Never Surrender

Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC / Darkest Hour

Never Surrender

Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC / Darkest Hour

BY: Ron Prince

French cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC says he was encouraged by the creative vision of innovative director Joe Wright to shoot what initially seemed an unlikely choice of project: the story of the newly-appointed British Prime Minister during the early days of World War II, and his decision about whether to negotiate peace terms with Hitler or to fight against the Nazi regime.

But the determination to employ Delbonnel, whose credits include Amélie (2001), Harry Potter And The Half-Blood Prince (2009), Tim Burton’s Dark Shadows (2012), Big Eyes (2014) and Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children (2016) and the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), proved more than a solid choice. Made for just $15m, and returning $140m at the box office so far, Darkest Hour stands as one of the year’s best films, with Gary Oldman’s Golden Globe, BAFTA and Oscar-winning performance as the formidable UK premier, Winston Churchill, suitably underpinned by Delbonnel’s striking and beautiful cinematography. Indeed, Delbonnel himself was the recipient of several nods during the 2018 awards season for his work on the movie, including BAFTA, ASC and Oscar nominations.

Although Darkest Hour was Delbonnel’s first collaboration with Wright, it wasn’t through the director’s lack of wanting to work with the cinematographer. “Joe called me three or four years ago when he was prepping for Pan (2015), as Seamus (McGarvey BSC ASC) was not available, and asked me if I could shoot it for him,” says Delbonnel, “But I was working with Tim Burton on Miss Peregrine at the time, so I could not shoot it. Joe also called me for this one, as Seamus was not available again, but I was. I am not perhaps the greatest fan of historical biopics, but I am a great admirer of Joe’s work. I read the script, knowing that Gary was already signed-up to play Churchill, and said I was interested.

“Joe came to see me in Paris and, over the course of a few days we discussed the treatment of the movie. He outlined that it was more about Churchill’s complex and troubled personality, his frequent loneliness, isolation and self-doubt as a world leader, than it was about a moment in world history per se – which really engaged my attention,” admits the cinematographer. “Joe also talked about those old-fashioned battlefront war maps, and the aerial view they gave of soldiers, armies, human life being played with by politicians and generals, as if from God’s point-of-view. It was from these starting points that we developed our concepts of what the movie could look like.”

Regarding creative references, Delbonnel says, “I don’t really look at filmic references these days. I prefer to read the script and imbibe the research done by the production – in this case photos of the era found by the production designer Sarah Greenwood. For me it’s as if the images are the melody in a musical score, moving with contrast, between light and dark at different paces. Cinematography is about how you articulate the melody of the light.”

Accordingly, Delbonnel, who was aware that the spring/summer of 1940 was one of the sunniest on record, decided to give Wright the option to play with light and dark in order to convey Churchill’s conflicted character. In the opening scene for example, Churchill’s visage emerges from the pitch-black of his bedroom by the sudden illumination of a cigar match, before the butler opens the curtains to broad daylight. “The audience see the character literally coming to light from the shadows,” says Delbonnel.

The same visual theme repeats during Churchill’s first, tense meeting with King George VI at Buckingham Palace, in which Churchill is, by turns, bathed in hard sunlight before being swallowed by the shadows, as he strides along the palatial corridor towards the monarch. For Churchill’s June 4th address to The House Of Commons, after the desperate, but successful, evacuation of Dunkirk, the movie’s climactic visual scheme dramatically contrasts its opening moment. At first, Churchill is hiding, with just his bowler hat on the front bench in dark shadow, but by the end of his famous oration, the Prime Minister is there, right in the high-contrast spotlight.

Photography on Darkest Hour began in November 2016, after a two-month prep. Sets of The House Of Commons and The London Underground, were built at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden, with the warren-like Cabinet War Rooms constructed at Ealing Studios. Production also encompassed London landmarks such as Her Majesty’s Treasury and 10 Downing Street – blackened in post production to give a suitable sooty wartime look. Other locations included Manchester Town Hall for Westminster, a house in York that doubled for the interior of No. 10, and Wentworth Woodhouse, near Rotherham, in South Yorkshire, which simulated the long corridor of Buckingham Palace. Production wrapped in at the end of January 2017.

