Home » Features » Opinion » Letter From America »

“Times have changed, and rapidly,” wrote Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Will Bunch, speaking about a wave of labour unrest that seems poised to sweep over America this fall and winter. He wrote of certain companies posting record profits even “during the depths of the pandemic in 2020,” with workers “leaned on to give up their weekends or to work grueling 12-hour shifts — making extra cash but losing time with their family and utterly exhausted when they did finally make it home.”

Was he talking about studios, scrambling to make more “content” for stream-hungry viewers busily and blearily binging during lockdown? No, he was actually talking about breakfast cereals and microwaveable snacks.

One “tell” that he wasn’t talking about showbiz: The shifts in question would’ve been much longer than 12 hours.

Bunch was writing about a walkout at the Kellogg’s plant in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where workers in the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union found themselves “stunned” when, after the current contract expired, management wanted givebacks on vacations and pensions, while creating a lower-wage tiered system for newer hires.

This despite the company’s aforementioned record profits, a stock buyback, and the CEO’s $11.6 million payday in 2020, which may even be on the low end these days of what constitutes a “living wage” in executive suites.

That same Bakery union is part of the AFL-CIO, the umbrella American labour organisation that also includes IATSE, and all its various locals, grips gaffers, camera folk, editors, and the rest – whether actually located here in Hollywood, or on the stages and lots of Atlanta, Albuquerque, and anywhere else there’s a union crew shooting a studio project.

Bunch was putting the food workers’ strike in the context of “planned work stoppages — from other traditional factories to hospitals, college campuses, and even Hollywood — (which) could number tens of thousands before autumn is done.”

“Even Hollywood,” indeed. And so far, the stoppages are showing no signs of stopping. As we were writing this, workers for agricultural equipment manufacturer John Deere also voted overwhelmingly to strike – just as IATSE did last month – saying, like their Kellogg’s counterparts, that future workers would be sacrificed for current gains, and pointing to the disparity in what CEOs pocket, vs. frontline workers. Subsequently, they’ve walked out, unlike IATSE, which – during the course of this article being written, and being laid out – came to a tentative deal with the producers, represented by the AMPTP.

The tentative settlement averts what would have been the union’s first-ever walkout in Hollywood history. And if you’re wondering about that “first ever,” as mentioned in our recent web column, the last time below the line film workers did walk , not only was there no television, but it was a different group of unions – the now defunct Conference of Studio Unions – which staged the walkout.

Which a then-fairly corrupt, and studio-friendly IA was opposed to. But the times, as Mr. Bunch (and Mr. Dylan before him) noted, are a-changin’.

