We seem to live in constantly interstitial time now, always in the wake of “defining events”- until the next set of befores and afters comes along.

Hence, just when we thought we’d figured out how best to live with the prevalence of the Delta variant, here comes Omicron, discovered and travelling the world, all since our last column.

“Interstitial time” ain’t what it used to be.

So, will production restrictions get stricter again? Will theatres, hoping to entice masked crowds, for year-end tent poles, and any Oscar contenders not already streaming, really amass “box office” in any meaningful sense of the word?

These and other questions lingered during rounds that almost had a pre-plague familiarity. Here a premiere of Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley! There an Academy screening of Aaron Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos! (Both leading to insights from their respective cinematographers, in the paragraphs ahead!). And both in full theatres!

Indeed, the fullest we’d been in since, well, you know.

Vax cards were checked of course, and masks required, but there we were, in the dark, looking up at a big screen.

Similarly, a publicist friend cajoled us into heading downtown on a recent weekend to the Los Angeles Comic Con, which had moved faster than the premiere pop culture version in San Diego in getting back to a full live version, with nearly 95,000 in attendance.

It was still surprising to see a convention hall more or less full of people, who were more or less masked (though interesting questions arose: does your cosplay mask count as a “mask,” for instance?), except when doffing them to eat in an also-full food court – which still felt like an act of faith.

We contented ourselves with a few panels in lesser-trafficked corridors, including one on the coming new paradigms of virtual and augmented reality. The panelists were all designers or programmers of immersive digital experiences, or reviewers of same, one of whom declared “I live, basically, my whole life virtually,” adding that “my virtual body feels as real as my real body does.” Since this comes on the eve of seeing the new Matrix movie (which current embargoes prevent us from writing about at press time), one wonders if the future has already snuck up on us while we were busy spending most of the previous year(s) in front of Zoom screens.

And while the idea of interacting with your screen – immersing yourself in it – has been around for at least one whole wired generation, perhaps the seeds of such ideas came from routinely welcoming fictional characters “into” our homes – having the screen come to us. And one of the shows – perhaps the show – at the genesis of all that was TV’s first big hit, I Love Lucy.

Amazon’s Being the Ricardos is Aaron Sorkin’s take on the lives of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, and the ways they pioneered their new medium (long before Desilu greenlit Star Trek in the 60s). Nicole Kidman and Javier Bardem play the couple, dealing with events in a singular week (collapsed from a timeline spread over the 1950s), such as a McCarthyite Red scare, Desi’s increasingly well-known infidelities, and Lucy’s on-air pregnancy.

The pregnancy alone was groundbreaking, as it initially violated broadcast standards which seemed to suggest children were still delivered by storks. Other innovations included the three-camera setup, and the invention of the rerun (and thus, syndication), as the actual film that I Love Lucy was shot on (as opposed to kinescopes taken from monitors during the “live” East Coast version of a show) resulted in an available library of what we now refer to as “content.”

And speaking of “content,” it was in shooting the Facebook/Zuckerberg biopic The Social Network, that Oscar-nominated DP Jeff Cronenweth ASC first met Sorkin, who of course wrote the film that David Fincher directed.

Well, according to Cronenweth, mostly directed: That movie, he told us, brought together “an amazing group of people.” So amazing, perhaps, that, hoping to avoid a phalanx of farewells on the last day of shooting, “Fincher left so he didn’t have to get sentimental – and asked Aaron to direct that (final) scene.”

So technically, then, Cronenweth had worked with Sorkin as director once before, so when the now fully-directing writer gave him a call last year to ask, “if I was interested – I was beyond excited.”

The story unfolds “in writer’s rooms, on the set,” and other well-designed locales around Hollywood, but the visuals weren’t there to simply recreate the look of I Love Lucy. After all, he observes “I also have an audience that grew up on Game of Thrones– I don’t think people would appreciate it if we stayed (strictly period),” hence the film moving between B&W and colour sequences.

“I used the RED Monochrome camera – it had a little bit more contrast, and a little more highlight to those images.” Another novel use of RED came with the 8K RANGER, with Cronenweth being “the first person to use ARRI DNA glass on a non-ARRI camera.”

