THE TRUTH SHALL PREVAIL

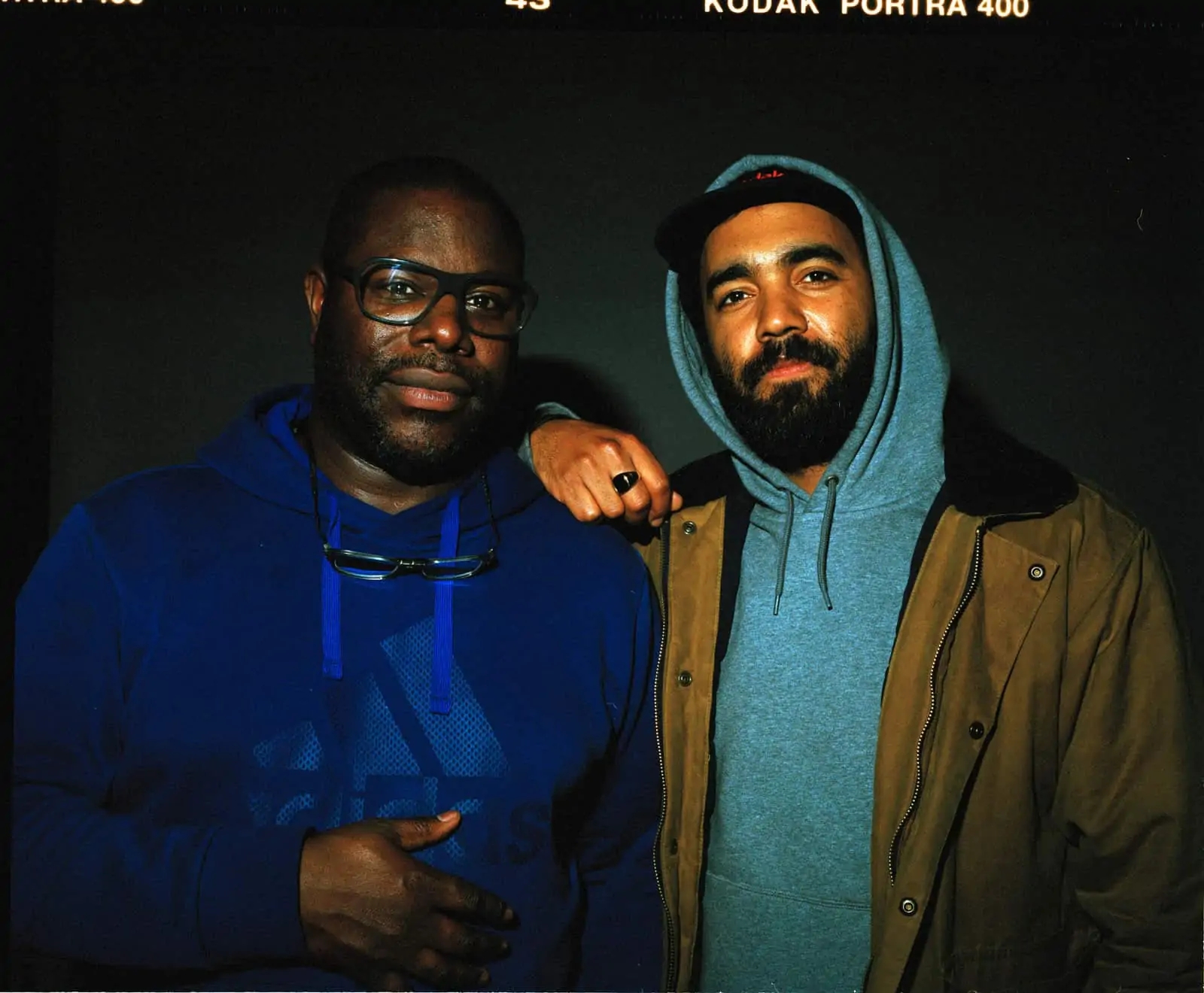

Mangrove – the first film in the monumental five-part Small Axe series unites cinematographer Shabier Kirchner with director Steve McQueen to tell personal stories of resilience and triumph that are both steeped in history and vibrant with culture.

“If watching Small Axe can inspire one youth in the Caribbean to become a cinematographer then that would be incredible,” director of photography Shabier Kirchner tells me during an interview which sees his belief in the power of film to create change shine through.

The theme of telling stories that inspire runs through the latest productions he lensed, Steve McQueen’s epic and ambitious five-film series Small Axe, which uses an assortment of creative techniques to tell compelling narratives of London’s West Indian community in the 1960s through to the 1980s.

