THE POWER OF LOVE

When lensing an amalgamation of haunting and precious memories and heartbreak, director Andrew Haigh and cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay SASC wanted to avoid being too heavy handed with nostalgia, instead opting for a subtle and organic visual expression of reminiscence and relationships.

Much like the journey of reflection and discovery that unfolds in author Taichi Yamada’s novel Strangers – a traditional Japanese ghost story of love, loss, the afterlife, and treasured and sometimes painful memories – the process of translating the book for the screen took writer-director Andrew Haigh (Lean on Pete, 45 Years, Weekend) on his own emotional voyage.

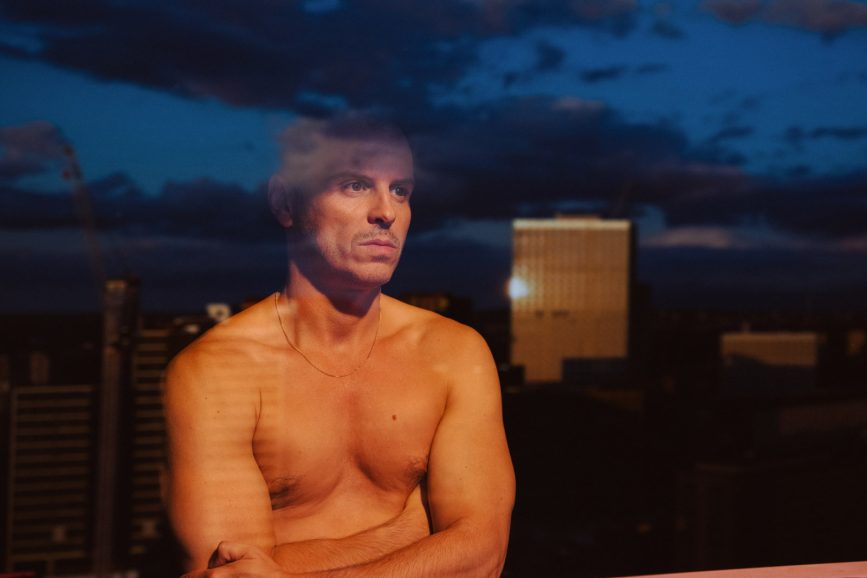

In Haigh’s cinematic reimagining, All of Us Strangers, we meet Adam (Andrew Scott), a 40-something gay screenwriter who lives alone in a high-rise flat in London. Still impacted by grief from the traumatic incident in his childhood which claimed the lives of his parents, when Adam meets Harry (Paul Mescal), who lives in the same block of flats, the love that grows has a transformational power.

Returning to his childhood home, Adam is transported back to the ‘80s and as past and present collide in a nostalgia-infused dreamlike world, he has the opportunity to spend moments with his parents who have been frozen in time at the age they were when they passed away. Memories of those he has lost and feelings of grief and suffering are revisited as Adam has conversations he wished he could have experienced if his parents had lived to see him reach adulthood.

In the telling of an ethereal tale of the power of love, Haigh wanted to “pick away” at his own past in the same way as protagonist Adam, even choosing to shoot the scenes with Adam’s parents at the director’s childhood home in Croydon, South London. “I was interested in exploring the complexities of both familial and romantic love, but also the distinct experience of a specific generation of gay people growing up in the ‘80s,” says Haigh, wanting “to move away from the traditional ghost story of the novel and find something more psychological, almost metaphysical.”

Speaking on a panel session following a BAFTA screening of the film which British Cinematographer attended, Haigh spoke of his interest in “the need to connect, or to soften whatever the pain is that you carry around with you.” While some changes were made to the story that unfolds in Yamada’s book, the central idea of the protagonist getting the chance to meet his parents, and “go back in time to have those conversations again, get to know them and them get to know him” felt really powerful to Haigh.

“I wanted to incorporate the idea of a love story into that and see how those two things connect and bounce off each other,” says the director. “There is a sense of yearning – he has lost his parents and is yearning for them as well as yearning to find someone to give him comfort and love. His parents are also yearning to be alive again and to spend more time with their child.”

A fresh narrative

The script stood out as extraordinary to Jamie D. Ramsay SASC, a cinematographer who finds it “rare to come across a piece of literature in script form that excites you, feels fresh and unlike something you’ve seen before.” He was fascinated by exploring the way people deal posthumously with trauma. “It touched me because there’s a lot of emotion attached to the subject, especially for those who grew up feeling prejudice against homosexuality and uncomfortable to come out to their parents. That was a childhood trauma that stuck with Adam, coupled with the grief he experienced,” says Ramsay, speaking to us from the location of his next production.

