It seemed, for a week or two in June, that perhaps this column would revert to a semblance of its pre-pandemic self, with the distracting rhythms of Emmy and Oscar season once again insinuating themselves into conversations about, and the perception of, shows on both the large and small screens. Perhaps we would see each other at Cine Gear, or NAB which, after rescheduling, now come almost back to back, later this fall. And perhaps we still might. Except if we do, it seems we’ll all be wearing masks again, at a minimum.

It’s almost hard to keep up with the news on that front, from one column to the next. As we were writing last time, LA county “recommended” a return to indoor mask wearing, even for vaccinated folks. Since then, that’s become mandatory.

And The Wall Street Journal reports that “production of movies and TV shows is getting disrupted again because of COVID-19 and uncertainty over vaccination protocols, a setback as networks and streaming services remain hungry for fresh content.”

As the song says, it might as well be spring. And if we’re not careful, that could wind up as “spring of 2020.”

Though as some of this month’s DP interviews reveal, the protocols already used for a lot of the productions currently satiating that aforementioned hunger, are becoming almost routine, for those behind the lens.

And they’re still able to work at inordinately high levels of their craft. So high, in fact, that in some cases, per the recent Emmy nominations, they practically have entire categories to themselves.

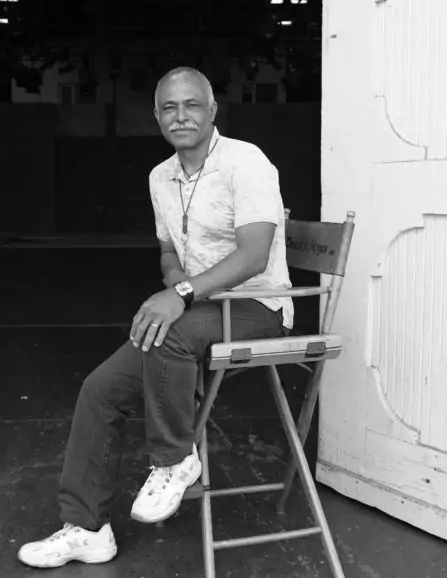

Such was the case for old friend of the column, Donald A. Morgan ASC, who we talked to last year when he was nominated (and ultimately won) for best cinematography in a multi-camera series, for The Ranch. Since Morgan has been a “regular” in that category, for The Ranch, Home Improvement, and other shows, it wasn’t a surprise he was nominated again. But even for a man of his talents, it was a little surprising that he took three of the available five slots this time – for three different shows.

The trio in question were Last Man Standing, in another long-standing collaboration with Tim Allen, ABC’s now post-Roseanne The Conners, and, for Netflix, The Upshaws.

He was still trying to “wrap his head around it” when we dropped him a line after the announcements, and a bit later, after some time to process it all, wrote at greater length that it was always an “honour to be nominated by your peers, but this was a real shock!”

He also briefly broke down the differences in the three shows for us, with Last Man Standing being “a clean show, not much diffusion. But we tried to push more light sources through windows this season.”

On The Conners “we went with a little moody look, but not too much (since) it is a comedy. But it does cross into some heavy subjects. I took it on a rollercoaster ride!”

As for The Upshaws, which he noted was about “a black family that has a great business” (and quite a lot of relatives, in the manner of sitcom tradition) “I went softer and (also) a little desaturated.”

That desaturation clearly paid off. And if that term denotes a kind of adaptation of the colour spectrum, adaptation was also one of the hallmarks of how Morgan was able to oversee three different shows – during a plague year: “It was crazy in 2020, working the first two months of the year, then we got shut down because of COVID for seven months. And then I took on two projects after we came back. Wow! All I can say is thank you to my three different crews!”

Initially, it was “merely” two different shows, with Morgan shooting Last Man Standing on Mondays and Tuesdays, and The Conners on Thursdays and Fridays. “I’m a group A for both shows, (which) means testing three times a week for both shows (with) two different testing companies. So, it got pretty crazy, but no one got sick between both shows!”

We, of course, will hope it stays that way for Donald and everyone else. As for “everyone else,” this is also the time of year – along with Oscar season – that we like to chat with the other craft collaborators who work with cinematographers to deliver all those nominated visuals. It takes a village – video or otherwise – to make a show, and not only (as in the case of Mr. Corman, see below) one that seems clearly “effects-driven.”

But in a show that does rise or fall with the veracity of its VFX, it might be more important to note how critical the DP’s role is. Such was the case with Amazon’s renowned graphic novel adaptation The Boys, which asks “what if superheroes were ‘super,’ but not really all that ‘heroic?’”