The first film in the anthology, Mangrove, ties in with the 50th anniversary of the Mangrove March and tells the story of the landmark event which saw 150 black protesters organise a peaceful march in London’s Notting Hill against police harassment, racial discrimination and the unfair targeting of Frank Crichlow’s Mangrove Caribbean restaurant.

Mangrove also examines the 55-day trial in which the Mangrove Nine group of protesters – including Crichlow (Shaun Parkes), leader of the British Black Panther movement Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright) and activist Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby) – were wrongly arrested and charged with incitement to riot and affray and the challenges The Nine made to the fairness of the judicial process.

“It’s important for us to tell our stories or eventually we’ll lose our identity. Many people have not heard about the Mangrove Nine, but we all need to be aware of such a landmark case in British history,” says the native Antiguan cinematographer.

“The Small Axe series of films could be a significant flag in black cinema’s history. In Britain, the West Indian communities weren’t given the opportunity to tell their stories on the screen back in 1970 when the Mangrove case took place, so there’s a gap in cinematic history. Steve [McQueen] has given us the opportunity to remedy that and to get those stories out there.”

Kirchner’s involvement in the ambitious project was sparked when Sean Bobbitt BSC ASC, who lensed McQueen’s Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), asked to meet in New York.

“When my agent at Casarotto Ramsay told me Sean wanted to speak to me I was incredibly excited – he’s such a legendary filmmaker. When we met he told me Steve had been looking for a cinematographer to collaborate with on his latest project but hadn’t found quite the right fit. Sean said he would like me to have a conversation with Steve and a couple of days later we discussed the project and the script was shared with me.”

While reading Mangrove, Kirchner realised he had never seen West Indian voices and dialect quite like that on the page. “I was extremely moved by that,” he says. “I spoke to Steve again and told him how much the script resonated with me, especially when Altheia says ‘We mustn’t be victims, but protagonists in our own stories.’ Shortly after, Steve asked me to shoot the films.”

From the project’s inception McQueen told Kirchner to consider the productions as individual feature films rather than episodic television. This approach was welcomed by the DP, having come from an indie feature as opposed to a TV background, shooting films such as Skate Kitchen (2018) and Bull (2019).

“My head was already geared towards finding the individual identity of each script. We looked at each one as its own story, knowing they would be joined together by the fabric of black culture in London. If we looked at the project in its entirety and tried to figure everything out for five films in advance, it would have been a daunting task for me, so we approached each separately, starting with Mangrove.”

Many of the Mangrove families are still alive and some of them actually came on set during filming and we wanted it to feel as authentic as possible.

Shabier Kirchner

Early conversations about how to create a realistic world for the story to unfold within were grounded in history, which led the production team to examine archive footage and photographic material. The production office walls were plastered with photographs from the era in which the events took place and of the Mangrove Nine inside the Mangrove restaurant and in the streets of Notting Hill.

“Production designer Helen Scott’s team and the researchers did such a fantastic job compiling all this information,” says Kirchner. “Many of the Mangrove families are still alive and some of them actually came on set during filming and we wanted it to feel as authentic as possible.”

When the audience is first introduced to the Mangrove, it is brand-new, and the colours are warm, rich and fresh. As time passes and the restaurant experiences stress and fractures due to the police raids, the colours are gradually muted and diluted.

“While planning the aesthetics of the early scenes we were aware the focus would then need to switch to the inside of the courtroom – a completely different universe to the Mangrove. Helen was so thorough in her design and her choice of colours for every stage of this story,” says the DP.

The plethora of visual material gathered informed conversations about the overall feel of the production. “We tried to consider what Mangrove would have felt like if it were made in 1975. How should we honour a film of that era that didn’t get the chance to be made? We were not just trying to rewrite history, we were just trying to write ourselves into it because we’d been left out for so long,” says the cinematographer.

Discussions first explored texture and patina before the option of shooting on 35mm film was considered. “We knew we wanted it to feel like photographs of the era and to be reminiscent of the colours and feeling of Gordon Parks’ documentary photojournalism. We decided that 2-perf Kodak 35mm film would work well because of the structure and grain it inherently offers.”

What the Mangrove Nine represented – challenging the system as a community to ensure justice was served – also influenced the creative decisions. “This was the way we wanted to frame the nine characters – as a community. We knew there would be many characters in one frame, the community versus the system, which a 2.35:1 aspect ratio would allow us to do,” says Kirchner.

After a six-week prep period, principal photography for the first of the Small Axe films began in June 2019, lasting three weeks. Each of the five films was shot in a similar timeframe. At the start of filming, Mangrove was intended to be split into two films, the latter focusing on the trial. Halfway through shooting, McQueen decided combining it into one film was a more appropriate and rounded way to tell the story.

