NAUTICAL ILLUSIONS

Rear projection techniques helped create a stylised and dynamic environment to transport viewers back to the early 18th century to learn about the real pirates of the Caribbean in Netflix’s docudrama.

“The unique challenge of telling stories set at sea and in exotic locations on a tight budget appealed to me, but it required creative and pragmatic thinking,” says cinematographer Robin Fox, sharing his experience of helping tell the origin stories of characters such as Blackbeard, Black Sam, and Benjamin Hornigold in The Lost Pirate Kingdom, a Netflix docuseries mixing dramatisations of historic events with expert interviews and commentary.

Excited by the prospect of bringing the fables to life and charting the rise and fall of the early 18th century pirates in Nassau, Bahamas, Fox worked closely with lead director Stan Griffin to create a “gritty, dark, and seedy” world because, as Fox highlights, “there’s nothing glamourous about the life of a pirate!”

Due to the short lead time, focus was placed on finding a way of working which allowed the directors – Griffin, Hereward Pelling, Patrick Dickinson, and Justin Ricketts – to be uninhibited when telling the stories. Inspiration came in the form of a production focusing on a very disparate world to The Lost Pirate Kingdom – sci-fi thriller Oblivion (2013), which was shot by Claudio Miranda ASC using a rear projection technique incorporating 20,000 lumen projectors. “I remember thinking it was a fantastic way to incorporate a virtual space and I always had it in the back of my mind,” says Fox. “Claudio used 21 projectors in a 270-degree set-up which wasn’t an option for us, but we looked into whether we could do something similar.”

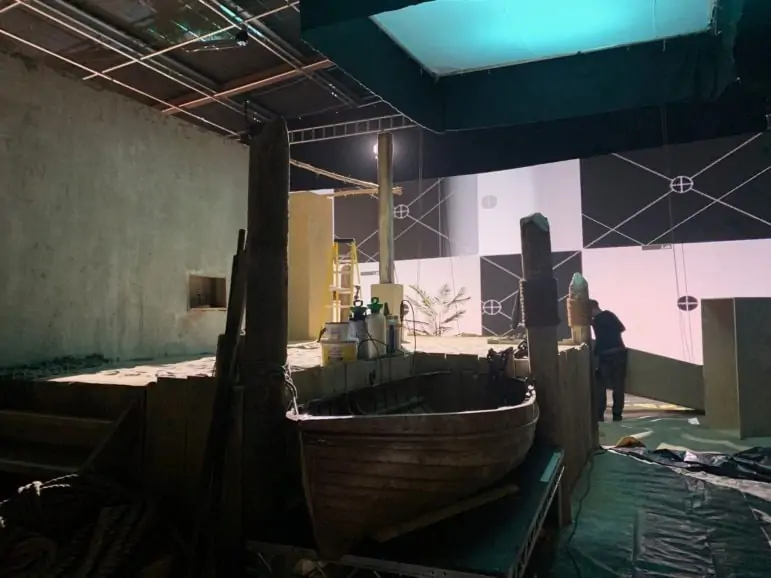

With location versus studio was still being discussed three weeks prior to shooting, ultimately it was decided that shooting on location over three weeks in November and December 2019 would be prohibitive. The crew therefore opted to create most of the environments surrounding the characters using rear projection at West London Studios on a dry stage housing the tavern, harbour and beach sets and a wet stage housing the pirate ship. The remaining 20 percent of the series was filmed on location at Charterhouse in London and on board a replica of the Golden Hind galleon in the South Bank in London.

The team began developing the rear projection technique – which would be used for scenes requiring a nautical or Caribbean backdrop – working with projectionist Matthew Button to shoot tests as proof of concept on a three-metres square screen. This was scaled up to a 60-foot by 20-foot screen for the shoot and relied on three Panasonic DZ21 20,000 lumen projectors and a Catalyst media server. Combining dynamic animation and rear projection on a huge scale with a 30-foot revolving stage to move the pirate ship, the crew successfully recreated Nassau in 1715.

When greenscreen was discussed as an option, Fox revisited Dark Matters – a docudrama about bizarre science experiments throughout history that he shot in 2011. “The furniture and props were real, but the rest of the sets were CGI. It had a B-Movie and comic book vibe which was great for the subject matter but not what Stan or I felt was right for The Lost Pirate Kingdom.”

Using rear projection was deemed more suitable than green screen due to the shallow depth of field achievable in camera without strange rotoscope effects being produced. “The bi-product was a 2D effect because, unlike working with an LED volume, we could not correct parallax,” says Fox. “It gave the feeling of shooting against moving matte paintings which I didn’t mind on this occasion as it was part of the stylised look we were aiming for.”

