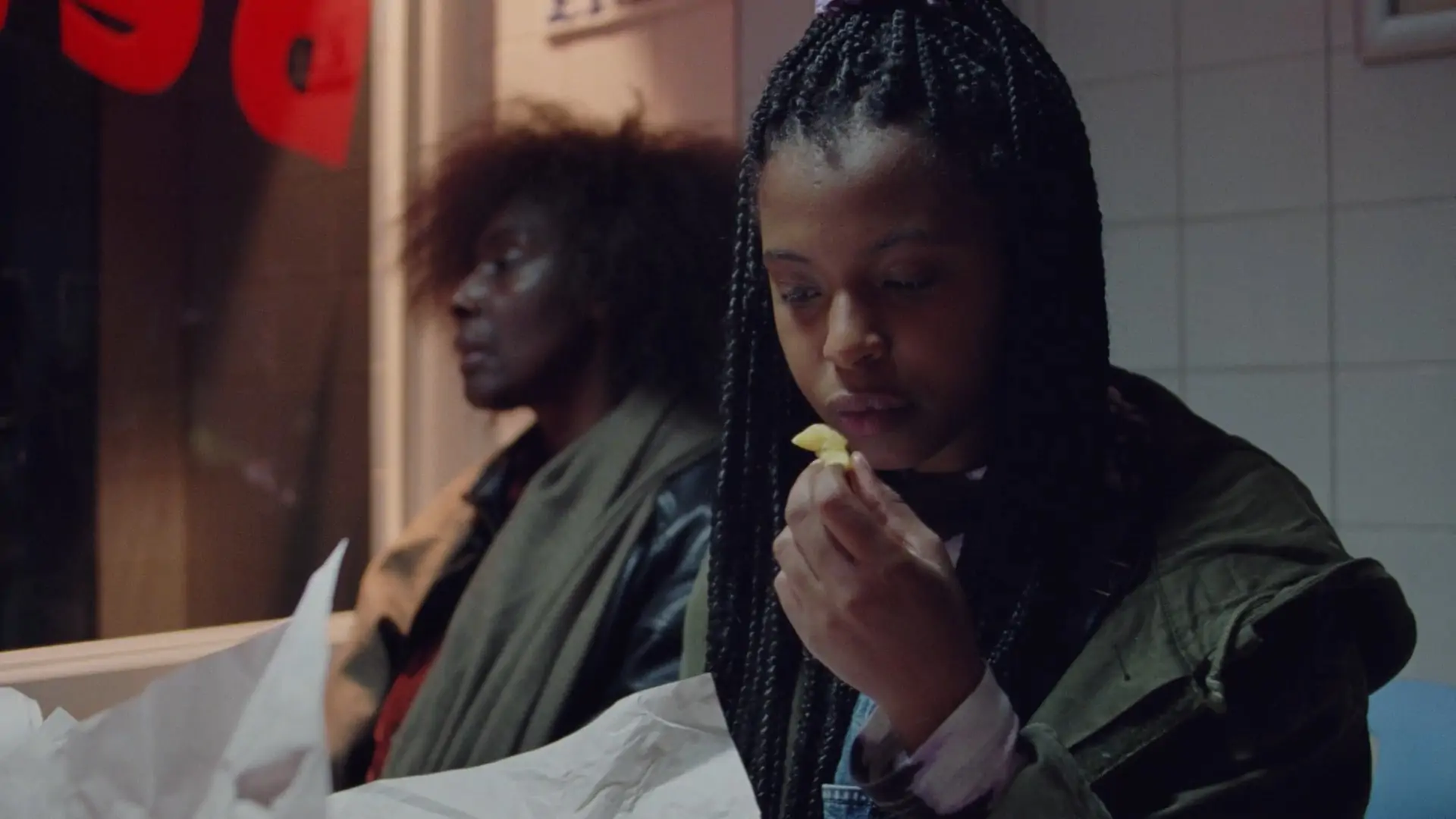

Overview: When 18-year-old Nneka attempts to connect with her estranged mother, the fantasy of who she is, is abruptly shattered by the harsh reality of living with mental illness and extreme poverty.

