And happy new year to you too, dear reader!

We pick up kinda where we left off with 2021: Pandemic surges, already-tenuous societal lattice-work on both sides of the Atlantic increasingly rattled, and the surreal becoming more steadily commonplace.

In that spirit then, we open this year’s column with a kind of meta reflection on cinematography itself, as contained in the recent Netflix series Voir.

Continentally savvy readers already know “voir” means “to see,” but this is a series about “seeing” movies, cinema, in the broadest sense, which is to say, what films mean, and what effect they have on both individuals, and the world at large. It’s done in a series of visual meditations, usually on the specific film in question which sent the various narrators into their respective futures as essayists, bloggers, reviewers, and makers of the medium.

From producers David Fincher and David Prior, Voir dropped with vastly less fanfare accorded to something like a new Cobra Kai or Witcher season, perhaps because it’s non-fiction, or more likely, because each episode averages about fifteen minutes.

They are shorts in other words. About movies. You can watch one in the run-up to seeing The Power of the Dog.

We caught up with cinematographer Martim Vian, who shot four of the series’ six episodes. The one we wanted to really talk to him about though, was the first one (if simultaneously dropped episodes can be said to have an order), called Summer of the Shark.

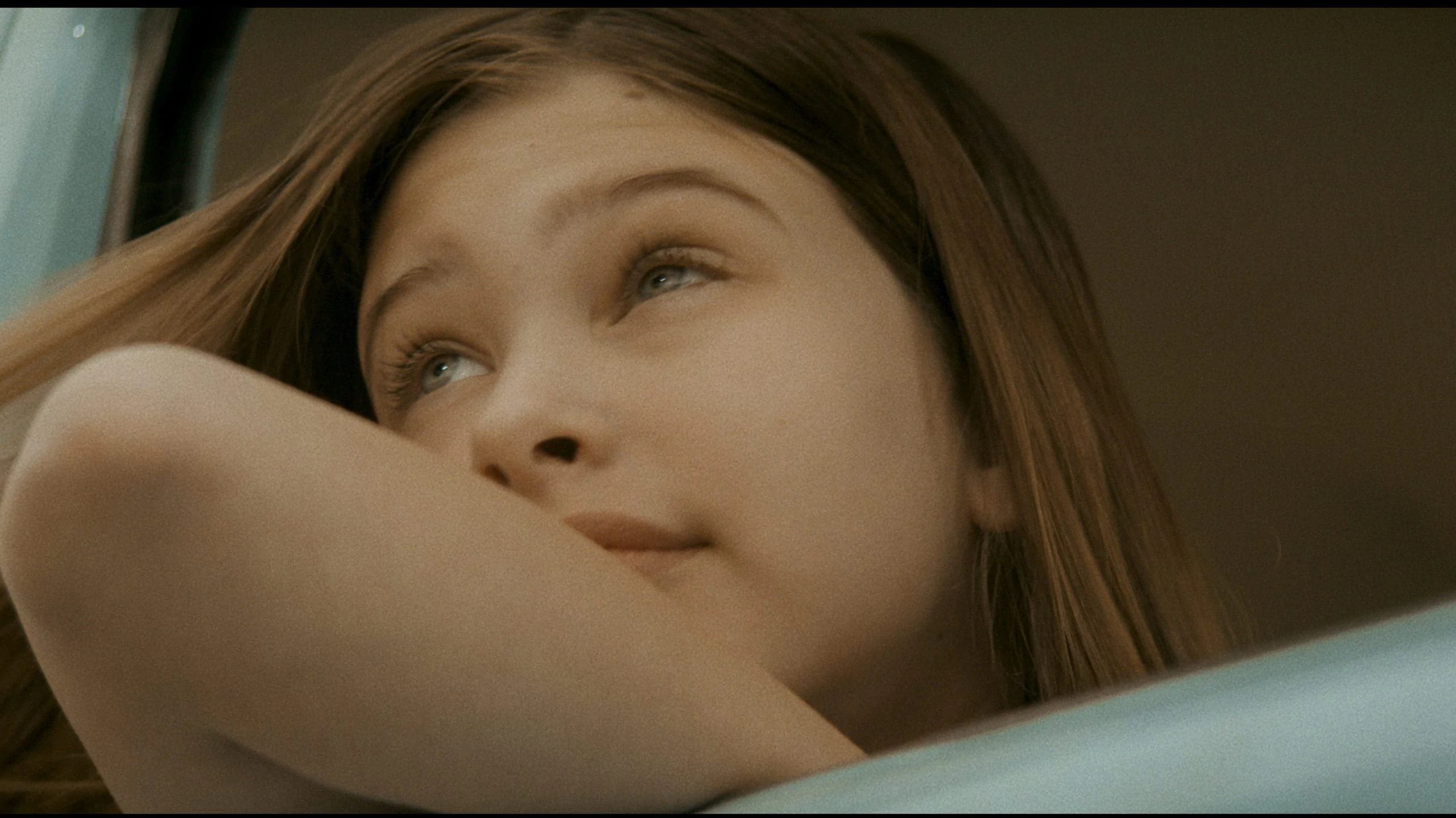

Kind of like a compressed Licorice Pizza, it’s the story of how film blogger Sasha Stone spent that pivotal Jaws summer watching Spielberg’s breakthrough blockbuster over and over in the theatre, with her big sister. Often, the two of them would be there for hours at a time, watching repeatedly – left by a somewhat overwhelmed single mom, who’d take them down from the countercultural redoubts of Topanga Canyon (just a few miles from where this is being written), into the San Fernando Valley floor, to one of the many no-longer-extant multiplexes (to say nothing of single screens!) that used to dot the area.

