This particular dispatch is being written during America’s de facto kickoff to the season ahead: “Summer,” if you’re looking at the weather and contemplating how many wildfires we’re about to go through on the West Coast, and wondering how crowded and unmasked your Memorial Day barbecue should be. “Emmy season,” if you’re thinking of a more showbizzy way of marking time.

And yet, by the latter metric, if we’ve just left “Oscar season,” it becomes harder and harder to differentiate the passage of time on the award-smitten calendar – much as wildfire and drought are now year-round considerations – if similar entities, like, say Amazon and Netflix, are lobbying to win both sets of accolades. And harder still, when one of those corporations buys a legacy brand, like, MGM Studios, which pretty much epitomised “the picture business” at one time.

So, mixed horizons abound: Are things really ever going back to the way they were, pre-pandemic, in terms of social cohesion, or simply going to movie theatres? Will Amazon start developing series for its Prime platform on the further adventures of the “00” unit, or Robocops being dispatched to quell election violence, or wherever else their newfound trove of IPs takes them?

Our colleagues over at The Verge came out with a pretty savvy take on the whole Jeff Bezos/Leo the Lion situation, which appeared on the eve of the holiday weekend. It’s made more so since they didn’t interview routine Tinsel Town pundits, but rather, spokesfolk from places like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, whose associate director of policy and activism, Katharine Trendacosta, said – among many other astute observations – that “every entertainment [property] is now a streaming service, which means they think of themselves as tech companies – which is incorrect.”

“Trendacosta added,” the article continues “that these services are all acting on a four-step business model: acquire IP, make as many things as possible, insert question mark here, and reach profitability. But that works only in the instance that the grand plan is to be acquired,” and then she cites Discovery, now part of what used to be “Warner Brothers”, as an example of the latter.

We haven’t even mentioned yet AT&T waving the white flag on its Warner Media acquisition, and spinning it off into a co-branded company with Discovery since last column, have we?

So anyone who tells you things are “settled” in terms of “pictures,” streaming, (or for our purposes, what the default platform should be that DPs should master and colour correct for, going forward), or anything else – all the way up to and including how the atmosphere surrounding the planet functions – is brimming with a kind of optimism that might be dangerous in front of barkers at a county fair.

Speaking of summery things.

Nonetheless, Emmys are indeed upon us, or at least, the “for your consideration” phase leading to eventual nominations, and we’ve been talking with a few cinematographers doing sterling work on those smaller, yet steadily growing, screens.

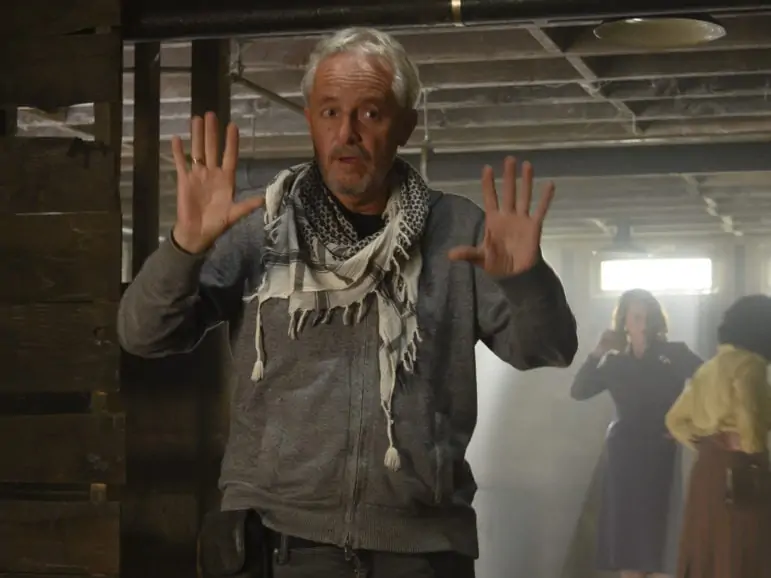

That includes the tandem of Checco Varese ASC and Xavier Grobet ASC, who shot Amazon’s THEM: Covenant from series creator Little Marvin. The story involves an African-American family in the 1950s, moving from the South, to Compton, then a spanking-new suburb outside of Los Angeles. And while the horror series features its share of otherworldly hauntings and creatures, the real horror, unsurprisingly, comes from how the neighbours react to their street’s first black family.

“I’m the least horror person you can imagine,” Varese says, “I get scared, I turn on the lights and don’t open the closet.” He also notes he’d already seen numerous horrors in his early years as a news cameraman, which took him from his native Peru to warzones and hotspots around the world.

But what attracted him to this project was “more about what was real, the horror of racism, the horror of the fear of the Other. It’s almost more horrible what happens to (the Emory family) for real, than what happens in their brains. That’s where I think Little Marvin… is so spot on.”

The producer was also pretty spot on in his first interview with Varese, when he pitched the visual style of the show by asking him to “imagine a 1950s classic movie, shot through the eyes of a 1970s cameraman, with the visual (tricks) of ’90s music videos, and the technology available in 2020.”

