Against the tide

Philippe Ros AFC / Océans

Against the tide

Philippe Ros AFC / Océans

Capturing marine life across 54 countries in three and a half years with the aim “to be in phase with the animals, a dolphin among dolphins”, Océans is an ecological drama/documentary.

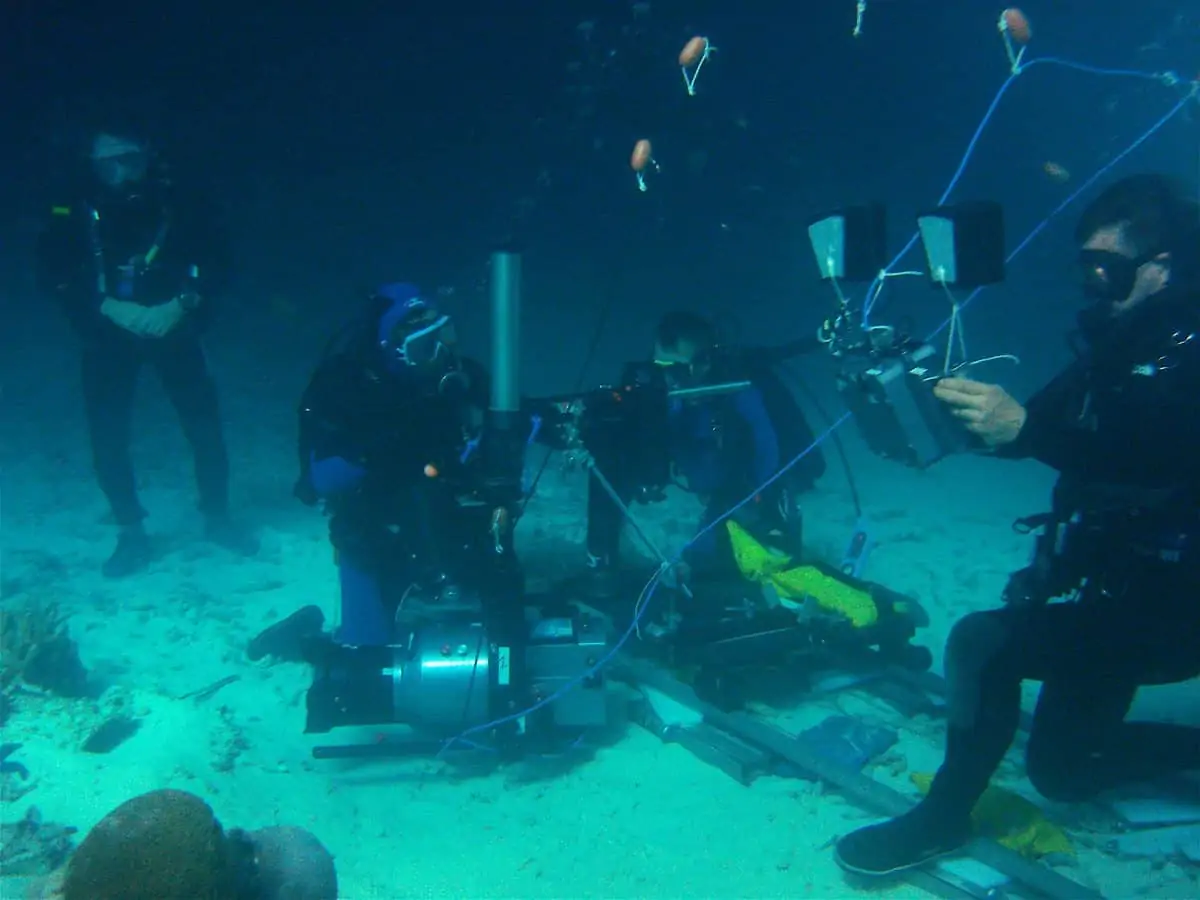

The film boasts incredible shots topside by Luc Drion SBC, Christophe Pottier, Laurent Charbonnier and underwater by cinematographers Didier Noirot, René Heuzey, David Reichert and Yasushi Okumura.

For the film’s digital imaging director, Philippe Ros AFC, sourcing and customising the right cameras and pulling all the footage together from each DP to create a workflow for such an epic production were the main tasks.