The innovation went to capturing a story about a Hollywood couple who were innovators themselves. Both Desi and Lucy wanted to stay in Los Angeles, instead of moving to New York, where most live TV was done.

As part of reimagining how to do sitcoms, “they hired a guy named Karl Freund,” who was not only an ASC member, but had merely shot Metropolis, Dracula, won an Oscar for The Good Earth, and helped invent the tracking shot with invention of the unchained camera.

Desi had some revolutionary ideas of his own: “He wanted to shoot it with three cameras, so they could do it in front of a live audience (and) they’d shoot on film, then edit – (then) go live across country at same time.”

“It was more expensive to do that,” Cronenweth says, “so Desi and Lucy absorbed those costs.” And of course, also happily absorbed the rights for the perpetual syndication.

“To this day, the three-camera setup is done that way,” Cronenweth adds.

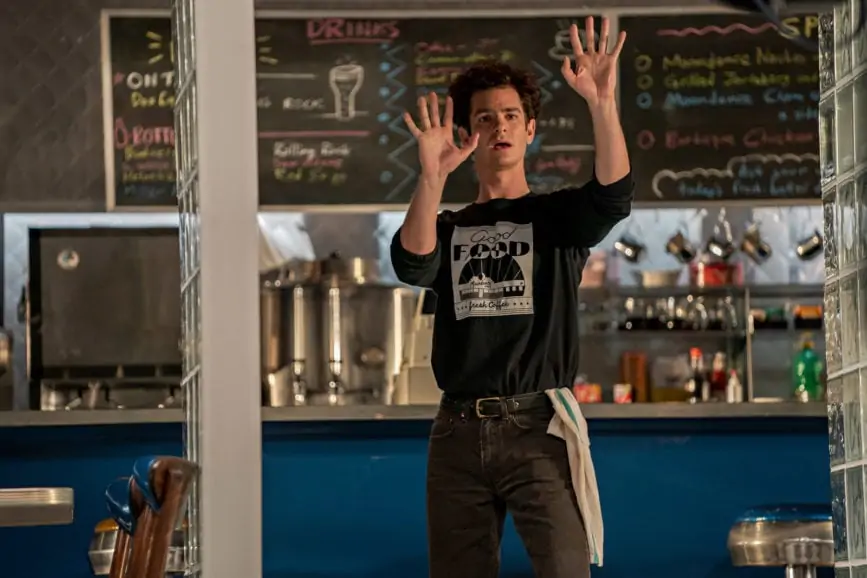

Cameras and innovators also played a role in how Alice Brooks – herself a newly minted ASC member – shot tick, tick…BOOM!, the Netflix-produced biopic with Andrew Garfield portraying Rent creator Jonathan Larson, who died suddenly a couple of days before the hit musical’s opening night.

She’d had a previous collaboration with director Lin-Manuel Miranda similar to Cronenweth’s: Miranda had written her earlier (also musical) feature, In the Heights, and on the last day of shooting that film, she received a call to meet with the director-bound writer.

“Page by page I turned the script,” she recounts, “these could be scenes from my childhood.” Not only because she grew up in 80s-era New York, but even more specifically, because “my father was a playwright, and my mother was a dancer.” She’d watch the creative “struggle” unfold “every day… But we also had a house full of creative people, like Jonathan. (The song) Boho Days could’ve been any day at our house.”

In addition to the “blurred lines of dream and reality,” from a 10-year-old’s recollections, Brooks’ other guide for capturing these “Boho Days,” was a voluminous videotape library:

“We had eight years of videotape of Jonathan – it was remarkable. His friend had a camera and recorded him constantly. And he was being recorded never thinking anyone was going to see this” – a quite reasonable assumption in those very pre-TikTok / Instagram days.

“And as we’re watching, I’m slowly falling in love with Jonathan. This joyous, wonderful human who never stopped working at the Moondance Diner – and died in that apartment. The dreamer who dusted himself off (and) never got to enjoy success. We bookend the movie with these Betacam shots – sort of like the found footage quality too, of his life.”