The director was clear the production would be completely location-based and wanted the outside and inside world – the characters from the Mangrove – to interact. Many of the exterior Notting Hill scenes were filmed in Kentish Town, Camden and Kilburn, with the majority of the protest scenes shot in Deptford.

“It was all about how to build a periphery for that community. Scouting locations that still featured remnants of the past was difficult, but our team found the perfect street in Kilburn that resembled All Saints Road in Notting Hill. They dressed the whole block to make sure the storefronts and buildings were true to the era,” says Kirchner.

The Mangrove restaurant was reimagined in offices which were gutted and transformed into an environment that was evocative of the ‘70s. The Old Bailey was used for textural shots of the court and scene-setting shots of elements such as the ornate ceiling, while Kings Court in London was chosen as the filming location for scenes inside the courtroom and jail cells. “When shooting in the Old Bailey it was terrifying to know that is where the worst of the worst get tried and the Mangrove Nine names were wrongly included in that,” says Kirchner.

An effortless approach

On set, McQueen would often reference the filmmaking philosophy of one of his collaborators and friends, the late, great Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller. “As Robby would tell Steve, ‘Whatever you do needs to seem as effortless as a cat jumping on a table.’ That idea really stayed with me. If I couldn’t figure something out, or if it became too overbearing, we just pulled it back to simplicity,” says Kirchner. He also took inspiration from the work of Müller, including his incredible book of polaroid photographs and films such as Paris, Texas and The American Friend as well as the films he made with director Jim Jarmusch such as Stranger Than Paradise. Robby was also born in the Caribbean island of Curaçaol; I think I can feel that in his work.”

When the decision to shoot on 35mm was made, Kirchner knew he wanted to work with the ARRI Arricam LT. As the cinematographer would also be operating on the single-camera production, he wanted a camera he was familiar with and that offered a comfortable and functional eyepiece.

“I’ve always been a huge fan of the Arricam LT – I think it is one of the sturdiest, most reliable cameras ever built. The Arricam LT feels great on the shoulder and is very adaptable to being on a dolly or crane. We also used an Arriflex 235 lightweight 35mm camera for some handheld shots and scenes within tighter spaces,” says Kirchner. He also added a personal touch and engaged the whole production team with the culture being explored by printing out different Caribbean flags to display on the camera magazines.

After in-depth lens tests Kirchner opted for the Cooke Speed Panchro S2, using the Cooke S4 for certain wide shots and VFX shots: “Cooke glass is fantastic – it worked extremely well for building the world of the Mangrove and the roll off on the skin tone feels so smooth.”

Kodak Vision3 500T film was selected for the majority of Mangrove, with certain VFX shots filmed on 200T as “it offered a slightly cleaner result.” Kirchner pushed almost all scenes by one stop, sometimes two. “I wanted to add more richness, saturation, grain and texture to the image without cooking the darker area of the image too much,” he elaborates.

“Films of that era also featured levels of imperfection which make them unique and beautiful to revisit. Nowadays you can do almost anything thanks to technological advances – everything can be so perfect, slick and pristine that it can lose a lot of that character. We wanted to approach Mangrove another way; it needed to feel handmade, which required a different approach to exposing, manoeuvring the camera, and lighting.”

For instance, in the final courtroom scene, a crane shot is used to whip across the room as the judge enters before it settles on the dock and finally on Frank Crichlow’s face. “When we smoothed all of that out, it felt too perfect,” says Kirchner. “Keeping some camera wobble was important – imperfections are perfections. We used a zoom lens to zoom in a more stop-and-start fashion rather than a smooth transition which made the scene feel more human and of the era.”

Steve’s very much an actor’s director – you don’t adjust the actor for the shot; we figure out a way to make a shot work for us around the actor.

Shabier Kirchner

Although the protest sequence was mapped out and designed early on, Kirchner and McQueen did not want it to be too structured and so allowed the scene some freedom to naturally evolve.

“We used a 50-foot Technocrane for a top down shot of one of the first protest sequences and as we filmed, it started to rain. Steve said the shot just didn’t feel right, so he devised a different approach – to get into the mix and stick with each of the main characters, staying at arm’s length the whole time. That was it – we knew that Altheia, Frank, Darcus and Barbara Beese (Rochenda Sandall) would be our hero characters within that,” says Kirchner.

Archive footage of the peaceful parts of the protest, before the police got involved, was useful reference material in prep, but once the action began unravelling during the shoot, remaining close to the key characters was imperative to the scene’s success.