Varese might have found that kind of layering irresistible even if he hadn’t been nominated for MTV awards for his work shooting videos in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

Grobet notes that “Varese was the main DP and I followed what he and the director (American Horror Story vet Nelson Cragg) created on the pilot as the look of the show. Checco and I worked very closely and always shared our thoughts to keep it constant. Nicholas Kaat was our gaffer and he definitely helped keep the style similar. (While) each director brought a different look to the show, we maintained the basic elements to keep (it) cohesive.”

Those elements were captured on Sony Venice cameras, initially with the Anamorphic Hawk V-lite lenses on a 2.35:1 aspect ratio, “but later we decided to switch to the Hawks mini; we (found) that the minimum focus on those lenses was not enough for our needs. Any time we had to get the camera close to the actor’s face we had to use diopters, (though) I did like the distortion on these lenses, I think it went well with the look of the show, but being efficient was important.”

Varese echoes the sentiments about the glass: “Hawk came up with this series of lenses which is fantastic (and has) the bokeh of an anamorphic,” describing the minis as more of “an anamorphic simulator – a pretend anamorphic. It’s a fantastic tool; there’s very little distortion.”

Unlike the kind of emotional and societal distortion the show was trying to capture, in both the South recreated in “the hills of Santa Clarita (which) were a little bit greener. We made it warmer, yet more green – that created a nice contrast” and along with the almost Edward Scissorhands-like suburbs of Compton, which were actually a “backlot in Pomona.”

But the working closely and sharing thoughts didn’t just start with Them. Varese has known Grobet “for 30 years. I’m married to a director, she’s from Mexico, and she knows Xavier. We can’t wait to collaborate again.”

While they await word of a potential second season for the anthology-themed Them, Varese is working on the upcoming Dopesick for producer/director Barry Levinson, who directed the first two episodes, about one of America’s other pandemics, the opioid crisis. “The horror,” he notes, “is 450,000 dead every year.”

As to the more headline-grabbing, and even more pervasive pandemic we may or may not be emerging from, it directly affected Them’s production schedule as well. After they “basically finished shooting episodes one through eight,” Varese recounts, “nine and ten were left for after the pandemic.”

Which denotes a kind of optimism that an “after” was at hand. And while many productions were of course cancelled or delayed during that period, some tacked directly into the storm.

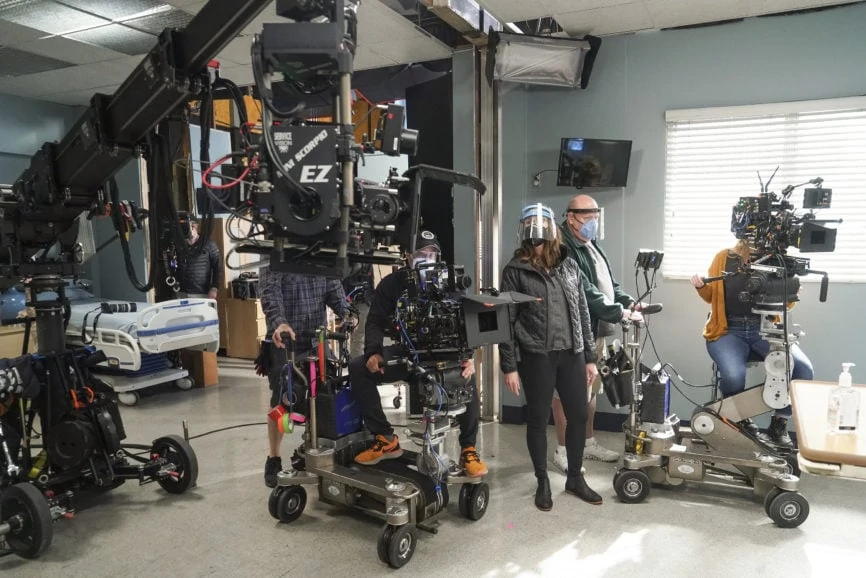

Such was the case with the just-concluded season of Grey’s Anatomy, where storylines – and production protocols – were quickly reworked, and the titular heroine, Ellen Pompeo’s Dr. Meredith Grey, spent much of the season in a COVID coma, hovering between life and death, and numerous overlapping storylines. On the show, when not sussing out their complicated love lives, the medical personnel were all wearing PPE, too.

As was the crew!

