Writer-director Ekwa Msangi’s debut feature Farewell Amor premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2020 and was released in December by IFC Films. Msangi describes the intervening months as “a roller coaster,” marked as they were by a global pandemic, social unrest and political turmoil.

“It’s been such an awkward year,” she says. “But it’s also felt very hopeful in terms of changing government and the Black Lives Matter movement and things that people are not willing to tolerate any longer. That includes not having our voices heard in the way they should be. Even at Sundance, it felt like we were moving into a new era, where people are willing to take us more seriously than they have in the past.”

Farewell Amor begins at JFK Airport, as Walter (Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine) is reunited with his wife, Esther (Zainab Jah), and daughter, Sylvia (Jayme Lawson), for the first time since he arrived in New York City, 17 years earlier, from Angola. Walter came to the United States determined to provide a new start for his family following the end of the decades-long Angolan Civil War, but after so much time apart, they may as well be meeting one another for the first time.

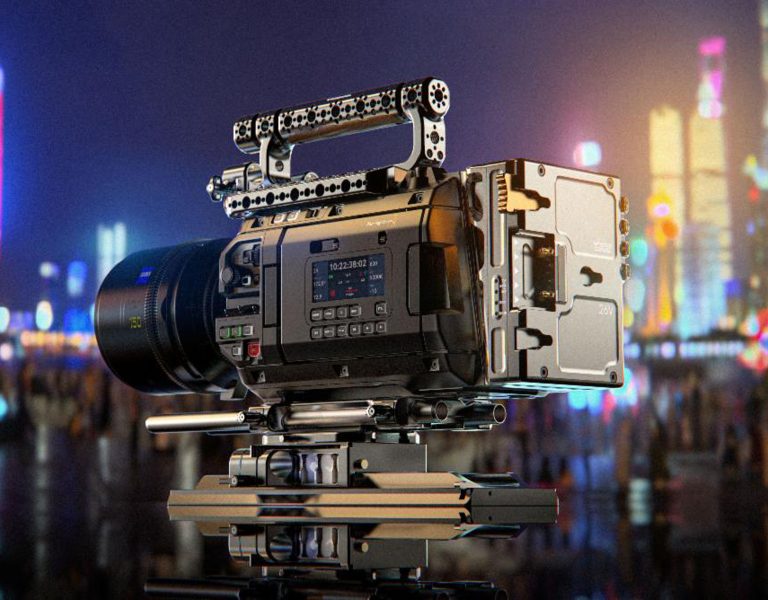

Behind the scenes, Msangi’s collaborators included producer Huriyyah Muhammad and cinematographer Bruce Francis Cole. The filmmakers sourced their camera and lens package from Panavision New York through the use of Panavision’s New Filmmaker Program grant. “I’ve used that grant several times, all for first-time feature filmmakers,” Cole says. “One of the beautiful things about Panavision is that independent filmmakers have access to all these tools that the bigger studio projects are using. I’m always appreciative of getting an opportunity to work with Panavision.”

Panavision recently connected with Msangi and Cole for a joint call over Zoom to discuss the visual language they crafted for the movie. “I’m so pleased with what we were able to do with the film, and Bruce is so masterful in his work,” Msangi says. “To see him getting the love that he has been is so great.”

Writer-director Ekwa Msangi and cinematographer Bruce Francis Cole.

Panavision: When did the two of you begin to discuss Farewell Amor?

Ekwa Msangi: Preproduction started on a Monday, and we met the Thursday before. We were initially slated to work with a different DP who had to drop out at the last minute, but he said, ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to introduce you to someone good.’ I think that was Tuesday, Bruce read the script on Wednesday, and then we spoke for the first time on Thursday. I don’t know if I told you this, Bruce, but one of your references was a good friend. We had gone to school together, and when I called, she said, ‘Just hang up the phone and hire him immediately — it’s the best thing you’ll ever do in your life!’ And I was like, ‘Okay, I guess I will!’