“Steve’s very much an actor’s director – you don’t adjust the actor for the shot; we figure out a way to make a shot work for us around the actor. For this scene we wanted to hear the inflection of their voice and feel the sweat. I got knocked about quite a lot when shooting and at one point a piece of wood hit me on the back of the head and fell to my knees, but swiftly got back up again. It was all about getting amongst the action – it felt a lot like documentary filmmaking.”

Devising new techniques

Mangrove was filmed in reverse order, with the trial shot first, followed by the exterior scenes in the street and then the Mangrove restaurant interiors. New techniques were devised for the courtroom scenes to expand the creative storytelling options.

“Filming in a real courtroom meant we couldn’t move any benches; it was all locked in and very tight. I’m used to seeing American courtroom dramas where there’s a lot of space and it’s very theatrical – the prosecutor walks towards the jury and then back towards the judge and to the crowd. In the UK everyone is locked in their position and there isn’t a lot of walking space,” he says.

The courtroom was also arranged on multiple levels, with defendants down low, the jury in a dock six feet off the ground, and the press and judge above them. This posed an interesting challenge to Kirchner when manoeuvring the camera.

“We didn’t have time to keep building platforms,” says Kirchner. “Through discussions with key grip Adrian Barry we figured out the most effective solution would be to keep the camera on a remote head on a crane, with me operating from another room. I wasn’t on the eyepiece for the first two weeks.

“Adrian figured out it would be possible to break down the Scorpio EZ head with the Fisher 23 arm and rebuild it in a longer length in under six minutes. A telescopic arm couldn’t have manoeuvred that space as fluidly and it would have taken longer because it’s a lot larger and heavier.”

Many of the technical solutions the team devised to efficiently manoeuvre the camera informed creative decisions. “In another courtroom scene, when Darcus cross examines PC Pulley, we came up with a solution in the moment, using that same set up of the crane, jib and camera on a remote head to swing around him, which we couldn’t do using Steadicam, handheld, a dolly or slider. As Steve always says, ‘limitations are freedom,’ and I agree with that.”

Restrictions that limited camera movement in the courtroom scenes had a similar impact on lighting the space. Kirchner wanted to use changing light to convey the passage of time during the mammoth 55-day trial.

“Ian Glenister and our spark team built an amazing rig and massive platforms outside each of the three large windows on either side of the court room to elevate six Alpha 18K lamps,” says Kirchner.

The scenes in the Mangrove restaurant were the most challenging to light due to the low, fixed ceiling and inability to fly the wall out. The set constraints and number of people and dollies in the space also made manoeuvring the camera difficult.

The initial intention was to avoid LED fixtures because it was not authentic of the era in which the events took place, but it soon became clear this would be difficult to realise. “Lightmat make an excellent series of tile lights that are super thin, draw little power and could be Velcroed to the ceiling. In front of that we put thick, off-coloured cloth and leaf green, steel green or yellow gels to break up the electronic feel of the LED. We coupled that with wall sconce lighting of the period such as tungsten bulbs, used the LEDs on top to give us a base light and put a skirt around it to prevent spill,” explains Kirchner.

The vibrancy of Gordon Parks’ photograph of a street corner in New York, taken from a passing car, inspired the approach to lighting the night-time scenes in the street outside the Mangrove restaurant. Unable to climb on the pointed roofs, the lighting team rigged eight Source Four lamps outside the windows of top-floor apartments to create a base layer of light.

“These were gelled blue green to mimic the silver allied Mercury vapour lights of that era and pointed down from bedroom windows, with our team guarding and dimming them or moving them to spotlight certain areas,” adds the DP.

Realistic beauty

Paul Dean, head of grading at Cinelab London, was brought on board as dailies grader for Mangrove, providing 1080P Baselight scans. “This got us in a good place to view the rushes for Steve to start editing with,” says Kirchner. “I would mainly check to make sure everything was technically focused and exposed correctly, but I didn’t look at the dailies too extensively because I didn’t want to be distracted every day and second-guess myself.”

Lipsync Post completed the final 2K scans on an Arriscan before the final grade was carried out by colourist Tom Poole of Company 3, who has worked on all McQueen’s films, including Widows and Oscar-winner 12 Years a Slave.

“We worked to find a grade that was complementary to each story without feeling affected or forced,” says Poole, who, like McQueen, is also a fan of the look and feel of images photographed on celluloid.

Once the negative was scanned, Poole applied a print emulation LUT to the digital files, with “restricted whites, nice roll-off, and halated whites that you get from a film print.” Having sought inspiration from 1970s photography, the filmmakers endeavoured to capture that look in the final imagery as opposed to a more “retro” interpretation.

