Introducing Pillow Fights, the London Film School Graduation Film directed by Abigail Quinlan and lensed by Blerta Kambo.

Four flatmates decide to go on a night out, but for some inexplicable reason they can never leave the flat. Pillow Fights is a short experimental film about how women are seen and if they can take agency over their image.

British Cinematographer (BC): Please tell us a little bit about your filmmaking journey so far, as well as your influences and inspirations.

Blerta Kambo (BK): For years I dreamed of studying cinematography. Even though the more time passes, the more I feel filmmaking is an editor’s medium, cinematography is the genesis, where everything ‘comes to life’, and it’s where I want to be.

My background is in photography, and conceptual art. I am self-taught and I was one of the first female photographers and cinematographers in Albania, hoping that more would follow. The general perception of cinematographers is that they are the technical people – “the camera and light people” – while I consider them to be first and foremost conceptual artists, able to show feelings through their craft. I aspire to that.

The film Ida was one of the reasons I started thinking that I could perhaps transition to the moving image, as every frame looked like a still in the style I was shooting photography. Whereas now, I take inspiration from everything: poems, music, light falling on a random building and, of course, films.

BC: Take us back to your initial discussions with the director regarding the visual approach for your film. What look and mood did you seek to achieve?

BK: Pillow Fights is a film about four women, flatmates, and friends, who decide to go on a night out, but for inexplicable reasons, they can never leave the flat. They are observed by a fifth character: the camera. When Abi (the director) first got me on board, we just had an outline (by Georgia Williams) and a powerful two-minute score (by her brother Gabriel Williams) based on Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Together with Sophie Baker, the producer, we were a strong quartet from the start.

For us, this experimental short was about the way women are seen on screen, on social media and everyday life, and if they can have agency over their image. (Also, we were an all-female crew/cast on set.)

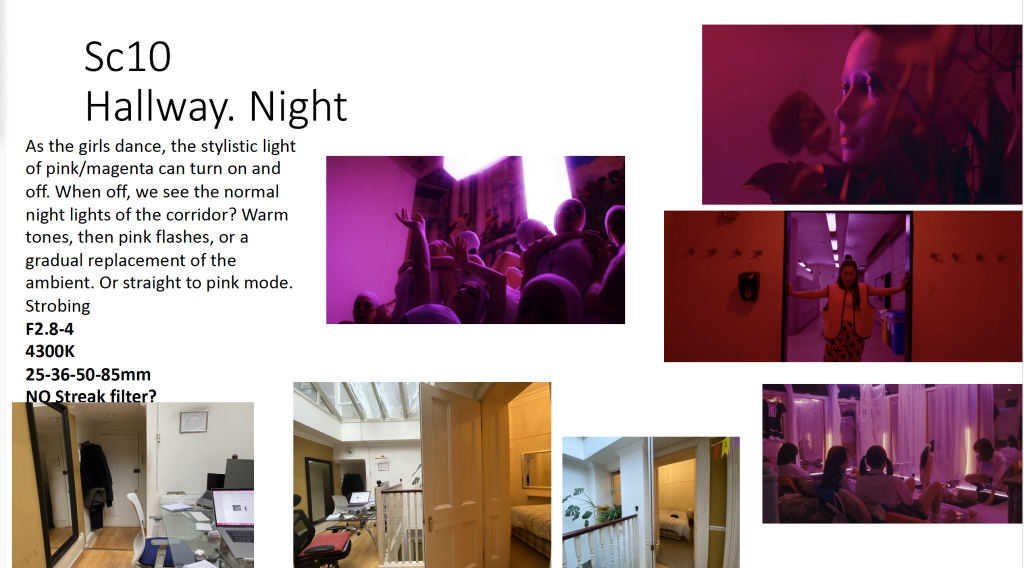

We exchanged many visual references and spoke a lot about feminist theory, the male gaze, womanhood, and voyeurism. The mood we agreed on was a kind of surreal limbo, sometimes naturalistic and at other times dreamlike (or nightmarish), stylised cinematography.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations for your film? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

BK: I had two important film references: The Exterminating Angel by Luis Buñuel and Daisies by Vera Chytilová. The latter was closer to our film, in terms of themes: a surrealist comedy bringing the anti-heroines to life. Just like Chytilová’s nameless characters, our four heroines were purposefully identified as Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 and Woman 4.

I consumed dozens of texts on feminist literature; looked at feminist artists for the past 40 years and, of course, at how women are portrayed in films and popular culture (and how many of them fail the Bechdel Test!).

