REIMAGINING THE MAGIC

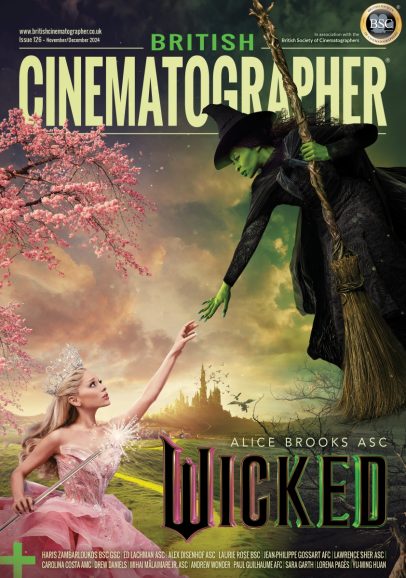

Alice Brooks ASC’s considers musicals to be the most magical genre, so when director Jon M. Chu invited her to join him in translating the Wicked world from stage to screen, it was a once-in-a-lifetime adventure she could not resist.

Two decades after the now infamous musical Wicked made its Broadway debut, filming on director Jon M. Chu’s screen adaptation began. Teaming up with his regular collaborator and friend since film school, Alice Brooks ASC (In the Heights, tick, tick… BOOM!), the pair created cinematic wizardry, bringing spellbinding scenes to fans of the stage musical and those new to the Wicked world of wonder.

In the spring of 2021, when Chu called Brooks to share the news he had found their next project, the cinematographer was thrilled to create a large lookbook of ideas to present to Wicked producer Marc Platt. “It was during the pandemic so we had our first meeting on Zoom and when I asked Marc if I could present my ideas, he said, ‘Oh no, we’ll figure out what the movie looks like when we’re making it.’ So I guessed I’d got the job!”

Chu began adding his ideas into the screenplay during a lengthy prep process, exploring the creative goals and intentions for the movie with Brooks before they headed from the US to London to begin further prep. On their second night in London, they joined choreographer Chris Scott, production designer Nathan Crowley, costume designer Paul Tazewell, hair/make up/prosthetics designer Frances Hannon, visual effects supervisor Pablo Helman, and producers Platt and Jared LeBoff on a trip to the West End to immerse themselves in Wicked the stage musical.

“As we sat there in amazing seats watching the show, it felt like we were on this journey together,” says Brooks. “Like Dorothy, the Tin Man, Scarecrow and Lion, all linked arm in arm, walking down the Yellow Brick Road together on this creative adventure where Jon gave us unlimited possibilities.”

The director encouraged the crew to avoid choosing the obvious and instead make creative choices that would result in “a cinematic experience unlike any other”. As Brooks highlights, “it’s very classic storytelling in many ways which was another of Jon’s goals – to tell a timeless tale”.

A reimagining of the much loved story The Wizard of Oz, Wicked introduces audiences to Glinda the Good Witch and her unlikely green-skinned friend Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West. To do justice to the story and musical treasured by so many and feature all of the songs, the tale is split into two movies, filmed back to back, with the second film due for release late in 2025, being darker in tone. Part one of the story of love and friendship is a reminder that there are two sides to every story as we follow Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) and Glinda (Ariana Grande) from birth to college and discover what led Elphaba to be labelled “wicked”.

Despite Wicked being set in a vast and epic world, at the heart of the stage play and films is an intimate story about two best friends’ relationship. Therefore when Chu asked Brooks what her goal for the movie was, she replied, “That it is the greatest love story ever told between these two women.”

“So the close-ups were going to be everything to us,” she says. “And we started testing lenses and making very specific choices, some based around the original Wizard of Oz books by L. Frank Baum. Every paragraph has incredibly rich colour description and colour has symbolism to indicate how a character might feel.”

With colour deeply connected to characters’ emotions, Brooks explored how to light the movie based on what Elphaba or Glinda experience. Working through the script with Chu, she suggested time of day, included her wish for the sun to always set for Elphaba and rise for Glinda. “So Glinda meets prince Fiyero in the morning whereas Elphaba meets him at night,” she explains. “In a scene in the forest with the prince there is one long eight-minute sunset where the colour temperature of the ambient light slowly changes and a huge light (two Dinos) on a lift is placed in the distance acting as the sun. And at the end of the movie we created a 40-minute long sunset.”

Framing the fantasy

Other than colour of light, lensing and framing choices aided the visual storytelling. As well as traditional framing, sequences when Glinda and Elphaba look direct into the lens at each other immerse the audience in a different way by breaking the fourth wall.