“We wanted that oxblood red, the true tonality and the deep blues and teals, almost as if we’d found an unprocessed role of Kodachrome or Ektachrome from the period, processed it and made film print out of it,” says Kirchner.

When Poole is grading for the type of filmic look McQueen embraces, he likes to begin by using Resolve’s Offset tool, which alters the image in a similar way to photochemical colour timers, brightening or darkening and augmenting colour globally, without changing the curve or introducing any secondary corrections. The parameters are limited compared to what is possible using Lift, Gamma, and Gain and introducing secondary corrections. Nothing is augmented in the first pass in a way that hints at digital manipulation.

“When the images are balanced and I am as close as I can get to where we want to be, I use Lift, Gamma and Gain to finesse everything,” says Poole. “Rather than go heavily into secondaries straight away, the trick is to get as much as you can done as simply as possible. That is not to say we didn’t shape or augment anything in the grade, but we were always mindful of realistic beauty. When something is too heavily graded the viewer can become hyper-aware they’re watching a narrative and can become somewhat disconnected from the reality of the situation.”

Kirchner shot with tungsten-balanced stock and allowed tungsten, fluorescent and daylight to exist together, particularly within the Mangrove restaurant to create mixed colour palettes. The space, Poole says, “was bathed in tungsten lights with warm lampshades that read as a beautiful honey gold, but fluorescent fixtures and daylight were also coming in – Shabier let the different kinds of light mix in beautiful ways.”

In counterpoint, the trial scenes were a much cooler colour temperature as a result of not being shot with a corrective filter and from the light shining through the windows. “We pulled those a bit more towards neutral in the grade, but the palette still plays against the warm tungsten look of the Mangrove,” adds Poole.

The collaborators further augmented the look of daylight from sequence to sequence to convey a sense of slightly different natural light coming through windows from day to day to help convey the length of the trial. “We’d make it a little cooler one day, overcast another or a bit brighter in the morning than late in the day,” notes the colourist.

Kirchner, who had not seen much of the footage until Poole presented his first pass on final grade, refers to being introduced to it as a “rebirth.” “Having only checked the technical aspects of the dailies his pass was mind-blowing and what he achieved was so beautiful,” says the cinematographer. “We spoke about Gordon Parks’ photography and a Bob Mazzer photograph of the London Underground and Tom just got it and created a beautiful Kodachrome look.”

Belief in the truth

The Small Axe anthology was shot on multiple formats: 3-perf 35mm for true story Red, White, and Blue which explores racism in the London’s police force; large-format Sony Venice for biopic Alex Wheatle about the writer’s life and experiences surrounding the Brixton Uprising of 1981, 16mm film for 1970’s story of educational segregation Education; and ARRI Alexa Mini for Lovers Rock, an ‘80s-set love story unfolding over a single evening at a blues party.

Kirchner did not begin the project thinking he would use five different formats. “It was just how it evolved,” he says. “We spoke about the visual approach for Mangrove just before we shot it and then we discussed Lovers Rock’s look and feel before shooting that and so on. I was still immersed in Lovers Rock and Alex Wheatle before I had read the final draft of Red, White and Blue.”

Format decisions were based on the stories and the way McQueen wanted to tell each one. “For example, he wanted Lovers Rock to feel quite contemporary and to convey the love and joy of an ‘80s black house party, unlike the way in which Mangrove was a homage to the early ‘70s era. We also knew Lovers Rock would be shot handheld and the camera package we felt would fit that best, be light enough to manoeuvre easily and offer a clean and slick image was the Alexa Mini with Master Primes.”

The decision to shoot Education on 16mm film was a personal one and happened quite shortly before shooting began. “The BBC was cautious about us shooting on 16mm because nobody had shot on 16mm for BBC transmission for around 20 years, but there’s something about the grain that feels so alive and personal and Steve wanted to pursue it. When he grew up, around the time Education was set, filmmakers such as Alan Clarke and Ken Loach were making 16mm films. Steve wanted to pay homage to that era of filmmaking and imagine what it might have looked like if a filmmaker from the communitiy was telling this story through film at that point in time,” says Kirchner.

“The Small Axe films are very specific stories and I think my West Indian heritage formed a big part of my working relationship with Steve. He puts a lot of trust in you and really empowered me and everybody on set to be present in the moment. It was also always about the truth, believing that we were telling that important truth in Mangrove. Steve really is one of the greatest artists living and I can’t thank him enough for giving me this opportunity.”

The Small Axe films are available via the BBC iPlayer in the UK and on Amazon Prime in the US. Shabier Kirchner is represented by Casarotto Ramsay.