While this article focuses on his challenges only, Ros is at pains to explain that his role was one of many, and he adds that some of the DPs involved in the production risked their lives to capture astonishing aerial and underwater shots never before captured on camera.

Ros’s past work has included customising 35mm cinemascope motorbike cameras for the Tour De France, and it was his ability to find the right tools and workflow for a production that brought him to the attention of two French directors Jacques Perrin and Jacques Cluzard back in 2003.

“They talked about dealing with an underwater world and an Imax release… so I knew very early on that I would need to start with the exhibition requirements and work backwards,” says Ros.

Ros was given a total of nine months to prepare for the project, before shooting started back in 2005. According to Ros, the directors were a little surprised when he told them that the most important person on their project was going to be the colourist.

“They felt it was a bit like swimming against the tide,” Ros recalls, “but I knew that if the post production was sorted out it would save time later,” he says, adding that the film’s executive producer, Olli Barbé of Galatée Films played a key role in supporting Ros’s vision, driving the project “into the digital world”.

Ros’s main concern was that he knew that all of the underwater footage would have to be shot digitally and a big challenge was going to be how this would look blown up on an IMAX print.

Another challenge would be finding a way to seamlessly match up digital footage with 35mm. A direct line of communication between the underwater cameramen and the colourist therefore, would need to be set up early on in the production.

With these factors in mind Ros assessed his camera options. The directors were keen to use film, and 35mm is used in all above sea shots and slow motion sequences, but Ros had to persuade them that for underwater sequences digital cameras would be a better choice. “While they could see the time benefits for shooting digital they didn’t like the common ‘video’ look,” he explains.