Because the camera itself was a character in Pillow Fights, I decided to also operate. I had to first ask all the possible questions: does it feel like a human presence, is it floating, is it a surveillance camera, is it invasive? I found inspiration in the surrealist master, Buñuel, and ‘the repetitive scene’ – more on this later.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed?

BK: We shot inside an old Victorian house, in Marylebone. It was both a blessing and limiting in terms of movement (and lighting). The production designer, Emily Marquet, who is DP in her own right, was incredible in adapting each space to our story (and to my approach) on a budget.

BC: What camera and lenses did you choose and why? What made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

BK: I opted for a RED Komodo (6K MQ, 17:9 full frame) on an Easyrig, despite the warm tint of its red colour science. It allowed me to be handheld and react to the movement of the women, while the stabiliser gave that sense of the unnatural, the floating.

It was also ideal for the moment when the women break the fourth wall. I suggested we shoot act one in one take, in a more realistic way and as things progress, in act two, three and four, the camera becomes more invasive, more erratic, more present and we cut more often.

Initially my wish-list included both spherical lenses (for that initial sharper, cleaner, more realistic start) and anamorphic (for the distortion effect, the dreamy and surreal tone). We could not afford two types of lenses, so I picked the spherical Celere HS lenses and, in order for me to mimic the distortion quality of the anamorphic lenses (the way visible sources of lights appear) I added a Optefex clear streak filter on the lenses. This was useful to show something was off, the surreal state of things, even before the story unfolds, by having this light bending in the shots.

BC: What was your general approach to lighting?

BK: As with the camera movements, the opening sequence was to be more naturalistic (except for the streak filter).

For the ‘pillow fights’ sequence I used a flat, clinical lighting, a replica of the stock photos one finds when typing in Google ‘pillow fights’. I decided to keep the Asteras in the shot, to not hide that all of this is fake.

In another scene, I try to hint at the typical male superhero lighting: yellow and teal.

For the ending scene, when all chaos breaks loose, I opt for music video-esque stylised lighting, dark purple and red, which kind of cancel each other out.

In the ‘pillow fights’ flat light scene, I wanted a vertical aspect ratio, to reference social media. We shot it both ways: 1:85:1, like the rest of the scenes and 9:16, but only two shots of the latter made it in the edit.

BC: What was the trickiest scene to light?

BK: The bathroom scene with the teal and yellow lighting. It was a small space, and overall, we should have done tests, in the exact house. Conceptually I liked it, the way we managed the execution, not so much.

BC: Were there any other challenges of the shoot from a cinematography perspective and how did you overcome these obstacles?

BK: Scene one (a one take master-shot, filmed from two different angles, a repeated scene) was supposed to be in morning light. It was a very dark sky that day, heavy rain, and the 2.5K HMI we placed outside the window wasn’t enough, so the scene ended up looking more like afternoon. It didn’t bother me so much, since our story could accept a character waking up later in the day. In any other situation it would have probably been problematic.

BC: Who did the grade and what look were you trying to achieve in it?

BK: We had experimented a lot so I was trying to avoid over-saturation, as the main goal; brave the decisions I had made, and as usual a few shots needed adjustments to keep a lighting consistency within a scene.

BC: What was your proudest moment from the production process? Is there a specific scene or shot that you’re especially proud of?

BK: The element of repetition was something I suggested to the director, based on Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. It would introduce us to something out of place from the start. Practically we filmed and would include in the edit the exact same scene, from a slightly different angle. The viewer might think it’s a mistake at first, or “a glitch in the matrix”, but it would make sense in the end – and set the tone for the maze the women are found to live in, repeatedly.

Also, I wanted to remove the POV, meaning that the camera was always objective, and we would never see it from the point of view of the women, including inserts. We would also have segmentations of the women, “cuts” of the female body, as seen in many films or ads.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production that you’ll take with you onto future productions?

BK: Time – you’ll never have enough of it, never. Prepare and test as much as possible in pre-production. An idea is as good (or bad) as it’s executed.

BC: What would be your dream project as a cinematographer?

BK: A near-future goal of mine is to be the cinematographer for a story set in Albania. I am writing it (probably with someone else directing it). I look forward to the challenges of shooting under the Mediterranean sun, or the unpredictable poetic September sunlight.

I, like everyone, have dreams I don’t dare say out loud, yet.

But all in all, I dream of waking up, every single day, to be on set.