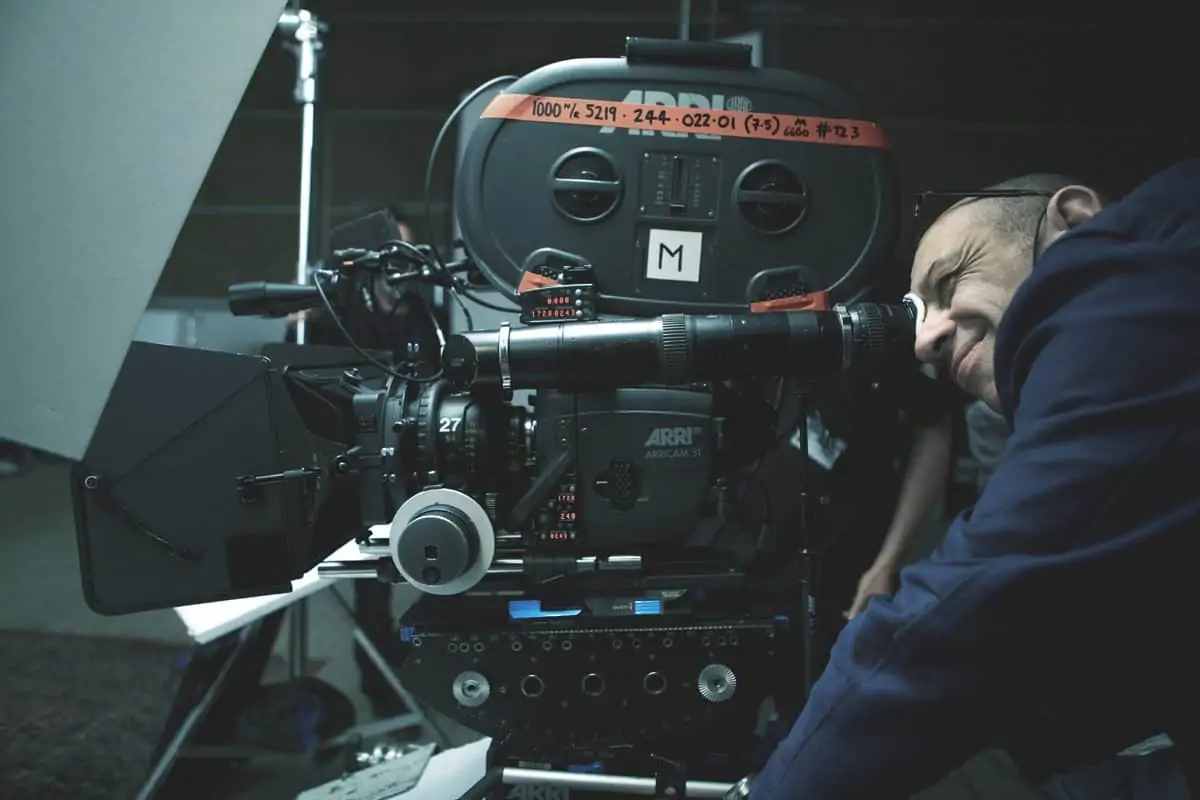

Whilst Wright would have loved to have captured Darkest Hour using ARRI Alexa 65, Delbonnel realised that the lack of speed in the lenses militated against its use in the many darkly-lit interiors, as did its physical-size in terms of handheld manoeuvrability in such confines as The Cabinet War Rooms. This led him to shoot using the ARRI Alexa, paired with Cooke S4 lenses, plus a lightweight Fujinon zoom, with the camera set at to his preferred 500ASA rating. “For the way I work, the 500ASA gives richer blacks and the noise is less obvious,” he says.

The production shot in 1.85:1, with Delbonnel’s favourite LUT – developed by the cinematographer and colourist Peter Doyle to yield a slightly desaturated image with slightly higher contrast – applied to the footage non-destructively on-set. Peter Marsden was the DIT on the production, who Delbonnel describes as “well-organised and a great collaborator.”

