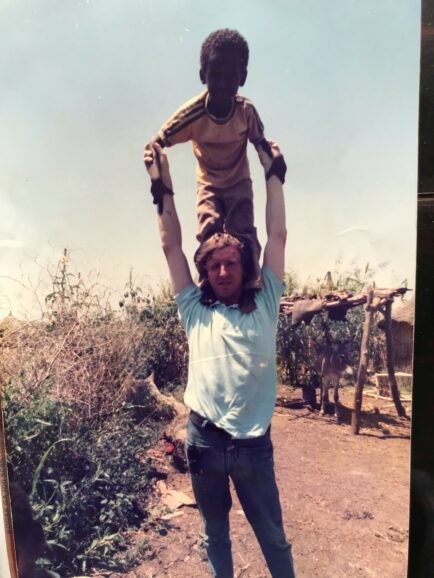

“After I got my ACTT union ticket at the NCB, I worked freelance in both film and television for NGOs in refugee camps in Sudan, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, for the International Red Cross, as well as current affairs documentaries in hostile environments for Granada’s World in Action, Thames TV’s This Week and London Weekend. I was fortunate to work as assistant camera to renown cameramen like George Jesse Turner and Bill Brayne. Frequently we would go to Northern Ireland to do in-depth documentaries with ‘the Hard Men’. We filmed the IRA, the Republicans, the Protestant Nationalists, the British Army, the prison service, the Northern Ireland police. The day after Bloody Sunday, Bill Brayne and I were shooting a World in Action and could still see blood in the gutters of those who had been shot the previous day, and shrines set up in the streets of Derry”.

Were there any threats to your life?

“No.”

Both This Week and World in Action were highly regarded news/reportage programs without an obvious political bias, they drew a large TV audience in the 70s. WIA programmes were extremely well researched, and they often had ‘good contacts’ inside the groups they were filming, some of whom wanted the publicity. “I do remember during a Protestant rally, Ian Paisley spotted me and there was a kind of a veiled threat, like ‘We know who you are and you’re not on our side.’ When filming the National Front in Leicester for This Week, I did feel nervous at times as bricks and bottles went flying past my head. In Cyprus, with Jonathan Dimbleby, we were shelled and came under machine gun fire by the invading Turkish forces. When we filmed The Official War Artist in the Balkans for the BBC, we came under sniper fire on a few occasions from the Croatian Army. I never was a war junkie; it was just the type of non-fiction work I was doing.

“I was also shooting pop promos, commercials with directors like Terence Donovan, some Play For Today TV dramas. Sometimes I would do additional camera, or 2nd unit work for cinematographers like Chris Menges BSC and Clive Tickner BSC, working with directors like Stephen Frears, Michael Apted, and Ken Loach.”

Davey became involved with Allan King Associates (AKA), London’s largest independent documentary, film, and TV company created in 1961 by the Canadian Allan King, with fellow Canadian cinematographers Richard Leiterman CSC and Bill Brayne. “They also produced lots of music films and provided crews for “The Stones in the Park” and the Isle of Wight Festival,” he says. “Allan King famously borrowed a camera from Albert Maysles, and with Richard Leiterman, Bill Brayne, and sound recordist Christian Wangler, had made Warrendale in 1967, a feature length film that won the Prix d’Art in Cannes, and that shared the BAFTA that year for Best Foreign Film with [Michelangelo] Antonioni’s Blowup.”

AKA’s offices at 8-12 Broadwick Steet became a hub for freelance technicians and independent filmmakers to meet up where everyone was welcome. On the ground floor was Sammy’s RENTACAMERA and above AKA was Document Films, founded by cinematographers Charles Stewart, Ivan Strasburg BSC and Ernie Vincze BSC HSC. Solus Films, run by Jack Hazan and Mike Whitaker with young cameramen Dick Pope BSC and Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC, was around the corner in Marshall Street. There were talented filmmakers like Diane Tammes, Joan Churchill from the US, and Nick Broomfield, who had recently graduated from Beaconsfield’s National Film and Television School.

