Encore Performance

Wally Pfister ASC / Inception

Encore Performance

Wally Pfister ASC / Inception

Christopher Nolan, Wally Pfister ASC and producer Emma Thomas have collaborated on the creation of another breathtaking motion picture. Inception follows in the wake of Memento, Insomnia, Batman Begins, The Prestige and The Dark Knight. The Warner Bros. film revolves around Dom Cobb, a criminal mastermind who has invented a way to invade people’s dreams and steal their most precious secrets, writes Bob Fisher.

Nolan cast Leonardo DiCaprio in the leading role, and had long discussions with the actor, whom he credits with contributing important ideas for using his character’s feelings as a way to pull audiences deeper into the story on an emotional level. The star-studded cast includes Ken Watanabe, Marion Cotillard, Ellen Page, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Cillian Murphy, Tom Berenger, Tom Hardy and Michael Caine. Describing it as an ambitious endeavour is a considerable understatement.

Scenes were filmed in Japan, Morocco, France, Canada, the United States and England. They range from strolls down city streets to a breathtaking ride on skis down a snow covered slope and surrealistic journeys inside of dreams.

“We can do amazing things on a set pretending to be in Morocco,” Emma Thomas says, “but the energy feels different when we are shooting at real locations. There is something almost indescribable.”

Dream sequences were filmed on sets at Cardington Studio, including the former zeppelin hangar where scenes for Batman Begins and The Dark Knight were produced. Gaffer Cory Geryak and first assistant Bob Hall, who are longtime collaborators, travelled to all locations with Pfister.

Format and kit

Nolan and Pfister discussed producing Inception in the 65mm IMAX format they used while filming The Dark Knight, however they agreed that would have been impractical, because of the many “runaround” handheld shots envisioned. The visual grammar they created was produced with a blend of shots in 65mm and 35mm anamorphic formats augmented with VistaVision aerial images. They also used a Photosonics camera to record ultra-slow motion images for dream scenes.

The camera package provided by Panavision included 35mm Panaflex MXL and ARRI 235 bodies, with a complete set of anamorphic lenses, Panaflex 65 mm Studio and Spinning Mirror bodies, and a full range of lenses. Pfister had Kodak Vision 3 500T 5219 negative on his palette for night and interior scenes, and Vision 3 250D 5207 and Vision 2 50D 5201 for daylight exteriors.

He and Nolan generally covered scenes with a single camera. The exception to that rule were action sequences where two or more cameras provided coverage from different perspectives. Pfister is a former news cameraman who generally does his own handheld shots. He made certain the cast knew he had their interests at heart.

“Wally and I really started to hit it off when we started talking about music,” Gordon-Levitt says. “He’s a great guitarist. He brought me to a blues bar in England where he played the guitar and I backed him up on drums. You can see his musicianship in his camera work. His use of a handheld camera was almost like having another character in scenes. … You can feel the movement link with his timing and rhythm.”

"Chris said a 10 mintute dream can feel like it's a day long while you are experiencing it."

- Wally Pfister

Other scenes were filmed with cameras on a Steadicam and a Technocrane. Shots filmed in 65mm format ranged from crowd scenes on city streets to an intimate sequence where a character is visiting his dying father. The higher resolution images are like a magnet that draws the audience into the emotions of that sequence.

Aerial scenes were filmed in VistaVision format, which Paramount Pictures used to produce The Rose Tattoo and other motion pictures during the 1950s. Images are recorded on 35mm film that is eight rather than four perforations long, and the film runs horizontally through the camera. Pfister explains that the higher resolution images “jump off the screen, and give added clarity to shots with intricate details.”

They filmed slow-motion sequences with a Photosonics camera, frequently at 1,000 or more frames per second. The camera was initially used during the 1960s and ‘70s as a tool for photo instrumentation applications, ranging from studying the dynamics of how machines work to documenting launchings of NASA space vehicles.

Inside dreams

Nolan says that the idea for a story about what happens inside of dreams has been percolating in his fertile imagination since he was 16 years old.

“I read a script for Inception sometime after we made Insomnia (2002),” Thomas recalls. “Chris had only written 80 pages. Either the timing wasn’t right or Chris didn’t feel that he had gotten the story to the place he wanted. We went on to other projects. After we finished The Dark Knight (2008), Chris and I were talking about what should come next. He pulled the 80 pages out of the drawer, and said, I think it will work.”

Nolan gave Pfister the script for Inception to read in February, 2009. “I was blown away,” Pfister recalls. “It had a lot of emotion packed into it. In our first discussion, I asked Chris how he wanted audiences to see dreams on the screen. He said that he wanted them to feel real with an enhanced sense of time. Chris said that a 10-minute dream can feel like it’s a day long while you are experiencing it. The slow-motion imagery helps to create an existential feeling.”