From their meeting at Shiz University through to a dance routine in the OzDust Ballroom and a performance of the song “Popular”, the moments of connection between the two women are pivotal points in the narrative. When the pair are “connecting for the first time” in the ballroom sequence Brooks chose to capture the action through 360 degree shots as the camera spins around the characters.

Despite normally matching lenses for close-ups, during early lens tests Brooks and Chu discovered Elphaba’s close-up lens was a 65mm whereas Glinda’s was a 75mm. “The 2.40 aspect ratio was also important in our decision making as the two women are in so many shots together and share the frame so beautifully in that wide aspect ratio,” adds Brooks.

As the ability for Chu to run long takes was essential, digital was always deemed the most appropriate route. Some Steadicam shots in the OzDust Ballroom were eight to 10 minutes, depending on how long the actors performed, because Chu didn’t want to cut to ensure every second of their emotional performance – which “sometimes moved the crew to tears” – was captured.

After exploring multiple camera options Brooks initially opted to shoot on the ARRI Alexa LF. But after seeing further lens tests projected at Company 3, including some on the Alexa 65, Chu and the cinematographer realised that camera offered the intimacy they desired plus the ability to capture the scale of the huge sets and scope of the world being created.

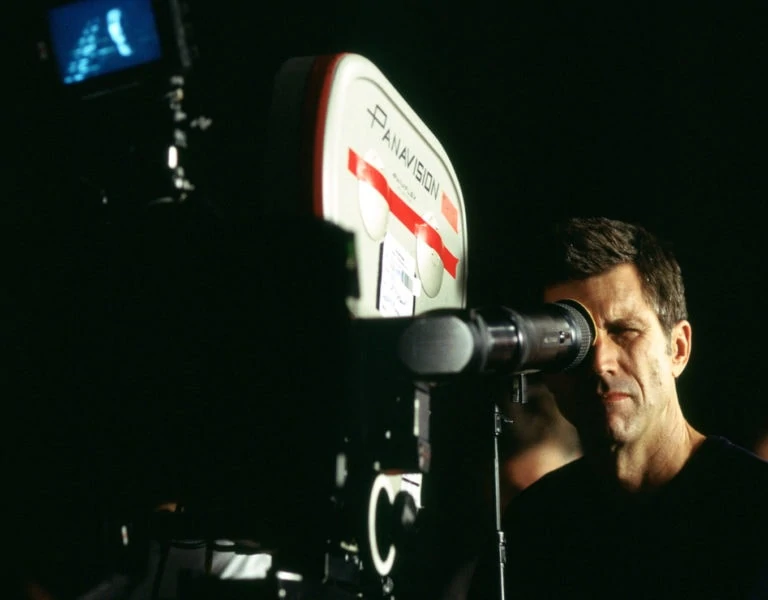

“I knew we would shoot anamorphic and had already started developing a series of lenses with Dan Sasaki at Panavision to cover the sensor size of the LF,” says Brooks. “When we decided to shoot Alexa 65 he wasn’t sure if he would have time to make a new set that covered the sensor but when the shoot pushed by six months, it allowed enough time for a new set to be created.”

Sasaki and Brooks developed what eventually became the Ultra Panatar 2s but referred to them as the “Unlimited” because of the unlimited possibilities they would create for the movie. Panavision flares are usually blue but Brooks felt the combination of blue, green and pink was incorrect, so she asked if Sasaki could develop amber flares, highlighting the feeling she wanted to achieve as a combination of “softness and weirdness” and to adopt a “non-traditional” approach that was “not the obvious choice”. To create a little additional softness on the characters 1/4 Tiffen Glimmerglass was used throughout the majority of the movie.

Studio sorcery

Creating the magical world demanded most of the action be captured in a studio environment and Wicked was the first production to shoot at Universal’s new Sky Studios Elstree, across 17 stages. But as Universal was finishing building some of the stages when shooting started, production began at four stages in Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden and two at Elstree Studio Platinum Stages.

“Sky Studios Elstree is incredibly efficient, and shooting In such new stages helped us become more sustainability due to the airtight building infrastructure and power solutions,” says Brooks.

It quickly became clear the scale of the sets was bigger than anything most of the crew had encountered, so Brooks started “living in” production designer Nathan Crowley’s art department, studying the drawings and 3D models. “Wicked was a huge learning curve for us all and none of us had worked on anything of that scale, so it was an even playing field,” she adds.

To determine whether virtual production techniques would be suitable, Brooks and Chu visited Manhattan Beach Studios in Los Angeles, but when the sets started being designed it was clear the scale would not be a perfect fit for a volume shoot. Brooks believes “you need the sets to be quite small for virtual production and that wasn’t our movie”.