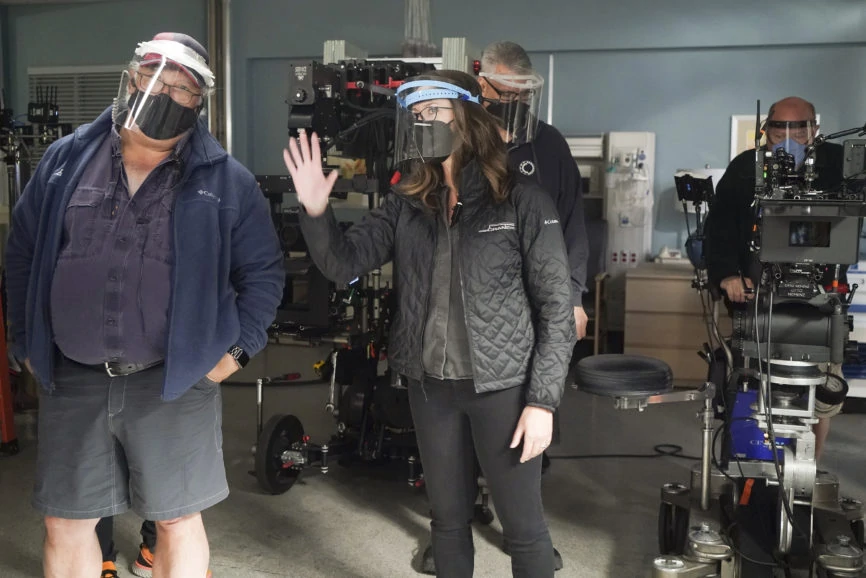

“They’re in full PPE, while we’re in PPE,” the show’s current lead cinematographer, Alicia Robbins, recounted. The procedures “made it incredibly difficult; just the day-in and day-out of us having to abide by these protocols,” while, of course, they’re shooting stories about characters who have to observe the same protocols, perhaps even more carefully, in a medical setting.

Robbins had worked on For The People,” the short-lived SDNY-set legal drama from Shondaland, the production company of Grey’s Anatomy creator Shonda Rhimes. Robbins was “C camera operating (and) while I was there, Grey’s Anatomy was looking for a DP to come out and shoot a couple of stand-alone episodes.”

That eventually lead to her working as alternating DP with the show’s long-standing cinematographer Herbert Davis, who “decided to leave last year.” So a couple years after wielding that C-camera, Robbins “was bumped up to lead director of photography for Season 17.”

So she arrived just in time to help chronicle the plague’s effects on the show’s characters, and live through its effects on set: “We had to make sure we were all watching out for each other,” she says, since “you don’t get as much oxygen. You’re dehydrated,” and masks often meant less liquid intake. “‘Have you had water today?’,” became one of the ways of checking in. “And the ability to gently admonish someone to “go get some water right now,”also meant some flexibility with the already-limited crewing, such as a camera assistant bumped to operator, because “the AC had to get a drink of water.”

But through it all, they “pretty much maintained our ten-hour days that we were asked to do. We did not have to shut down due to COVID.” This was in part because they “didn’t do as much location work – most of it was shot at the stages,” back in LA, where they found “quite a few new sets being built,” including some that replaced what previously would have been locations.

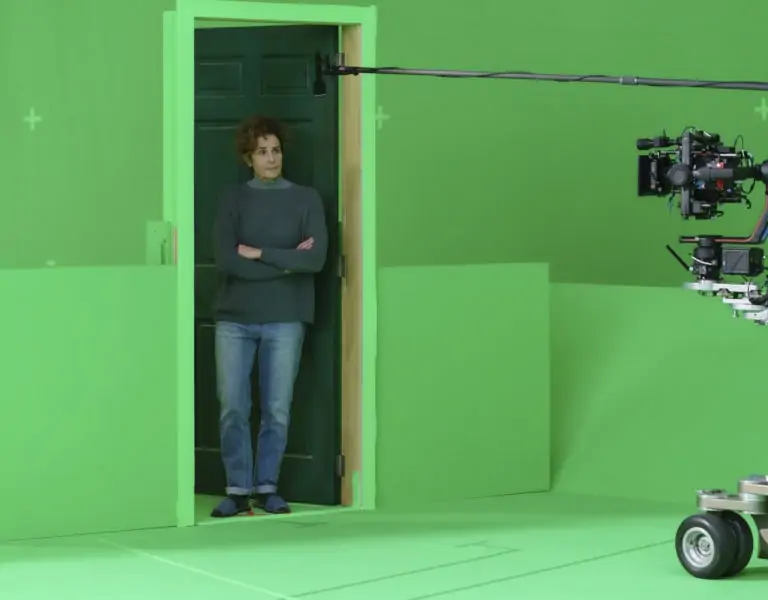

Shooting with “lens of choice” Cooke S4 lenses, affixed to ARRI Alexa Minis (supplemented with an occasional Angenieux Optimo 40mm Zoom), they also added a Scorpio 17-foot telescoping crane – the first one in the US – to the show’s toolbox. “It’s so compact. There are a lot of tight spaces you have to fit into (and) trying to get a crane into those situations was not a thing we’d do in previous seasons. It enabled us to do way more creative moving masters.” Plus, it helped with safety protocols, “having a camera arm that reached into the scene, so an operator wasn’t (always needed). That was a major addition to this season – that I’m hoping they’ll keep.”

Of course that season – and by all appearances, the show itself – will be concluding around the time this column hits the web. But whether another spinoff is spun, especially as Dr. Grey contemplates her own post-COVID life, remains to be seen. But as the good doctor considers that “going back to normal” after all these ordeals would mean nothing was learned from them, production – on this show, or anything else – won’t be the same either.

Whether that’s how they’re shot, how they’re distributed, how audiences encounter them, or even who currently owns the legacy brands that existed in “the before times.”

We’ll see you next after the Summer Solstice rolls around, with even more “for your consideration.” Until then, @TricksterInk, or AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com