Delbonnel and his director were highly aware of the need to keep the camera moving as much as possible, in a bid to visually offset a number of long dialogue scenes which accounted for about of fifth of the movie. This saw the deployment of the Stabileye camera stabilisation system.

“In some ways, Stabileye is more interesting that the traditional Steadicam for bringing a kinetic energy to the images,” says Delbonnel. “Of all the gyro-stabilised systems out there, Stabileye is by far the best.”

"For me it’s as if the images are the melody in a musical score, moving with contrast, between light and dark at different paces. Cinematography is about how you articulate the melody of the light."

- Bruno Delbonnel AFC ASC

Delbonnel especially liked its deployment during the scene in which the camera follows Churchill’s meandering walk through the labyrinthine Cabin War Rooms. This saw the Stabileye/camera moved between marks by one of the grips and A-camera operator Des Whelan framing the action via the remote head controls. “The corridors were just too narrow for a traditional Steadicam, but the Stabileye is slimmer than the shoulders of the person carrying it. Thanks to Des’ framing, the results looked amazing.”

The production also harnessed the cable-running capabilities of the Stabileye system to support Wright’s desire for aerial views, such as shots of French refugees fleeing the warfront along rustic roads. For the dramatic scene at Calais Castle, when Brigadier Nicholson learns of the sacrifice of his men, the Stabileye camera was initially tracked backwards on-foot, before both the grip and the kit were hoisted high in the air above the set-floor.

The production was planned chiefly as a one-camera shoot, with Whelan ably assisted by first AC Julian Bucknall, and key grip Paul Hymns. However, Delbonnel deployed extra cameras, on occasion, principally to assist the actors. Additional cameras were operated by Simon Finney and Carlos de Carvalho.

As Delbonnel explains, “Joe prefers to shoot with one camera, but some of the longer dialogue scenes, such as in The Cabinet War Rooms, and especially Churchill’s concluding speech, involved several pages of dialogue. It was exhausting for the actors, and particularly so for Gary, who had to endure several hours in prosthetic make-up every day before he arrived on-set. So we had extra cameras on these occasions to avoid the actors having to perform a scene too many times.”

When asked about personal favourite scenes in the movie, Delbonnel cites two polar opposites – namely the Buckingham Palace meeting between Churchill and the King, at which point the two men disliked one another intensely, and the touching moment when the King visits Churchill’s decrepit bedroom to reassure the near-catatonic PM of his trust in making the right decision as regards the country’s future.

“The castle corridor, in which we shot in the Buckingham Palace scene, has 17 windows, ” Delbonnel says. “Although it was expensive, I suggested to Joe that we fire ARRI Max’s through specially-constructed boards on every window, to create strong shafts of light, so that Churchill could move to between light and shade towards the King. When Joe saw the effect he liked the idea of playing with it.”

The other scene of the fragile Churchill, alone in his attic room, could not have been more different. “I lit it the room with just one clear 200W bulb, which gave an acid yellow colour that I felt really supported the idea of Churchill’s mental torture over doing the right thing.”

The cinematographer salutes the work of his gaffer Chuck Finch, as well as the lighting/electrical crews in support of his work throughout the shoot.

Delbonnel conducted the DI grade of Darkest Hour with his regular colourist, Peter Doyle, at Technicolor, London. The pair have graded ten movies together.

“I can't work without Peter,” admits Delbonnel. “The DI is a big place for me, and I like to use all of the tools there to continue to explore and evolve the look of a movie. It’s a magnificent, creative tool and we should use it as much as we can. You can’t change the light, but you can push the contrast, desaturate and diffuse the images – all of which I did with Peter. We explored all manner of looks – such as Kodak Ektachrome and Kodachrome, as well as some of 1940’s colour photography by Cecil Beaton – but pulled back from these and found our own look from the black, browns and blues of the production design.”

As for the success of Darkest Hour at the box office and on the awards circuit Delbonnel says, “For the cinematographer, your next movie is always a gamble and the reaction to it cannot be predicted. As happened with Amelie, I never imagined the Darkest Hour, would become so big and be so well-received. It is a pleasant surprise. I owe a lot to Joe, my crew and Peter Doyle, in making Darkest Hour look the way it turned out.”