Chu also likes “real and tangible things” as demonstrated in a beautiful photo Brooks took of him wearing the cloak Elphaba would don in a scene in Emerald City. “Jon’s standing in a window and spinning, before the actors came on set, and feeling what it would be like to put that cloak on, and how you would move in the space,” says Brooks. “So when we looked at the virtual production stage, it didn’t align with his approach. He wanted to be able to pick up an object or turn on a light and to be able to use an entire set that you dress and light 360 degrees.”

Due to lack of space on London backlots, the foundation for the sets was initially constructed on a turf farm in Ivinghoe, outside of London. Construction began in September and shooting commenced in April. Outside of the studio, some sequences were captured in Norfolk, Seven Sisters (for the river scene), and plates were shot of the White Cliffs of Dover (for the Wizard and I sequence). The entrances and exits to Shiz University when Elphaba and Fiyero ride a bike were shot in Windsor, as was the exterior of Dr. Dillamond’s property, and Elphaba and Glinda’s scenes in a poppy field.

When the stages were being constructed for the big forest scenes the partition between two of them was not built so the forest was even more expansive. Epic Games Unreal Engine was an invaluable tool to previsualise sets for such sequences, as some of the exterior sets were the size of four American football fields. Brooks considers the process a “complete collaboration of art, lighting, and lensing” because the art department previs starts with concept art rather than looking at lensing. She would then “show them in Unreal what it would look like with the lens and camera package and the look would evolve from there”.

Unreal opened up many possibilities during the planning and decision-making stages, allowing them to see the sun path at any time of day based on the sets’ height and where the sun would hit. And by taking early models into Unreal, such as those for Emerald City, Brooks, Chu and choreographer Scott realised a long Steadicam shot planned to rise up on a crane would not show off the environment enough and instead needed to be lower to emphasise the scale and height of Emerald City.

“We could put our lighting cranes into Unreal and see how far our reach would be. Some sets like Shiz University needed to be scaled down as they were too huge and the lighting cranes couldn’t reach. Our Technocrane had to be lifted onto the set by a construction crane,” says Brooks, who along with gaffer David Smith made suggestions to Crowley and set decorator Lee Sandales regarding what practical lighting should be built into the ginormous sets.

“For example, the Hall of Grandiosity in Emerald City featured arches, but it was just this dark tunnel with nothing in it. So we asked them to space the arches 10 inches apart, so we could incorporate LEDs and change the colour,” she adds. “In the throne room there’s a huge ceiling many people assume is visual effects but it’s real. We needed enough gaps to put SkyPanels on every level around each concentric ring. And we built an 18-inch model version of the giant 18-foot Wizard’s head to experiment with which informed us it should be lit theatrically. We used huge old theatrical light bulbs, and beautiful structures were built to put them inside the rope curtain of the Wizard’s head.”

Colour considerations

As make-up and prosthetics were at the forefront when carrying out camera tests, Brooks started working with hair/make up/prosthetics designer Frances Hannon in the second week of prep. Elphaba’s green skin was pivotal in their experimentation, with the team initially being unsure if the colour would be best created using visual effects or through three hours of makeup each day.

They started by testing makeup on a stand in with the same skin tone as Cynthia Erivo who plays Elphaba. “We found the perfect green but when we put it on Cynthia and did still camera tests and some in front of the Alexa 65 the green didn’t look the same,” says Brooks. “Frances explained it’s because people have different moisture levels in their skin even if the tone is the same, so the colour of the makeup looks different.”

Therefore Erivo needed to sit through makeup tests, during which the creative team decided visual effects would not offer the solution to create the green tone. “Cynthia felt different in makeup, acted different, completely transformed and the actors around her also acted differently, which was fascinating,” says Brooks.

Emphasis was also placed on the colour of the environments the characters would inhabit. The OzDust ballroom set is made of clear resin and could be made any colour the team desired, leading to lighting and camera tests with costume designer Tazewell, during which Brooks noticed that any time Erivo in green makeup was near cyan blue, her colour popped.

“The OzDust ballroom scene is the heart of the movie as it’s where these two women fall in love with each other and where Glinda suddenly really sees Elphaba for the first time,” says Brooks. “I wanted that cyan as it’s the colour that makes Elphaba look most beautiful, so we backlit all the walls with cyan lights that undulate, shift and grow.”