Bruce Francis Cole: I am so appreciative of Jackie Stone’s referral — I’m sure that’s who that was!

Msangi: How can you tell? [Laughs.] So we took a chance on each other — because Bruce didn’t know us, either. We started preproduction, and we spent that whole week, sunup to sundown, mapping out the entire film and talking through what I saw, what I felt, and what was important to me about the story.

Cole: Like Ekwa said, I interviewed on Thursday, found out on Friday, was on a plane by Sunday, hit the production office on Monday morning, and we had two weeks before we shot the film. [Laughs.] We share a lot of the same friends, though, and we both were familiar with the aesthetic of indie and foreign cinema, so in terms of language and shorthand, it wasn’t a stretch.

Were there any particular films that inspired your approach?

Msangi: We looked at Andrew Dosunmu’s work, like Mother of George, quite a bit because he’s an African filmmaker telling stories about Africans in New York. And Bruce has a much bigger vocabulary as far as artwork and cinematographers and films. We ended up talking about Wong Kar-Wai and who else?

Cole: You had a really cool reference, the dance film —

Msangi: La Tropical, a Cuban dance film. That’s true.

Cole: Coming from the continent of Africa and being very familiar with African cinema, Ekwa had a lot of references that we pulled from in terms of the feeling and the rhythm of the culture, and what our characters were leaving behind, and what they were trying to rescue here in America. The semba dance scene was a big motif for the film in terms of how the characters move within a space and with one another. We wanted to mimic that rhythm throughout different parts of the film.

There are a couple scenes in the film — and I don’t think Ekwa even knows this — where I was placing very particular items in certain places of the frame to call back to Ming-liang Tsai’s film What Time Is It There? With a lot of his films, it’s dramatic material, but you don’t necessarily experience it with a lot of editing. It’s a lot of still frames with characters moving in frame. We were inspired by that, and then filmmakers like Andrea Arnold and Lynne Ramsay and a lot of contemporary coming-of-age films.

What led you to frame for the 2.39:1 widescreen aspect ratio?

Cole: We wanted to play the background mise-en-scène because the story isn’t just about the characters. It’s actually about the characters within an environment — within the small apartment, within New York City. We knew we always wanted the setting in the background to be a part of the characters’ lives. I think it was instinctual, just knowing that the background is supposed to be a fourth character in the film.

The film is structured as a series of chapters, one for each of the three main characters, and each is demarcated by its own visual language in regard to the camerawork. What were the techniques you employed to distinguish one section from the next?

Cole: We relied on the camera and framing because any other choices would have required a bigger budget, which we didn’t have, or more control, which we didn’t have. For the first chapter, Walter’s story, we incorporated wider focal lengths — the 17.5, 21 and 27mm Close Focus Primos — and we photographed with the camera on a tripod or dolly from a distance to keep the characters somewhat emotionally detached. When we needed a long lens, we would shoot with the 40mm Primo.

The second chapter, Sylvia’s story, was photographed mostly handheld and up-close with the actors. We wanted the camera to feel immersed within the environment and the characters’ personal space. We used the 27mm and 35mm Close Focus Primos along with the 65mm and 85mm Primos — I like to use focal length to control depth of field. If I decide I want to have less depth, I will typically shoot longer, and vice versa. We used the spherical Primos for chapters one and two so they would share the same texture, because Sylvia and Walter start to develop a connection. These chapters are a little more clear, sharp, vibrant and full of contrast than Esther’s chapter, which has a softer, dreamier palette.

We wanted the third chapter to feel very subjective and romanticized. We decided to shoot with longer Cooke Panchros to try to keep the frames detached from one another, and we really utilized the language of montage and close-up. We had a lot of frames with Esther that were isolated micro stories within the macro, so we could juxtapose images and create a different idea of the bigger picture. As we get deeper into the chapter, the focal lengths get longer and the frames feel more impressionistic. We also incorporated filtration to really present the fantasy that Esther was experiencing mentally. Finally, when all the stories collide, we combined all the lenses and visual languages, and we stripped back the filtration to present a more raw and honest presentation of the story at hand.