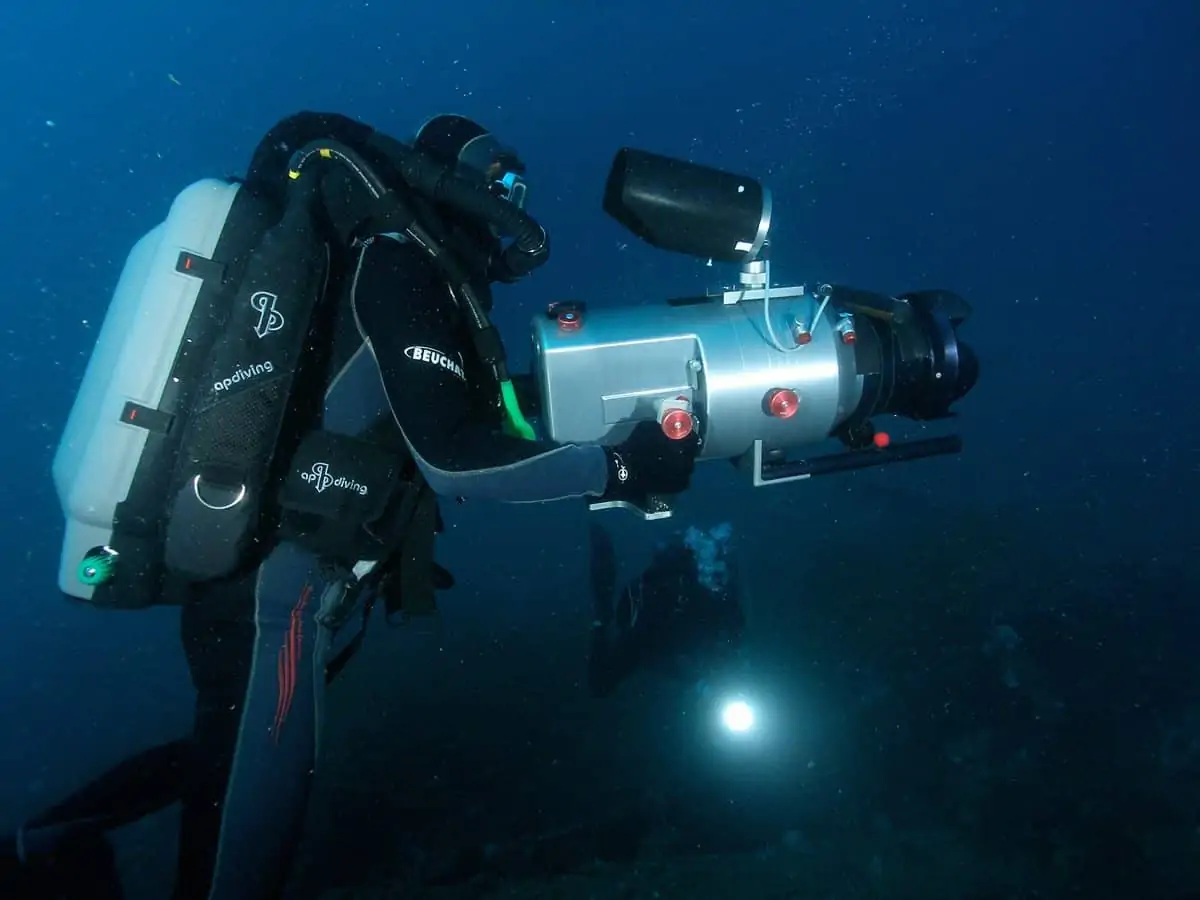

According to Ros, compromises had to be made considering three elements: size, weight and quality. “We chose Sony’s HDW-F900 because it was able to give the underwater filming team 48 minutes of uninterrupted filming time (as opposed to six minutes at a time on film in 3-perf).

“The camera and u/w housing also weighed under the maximum weight we’d set ourselves of 40kgs and the 900/3 version allowed us to create our own user gamma curves.”

"The solution to have a lighting continuity between natural reef and tanks, was to use a floating culcoloris – a frame with holes in it designed to create a ‘moonlight effect’ from lamps that were positioned remotely."

- Philippe Ros AFC

Ros adds that he knew the ability to create gamma curves, introduced by Sony in 2004 just before the film went into pre-production, would be the solution to matching up the 35mm by allowing him to increase the dynamic range of the video footage and suppress the video look - a process known as solarisation.

“With Olivier Garcia from HDSystems and Christian Mourier, Sony engineer and creator of the Hypergammas, we designed a gamma curve trying to imitate film stock after scanning making it easier to match. With digital, an image’s highlights are clipped, there’s not much detail so we designed a curve to soften the highlights,” he explains, adding that this approach gives the colourist much more flexibility in post.

Underwater camera operators were given housed cameras with a choice of gammas and settings, which were linked to visibility and how deep they were shooting.

As Ros points out: “Blue sea at 10-25m might be very different from blue sea at 0-10m.”

The DPs were also asked to check back at the hotel each section of footage they worked on - detailing their choice of settings and reasons for taking them. These were then added to the camera’s memory – with a total of 25 different choices recorded overall. Ros called these choices “digital stocks”.

These online shooting reports were sent to the postproduction and editing rooms allowing Ros and the colourists to scope, note and, where possible, correct any potential problems during the production stage.

In addition to devising the workflow, Ros also worked as a DP for the underwater night shoots where his main challenge was to simulate a realistic nighttime set to track crabs and very small sea creatures in and among a natural coral reef off New Caledonia.

“It was impossible to film all the close up sequences on location because it would have been impossible to follow some little animals. The solution to have a lighting continuity between natural reef and tanks, was to use a floating culcoloris – a frame with holes in it designed to create a ‘moonlight effect’ from lamps that were positioned remotely,” he explains.