In finding her footage for this film, Brooks used a Panavision DXL2. “I’ve shot with it a lot,” and when she did camera tests, she asked Miranda if he wanted to come along. His reply was that he wanted “to know everything,” later asking questions like “what do you like about this frame?”

Brooks liked those frames even more when they “stripped a tonne of the coating off the lenses,” a set of G Series Anamorphic Primes, also from Panavision. “We wanted them to feel imperfect,” she says. To perfect that imperfection, they “added film grain,” and further texture with the lighting.

Because so much of the movie is environmental, she says there’s also “a lot of darkness,” all of which felt “period appropriate.”

Of course, darkness wasn’t restricted to Reagan-era New York; there’s plenty of it now, and about four decades prior to Rent, prevailing darkness gave birth to the entire genre of noir.

Tyrone Power’s decidedly unromantic lead in the carnival-set Nightmare Alley is one of that genre’s staples, and this season offer’s Guillermo del Toro’s version of same novel that inspired the original.

Bradley Cooper plays the carny-spawned “mentalist,” who takes advantage of poor marks, and later – smoothing his act – some very rich ones, until he meets his ethical match (or lack thereof) in Cate Blanchett’s psychotherapist.

Cinematographer Dan Laustsen ASC DFF, returned after Crimson Peak, and an Oscar-nominated turn on The Shape of Water, for another collaboration with the director.

“This is our fourth movie together,” Lausten says, harkening back to their first pairing in the late-90s “bugs amok” film Mimic. The director had sent him Nightmare Alley’s script, and already had “some strong ideas about the color palette for the scenes.”

Among them was that “skin tones should always be a little brighter than the walls,” with the director using visuals – “where do we want to go colour-wise?” – to chart the unfolding story.

Cooper’s Stanton Carlisle begins his journey – or descent – under stormy skies as he arrives at the carnival, where, Lausten says, “we had this idea to have a lot of smoke. We split between steam and smoke – steam is a little slower,” and hence, easier to capture.

And Lausten doesn’t like to leave much to chance. “I like lenses,” he says. “We want to be in 100% control (and we) want lenses to do what I’m expecting them to do.” To fulfill those expectations, he used ARRI Signature Prime Lenses on an ALEXA 65 but didn’t want to put that camera on the Steadicam, so when it needed to move, it would be on cranes and dollies.

An ALEXA Mini LF did wind up on the Steadicam, and of large format in general, Lausten says “it’s even better for the close–ups.”

As for colour palettes, you might think they’d play a large role in the ever-expanding year-end streams of holiday fare, appearing on Lifetime, Hallmark, and in this case, Netflix. A little blue or silver, perhaps, if there’s a Hanukkah subplot, but otherwise, lots of greens and reds – and not the muted stuff you’d find in a Depression-era carnival.

But Brad Rushing CSC says it ain’t necessarily so. He shot last year’s California Christmas, and this year’s California Christmas: City Lights. with a RED Ranger GEMINI, with “vintage Kowa anamorphics,” but says the holiday aspects don’t affect his choices “nearly in the same way it does production design.”

Though being “very cognizant of colour,” he also feels quite “liberated by RGB LED lights. I spent most of my career using HMI or tungsten light, and if I wanted colour,” he was always restricted to what gels were on hand. Now, he says, “I can have the lighting team remotely on a walkie, rather than entering the set.”

As colours used in stories set during generally snowless California Christmases, he noted that in the current one, “there’s a scene that takes place in a mission that serves people who are homeless… and there was a Christmas party, so I complemented that by using a little bit of red lighting.

“We also had red lighting in the climactic scene of the first one, where they’re in a big barn. I needed more festive (lights) – those kind of plywood walls didn’t feel right. I put some ARRI SkyPanels in there and washed the whole thing in some red backlight.”

Images from that scene, it turns out, were used heavily when Netflix was promoting the film,

May your own holidays be bright and/or subdued, as you see fit. We will see you back here in a whole new year. Until then, in this interstitial stretch, take care.

@TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com