That, or Stone and her sister would head down from the hills to the west, winding up untended for long stretches at the beach, left on their own to speculate about sharks and other eruptions from the id.

One thing unique about this particular episode is that it has the most recreated history, and character movement, of the instalments, most of which tend to be, as Vian notes, “archival.”

Here, though, “Stone’s (story) was a lot more personal (and) also has an homage to that one movie.” Working with Prior, who was directing, “one of the things we decided to explore was using lenses from the period.”

So, sensibly enough, they contacted Panavision, where Bill Butler ASC’s glass had come from originally. They came away with “a set of C’s and some B’s (and) anamorphics as well.” But then “they found two zooms in a closet somewhere that, according to their records, had been in Jaws.”

This original lens was used to help recreate “the famous ‘Vertigo Zoom’ of Jaws.”

Yet despite its callbacks to the era, “we still wanted the episode to feel relatively current.” Hence, all that vintage zooming glass was connected to one of the two DXL2s they used, also from Panavision, while using the film emulation LUT, which comes in-camera. And though they “shifted things a tiny bit” for the DI, “we mostly kept things looking the way did on set.”

He credits this to the production design and finding locations that still retain a kind of ‘70s sheen, which the short film successfully captures. “I tried to light most of it with colours and lights that would make sense for the period,” and given that this correspondent also spent that particular summer in California going to a lot of movies – including the one about the shark – the veracity is commendable. Check it, and its companions out, when you’re looking for short subjects to round out the evening’s viewing.

Also successfully adapting to, if not to a change in era, certainly a change in locale, was Netflix’s The Lost Daughter for debut director Maggie Gyllenhaal, with Olivia Colman as a professor intending to take a summer idyll by the beach and get some historical and literary research done. Yet, it’s her own history, and her own stories, that have followed her there, threatening to usurp her entirely.

Gyllenhaal had seen some films shot by Hélène Louvart AFC, and thought she’d be a fit to help her adapt Elena Ferrante’s novel, originally written in Italian, and set in the author’s native country.

Louvart liked Gyllenhaal’s script, then met the director “once in London (for a) very short 45 minutes. (But) it was clear we could work together – she told me it was the same feeling.”

Meetings continued over Skype, but for a long time “we didn’t know where we could shoot,” because of the tenacious pandemic. “In the beginning we were going to shoot in New Jersey,” for the English-language adaptation, but “because of the COVID, we landed in Greece.”

So, the English screen version of the Italian novel was now set on a Greek isle, which seemed like a safer bet during production, though Louvart notes that though they “prepped five weeks on location, two weeks we continued to prep remotely,” because of the virus.

That also forced a change in how they worked, splitting the crew, with about half prepping ahead – including a local gaffer she’d worked with before – while the first group did the shooting.

Although Gyllenhaal had originally responded to work Louvart had shot on film, here they wound up working digitally. “We thought of shooting in Super 16mm,” she says, “but then when we arrived, we understood it would be easier to shoot in digital,”

They wound up using Cooke S4s with an Alexa Mini. “I like the combination,” she says, and “the Cookes are soft for the skin tone.”

This was important because Gyllenhaal had a penchant for working with close-ups: “I think it’s what she wanted to get, to be with them. It’s also Maggie’s point of view – if someone’s acting well in front of her, she comes closer to see. When the characters are good, why not be close?”