“We all collaborated on each other’s projects, multi-camera shoots, and music concerts,” Davey remembers. “You might run into John Lennon and Yoko Ono editing their film in a cutting room that Nic Knowland [BSC, of Tattooist] had shot, with Ivan Sharrock, sound recordist, and editor Richard Key. Allen Ginsberg was spotted there, while Jonathan Miller, Kenneth Anger, and Derek Jarman worked in other editing suites.

“Or, you could also run into Horace Ové, famous for his film about James Baldwin and Dick Gregory and especially for Pressure, the first ever Black feature film made in the UK. Once banned, now knighted, Sir Horace Ové is considered ‘the godfather of black British filmmaking’.” (The Trinidad and Tobago-born British filmmaker, photographer, painter and writer holds the Guinness World Record for being the first black British filmmaker to direct a feature-length film, Pressure (1976).)

“Yes, I remember that well… Pressure was my first job as camera assistant with cinematographer Michael Davis,” adds Most.

“Nic Knowland was collaborating with Jean-Pierre Beauviala on the design and development of the new 16mm Aaton camera. This wonderful new French camera was silent and balanced perfectly on your shoulder for handheld work. I.C.E. Co. was Aaton’s sales and distribution company tucked into a back corner at AKA headquarters with Peter Bryant in charge. In the mid-1970s, AKA associates included Bill Brayne, Christian Wangler, Peter Moseley, Mike Dodds, Ivan Sharrock, Iain Bruce, Mike Davis (father of Ben), Bruce White, David John, Alan Jones, Richard Key, Clive Tickner [BSC] and accountant Stephen Mellor, and former associates were Chris Menges [BSC], Roger Graef, and Roland Joffé.”

Breakout work

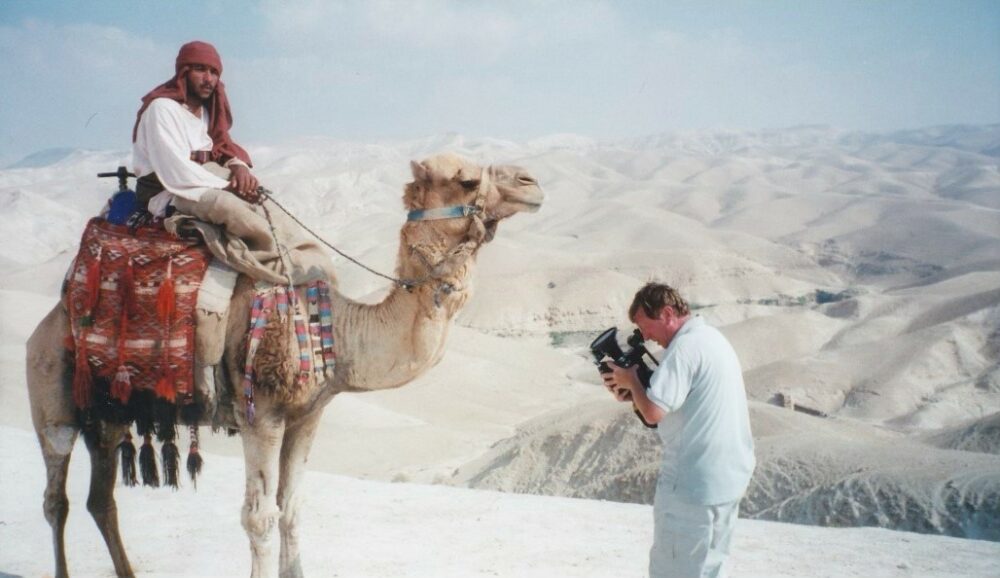

“One of my big breaks was being asked to shoot an anthropology documentary for Granada TV’s Disappearing World series, called The Kirghiz of Afghanistan,” says Davey. “We travelled 16,000 feet in the foothills of the Himalayas to film these pastoral nomads. In those days, before leaving for two, three, even five months to these remote inaccessible places, you’d test the camera and filmstock, and then set off with a crew of two on camera, one on sound, a director, researcher, anthropologist, a 16mm Éclair NPR camera, 60 rolls of film negative, and a Honda generator to charge batteries. When you returned to London, you sent the film off to Humphries Laboratories and only then, did you see what you shot. That’s just how it was.