Pfister visited locations that scouts found in the various cities. They ranged from a helipad on a rooftop in Tokyo to city streets in Paris and Morocco and the ski slope in Canada. After visiting the latter location, Pfister recruited cinematographer Chris Patterson who has specialised in shooting skiing films for 18 years. “Chris has mastered the art of shooting handheld shots while skiing,” he says.

Dream sequences filmed in Los Angeles include one at a vertical lift bridge which links the harbour to an island. While the bridge is rising to allow a ship to sail under it, a van crashes through a barrier and falls off the edge of the bridge into the ocean. The shot of the car falling off the edge of the bridge into the ocean was filmed in slow motion.

The production team spent about two months shooting scenes in London, mainly on sets at Cardington Studio and in a former zeppelin hangar.

"He pulled the 80 pages out of the drawer, and said, I think it will work."

- Emma Thomas

Physical effects

“(Special effects supervisor) Chris Corbould played a crucial role in the design of sets used for physical effects shots,” Pfister says. “One set was an elevator shaft where an explosion is followed by a ball of fire coming up from the bottom in slow motion.”

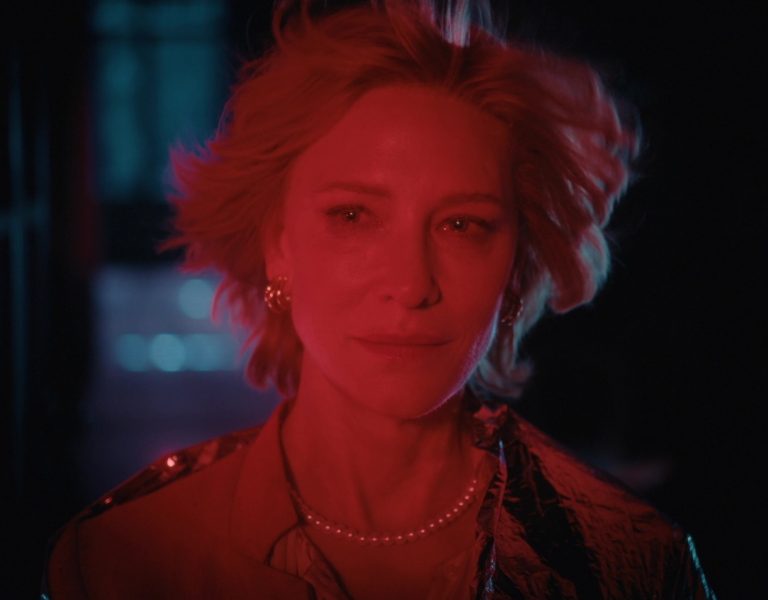

Another set is a nightclub where Cobb is telling Fischer (played by Murphy) that they are inside a dream where he controls what happens. As Cobb stands up, the light coming through a window shifts from a warm sunset to a cool, dark cloudy look while the nightclub begins to tilt at a 30-degree angle. Pfister explains that it is a non-verbal way of telling the audience they are witnessing a dream.

“We used a 20K with double CTS filters outside a window on the set to create an orange sunset look,” Pfister says. “We used diffusion to darken the light as the set tilted and glasses and plates began sliding off the bar and tables.”

He makes it sound simple, but his collaboration with the gaffer and effects team is a subtle way of telling the audience they are witnessing Cobb spying on a dream.