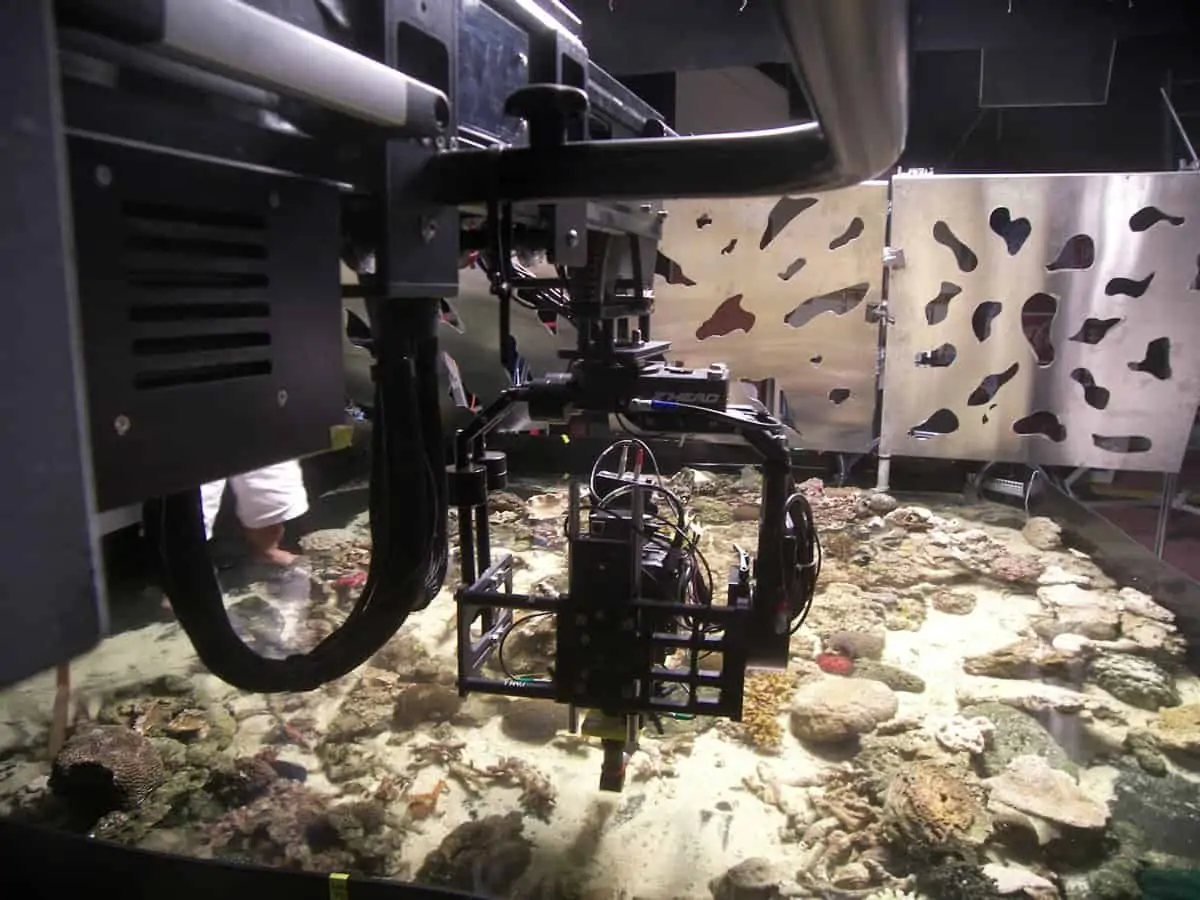

Establishing shots were taken in New Caledonia and then these scenes were later recreated for medium and close up shots in an Australian tank where a coral reef has been created 20 years ago and a 25cm deep tank created in the Australian studio of marine biologist and cinematographer Richard Fitzpatrick.

Two moving aluminium culcoloris were placed between the tank and the lamps to recreate the same lighting effect (devised by gaffer Paul Johnstone) while a cooling system was also used to cool the water temperature, which, thanks to the lighting, often reached 50 degrees.