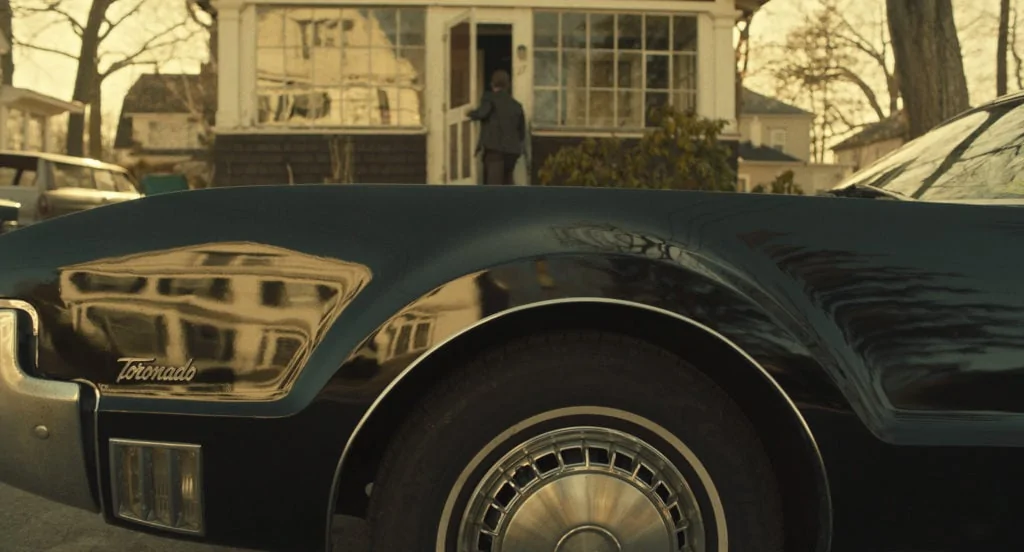

Another actor-turned-director who likes working on similarly intimate terms is George Clooney, especially if his recent Amazon film The Tender Bar is anything to go by. An adaptation of J.R. Moehringer’s book about growing up fatherless in ‘60s and ‘70s-era Long Island, it’s the story of seeking out surrogate role models in the house of extended relatives where his mother retreats, and at the local bar his Uncle Charlie, played by Ben Affleck, tends. Named “The Dickens,” it would seem to portend the literary path that lay ahead for Moehringer, who is played at different ages by Daniel Ranieri and Tye Sheridan.

In adapting the tale, Clooney brought along a familiar collaborator in Martin Ruhe ASC, who’s been working steadily with the actor-turned-helmer since Catch-22. Indeed, around the time this column appears, they should theoretically be prepping their next project, the ‘30s-era rowing drama The Boys in the Boat, in London. That is, if Omicron hasn’t upended those plans.

The two met when Clooney was shooting the Europe-set, ennui-laden thriller The American, directed by Anton Corbijn. As for Clooney’s switch to the director’s chair, Ruhe calls his approach “pretty straightforward,” coming to new projects with “some shots, some plans in mind.” Ruhe starts fleshing those out “from the feeling, from our conversations – I know he’s going to like to move fast. He’s not shy (about) making decisions. He’s also very visual,” and will include “some key frames, or key moments he has for the story… and that informs me pretty well for the rest.”

As for shooting a period piece, this one had them studying “films from the ‘70s, like Hal Ashby films (and) Dog Day Afternoon.” They also looked at the photographs of Willam Eggleston, whose own documentation of American life in the ‘70s was simultaneously hyperbolic and unflinching, using, in the words of the UK’s Independent, “heightened colour; in fact, his colours can be shrill to the point of near hysteria.”

Ruhe’s palette here, in conjunction with the work of production designer Kalina Ivanov, who also had a lot of Eggleston photos in the look book she’d prepared, couldn’t be called “hysterical” by any means, but everything, from the fraying interior of the working-class home where generations of J.R.’s family take refuge, definitely feels lived in. “It’s a blue-collar environment, it had seen its best time in the ‘40s or ‘50s,” Ruhe says. “It was looking good at some stage; when Pa dresses up, you see that (was) the time he was in good shape,” referring to a scene where Christopher Lloyd, as Grandpa, dons an old suit to take J.R. to a school “dads” event, in place of his perpetually missing father.

And while those particular interiors were all on stage, exteriors were in Boston, doubling for Long Island, a location switch prompted by earlier rounds of COVID, even though “parts of Boston were still in lockdown.”

For capturing this doubly-recreated past, Ruhe used Angenieux Optimo Zooms – “the compact ones” – along with “one long Optimo,” and some Cooke S4 glass,” also affixed to an Alexa Mini, and then the search was on “to find practical lighting,” such as the ‘80s-era fluorescents in a train station, when a now-grown J.R. commutes back and forth to college.

This joined other fluorescents along the way, like in an empty office building converted to look like the NY Times, where Moehringer begins his writing career, though in this case, by correcting copy, as opposed to writing it.

Otherwise, for a lot of the practicals, there were LEDs, which Ruhe found both more “subtle,” and better for speed, particularly some DMG Lumieres, which he describes as having “a beautiful quality,” and were provided by his gaffer Frans Weterrings.

While Ruhe describes it as “a simple film,” one intriguingly complex scene was a two-minute car ride, around the block, when J.R.’s absent father suddenly shows up, and “it was clear that (Clooney) wanted it in one shot; it was a two-minute take, and he has to time it right.”

Perhaps inspired by Clooney’s own single-shot car ride with Brad Pitt in Ocean’s Eleven, the now-director “talked about it, prepared with the actors, and then we went around the block.”

There were two cameras hard mounted on the car itself, and then a camera car following, where “George had a monitor, and could listen. I think we did two takes on that, and then we had the scene.”

Overall, Ruhe says, “George wanted it to be a warm film. Not cynical, not distant. He felt in our times, you needed something warm.”

We certainly do – even out here in LA, with its already-warm, perhaps-too-dry 70-degree days. We’re surrounded by weather of all kinds, whether literal, medical, or political, most of which isn’t too tender, these days.

Meanwhile, on into award season, with its constantly shifting calendar, and one more winter column left, before spring arrives. See you then.

@TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com