The feeling and “the way the movie moves you” always come first for the cinematographer, and is then “serviced by the next layer which is the choice of lights, glass, and style. “So in this film, there’s the feeling of loss as well as the emptiness of never being able to get the acceptance of the two most important people in your life. The relevance of the story to the current day when isolation is all too common struck a chord with me, and I also wanted to be part of making the movie because I love Andrew’s previous work – he’s an incredible filmmaker.

“He’s a rare director who has impeccable taste and direct sharp vision about what he wants to do. However once you have aligned with him and understand what he’s looking for creatively, he hands it over to you and trusts you completely.”

The South African/British cinematographer is familiar with lensing heart wrenching stories with sensitivity and creative flair, having won the Bronze Frog at Camerimage 2022 another adaptation of a book – Oliver Hermanus’ Living which sees a civil servant reflect on his life and how to spend his remaining days when faced with a fatal diagnosis. Ramsay’s work on All of Us Strangers also struck a chord with audiences and immersed them in another emotional story, resulting in the film being selected in this year’s Main Competition at Camerimage and scooping multiple British Independent Film Awards including Best Cinematography, Best Film, and Best Director.

Discovering the look

It is the smooth-flowing conversation between director and DP during the five-week prep and five-week shoot which Ramsay believes was key in the creative process and a result of Haigh being “super smart and knowing what he wants.” For Ramsay, a DP is “a visual ideas engine which the director then guides into place” and as Haigh knew so specifically what he wanted in terms of the story being told, the pre-production period of fleshing out their approach to the film was a joy.

“Andrew didn’t have a fixed idea of what it should look like though, which is great for me because I love the process of finding out what it should look like with the director,” adds Ramsay. “When the director is autonomous and has a strong visual idea, it’s difficult for you to collaborate and truly imprint your personality onto the film. We discovered it together through deep conversation, starting with what the narrative was really about, who the characters were, and then just talking about the references that appealed to us over the years.”

These inspirations included Ingmar Bergman productions such as Swedish period drama Cries and Whispers (1972) due to its unsettling movement, even though the narrative themes differed to All of Us Strangers. Taking creative influence from that production subconsciously and “allowing it to sit in the background” of their decision making, the filmmakekodrs explored Haigh’s wish to “create a sense of nostalgia but not be too heavy handed with it,” producing a subtle memory of sadness.

While Yamada’s book was a strong influence on Haigh, when shooting an adaptation of a novel, Ramsay “tries to avoid being affected by outside sources besides the script” and rarely reads the book because it “overprescribes your creativity and imagination”.

Discussions led them to explore the organic feeling of memories, and decide that those recollections of the filmmakers’ and protagonist Adam’s past would feel analogue. “We knew it would probably be things like 35mm prints from the ‘80s and early ‘90s, 300g printed records, a photo diary, or a tape deck which are all indicative of the era we grew up in, and the era in which the lead character went through this trauma,” says Ramsay.

The duo agreed this organic and analogue feeling would drive the visual approach – they wanted “to feel the dust on the negative, to feel that human touch to the film. We never wanted something that felt overly structured and overly perfect, it had to feel flawed.” With the touch of the filmmakers behind the lens combined with the creations of the art department shaping the final result on screen, the choice to shoot on 35mm 3-perf film was made quickly, working with Arricam LT and Kodak VISION3 500T, 250D and 50D film stocks and processing, scanning and dailies colour carried out at Cinelab.

“You can’t argue the value of shooting on 35mm film and I had great support from the teams at Kodak and Cinelab in terms of the tests and the dailies. Choice of film stock was largely driven by function as much as aesthetic. When you don’t have a huge budget for lighting and you’re using a lot of practical light, having the speed of 500T is really useful,” says Ramsay. “From a light perspective, we also did a lot of transitionary filming and having the extra bit of love out of the 250D allowed us to transition between day into night smoothly. For a lot of our daily life sequences we went for 50D because we love the robust strength it offers.”

The more vintage aesthetic was paired with cutting-edge technology in line with the filmmakers’ aim to “not be overly dramatic with the feeling of nostalgia.” Already venturing into a more organic technique of shooting on film, they wanted to avoid “adding another layer by using vintage lenses to achieve flares”. Instead they sought “the reality and responsibility of a sharp set of lenses, offset with the romance and organic nature of film” which led them to test multiple options before landing on Zeiss Master Primes.