This year, the show has nods that include outstanding drama series, and one for its effects work, so we asked visual effects supervisor Stephan Szpak-Fleet how he works with the show’s various cinematographers:

“One of the keys, to me,” he writes, ‘to great, grounded VFX, is our collaboration with Camera.” (The upper-casing is his, by the way, and we like what it signifies about the relationship between departments.) “The camera is another character serving the story, and we have to respect it, its rules, its language, its flow.”

He goes on to note that the interaction of VFX and Camera “is one of the most unique aspects of the show, and one of the things I love the most about working on it. Whenever we go into a heavily technical situation, we’re super prepared. But we also know that we have to let things breathe. We have to allow the camera to be the right kind of eye to tell our story. So, we’ve built all these ways to adapt quickly. For instance, we very minimally use blue or green screen on the show. We do that so we can keep the camera flowing and the lighting real (and) organic.”

Somewhat surprisingly then, for a VFX-nominated show, “we rely more on rotoscoping or cleverly composed frames. Another example is, even if we do a lock off for visual effects, we study the handheld nature of our camera moves and will apply that to our lock offs.”

Handheld camera moves, and their simulation, were also part of the pipeline for Apple TV+’s Mr. Corman, which arrives this month. Created by and starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as a teacher in the San Fernando Valley (from whence this column originates, and where Gordon-Levitt originated, as well), the versatile actor imagined the show as a kind of counter-history of what his life might have been, had the acting muse not been so kind to him.

Of course, there is plenty of contemporaneous angst in the show – though like Hacks, which we wrote about last month, a pandemic isn’t part of it (just a lot of 21st century anomie, random mortality, and in a couple of FX-y sequences, a Melancholia-like meteor, hurtling to Earth, as a presumed externalization of the title character’s apocalyptic inner turmoil).

Shot by Jaron Presant ASC, who’d collaborated with Gordon-Levitt on earlier starring projects like Brick and Looper (and who shot second unit on Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which was also done by Rian Johnson, who wrote and directed those earlier projects), he says the show was nearly cancelled by the world-changing “meteor” of the Coronavirus.

“Corman started in LA, pre-pandemic,“ he recounts, “then we shut down because of the pandemic. We started to prep for picking back up in LA (but) the protocols were so strict, the cost of starting back up was too extreme.” The production then “made a last-ditch effort to keep the show going by moving to New Zealand.”

Shooting outside of America’s shores has since agreed with him – he was on a seemingly bucolic Greek isle when we talked. As for the series he began in LA and finished across a different ocean, he says “Joe wanted the show to let the actors shine, and let the performances play… The camera is psychologically linked to (Levitt’s character) Josh – kind of an active player, a conscious player within the scene… almost like another cast member.”

That approach drove a lot of the show’s recurring long takes, as the camera reflects the generally unsettled inner lives of its characters. But short take or long, Presant captured it on “Alexa Mini LFs with Ultra Primes – detuned by Guy McVicar at Panavision, to a specific match he did on another show for me. Which makes them really shine in close-ups, and the way they go out of focus is really beautiful.”

For the image pipeline, which included FotoKem’s nextLAB for mobile dailies, everything was “based on (film) print emulation… with modifications based on the fact we’re doing HDR… I added grain that was based on film’s probability for grain structure and added gate weave.”

And there was – a la The Boys – even a “handheld algorithm – based on actual handheld footage,” which was made into “a scalable algorithm,” which was then ported into nextLAB, and then into Resolve.

But besides the careful flow of digits, Presant is also quite passionate about lighting, saying it’s “where camera was, five or ten years ago. To me, the most exciting part of cinematography today is in lighting…it’s analogous to the onset of digital cameras. The changes are happening so fast.”

And within lighting, he’s passionate about xy (or Yxy), a kind of three-axis approach to conceptualising lighting, wherein xy are the colour coordinates – visualise them on a 2-D plane – and over them, another “Y” axis (making the conceptualisation now 3-D) representing luminescence.

“Using xy to light,” he says, “is all about the colour of lights before they are captured by the camera. So, while the LUT is dealing with luminance and colour values from the camera downstream, lighting is happening upstream of the image being captured by the camera. It is lighting the set. Using an xy chromaticity coordinate system to drive our lights means that we can make very specific colours very quickly and very accurately. Creatively what that means is that we can make a world that photographs as completely natural despite our manipulation of light in a scene. And while we have done that for years, the accuracy of colour means that the line between where the practical lights end, and our movie lights begin is completely hidden.”

There’s a lot more to say just about xy, but we’re running long this month, so we’ll endeavor to pick up this conversation again. But as for the blurring between the practical, or “real,” and the artifice of movies and entertainment, well, that seems to be the particular axis all our lives are being played out on, now.

See you in September. Meanwhile, AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com, and/or @TricksterInk.