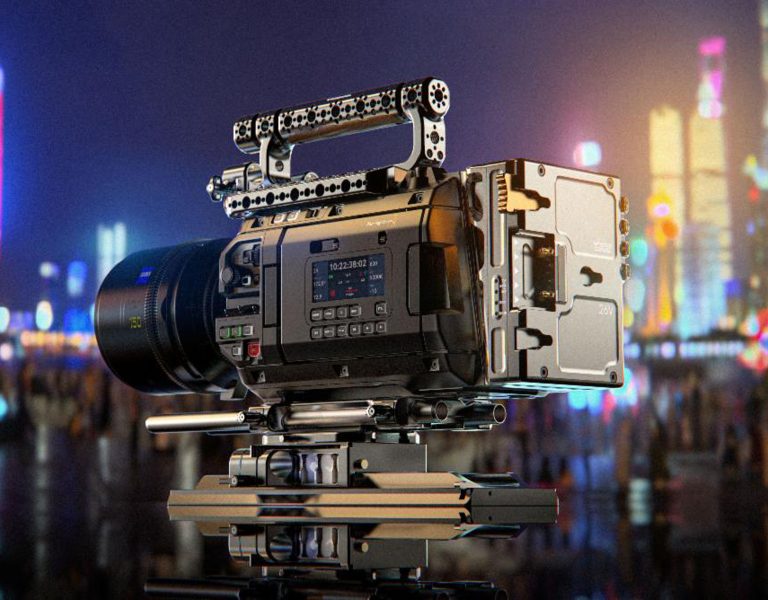

Caroline Champetier, AFC, and Inès Tabarin, 1st AC, talk about the making of the film, filmed with Sony Venice and α7 III cameras, and with ZEISS Supreme Prime lenses.

This article has been shared with permission from ZEISS, and was originally featured on their LENSPIRE blog.

ZEISS: Unlike his previous films, Leos Carax didn’t write the screenplay.

Caroline Champetier (CC): It’s a libretto written by The Sparks. After they had seen the scene using their title “How Are You Getting Home?” in Holy Motors, they proposed the text to Leos Carax. He started working on the songs with them. The music was written, they made adaptations and he wrote the lyrics for some songs himself.

When she appears with her short haircut as Ann, Marion Cotillard reminds of Kylie Minogue’s character in Holy Motors, who already was a tragic singer. Is the relationship explicit?

CC: It’s rather that their common reference is Jean Seberg. It is also a movie about cinema.

There seems to be another, more contemporary reference to the stand-up comedy show given by Adam Driver’s character: it’s the “Netflix Specials”, which are the filmed stand-up performances richly produced by Netflix.

CC: Yes, Leos sent us some. I mostly watched Louis CK’s ones. In the first ones he made us watch, there were red light stains on the audience. One of our challenges was the great number of extras asked for by Leos for the audiences, given that Henry (Adam Driver) and Ann (Marion Cotillard) are superstars. One of his solutions was to place our extras in the light zones, and to multiply an abstract crowd in the shade, in VFX. Leos Carax sends us references which give us a lot to help understand his imagery. He gave them to us technicians, or to the actors via the assistants, and I tried to see everything.

For the opening scene “So may we start”, filmed in the mythical Village Studio and on Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles, the reference was this Californian wedding film, for the urge and the way the guests join the singing group. Most of the time, Leos designed the staging so that the songs were filmed all along in a cinematographic way, which means creating shots that mostly lasted as long as the song. It was about finding a way to write the scenes in few shots, hence a lot of movement. We used different framing tools to achieve the direction.

Did he want to film the music? To make a musical?

CC: We never said neither “film the music”, nor “musical”. With Leos Carax, everything soon becomes a question of manufacturing. The first thing we did was going to puppet shows, notably Giselle Vienne’s ones. One day I filmed Annette’s first mask on a gaff, close to my daughter playing the guitar, to see if the face, which Estelle Charlier had created, worked near a young woman. It happens in attempts, tests, assumptions.

Inès Tabarin (IT): Leos Carax works like a craftsman, which needs research and many visual tests.