“Mike Dodds went down the Amazon, Chris Menges went off to Burma and didn’t return for a year, Stephen Goldblatt [BSC ASC], Ian Bruce and Carlos Pasini went to Brazil, Mike Davis was in Laos, then in Vietnam during the war with Mike Beckham, and André Singer, Brian Moser, or Chris Curling were shooting tribal life in remote corners of Africa, Asia or South America. Our tiny office screening room was always packed with people cramming to see our rushes when we returned.”

“Taking pictures was always a passion that I had. For me the best job on a film crew has always been operating a camera. I adore operating, I love the challenges. Capturing images that you hope and pray people will enjoy looking at gives me great satisfaction. It gives a feeling of joy looking through the viewfinder. I’ve been so lucky.”

John Davey

How did you start working with Fred Wiseman?

For the uninitiated, Frederick Wiseman is the iconic, prolific award-winning American theatre and film director, author of more than 45 documentaries that primarily explore American institutions without any commentary. Although he is a few months away from 93, he continues to make films almost back-to-back, that he edits in his Paris cutting room.

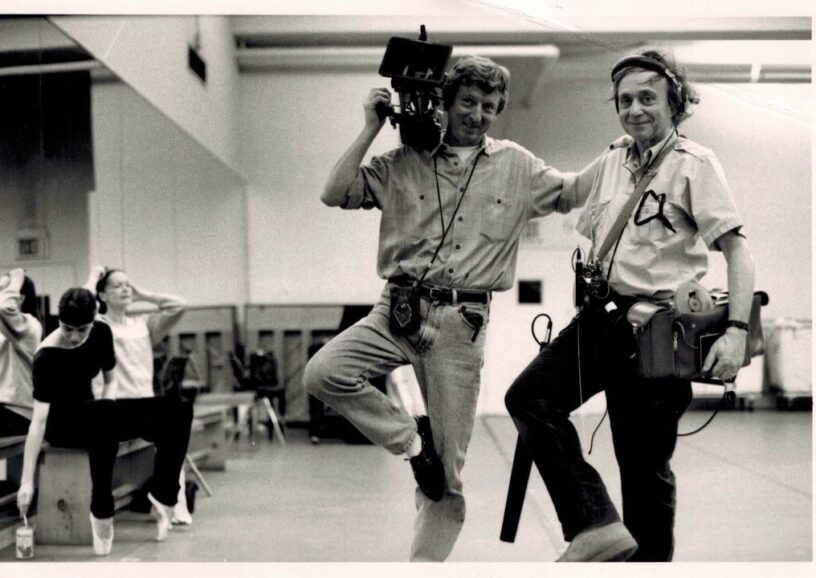

”At AKA, Bill Brayne had been shooting Fred Wiseman’s films for about 10 years. He took over from Richard Leiterman who photographed High School and before that, it was John Marshall who photographed Titicut Follies, which was the very first film Fred ever made after giving up teaching law in Boston. Fred just picked up a Nagra after getting a few lessons in sound recording from the Maysles brothers. When Bill Brayne transitioned to directing, he recommended me to Fred.

“The first film we did together was Manoeuvre in 1978, following a tank platoon from Louisiana to West Germany for war games, that we shot in B&W on a 16mm Éclair NPR camera. Since then, I’ve photographed about 33 films for Fred over a period of 44 years: 27 in the US, including nine in New York; one in London, and four in France. I’ve shot about six million feet of 16mm B&W, and colour film, and about 1,500-2,000 hours of digital since La Danse in 2008, the documentary about the Paris Opéra Garnier, the last film we made on celluloid. “With Fred, he will decide on a particular sequence to shoot, but once we start filming, he is absorbed in recording sound. From experience I know how he wants me to shoot it, so I’ll have complete freedom on composition, hand-held or tripod, whatever I feel will give him the footage he wants to see once he’s in his cutting room. It’s a cinematographer’s dream to be given such freedom. Also, I choose which camera to use, what angle to shoot from, and what to cover. 99% of the time, I choose the lights and where to put them; I set them up myself if we don’t have a gaffer. That’s the great thing about working with Fred – he encourages me to do my own thing. When Fred is recording sound, he’s in his own world listening to conversations and always recording unusual wild tracks, but although we rarely talk whilst we’re shooting, sometimes we make the occasional eye contact. We’ve developed quite a large vocabulary of visual ‘looks’ and we always know what messages we are sending each other.”

