Cinematographer Jack Donnelly discusses windowing DXL2 for 6K capture and pairing the camera with Super 35-format Primo lenses for Godfather of Harlem Season 2.

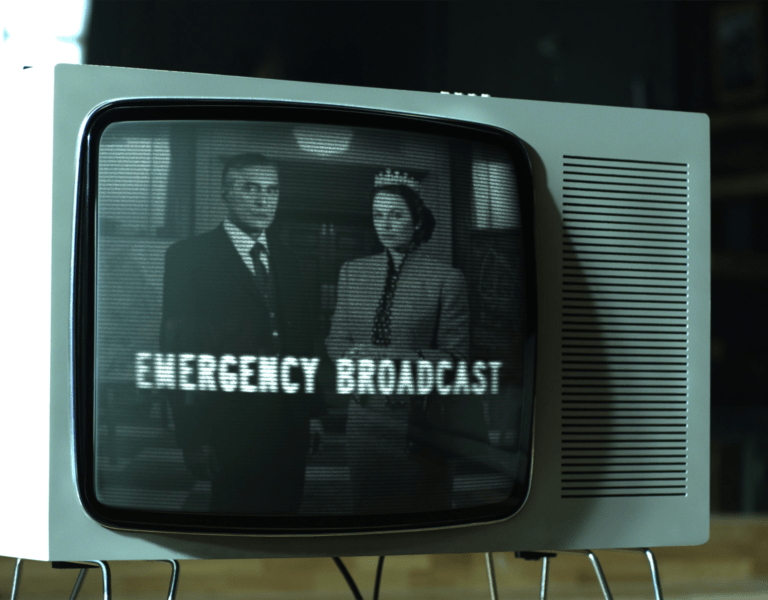

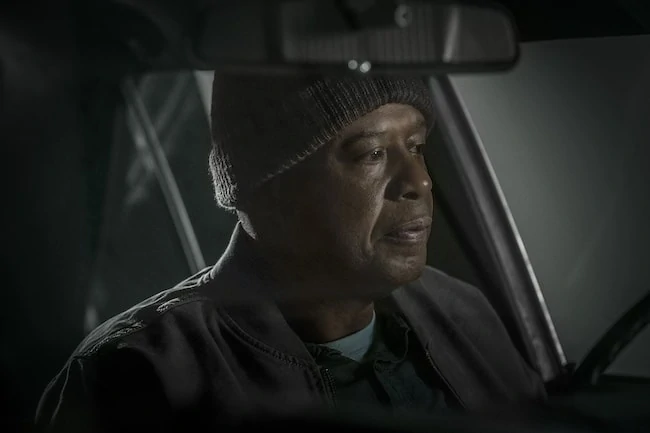

When Godfather of Harlem Season 2 begins, it’s February 1964, and the series’ eponymous gangster, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson (Forest Whitaker), has been in hiding for three months while notorious mafioso Vincent “Chin” Gigante (Vincent D’Onofrio) and his men scour New York City for him. Titled ‘The French Connection’, the season’s first episode opens with a disheveled-looking Bumpy driving headlong through nighttime streets with a carful of Chin’s thugs in hot pursuit. It’s a far cry from the powerful image Bumpy projected upon his return to Harlem after a stint in Alcatraz, but as he showed throughout Season 1, he’s endlessly resourceful, and one never knows what tricks he might have up his sleeve — or hidden in the trunk of his car.

Following his work on Episodes 2, 3, 6, 7 and 10 of Season 1, cinematographer Jack Donnelly returned for Godfather of Harlem’s second season, which continues to dance between fact and fiction as it weaves a narrative involving such historical figures as Johnson, Gigante, congressman Adam Clayton Powell (Giancarlo Esposito) and civil rights leader Malcolm X (Nigel Thatch). Donnelly was behind the camera for “The French Connection” as well as Episodes 4, 6, 8 and 10 of the second season. The remainder of Season 2 was photographed by Jay Feather.

“I knew Jay from when he was a 2nd AC,” Donnelly shares. “He used to second for me years ago, and we kept in touch as he moved up. He operated tandem days on different jobs that I was on, and then he moved up to being DP on Veep.” That production also afforded the two a chance to reconnect when Donnelly came aboard to shoot 2nd unit for episodes of Season 2 and 3.