CC: During these first tests, the question was if we believed in it, and finding a way to make her sing and move. One of the first things we filmed was her aria, and this great idea from the puppeteers, Estelle Charlier et Romuald Collinet, to have her fly away. We were struck. Leos and I did not realise what is the puppet art, which is a thousand-year-old art. They know how to make something, that looks like a human, move… We thought that we would bring them to us, whereas we went to them, there are no animatronics or VFX. When her face moves, her expressions actually change between shots. At a particular time, the director (Simon Helberg) plays for Annette the love song of her parents. As the camera is isolating the conductor, the puppeteers are changing Annette’s face off screen. Then the camera pulls back: she has fallen asleep. It is only manipulation, for them as for us.

IT: Between the puppeteers and the camera, the shot was always a difficult choreography to elaborate.

CC: It was. We also made tests to find Annette’s skin texture. The propositions were quite different, and the lenses play a great part in the look. Estelle Charlier is the one who draws and sculpts. Romual Collinet puts into motion. We had discussions about the hair, whether it should be real or made of wool… We always see the true Annette on screen, even in the Hyper Bowl scene, which takes place in a virtual stadium. The VFX were mostly used for this scene and to erase the puppeteers, who manipulated the puppet with rods.

In contrast, the storm scene [editor’s note: which is on the poster] is entirely shot live. The storm in the background is made of a front screening on a semi-circular, twelve-meter high, thirty-meter wide cyc hanging five meters away from the boat. Two projectors were broadcasting a surfing wave in a loop. We had to find how to represent the sea, should we see the sky or not… I looked for photographs of surf, pictures from Hokusai or Courbet. Quite soon Florian Sanson, the art director, proposed a picture that made me click, were you could see the deck of a boat facing a tsunami. I thought, “of course, a water wall, why need the sky?” This is when the experience I had with the limousine interior in Holy Motors was useful. It already was a projection system, on which I had great help from Jean-Pierre Beauviala [the inventor and founder of Aaton Cameras], whereas everyone else told me that a green screen was the only solution.

IT: This scene is so organic, thanks to all these attempts!

CC: Leos Carax first thought that we should film the scene close to the characters, so that the camera lives through the storm as they do. However, when I discovered how the gimbal supporting the boat worked, I thought that the camera had to remain outside the boat, because if it were attached to the movement, there wouldn’t be any movement. We had a rostrum built to move the dolly all along the boat, so that we were able to improvise with the actors in motion.

IT: This scene was shot in two days, knowing that the actors had rehearsed with stunts before.

CC: In the opera nightmare scene, where Ann [Marion Cotillard] gets lost in the forest behind the iron curtain of a fake forest, it is a classical green screen. We filmed the scene in a very particular forest in Brussels, where they have species from all countries. It is a day-for-night shooting, both for aesthetical reasons and because it was more manageable, logistically and during the color grading. It was much simpler than shooting at night in October. The production was glad, and it works as well.

IT: It contributes to the strangeness of the setting and to Ann’s inner world.

Do you shoot day-for-night in digital as you did with film stock, with filters, high lights?

CC: Yes, roughly, except that since the shot moves around at 300°, we could not keep the sun in backlight. Digital is useful here to add contrast in some parts of the shot, but I have to say that in the film, the grading almost did not use any mats.

Which tools did you choose to operate the cameras?

CC: There are different framing tools, that are not systematic, which makes the richness of the cinematography. There is Steadicam, dolly, a small crane, handheld camera… We did not settle in a filming system. The motions follow the blocking. Carax quickly talked about using a Steadicam, but we knew that we would not be able to afford a steadicamer every day, we had to adapt. I really enjoy the dolly. There is a sophisticated dolly move in a scene were Marion Cotillard sings about her worries: it is designed, rehearsed with the actress. Many directors can be reassured by a kind of versatility of the Steadicam, but we would not have been able to achieve the firmness of the shot and the way it sometimes freezes with a Steadicam. I find it difficult to block, because it is all about rhythm, how it starts and how it ends… Which is not the case with the dolly.

Jo Vermaercke was a very pleasant steadicamer. He was respectful of the fact that the shot is built by several people. We made a film which looks like it has cost five million euros more than the actual budget, so we had to work as a flexible, hybrid team. Jo also operated a second camera, Inès was focus puller and camera operator, our trainees were also able to operate and to assist…

IT: What I also found valuable on this shooting, and, I think, uncanny, is the accuracy of every department, and their conscience of what the shot should be. Many individuals suddenly become one ecosystem going in the same direction. We were always on the edge, we felt the danger and the fragility of the making of the scenes, and at the same time everyone was committed and knew what they had to do. I think that it is the strength of Carax and Caroline, who provide indications while leaving room for each of us, opposed to other sets where technicians can be very far away from the staging. There, we were both dazzled and extremely focused.