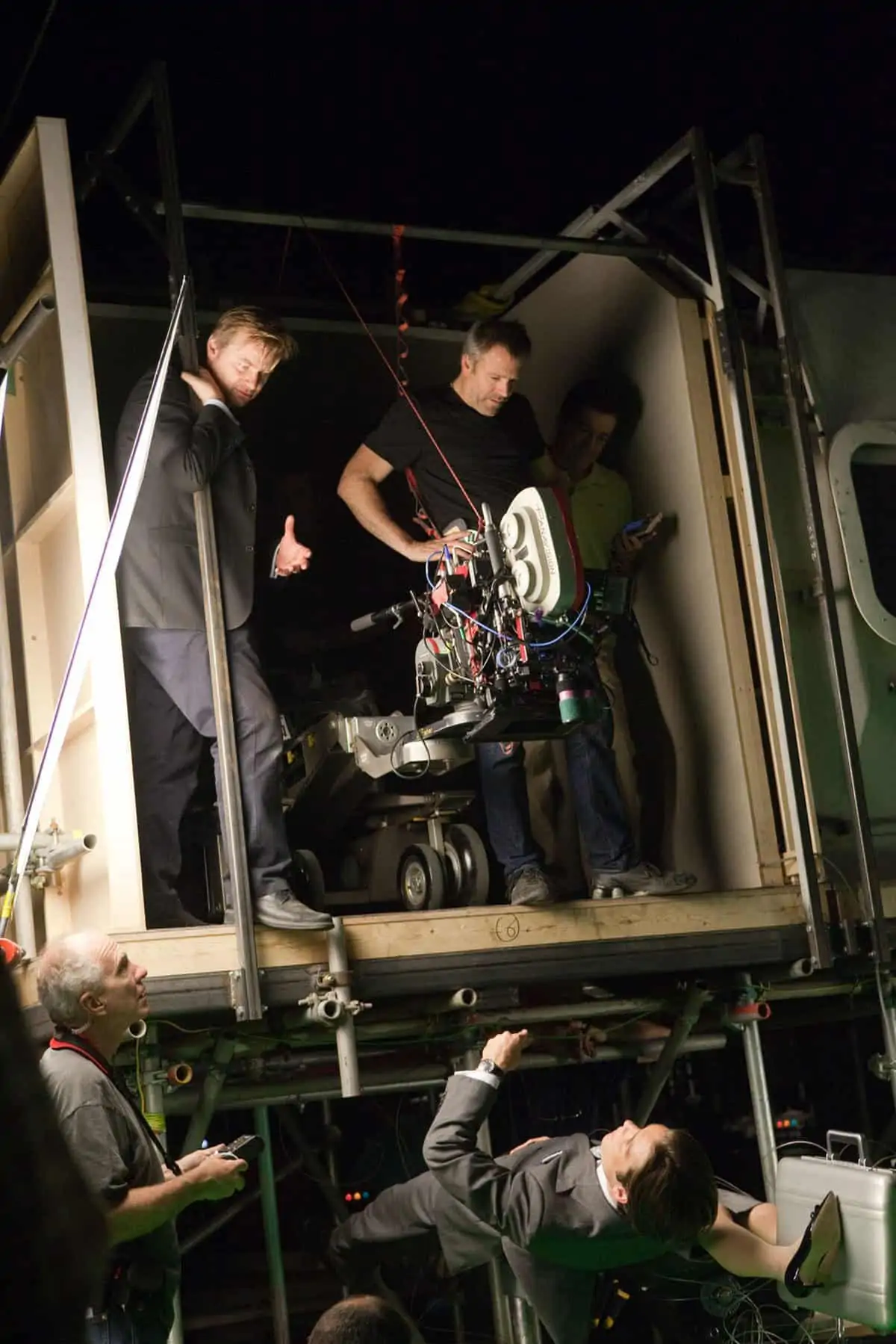

A fight scene was staged in a 160-foot long hallway set which rotated 360 degrees, while Arthur, portrayed by Gordon-Levitt, is attacked by several people. “A classic shot in 2001 inspired this scene,” Pfister says.

Arthur and his attackers seem to be walking on the walls and ceiling. It was a physical effect shot. Gordon-Levitt and the stunt men playing his attackers were suspended by wires and the camera was on a Technocrane which rotated with the set.

“We had a few small LED lights built into the floor and ceiling,” Pfister says. “We had to keep them cool, so the actor or stunt men wouldn’t be burned if they accidentally stepped on or touched one.”

Another shot was made in a second rotating hallway set where the camera was on a track that was hidden by the carpet on the floor. The camera dollied in tune with the action while the set was rotating. Pfister lauds stunt coordinator Tom Struthers, Corbould and the visual effects team led by Paul Franklin at Double Negative in London for helping to make the physical effect shots transparent.

It was a global endeavor in every way. Imagica in Tokyo, LPC in Paris, and Technicolor in London and Los Angeles handled front-end lab work, including film dailies. Nolan and Pfister share a belief that watching dailies projected on film with the cast and crew is an important part of the creative process. Pfister timed Inception with David Orr, a longtime collaborator at Technicolor. The film is being released in both traditional 35 mm film and IMAX formats. The conversion to IMAX was done at DKP 70MM Inc., an IMAX facility in Santa Monica, California.

How the legacy began...

Christopher Nolan was a Super 8mm film aficionado and enthusiastic movie fan during his youth. He studied English literature during his student years at University College in London. That’s where he met Emma Thomas, his future wife and filmmaking partner.

“Studying English literature got me thinking about the narrative freedom that authors have enjoyed for centuries,” Nolan says. “It seemed to me that filmmakers should enjoy those freedoms as well. Emma and I were members of the university film society. We showed 35mm feature films during the school year and used the money earned from ticket sales to produce 16mm films during the summers.”

Following was their first feature-length film. Nolan wrote the script, directed and shot the B&W drama. Thomas was one of the producers. Their film played at festivals, including Slamdance in Utah. Maybe it was destiny calling. Nolan saw The Hi-Line at the nearby Sundance Festival.

“It was a beautifully executed film that clearly had a limited budget,” Nolan says. “I had to meet the guy who shot it.” The guy was Wally Pfister, ASC who was also in the dawn of his career. The rest of this story is history that is still in the making.

“It’s an incredible relationship which has evolved over the years,” Thomas says. “I love watching them work together. There is sort of magic on set. There is no hesitancy or miscommunications. I’m not saying they don’t discuss options. They spend a lot of time discussing the script and what is right for the movie. Wally has a great sense of story. Working on films with the two of them is a dream for me, because apart from the fact that they create magic together, they are super-fast, and there is no drama between them, because of the mutual respect they have for each other.”