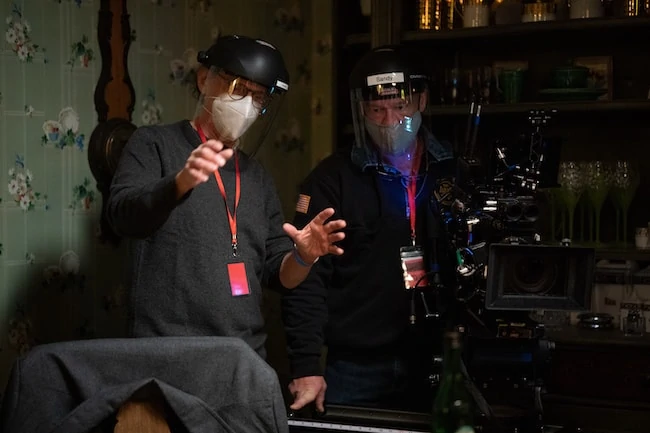

The cinematographers began preproduction for Godfather of Harlem’s second season in October 2020, with principal photography commencing in November and wrapping in April, just a couple of weeks before the season premiered on Epix on April 18. For Season 2, Donnelly brought the show to Panavision New York and elected to work with Millennium DXL2 cameras and Primo optics. “I’ve always been a Panavision guy, even when I was doing commercials back in the ’80s and ’90s,” he says. “When it was my choice this year, I wanted to go to Panavision for a number of reasons. I really like the DXL2 with its large Monstro sensor and the Panavision colour science, and I’ve always liked the Primo lenses.”

DXL2’s large-format 8K sensor can be windowed-down in-camera, with the 5K capture area matching a Super 35 gate. This allows the camera — in combination with field-swappable lens-mount adapters from the camera’s native SP70 to either PV35 or PL — to be paired with Super 35-format optics. “We actually went to 6K, and Panavision expanded a couple of the lenses on the wide end that needed it — the 14.5mm and 17.5mm,” Donnelly explains. “We only carried one full set of Primos, but I’d say 65 percent of the time we shot two cameras, so we would occasionally step down to 5K on one camera just to match sizes if we were cross-shooting — for example, with a 40mm and a 35mm, or a 50mm and a 40mm.”

Within the prime range, the 27mm and 35mm focal lengths proved to be particular workhorses for the production. “In coverage, we were often doing clean shots slightly off-eyeline with those lenses,” Donnelly says. “But we carried up to the 150mm, which made for good punctuation editorially.” Across the range of primes, the cinematographer tended to keep his exposure between T2 and T2.8, “but a lot of times I’d let it slide to full wide open,” he adds.

Despite the changes in camera and lens systems from Season 1 to 2, Donnelly says the filmmakers were focused on preserving “a consistent visual style” for the series. “I talked to [showrunner] Chris Brancato and [producing director] Joe Chappelle about wanting to keep pushing on the look we had started with Season 1, which was more or less wider lenses most of the time and covering scenes so we weren’t just doing over-the-shoulders to get closer eyelines. For important moments of dialogue, we would sometimes get the off-camera player to be almost behind the camera. With a wider lens, you feel a lot of the background even if it’s soft, which places the actor and makes it feel more personable.”

The visual consistencies also included a penchant for moving the camera on dollies and cranes — stable platforms that echo the grounded sense of command that Bumpy exudes. “Joe Chappelle [who directed ‘The French Connection’] specifically asked for that again,” Donnelly says. “So we used the wider lenses, and we moved the camera and the people around to make the scenes play out. That makes a big impact visually.

“We also used Steadicam a bit more this year, about 10 percent of the time,” the cinematographer continues. Handheld, too, had its place. For example, Donnelly says, “Later on in Season 2, there’s a bunch of handheld stuff with Chin” — who, in contrast with Bumpy, can seem dangerously unhinged. By limiting handheld to those specific story points that called for its particular energy, the technique “stands out more,” Donnelly says, which “makes it more effective for the viewer. It puts them in it.”