Working with Wiseman

Fred Wiseman’s films distinctively have no interviews, no narration, and no commentary. He leaves everything up to the audience to observe, absorb, and understand on their own.

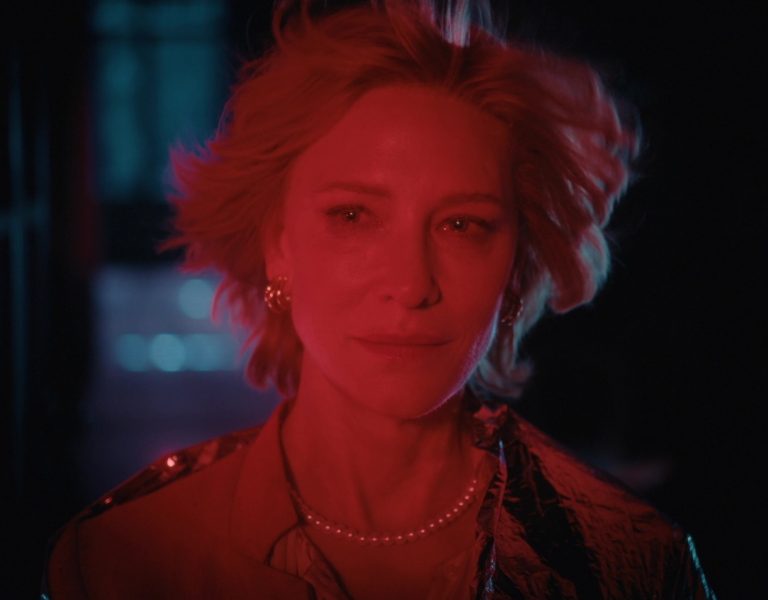

“I am always quietly picking up shots on the fly and cut-aways, especially on our latest collaboration, A Couple, one of Fred’s rare forays into fiction,” Davey adds. It is a French film that screened ‘In Competition’ at the Venice Film Festival in September and the New York Film Festival in October.

The 63-minute drama is based on The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy that reveals very personal details of her 57 years of marital life with the aristocrat, Count Leo Tolstoy, considered to be one of the greatest writers of the 19th century and Russia’s greatest writer of all time, whom she married one week after meeting him when she was 18 years old. Sofia Tolstoy was in her own right an accomplished writer, a multi-talented, intellectual woman, and a pioneer photographer in Russia in the late 1800s, who also bore her husband 13 children. The film is a monologue where Sophia reflects on her unhappy, turbulent circumstances living under the shadow of the great man.

French actor Nathalie Boutefeu, who plays Sophia and co-wrote the screenplay with Fred Wiseman, says: “The idea for the project came from the thousands of hours of conversations that Fred and I have had about art and the life of a couple (marital life), love, the sharing of liberty, territory/space, and the act of creation…”

This project was in gestation for a long time, Davey explains. “In 2020, when we were in Boston shooting City Hall, Fred asked me if it was possible to shoot a feature film with a documentary crew, and initially I laughed. When he asked me to shoot the film, I originally turned it down for several reasons. Firstly, during the height of the pandemic, nobody was allowed to travel outside the UK. Brexit prevented me from working in France, and [I] probably would need a work visa, and carnets to travel abroad with camera equipment from Aimimage in London are always complicated. Most importantly, I hadn’t fully recovered from COVID myself… but Fred was very persuasive and found a fantastic French crew that spoke perfect English, so I agreed.