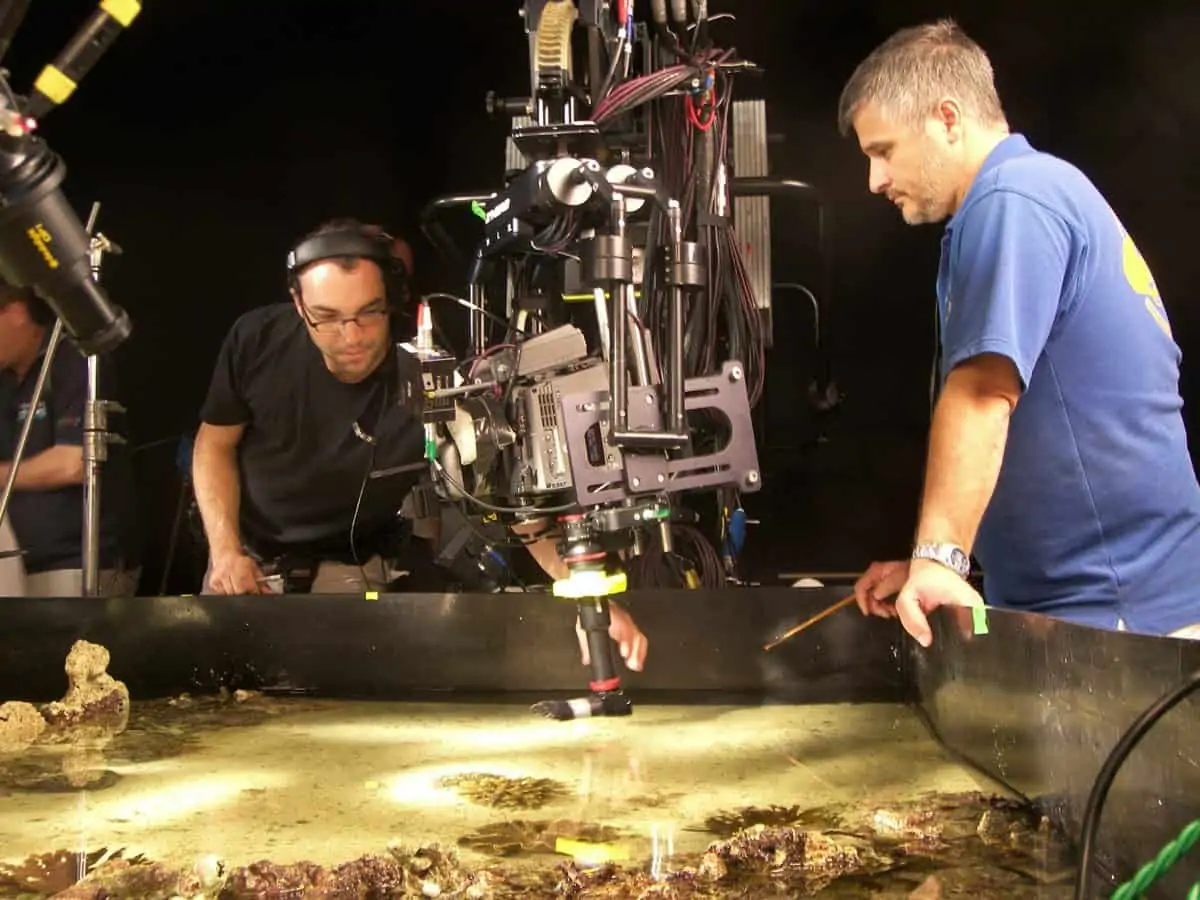

Inside the tank, in and among the coral, creatures were tracked and followed using a special crane developed by Louma Systems. The crane has a telescopic arm with a digital F23 camera and an underwater Innovision Prob lens attached to it, with the lens immersed in the water. Once again, Ros assured that the gamma curve in the camera was adapted to the lighting and the set.

According to Ros, some of the animals caught on camera were only 2cm tall, and can be seen swimming at great speed in and out of the rocks. Ros also managed to capture, in all its glorious detail, a crab being wiped out by a shrimp-like creature called a Manta Squille.

Even smaller creatures were caught on camera thanks to a system called Microscope developed in conjunction with Hervé Theys, an engineer at Hdsystems. The system consists of a Sony F23 camera attached to one channel of a Zeiss stereo microscope placed on a set of cranks, which is able to shoot move around a table and zoom in and track tiny microscopic organisms of just 50 microns in length.

“I was able to catch footage of a Lobster egg as well as the eye of a young lobster and Olivier Garcia from HDSystem designed gamma curves to save all the highlights,” says Ros.

The Microscope also allowed Ros to light a single drop of water for an end sequence, which forms an important part of the film’s narrative device.

Ros spent many hours after the shoot with the grading’s art supervisor, Luciano Tovoli AIC ASC, on the 17 weeks of grading that Océans required. Ros was able to pass on his knowledge of every shot and decision taken thanks to the detailed online shooting reports he had compiled with the help of his underwater crew.

After the grade Ros also attended a five-day session of with colourist Laurent Desbrueres at post production house CMC-Digimage Cinema. The main challenge was to match up the grain of film materials with the HD footage, harmonise the noise level of digital materials, and defocus and refocus shots to match up the sharpness of the video material with the 35mm footage.

Ros is proud to add that of the 960 shots chosen by the directors and editor, only four proved to be a poor match. He says: “Océans' production set up gave us more freedom to work with the colour grading. When the audience watches the film, never for a second will they wonder about the origin of its footage.”