What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

The Visit is a semi-autobiographical account of the first time director Ebele Tate visited her mother in Edinburgh after being estranged for many years. The romanticised version of who she imagined her to be is abruptly shattered by the harsh reality of her mother living with mental illness and in extreme poverty.

We spoke at length about intending the film to play out as a sense of looking back – memories of time, space and place. The temporal ambiguity required the actuality to be slightly heightened in subliminal ways. This was paired with the protagonist’s fantasies, which went one step further but were balanced to remain coherent within the world of the film.

As a result of it being a memory, it is strongly placed in the protagonist’s experience and while she is trying to navigate her relationship with her mother, we wanted the viewer to feel exactly what she is feeling. The lack of access to the mother’s condition, moments of extreme connection as well as despair are all from Nneka’s perspective.

What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

In pre-production, we looked at films like Ratcatcher, Moonlight and Red Road for their poetic approach to complex interpersonal relationships rooted in a social realist setting.

We were also highly inspired by the beauty in the mundane as reflected in the work of George Shaw. The social commentary intrinsic to the image was a great starting point for the themes we wanted to represent in The Visit. The paintings of Paul Signac with its impressionistic and textured tones were a reference for the dreamscapes within the film.

What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

The initial plan for the film was to shoot it entirely in Edinburgh where the story is based. However, a large part of it occurred inside a council estate flat and that was one of the hardest locations to find considering the COVID restrictions.

We eventually shot the exterior locations on a moving bus in Edinburgh, the dream landscapes in Wales, the chip shop and the pub in Slough and Woodburn Green respectively and the interior of the council estate flat was a set build on the NFTS Main Stage. One of the challenges of the shoot was to accommodate all the locations within eight filming days, which amounted in location moves almost every day.

Finding the dream landscape with the house next to the sea, the way Ebele Tate imagined it, was a task producer Danielle Goff and production manager Elizsa Diaz championed. The juxtaposition of the urban gritty landscape of the estate with vibrant wild natural dreamscape was central to the story. However, we didn’t have the time or the budget to stay overnight in Wales and the only possible solution, without rethinking the entire sequence, was to travel to and from Wales within a shooting day. It gave us close to three hours of filming at the location and it was extremely tight but the entire team pulled through to make it achievable.

Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses and what made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

We decided very early in the pre-production process that we wanted to shoot on 35mm film. The texture of film served well to extend the existing thread of finding beauty in the banal as well as to represent the delicate relationship between the mother and daughter.

The choice of stock however required some testing. I was a bit concerned about the amount of grain on 500T in some particularly low light locations we were filming. With the help of Sam Clark at Kodak, we were able to get our hands on some film stock and to conduct tests. I was pleasantly surprised by the minimal grain on the negative and decided to shoot the entire film on one stock (500T/5219) to keep the grain structure consistent.

We were shooting during late August – early September, possibly the busiest time post the COVID lockdown. This made getting a camera kit together extremely difficult, but with the support of Lee Mackey and Kirstie Wilkinson at Panavision, we were able to shoot on a Panaflex Millenium XL with Panavision Primos, which was an absolute dream. I am incredibly grateful for their generosity and patience in trying to accommodate our specialist lens and grip requests.

What role did camera movement, composition and framing and colour play in the visual storytelling?

Nneka had painted a picture in her head of what her mother was like so we embraced the idea of presenting it as if it was a tableau. We used static and considered frames, often repeating framing with the characters interchanged to depict a shift in power. There was a conscious decision to refrain from panning or tilting to reframe, thus reinforcing the rigidity especially within the flat around Patrick’s presence. This sense of oppression is reinforced with high angle shots and overhead lighting. We also capitalised on the depth of field on 35mm to isolate Nneka in her surroundings as she feels like an unwelcome outsider.

The Visit is extremely reliant on senses and thus the mood and atmosphere were extremely important. The sense of unease on arriving at the estate, the first recognition of something amiss with the mother, and the first time Nneka is allowed to take on the role of the child are treated by heightening the romanticisation or haunting through precise camera movement and framing. This is in contrast with the dreams where the movement is fluid and organic.