“There was no time for a recce or a scout. Fred sometimes raises the finances for his films, but the budgets are modest. He said we’d be shooting the entire film outside, day exteriors, in a friend’s garden on the island of Belle‑île, off the coast of Brittany. We’d shoot in May when the flowers are in full bloom with vibrant colours. Fred sent me pictures from his iPhone, but when I arrived, this ‘garden’ was vast; about 150 hectares with forests, woodlands, hills, pastures, grasslands, lakes, and ponds.”

Everyone is familiar with the pointed rocks and craggy coastline in Monet’s famous paintings of Belle‑île. “Ivan Sharrock warned me about the blustery winds coming off the Atlantic so I knew there would be technical challenges facing us all,” Davey adds.

“Maybe the smallest crew in the history of feature films, ours consisted of Fred, the director, Nathalie the co-writer and actor, Jean-Paul Mugel, the sound recordist, Andra Tevy, a fantastic 1st camera assistant, Chantal Pernecker, our script supervisor, Alice Henne, the DIT, who doubled as a second assistant, and my colleague Jane-Marie Franklyn who volunteered as an all-round production assistant. It was the breeding season for frogs, and they made an almighty racket so when we shot by the lake, one of her jobs, besides helping me, Andra, Nathalie and Fred, was throwing stones to get them to shut up.

“We shot 35 sequences in 17 days! That is working very fast, considering the weather and the lighting conditions were constantly changing. Most days might start off with sun and blue skies, then clouds would come over and it could start raining…so that’s challenging for maintaining lighting continuity. Fred had a little radio video link monitor around his neck, but it’s difficult to really see images clearly or pick up the details when the skies are so bright. There was no time beforehand to do tests for hair/makeup/costumes: we went straight into shooting. For Fred’s films, I usually shoot in 1.85, but my friend Dick Pope suggested the 2.39 widescreen format and using the negative space to emphasize the loneliness and isolation of the character. Fred liked the idea and said, ‘That’s exactly what the film is about.’”

The cinematographer’s toolkit

Davey shares more about his kit: “I took all the usual things: ND grads, hard and soft edge filters, but it was an uneven, staggered horizon, so there was always the risk that the sky could burn out. I chose the ARRI Amira for its incredible dynamic range of about 14 stops, and a few Optimo zooms, and a set of Cooke Prime lenses. The ARRI Amira copes better than some other digital cameras and it is also quite rugged. My priority was to pay attention to the exposure and not let the sky burn out too much. If there were clouds in the sky, it’s possible to bracket and bring up details in the DI and pull back details of clouds.

“I know Fred prefers static shots, he doesn’t like to have pans, zooms, tilts or ‘nothing fancy’ – he wants minimal camera movement. I would have loved to do some subtle tracking shots, but it would have been impossible because of the terrain and we would have needed more crew.”

For Un Couple, Wiseman opted to shoot each scene in three sizes. “First, in a wide master shot, then in a medium, and then a close-up,” Davey says. “If Nathalie was walking through the woods, or standing at the edge of a cliff, or sitting in a field, we would shoot it two or three separate times, slightly changing frame size or camera position. Fred likes to have choices and to make the editorial decisions in the cutting room and not on set; he wants to study the performance and how the lines were delivered. For me, this sometimes presented a challenge. I’d shoot the master in sunlight, and once we’d get that done, things might change depending on the weather with lots of strong winds with cloud formations accumulating. In harsh light with the sun directly overhead, you see all those horrible shadows under the nose or chin. On the wide shots, there wasn’t really much I could do, but on the medium, or close-ups, I used a small silk to diffuse and soften the strong sunlight. Sharp eyes will pick out the bright light in the wide shot but notice a difference when we cut to a medium or close-up. When I explain my concerns to Fred, he replies, ‘Well, Gilles can do his magic.’”