Do you shoot day-for-night in digital as you did with film stock, with filters, high lights?

CC: Yes, roughly, except that since the shot moves around at 300°, we could not keep the sun in backlight. Digital is useful here to add contrast in some parts of the shot, but I have to say that in the film, the grading almost did not use any mats.

Which tools did you choose to operate the cameras?

CC: There are different framing tools, that are not systematic, which makes the richness of the cinematography. There is Steadicam, dolly, a small crane, handheld camera… We did not settle in a filming system. The motions follow the blocking. Carax quickly talked about using a Steadicam, but we knew that we would not be able to afford a steadicamer every day, we had to adapt. I really enjoy the dolly. There is a sophisticated dolly move in a scene were Marion Cotillard sings about her worries: it is designed, rehearsed with the actress. Many directors can be reassured by a kind of versatility of the Steadicam, but we would not have been able to achieve the firmness of the shot and the way it sometimes freezes with a Steadicam. I find it difficult to block, because it is all about rhythm, how it starts and how it ends… Which is not the case with the dolly.

Jo Vermaercke was a very pleasant steadicamer. He was respectful of the fact that the shot is built by several people. We made a film which looks like it has cost five million euros more than the actual budget, so we had to work as a flexible, hybrid team. Jo also operated a second camera, Inès was focus puller and camera operator, our trainees were also able to operate and to assist…

IT: What I also found valuable on this shooting, and, I think, uncanny, is the accuracy of every department, and their conscience of what the shot should be. Many individuals suddenly become one ecosystem going in the same direction. We were always on the edge, we felt the danger and the fragility of the making of the scenes, and at the same time everyone was committed and knew what they had to do. I think that it is the strength of Carax and Caroline, who provide indications while leaving room for each of us, opposed to other sets where technicians can be very far away from the staging. There, we were both dazzled and extremely focused.

How did you hold this sensor block?

CC: I had a sort of buoy attached to me with straps: it is not very elegant [laughs], but it allowed me to rest my elbows and hold on for a long time.

IT: Jo also used the sensor block for one of Henry’s shows. He was sitting in the first row with the camera on his knees, while Caroline was operating the dolly track, back and forth behind the audience.

How did you choose the lenses?

CC: Choosing equipment is always an equation between a look, ergonomics, a budget… The lens blind test I ran with Denis Lenoir and Martin Roux two years ago made me rediscover the Zeiss Super Speed and the Zeiss Standards T2.1. I had not utilized them for years, after having entered the profession with these lenses and used them a lot with Jean-Luc Godard. When I was able to depart from them, I was quite glad at the time… But during this test, I thought, “They are so beautiful on the faces!” Why not take Zeiss lenses? We weighed the Supremes and we took them. I ask that everything be weighed up.

You could have chosen the Super Speeds.

IT: We did test them, but we had scenes that requested large format in 6K, so we needed appropriate lenses. We tried several sets and the choice of the Supremes was obvious.

CC: I think that they are very well balanced on faces. It is mostly due to their optical design. They are beautiful lenses for the faces! We toyed with the idea of anamorphic [to Inès] but I think it would have been too much.

IT: More European maybe… Shooting in anamorphic, we would have evoked the Hollywood machinery, which would have been too on the nose!

CC: Perhaps! And we did something sacrilegious: again, in order to take into account the budget and the constraints imposed to all the crew, we married the Supremes with a small Primo zoom and particularly an Angénieux 25-250 zoom, with which I have been working for forty years.

IT: As we mostly shot in 4K, the surface of the sensor was covered.

CC: What is incredible is to watch, as it happened in the Hyper Bowl scene for instance, is a shot that was designed with a Supreme Prime, and Inès and I with our old 25-250 zoom, filming Adam Driver as he starts to cry and falls backwards. When we saw, in the dailies, how the blacks surround Adam’s face, and are sampled in a totally different way than by a modern lens, we were struck! There is some beauty in the way his face emerges from the black shrouding him. During the grading I often tried to degrade a little bit the sampling of the Supremes. It was to homogenize the images of course, but also to meet the very organic feeling given by these vintage lenses.