“That contrast played with the analogue versus digital, the pastels versus the primaries which we kept leaning into,” says Ramsay. Colour palette was largely inspired by the era, selecting signifying tones that felt aesthetically pleasing as well as true to the time period. “We then worked out the evolution of those tones in a contemporary context. And whenever we went back in time, we imprinted those tones onto those moments,” says Ramsay.

A “journey of colour” that was birthed in Adam’s childhood found its way into his apartment in adulthood. “From the art department through to the camera and lighting crew, we all wanted to convey the feeling that Adam never quite grew up. He got Peter Pan syndrome and was locked into an area of his life he couldn’t move past.”

Haigh and production designer Sarah Finlay spoke about the design of the film needing to look quite naturalistic and avoid jumping in and out of the different time periods visually. Haigh’s childhood home needed to be modified in some ways to look as he had remembered it. He “wanted the past and present to bleed into each other and a lot of the design was more about feeling the past.”

Vintage meets cutting-edge

Both Haigh and Ramsay are fans of the look and feel of film, but they also wanted to create a “feeling of being out of touch with reality – a symptom of the self-induced isolation and loneliness Adam experienced.” This resulted in a collision between the analogue and digital filmmaking world, and Adam’s apartment being built in a studio at Wembley Park Studios in London. Incorporating virtual production techniques, the set was surrounded by an LED wall comprising ROE Visual Ruby 2.3mm (running on the Helios processing platform), upon which all of the views from Adam’s apartment were displayed. The 120ft by 50ft volume was built with the help of the team at Creative Technology – which supplied the LED screens – and plates were captured in and around Stratford, East London.

“In doing so, we could manage the time of day, luminance, position of the view, cloud structure, movement of traffic, or whether we wanted to do a time lapse with the clouds,” says Ramsay. “It just allowed us to put the reality a little bit outside of the realm of normal, just beyond his apartment. This helps create a slightly strange feeling in his apartment, which is a significant location as it’s where 30 minutes of the movie takes place.”

Ramsay enjoyed a harmonious combination of old and new technology, using ARRI SkyPanel LED lights to create an ambience matching the colour of clouds displayed on the LED wall in addition to 12K or 24K ARRI T12 or T24 tungsten fresnel lights to create the feeling of a sunset illuminating the room.

“I haven’t been able to achieve that with any other light besides the fresnel tungsten head which have a warmth and analogue feel,” he says. “My sweet spot is a specific combination between old and new such as using 35mm film against the LED wall to soften the wall. And by embracing LED technology to marry the colour tone of the wall with the ambience, you then create an interesting synergy with the analogue feel of an old fresnel.”

Helping Ramsay achieve this synergy was Warren Ewen, a gaffer the DP has collaborated with a number of times in the UK, who “goes above and beyond” and is “one of the strongest hands on set.” Working with a stellar lighting crew, the DP learnt about safeguarding himself from an exposure perspective and making sure there is enough lighting in place to service what is needed when shooting on film.

In addition to the benefits Ramsay and the crew enjoyed when working with the virtual set, the cast expressed their appreciation for having a visual context of the outside world displayed on the LED wall in contrast to their experiences of green screen shoots. However, Ramsay’s greatest challenge when shooting on the volume was occasionally discovering moiré in the dailies. “It gave me sleepless nights because when we got our dailies moiré might be introduced in the strangest situations – in reflections on the set as if a glass, mirror or wall was acting as a sensor,” he explains.

“That’s still a mystery that needs to be solved. It’s the hard thing about seeing your dailies 16 hours later when shooting on film. But Andrew was so collaborative and supportive throughout, knowing we were going down the 35mm and virtual production route and the emotional turmoil we might encounter along the way. But the results were well worth it.”

Prior to shooting commenced Ramsay explored technical challenges that might arise for scenes which were to be shot against the LED wall with his longtime colour collaborator, Joseph Bicknell, colourist at Company 3. “After understanding the story in broad strokes and Jamie’s perspective on it, I like to create a strong show LUT for him to load in camera during tests, so he can see live how it might react before photography,” says Bicknell. “Once we have that test footage we’ll dial in the look further, I’ll make a few adjustments and he shares his thoughts which we built into the final show LUT. The overarching look of the film didn’t end up straying far from this in the final grade.”

Bicknell felt the production was a “masterpiece” from the first time he watched the cut without final mix or colour as “all the mood and intensity was there”. Haigh and the cinematographer’s shorthand was so strong that Ramsay had a clear idea of the visual vibe the director desired when it came to collaborating with Bicknell again in the final grade. “Andrew is very supportive in that way and has a lot of confidence in the HODs he’s picked because he loves what they do. He trusts them and that’s why it’s wonderful to work with him,” says Ramsay.