The colour purple imbued a lot of symbolism for the director and it was worked into the costume, production design and later in the grade in varying amounts. It reached its complete actualization in Nneka’s dreams.

What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

Nneka’s pursuit of her relationship with her mother is the primary journey we follow through the film. Sometimes she finds a moment of connection but often it seems to evade her. We wanted to reflect that in the lighting (especially in spaces like the flat) by placing the key light so that it was never directly on her. To carry forward the overbearing feeling, the lighting fixtures were often overhead. We shaped it to avoid the shadows under the eyes for Nneka but kept it rather harsh for Patrick to represent the way Nneka remembers him.

In order to reinforce the idea of memory being an unreliable source, we wanted to play with the idea of the backgrounds receding to black, as if it’s slowly fading away. Knowing that we wanted to shoot on film, we embraced that on our night exteriors.

The Steadicam sequence shot at night on an estate in Edinburgh with solely battery powered lights on film was a bit of a task to tackle. I had taken some film stills during the recee to Edinburgh and had rated 500T at 800 ASA and 1000 ASA. This helped me understand the limit to which I could push the film. Then I meticulously planned where the five fixtures were placed to give me some accents on Nneka as we choreographed the Steadicam move through the space. I also used the headlights of a passing car and highlights in reflective surfaces to avoid areas without any detail.

Which elements of the film were most challenging to shoot and how did you overcome those obstacles?

Besides the fact that we had to shoot across numerous locations in a limited amount of time and make them look coherent, The Visit had a few elements – like the ceiling being filled up with water, a corridor being set ablaze and a flooding bathroom – that were challenging to pull off. We put together a list of ways to achieve them but slowly eliminated our way through it considering our budget, time and resources.

With the help of production designer Milly White and model makers Penelope Konstantara and Agatha Roudaut, we built a miniature of the room with the ceiling on the ground and a small tank around it which water was pumped into. Getting the scale of the model right, as well as the correct frame rate to make the movement of the water look convincing, required some trial and error.

Shooting on a moving bus was a first for me. We had a fantastic grip in Edinburgh, Jon McCormick, who helped us move quickly between set ups considering we had a deadline of two hours to finish the scene. The tight space necessitated adapting quickly to being unable to achieve certain framing and finding solutions.

What was your proudest moment throughout the production process or which scene/shot are you most proud of?

The schedule was such that we were often moving locations and once on the sound stage, moving from day to night within the council estate set within the same day. It required the camera and lighting team to be prepped and sometimes necessitated working efficiently by sending a few sparks to the next location/space to ensure we didn’t waste a lot of time when the cast arrived on set.

One of the sequences in the film that always gives me an intense emotional response is when Nneka is listening to Kelly sing at the pub. In keeping with the surreal tone of the film, we wanted to visually represent Nneka’s departure from her immediate surroundings. Gaffer Werner Van Peppen and I worked along with the sparks to time the fixtures in the scene to slowly and subtly dim down as we track in to Nneka. Needless to say, it only works because the performance of Nneka (Grace Saif) and Kelly (Leah Balmforth) is so powerful.

What lessons did you learn from this production you will take with you onto future productions?

I had the most hardworking and resilient team in Catharina Scarpellini (focus puller), Charlotte Vernet (loader) and Werner Van Peppen (gaffer), who pulled through despite the extreme conditions and tight schedules. Working on The Visit made me plan three days ahead and learn to communicate my intentions with my team efficiently.

It takes an army to make a film and it definitely took one for this. The innumerable and incredible sparks and camera trainees who came in to support us were invaluable to us being able to make the day.

The insight and advice of Stuart Harris, Ula Pontikos BSC and Angus Hudson BSC ensured that I was able to anticipate possible issues well ahead of the time and find effective solutions.

> DISCOVER MORE ‘FICTION’ FILMS FROM THE 2021 NFTS GRADUATE SHOWCASE

> GO TO BRITISH CINEMATOGRAPHER ‘HOME’ PAGE

> BACK TO TOP