A period feel was achieved with help from production designer Richard “Badger” Touch’s design and props, Julie Elgar’s costumes and makeup by Ruth Pease. Touch designed a virtual layout of the dry stage using SketchUp to ensure three sets could be placed so they were oriented correctly on the stage and utilised the same screen. “He also cleverly repurposed each set to be used as different locations which was very successful when combined with the various animated backdrops,” says Fox. “Wall torch holders and fire baskets were also incorporated to create a warm fire light in the night sequences. The harbour scene was built around 3 feet off the floor to enable water lighting effects and low angles.”

Marine designer Tom Cochrane, who designed the ship set, “went above and beyond” to design it to fit on a 30-foot stage revolve to orientate the ship to screen and was accommodating throughout, fitting the mast under the crew’s softbox lighting rig.

Delivery requirements outlined that The Lost Pirate Kingdom would be shot in HD which allowed Fox to shoot, primarily handheld, using his “trusty” ARRI Amira as the main camera paired with Canon Cine Primes to achieve the required shallow depth of field. “I’ve owned the Amira for more than five years and use it for documentary, commercials and drama. It still puts out as good an image as any other camera in its class today,” he says. “We wanted nice fall off against the backdrops as the screen works best when it was thrown out of focus by just the right amount. We staged most of the action at least 20 feet from the screen which resulted in the desired drop off when working with the Canon lenses.”

Fox often uses ARRI Look Files as the basis for his LUTs, from ‘50s retro to bleach-bypass. “I like their Film Look B as it is very cinematic and puts a slightly smoky blue hint in the shadows which I love. I also added some green in camera to really grunge the image up,” he says. “The series needed to look as cinematic as possible, given the constraints. Early on, we realised we would need to shoot 2.35:1 to avoid shooting off the set. It wasn’t until we got on set and the live picture corresponded exactly with SketchUp that it was given the green light by Netflix.”

The series saw Fox collaborate with fellow DPs Tom Pridham and Martin Kobylarz with them shooting on location, shooting below deck on the Golden Hind and at Charterhouse, whilst Fox oversaw the studio shoot. Other key members of the crew included gaffer Callum Collins, 1st AC James Abbott, 2nd AC Azu Ekwukoma, rigging gaffer Ed Smith and Liteworx, and location gaffers Robbie Smith and Nik Lekaj.

Fox also teamed up with visual effects specialist JP Hersey at Stonesoup VFX and director Griffin to develop the backplates whilst considering the changing position of sun, foliage, colour temperature, and brightness. “He had hundreds of plates to use on top of all the animation, created from bespoke CG, library footage and stills, all in 4K. He did a great job,” says Fox.

Being a fan of mixed lighting and the combination of fire and moonlight in period dramas, Fox worked with gaffer Callum Collins to add green to softboxes used overhead and to the fill light to create the required “dark, seedy, and intimate” feel. A slightly cyan blue was also used for the moonlight and desaturated with the LUT and then later in the grade. “Brown, bluey-greens and golds were the order of the day,” says Fox.

While the crew was shooting on one stage, they could pre-light the other stage. Fox and Collins worked with ARRI SkyPanels and ARRI’s intelligent lighting control app Stellar to pre-programme looks and lightning effects. They also used a 12×12 softbox over the harbour set with four S60s passing through ½ grid cloth diffusion and a 20×20 softbox with eight S120s above the ship set.

“When we got the projection screen and softbox set up we realised that the spill from the top light, even with a skirt around it, was washing out the projection and we needed a 20×20 egg crate to keep spill off the screen. Liteworx did a fantastic job getting one at late notice and Callum and his team were incredible at installing it in situ,” says Fox.

“As the ship was on a 30 foot revolve, we could angle it to always be in the right orientation for the way we were filming for the screen. This meant Callum could pre-rig the back lights and the softbox so we were always lit as long as the boat was in the correct position for the screen.”

The series required a mixture of day and night interior and exterior scenes shot on both stages. Early in prep, the team decided that the sun should be low in the sky for day scenes, “like the sunrises and sunsets you would normally want on location”. JP Hersey also incorporated the low sun into all daytime plates for the background along with the moon for certain scenes.

“When you’re working with rear projection everything has to balance to the screen, so it can only be as bright as the screen can go, which in film terms isn’t very bright,” highlights Fox. “As matching the screen light levels were very low – effectively T2 at 400ASA – interior scenes were largely lit using Rifa Lights. The incandescent light they produce is great on skin tones and when dimmed slightly is a great match for candlelight.”

The brighter daytime scenes were difficult to illuminate; achieving a bright Caribbean vibe whilst maintaining an overall level to match the screen was a challenge. “The brighter you go, the more spill you have on the screen which is why we kept a low backlit vibe whenever possible,” he says. “Working with four directors across the six episodes could also be challenging as we were often shooting out of sequence which sometimes made it difficult to keep track of where we were in the storyline.”

When working on a stylised docudrama such as The Lost Pirate Kingdom, the key to success, according to Fox, is to decide on an approach early in pre-production and “prep that to the max”. “The longer you flirt with other ideas, the less time there is to collaborate with other departments on a unified approach.”