Emotional storytelling

A shared enthusiasm from the crew was palpable throughout the entirety of the shoot including from gaffer David Smith (Star Wars Episode VIII, Spectre, Guardians of the Galaxy, Mary Poppins Returns) who was keen to analyse drawings of the complex sets and work with the art department from day one as they would require equally sizeable lighting rigs. “Once I get the set drawing, I add all the lights where I think they should go before presenting it to Alice so we can discuss and move forward creating the looks,” he says.

While incorporating the theatrical influence of the Wicked stage show, the aim was also for the film to be grounded and real. In addition Brooks tried to incorporate at least one colour of the rainbow at each stage of the two films. The desired look was achieved working with a hybrid system of old and new fixtures, predominantly LED and part tungsten with lighting fixtures – supplied by Universal Production Services, with some sub rented from MBS – including Creamsource Vortexes, SkyPanels, and Universal’s own brand Cineo using Quantum IIs.

“We used a lot of LED fixtures so we could change the colour and intensity throughout the various sets, interiors, and exteriors to achieve different looks,” says Smith. “But some sets required quite strong light because they were so big, so we also used conventional tungsten lights, Par Cans, Dinos, 20Ks and Soft Suns for exteriors.”

The AquaBat fixtures – long waterproof LED tubes that create a soft light which were developed by MBS for Smith to use on Eternals – were also valuable on Wicked due to their versatility of colour and shape. “We made the decision for the sun to set in the Emerald City sequence, so we needed the end of the Wizomania scene to be in evening light. The only way to do that was to shoot night for evening because we were outside,” says Brooks. “The winds on the farmland we were shooting on were so high so the AquaBats were perfect. They sat in 20 by 20 frames off construction cranes to create an ambient light level and because they were soft they didn’t need silk underneath, meaning we could fly them and the wind would go through the gaps between each unit.”

A large number of Dinos were used as the sunlight source, creating the feeling of a setting sun bouncing off reflective surfaces in Emerald City. Elsewhere, the vast forest set required around 1,000 Par Cans lining the stage producing sunlight hitting the trees. As nature was also a significant part of that set and the large, swirling, moss-covered trees blocked some of the light, the Greens team attended pre light days to either clip back parts of the trees and shrubs or add in more which lights could be hidden behind.

Moving lights also featured throughout the forest set and elsewhere in the movie including placed on top of cranes at Shiz University for night exteriors. In the OzDust Ballroom scene the crew wanted to create a subtle underwater feeling using rippling lights which was achieved through a combination of large water trays containing vibrators and moving lights which span around to produce an inconsistent, constantly moving effect.

Brooks finds moving lights incredibly versatile when working on such big sets because if Chu wanted to block a scene differently, the crew could quickly move the light, soften it or put a diffusion on it using the iPad. “The way Jon works is driven by intuition and feeling – the emotion is everything to him – and so as his creative partner, I understand we need to be as flexible as possible which moving lights allowed,” she says.

Smith agrees working with moving lights – predominantly Ayrton Dominos – opened up additional possibilities as they could not only be moved quickly but the shape and colour could also be altered. “And because most of the sets were 360 degrees and 40 or 50 foot high, it was useful to be able to focus the moving lights quickly,” he adds.

Also on the agenda was determining how to light and balance a green-skinned character who almost always wore black, versus Good Witch Glinda with platinum blonde hair and always dressed in pink. How should they make both women look and feel the way they needed to in different emotional beats? Smith was “constantly mixing lights up and down to change the exposure as the characters moved around” – another advantage of using LEDs.

As well as lighting faces and spaces, it was important to ensure the costumes shone. The beautiful pleating in Elphaba’s dresses needed to be captured but black is difficult to shoot and can disappear, so costume designer Tazewell gave Brooks swatches of potential fabrics to camera test. Working with Smith, Brooks then determined how to light the dresses so the audience could see all the texture and work that went into each costume. The solution, as Smith outlines, was “being careful about exposure and where the light came from”.

Choreography and camera movement

Brooks pushed for A Camera/Steadicam operator Karsten Jacobsen to have 10 weeks of prep, attending dance rehearsals and learning the dance moves. “It’s unusual for a studio to agree to this amount of prep time but they did. In many ways, he became one of the dancers and having him on board so early was essential as he was so ingrained in the story and his framing choices were beautiful and specific to the emotion of each scene,” says Brooks. “These complicated Steadicam moves or crane shots also required our key grip, Guy Micheletti – who has worked on crazy huge movies – to recable one of our four cranes three times. He said he had never done so many complicated moves in a single film before.”