I had the feeling of seeing light sources in every frame.

CC: It’s a necessity when you film shows. You know that you are going to have light sources in the camera’s range. It’s the same when you film a bedroom or architecture, not forgetting Annette’s star bedside lamp. However, I had more practical lights in Holy Motors. The limousine was almost only lit by little light sources within the frame.

And these lights sources are surrounded by a halo…

CC: It’s the filters. We wanted to work on the texture.

IT: Indeed, it came with Annette’s face and what she would react to; then we thought of having lights in the frame all the time. Seeing Leos’ references it came quite soon. The filters we used were mostly Schneider Hollywood Black Magic (which live up to their name!), sometimes paired with Soft FX.

Do you think that the texture of film stock remains the reference, or have we moved on?

CC: For Carax it does. He often says, “it’s so crisp, so digital”, which the film isn’t: I find it quite soft. As for myself, I have moved on. Anyway, this film would have been difficult to achieve in film stock, because of the blacks. We had to give texture to the black, we didn’t want to make it frightening, but porous, so that we could enter it, and we had to revive it. That is why colors came quickly, and I proposed the reds and the blues to Leos, while he found the green of the swimming pool. The black could not be the winner, we had to work in contradiction.

What do you call a porous black?

CC: Such blacks are not shiny or photographic. You can see them in Lynch’s films, in Lost Highway. The 25-250 provides welcoming blacks. If your blacks are too shiny, you remain at the door. Such a finesse of the blacks is difficult to achieve with digital. It was the challenge of the film and for the colorist, which I told him right away. The difficulty is not to achieve it once: the work of the cinematographer is maintaining the consistency of contrasts and texture. I hope at least that one can sense the consistency of the black throughout the film. It was its photographic difficulty.

Did you shoot wide open? There is quite a lot of depth of field.

CC: There is pretty much depth of field because Carax likes it and works with wide focal lengths, to embrace the space and the choreography of his blocking. We were not far from full aperture.

IT: On Henry/Adam, we often used the 29mm, for example. In general, we often shot at T2, T2.8.

Did you watch dailies during the shoot?

CC: We did, but Leos did not. Since we have been working together, he has quit watching dailies! I think it has freed him of something, otherwise he always wants to reshoot. Nelly Quettier, his editor, watches the dailies and reports to him. We watched them on a big screen, for photographic reasons.

IT: We received stills from the lab every day, and at the end of the week we would send a selection to Leos. But he did not see moving pictures. At the lab an assistant was grading the dailies.

Did you have a LUT on set?

CC: There was a LUT, which we used again in the final grade, and which tamped down the blacks. It was good because it protected us.

IT: During the tests we saw that the ISO 2500 base of the Venice was more accurate, for its chromatic fullness and its contrast. We designed one LUT for the whole shoot. The only change we made was on the ISO base, for the night scenes (ISO 2500 base) and the daylight ones (ISO 500 base).

CC: We should have had a varying LUT according to the contrast and the darkness of the scenes. I wish the follow-up of the grading had been more constant throughout the production; the freelance status of the colorists is to blame. But the assistant who graded the dailies was amazing, he was enthusiastic, I liked this guy. The lab technicians were wonderfully involved, both for VFX and for the development.

Did you film with the music playing?

CC: No, I did not, it is all live recorded, there is no playback! They are really singing, most of the time. They had earpieces on, whereas I never did. I did a silent movie! I think it is one of the reasons for the drive I had towards expressionism, both in the lighting and in the colors.

And in the closeness to faces?

CC: Indeed. I think that if I had heard the music, I would have been inclined to back up a little… It was complicated for them, music was a big thing on this shoot, and I did not have enough room left in my brain to grasp it correctly. [to Inès] How did you experience it?

IT: In the same way… That is the beauty of working on this film: we became spectators again. When we watched the finished film we discovered it entirely, even though we knew the shots by heart. We were struck again, and it is a beautiful gift Leos made to people who worked on the film.

–

This article has been shared with permission from ZEISS, and was originally featured on their LENSPIRE blog.