For both seasons, Donnelly’s key references have come from still photography of the early 1960s, including the work of Gordon Parks “and material from old magazines,” the cinematographer says. These references have helped the filmmakers recognise both period-accurate and anachronistic details when they’re working on location around New York City. “We find blocks in Harlem, in the Bronx and in parts of Brooklyn that look like Harlem would have looked from the second story up, but the retail floor and the street are all wrong,” Donnelly notes. “Even the crosswalks don’t look right. The art department will take down or change signage, and we’ll bring cars, trucks, telephone booths and garbage cans to block things.”

The visual-effects team, supervised by John Kilshaw, further helped transform modern-day New York into 1960s Harlem. Visual effects were mastered in 4K, which was among the factors that led to the decision to capture in 6K, as the extra resolution would allow for any necessary reframing or stabilisation.

The filmmakers also windowed the sensor to 5K or even 4K for higher-speed shots — for example, in a shootout sequence in Episode 8. There, the crew worked with the DXL2s at 96 fps, the maximum frame rate at 5K.

Regardless of the sensor area they used, the filmmakers could take advantage of DXL2’s 16 stops of dynamic range, 16-bit colour, and native 1600 ISO. “I used 1600 ISO about 30 percent of the time, but 800 was our common setting,” Donnelly explains. Knowing he could go to 1600, though, “did factor into our lighting approach,” he says. “We played setups on the dark side, knowing we had that additional stop of light if we needed it.

“It’s really a gangster show, so we made it dark,” the cinematographer continues. “That works with the storyline both narratively and emotionally, and it also helps us with the amount of 1964 that we have to make when we go out on location.”

The nighttime car chase that opens Season 2’s first episode offered one such opportunity for the production to leave the studio. In the sequence, as Bumpy tries to evade Chin’s thugs, the cars’ headlights shine straight down the barrel of the Primo lenses. “I like those lenses for their flares,” the cinematographer says. “Digital cameras often have flares from point sources like streetlights or headlights that look a little too electronic for me, but the Primos on the DXL2 worked well. I didn’t see any electronic pattern around those over-the-top highlights.”

Donnelly also made creative use of the Primos’ flare characteristics for a scene in a diner between Malcolm X and Bumpy’s daughter Elise (Antoinette Crowe-Legacy), who has found sanctuary within the Nation of Islam. Direct “sunlight” — actually a 10K positioned outside the set’s large front window — simultaneously frontlights Crowe-Legacy and backlights Thatch, flaring the lens for the latter’s coverage. “It made Elise look somewhat angelic, and I thought it kept a little bit of honesty in the light to have it behind Malcolm as he walked in,” Donnelly explains. “He almost gets wiped out by the flare, and then he takes it out once he’s seated. He’s at this moment in his life where he’s breaking away from the Nation of Islam, and I felt it visually added some interesting weight to the dialogue.”

Given Covid restrictions, Season 2’s location work was kept to a miminum. The creative use of flares added a suggestion of uncontrollable real-world elements to the production’s standing sets. “I knew I wanted to play with that through the season, especially being onstage,” Donnelly shares.

Over the course of ‘The French Connection’ Bumpy regains his position of power with the help of the prize stowed in his trunk during the episode’s opening car chase — a direct line to the Italian crime families’ European source of heroin. When the time is right, he steps out of hiding and pays a visit to the heads of the mob families (played by the likes of Paul Sorvino and Chazz Palminteri) who have gathered in a private restaurant. “I call it the Godfather scene,” Donnelly notes. “It’s a deeply coloured set, and we had an overhead source a la what Gordon Willis [ASC] had used for The Godfather. I really liked that scene — it’s got everybody in it, and they’re so great with each other. It was hard to get anything done, of course, because everybody was listening to them telling stories all the time!”

Shooting Season 2 during the pandemic, “there were times we needed a package for the next day, and there wasn’t enough time to get anybody from our crew over there, so Panavision had to prep it and send it, and they made it work,” Donnelly reflects. “There’s so much depth with Panavision. I know I can always source lenses and cameras for a tandem unit or whatever comes up at the last minute, which was especially helpful during Covid. The team in New York, including Sal Giarratano, Chris Konash and Chris Bieler, are like old friends. I felt secure, and that’s what I wanted. It was like going home.”

Published with permission from Panavision.