Capturing the choreography at the centre of many sequences involved visual experiments during dance rehearsals when Brooks, Chu and Scott shot on iPhones and Jacobsen captured footage on an iPad. “We’d shoot different angles and as the dance rehearsals evolved give Jon the footage which he’d start to cut together,” says Brooks. “One day I realised Karsten and I shot the same camera move with our iPhone. That’s when I knew this was going to be an amazing cinematic relationship.”

Brooks, Chu, and Scott have enjoyed a successful creative collaboration for 15 years since they made Hulu’s first original content/web series The Legion of Extraordinary Dancers about superheroes whose superpowers are their dance moves. “At the time we didn’t realise what we were doing was a sort of sandbox,” says Brooks. “No one was overseeing us, it was very small, we could make mistakes and try things and really learn to tell a story through dance and music.”

Over the years the scale and budget of productions the trio work on have evolved but, as Brooks highlights, “even though we’re now making one of the biggest movie musicals of all time, it’s still just three best friends making productions together. We trust each other, are always incredibly honest, and all have the exact same intention – to make the best movie and tell the best story possible”.

To immerse some of Brooks’ collaborators – key grip Micheletti, gaffer Smith and her assistant Marin Kawamori (who helped with research and development) – in creative conversation, she started a movie club on Wednesday afternoons, picking a different film each week to watch and discuss.

“At first David [Smith] told me it was crazy because we had too much work to do but we all found it valuable. We talked about what we liked and had an aesthetic discussion about taste which had nothing to do with Wicked,” says Brooks. “We got to know each other as artists and started developing the same language. It was such a special time and really bonded us.”

Shoot for the sky

Every choice was incredibly considered, including the nine million tulips – each row a specific colour – which were planted according to where the sun would be at a specific time of day in April in Norfork for one scene captured by drone and crane. Munchkinland was then comped into the scene in post, using Unreal to match the drone footage with what was captured in the backlot.

“It was crazy because we had paparazzi following us who unfortunately had their drone right above our set, over our actors,” says Brooks. “Drone rules state you can’t fly over actors so we were thinking, ‘How come this paparazzi can fly their drone but our aerial teams can’t?”

The Helicopter Girls drone team were recommended to second unit director, Sam Renton, for the execution of a thrilling woodland chase sequence. The company’s work, particularly in the field of FPV drone work, seeks to innovate with technology and its application. “The FPV work Luke (Bannister) and Will (Roth) managed to achieve was incredible,” says Renton. “The speed they flew at and the accuracy they delivered enabled us to think differently about a sequence that, without their ability, may have ended up boring and pedestrian.”

A continuous conversation with visual effects supervisor at ILM (Industrial Light & Magic) Pablo Helman and his team was necessary for such sequences, with Helman frequently attending DI sessions and Brooks invited to VFX reviews to share feedback and lighting notes. As the pair and production designer Crowly agreed they wanted to achieve as much as possible in camera, many sets were tall so they did not require much set extension. Brooks also likes to work with one LUT and believes that, especially on a visual effects movie, having one LUT makes everything seamless.

“We were very close to the shooting LUT and our CDLs when it came to the grade with Company 3 colourist Jill Bogdanowicz who is such a fantastic collaborator. So we were mainly making the film richer and deeper while still retaining a soft, warm, and effervescent feeling,” says Brooks, who was also thankful to have been involved in timing the trailers as well as the final movie to ensure visual consistency. “It also gave us time to try things and see what works and what doesn’t early on.”

She also treasured her collaboration with editor Myron Kerstein on Wicked, marking their fourth creative union. Brooks would call him each day after she wrapped shooting around seven hours of dailies and Kerstein would watch every frame in a screening room they built at Sky Studios Elstree and give feedback. “It was a very hard and exhausting movie – the sets were massive, when we were outside it was muddy and the weather was awful – so when Jon invited any of the team into the screening room it kept reviving people’s spirits,” says Brooks. “Having a real creative partner like Myron in those sessions was invaluable.”

The magic of musicals

Brooks believes the musical is the one of the greatest cinematic genres because “it’s an extension of what a character feels”. Making a musical such as Wicked about friendship and family with a tight knit crew and cast had an even greater significance for the cinematographer. “It was just the most wonderful group of people sharing this very special time when we all got to be in Oz for 12 months and create something I think is really magical.”

When the cinematographer landed at the airport recently she spotted a quote from former US president John F. Kennedy she felt was very apt and related to the experience of making this incredibly special musical. It said, ‘We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills.’

“I feel like in going to Oz and creating the world of Wicked, we really did go to the moon and fulfilled our dreams,” says Brooks. “You only get to do that once.”

Comment / Amelia Price, chair, sustainability committee, PGGB