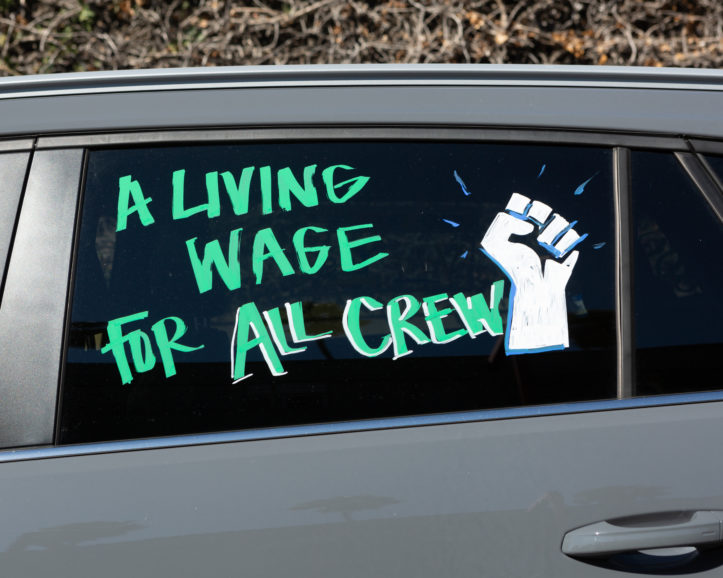

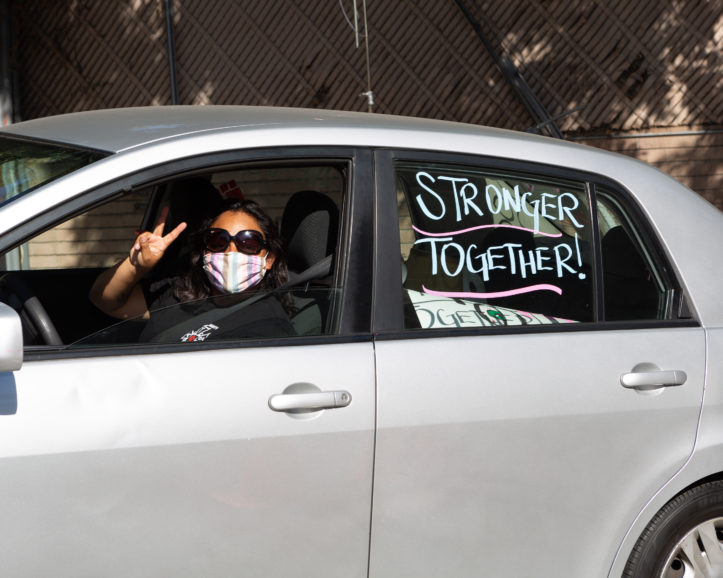

Some may be changes – beyond the obvious statistical ones – wrought by our recent plague year. When we attended a “Drive-thru” event held by IA Locals 600 and 700 – cinematographers and editors – on the eve of the strike vote announcement, 600’s Executive Director Rebecca Rhine talked about “things we learned, coming out of the pandemic,” including the realisation that people were not willing to sacrifice anything, at any cost, to simply hold on to work. The slower rhythms – and this may be why those who structure things in society usually choose against “slower rhythms” – gave people an unexpected stretch of time to consider these aspects of their life, and a sobering backdrop against which to do it.

This reconsideration is happening everywhere. Washington Post columnist Karla Miller wrote about the “Great Walkaway,” another kind of worker resistance – usually outside of unions – where people are simply quitting jobs, and getting other ones, when the conditions become too abusive or excessive, noting there’s been “a long-simmering but barely tolerable state of discontent in which the pandemic abruptly cranked up the heat, making the situation ‘jump or boil.’”

As we quoted Rhine in that same web column, this is “much bigger than the entertainment industry,” as she drew lines between Amazon workers in a warehouse, or on sets, or conversely, Apple employees on an assembly line, versus a soundstage. “This is the fight,” she said, “and this is the moment.”

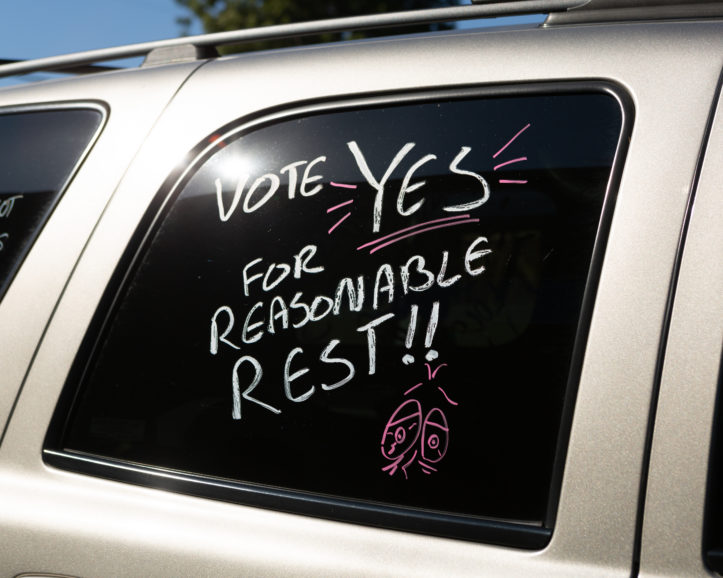

A moment that, if it is indeed resolved with a new contract that speaks to the IATSE’s current demands (actual meal breaks instead of meal penalties, longer rest between calls, and shifts that won’t have exhausted workers rolling their cars on the way home, among other things), will continue to have resonance.

Though it’s interesting to note that many IA workers swiftly took to online posts to decry the proposed settlement as too little, particularly in terms of turnaround times (10 hours), weekends (54 hours, approximating what SAG already has, but eliminating at least one full night of sleep), and more. With a ratification vote some weeks away as of this writing, it will be interesting to see if rank-and-file pushback grows.

From a Hollywood perspective, there will also be some precedent set when the DGA contract expires a year or so down the line (including whether “new” media should continue to be treated differently – or do we mean deferentially? – by workers).

And while many showbiz workers have skills they’ve spent lifetimes honing, behind lenses, rendering sets, designing lights, composing music, etc., with an artistry that can’t just be plunked down somewhere else (or is easily replaced), this isn’t merely a spat between Hollywood workers often thought immune to recessions, and ownership.

What’s happening here isn’t necessarily “exceptional,” the way showbiz often likes to think of itself, but part of a larger story. Miller quoted a financial worker in her column, saying “for no money in the world would I go back to my pre-COVID life.”

Evidently, none of us will be. But much is in the balance as we wait and see how that story – in which we’re all participants, including, now, the professional story-makers – continues to unfold.

Comment / Laurence Johnson, sustainability manager, Film London