Exploring the film’s emotional qualities, in the grade Bicknell and Ramsay worked with DaVinci Resolve to achieve a “light blend of magical realism to help the audience travel through the story”. On specific scenes they used colour to more forcefully convey emotion, for example during moments of distress such as the sequences that take place on the underground. “Inspiration for this was partly taken from the performances but also what was happening in the sound design,” says Bicknell.

Reacting to the moment

The majority of the narrative plays out in Adam’s childhood home, which Haigh was keen to shoot in the house he grew up in. But, as Ramsay highlights, shooting in quite restrictive spaces such as those in the house location with low ceilings and small windows would have been tricky even when working with small digital cameras. “The fact we are shooting on 35mm cameras with 1,000 foot loads made filming and lighting tough,” he says. “We managed to get permission from the property’s current owner to cut out a doorway to extend the lounge but it was still very challenging.”

Wanting to work within a wider frame to allow themselves the option to isolate characters, but also centralise characters in important moments led the cinematographer and director to adopt a 2.39: 1 aspect ratio. “There are scenes where we isolate the characters on either side of the 2:39 aspect ratio and others where we centralise the character and tighten the eyeline to a great extent,” says Ramsay, using the sequence where Adam and his parents are all in bed together as an example. Haigh and Ramsay wanted this to be an uncut scene, and to hide when the cast members in the bed needed to switch and move, creating a beautiful yet strange and jarring experience.

“This was difficult as we were on location at the house in Croydon and needed to build a cage inside the bedroom from which we could suspend the 35mm camera with a 1,000 foot mag above the characters,” says Ramsay, who likes to operate and “react to the feeling of a moment”, and was behind the camera for All of Us Strangers. “I had my grip Kevin Fraser seven inches above this rigging, operating the dual slider as the scene developed. It’s tough to find 35mm familiar crew but Kevin’s very comfortable with rigging film gear.”

Meanwhile, Ramsay was on the zoom, timing it precisely to push in so another character disappeared from the frame. “Each time they had to leave the bed without us feeling the bed move, and then another character got in and they were revealed. Building a structure to support the 35mm gear on location was difficult but what was most important to us was having absolutely no cuts in that sequence, so there was no chance to lose the audience’s attention, locking them in this dream.”

As well as not being too heavy handed with the sense of nostalgia, Haigh wanted to avoid being overbearing with the suggestion of Adam’s different states of mind, wanting the subtlety to almost make the audience question where they were and whether it was the past or present. “The only time we pushed it was the club sequence where Adam is intoxicated and that feeling was motivated more by the drugs he had taken than by the state of mind and the presence of ghosts in his life,” says Ramsay. “For the club scene, we had more free rein to really push the lighting, transitions, use reflections and break the fourth wall by Adam looking into the camera, confusing the situation.”

While pushing the camera movement and making it more confusing in that sequence, the filmmakers wanted everything else to be fairly stable, with a “slight movement and breath to it” achieved by shooting on zoom lenses and moving “constantly in and out of the zoom, to make everything feel like it was breathing a little and slightly strange.”

Difficult locations to control where the crew were at the mercy of what already existed included the Whitgift Centre shopping centre in Croydon. Shooting there demanded the crew carefully pick the time of day they were filming due to the large glass ceiling through which the sun would shine.

“Sequences that were fun to work out included the tube scenes which were shot on a tube line we had access to for a certain amount of time and could go back and forth on,” says Ramsay. “Adam’s journey always needed to appear to be in one direction, so I needed to work out when to mirror his placement on the tube and when to switch extras, so he always seemed like he was going in the right direction.”

In scenes taking place on the train, reflection was an important motif because “reflection is your self-identity” and the filmmakers “wanted to represent the decay of Adam’s psychology through the way he was seeing himself in those moments.” In line with Haigh’s subtle storytelling, the director wanted the use of reflections to be gentle and quiet rather than overbaked. “So, it was a case of choosing when to do it and leaning into what exists in reality,” says Ramsay. “For example, tube windows morph your face naturally, so we thought let’s lean into what happens in this environment and use it as a tool.”

Haigh emphasises the importance – “especially when lensing a story with queer identity at the heart of it – that the reflection a person gives to the world can be very different to how they feel. It can be quite problematic and traumatic.” The director felt it was important that Adam sees himself in a different light each time he looks at his reflection “and things are changing and he’s learning or coming to terms with things.” Another central and constant theme running through the film for crew and cast was conveying the power of love and that “long after you’re gone, that feeling of love remains.”