The grade was undertaken by colourist Gilles Granier at Le Labo in Paris. “Gilles has been grading our films for the last 10 years. He uses Lightworks software, and he is really good at fixing these situations in the final grade. Before we started shooting, Gilles put together a setting of LUTs that we literally programmed into the camera three-four hours before we started shooting, and I think it worked very well. Giles asked me not to fiddle with the iris when the sun is going in and out during shots. He says it’s better to just leave it and he’ll sort it out afterward in post. When you think something is burning out, the Amira’s incredible dynamic range can cope with details tucked away. Gilles was also able to paint out a tiny figure in the far distance walking on the beach, and on the cliffs that I didn’t spot at the time. A DI cannot cure bad cinematography, but you can do an enormous amount to improve the image in post.”

Granier has worked on around eight of Wiseman and Davey’s previous films, so the trio enjoy a good working relationship. “Gilles is very used to dealing with me and Fred [and] he knows there will be a lot of back-and-forth banter between us about the image and ‘the look’ of the film,” says Davey. “Fred likes images that are bright, colourful, detailed, sharp, with less contrast. He likes to see some details of faces in the shadows. I’m usually happy to let it go but I think this can be a problem with the technology that’s now available. He wants me to shoot it straight, it’s always 24 fps and he doesn’t want ‘the distraction of fiddling around’. He has rigidly stuck to that philosophy for 44 years. I usually prefer a darker, more contrasty, de-saturated image that is a bit moody and textured. Eventually, we work something out, but, after all, he’s the director, it’s his show, so I go along with it.”

Wrapping up

Towards the end of the schedule, Wiseman agreed to do some interiors. “In fact, the very last sequence of the film is a night interior in the attic of a barn where Sophia is writing letters in her diary that is lit by double-wick candles and another sequence lit with my grandmother’s old oil lamp that I brought out from England,” Davey recalls. “I used these and a panel light as a very soft fill, just out of frame with half straw and black wrap around the edges so that light didn’t spill on the background. Panel lights were also handy when the light dropped off in late afternoon/early evening and we had to complete the scene. These small lights run on batteries or on mains, tungsten or daylight, which allowed me to give the image, and specifically her face, a little lift.

“We also did the DI in record time. The film is one hour and three minutes and we did the entire DI over a weekend, which is pretty amazing. The results are okay, it’s not brilliant. There are a few nice shots in the film, but I don’t think I’ve ever been satisfied with anything I’ve shot.”

Davey shares more about his collaborative approach with Wiseman. “With Fred, you’ve got to be ready to turn over at any time. He wanted me to pick up shots of Nathalie when she was just thinking about the next sequence, contemplating, walking around rehearsing her lines. There are never enough cutaways for Fred and in this film, he wanted to capture ‘the biological world’. Having photographed so many nature and wildlife films for the BBC, National Geographic, or Discovery, I grabbed lots of close-ups of birds, frogs, flowers, plants, ants and insects. Both Fred and I love abstract shots, so I shot things like silhouettes of trees swaying in the wind, shadows, reflections on the water, clouds passing over, waves crashing. The idea was to emphasize the contrast, the harshness, animals trying to survive, the rocks, the rough terrain. Nathalie was very brave, having to act and deliver her lines while walking along the cliff edge where a meter to her right or left might be a drop of several hundred feet.”

Davey says that Wiseman always wants to have plenty of choices in the edit and likes him to shoot a lot of footage, but he only uses about three percent of what they shoot. Over the course of two or three months, that can amount to 150 hours of material that is edited down to a three-hour documentary. He says it can be a bit frustrating knowing 97% of what you’ve shot ends up on the cutting room floor and when you have photographed so many beautiful shots that never appear in the film.

“When we shoot on film, and the light drops off, I’ll show Fred the needle of my light meter that is barely moving and explain that the image will be dark, grainy, flat, barely visible… and he says, ‘If it’s no good, I won’t use it, but why don’t you shoot it anyway?’

“Film is forgiving, there is usually some kind of an image, so in the end, those sequences often end up in the final cut. When I mention to Fred that my colleagues will think I am a lousy cinematographer, he says….’Well, no one has ever complained to me.’”

Eh oui, many would say these two too are “A Couple”.

Words: Madelyn Most