So much about the state of the relationships between the characters is expressed through the framing, particularly in the use of negative space and short-siding the actors. Was that all determined during preproduction, or was it more instinctual as you were filming?

Cole: Almost everything was thought out beforehand. We had to figure out exactly what we were going to say and how it would fit into each chapter’s particular language. We pushed that aesthetic, and we made sure to keep it, because it’s very easy when you’re under stress to forget about it and go to rudimentary concepts and ideas instead of really trying to lean into the subjective language that you want to use. So we knew exactly what we were doing with every frame.

Msangi: We had to. We had a very limited budget and very limited time in our locations. We also had very tiny locations! [Laughs.] That apartment was as small as it looks and feels. I remember Bruce being like, ‘Oh my god, how do we make this look interesting so that we’re not just doing this and this the whole time?’ Because there literally were two places that we could shoot from.

Cole: At the end of the hall or at the beginning of the hall! [Laughs.]

Msangi: Right! I’m so impressed that we were able to make it seem as interesting as it is given the limitations. We didn’t storyboard, but we did have shot lists for everything, and I had drawn little squiggly diagrams on the script for where the camera would be. There were some surprises and some moments of working on the fly, but it was always within what we had envisioned because we had talked so thoroughly about what it was that we wanted to see or the effect that we wanted to create.

Cole: We wanted to be really deliberate. It was about revealing information as opposed to just covering the scene, which meant there was a defined place where the camera wanted to be. Our baseline would always be some sort of feeling, usually described with an adjective, that we could hold onto and take with us. Then, if some part of our plan failed, we would always have that word to return to; if we had to make a decision at the last minute, we would still know the truth of what we were trying to reveal.

In Sylvia’s chapter, there’s a scene in the apartment kitchen, where Esther is cooking while Sylvia’s on the computer. The scene begins with a shot-reverse-shot pattern that keeps each character in her own frame, but at a certain point, the camera begins to pan between them, connecting them in the same shot.

Cole: There were two times in particular we wanted to do that panning technique, in the kitchen and at the bus stop when Sylvia’s talking to DJ [Marcus Scribner]. It’s a subtle technique that shows the connection between two characters. It’s about the rhythm between both of them and how much they’re communicating or not communicating with one another.

Msangi: It’s like the camera is dancing back and forth between them.

Cole: You’re putting the audience, for a moment, back into their own perspective, trying to figure out who they want to go with, as opposed to being in the perspective of one of the characters. You lean on the operating because at some point you’re choosing to not show something and to focus on something else instead.

Blue light is used as a fill or sidelight in the apartment, shaping the actors within that space and adding dimension to the very close quarters. How did you conceptualize the use of color in the lighting?

Cole: Oh boy.

Msangi: [Laughs.] He fought really hard for that blue light!

Cole: It was my secret homage to What time Is It There? There was a fish tank inside of the small apartment in that film, and I always remember how that one light source gave off such a presence and changed the space in the apartment. When we were prepping this, I was thinking, ‘How am I going to get something different in this space that makes sense — another color that can evoke a different kind of mood?’ So I said, ‘Hey, can we get a fish tank?’ And everyone was like, ‘Well, I don’t think he would have any fish.’ And then someone said, ‘I don’t think PETA is going to let us have a fish.’ So I said, ‘Well, can’t we just have the fish tank?’ And they asked, ‘Why would we have the fish tank with no fish?’ So it became this thing, but finally I got my wish.

Msangi: I remember there was a period when production was like, ‘Do we really need this fish tank?’ And I said, ‘All right, I’ll talk to him.’ And I asked Bruce, ‘Do we need this fish tank?’ And he said, ‘Yes, we do,’ and I told production, ‘We need the fish tank!’ But we had watched some clips from that film together, so I had an idea of what you were going for.

Cole: I wanted to add contrast to what normally would be a warm palette with the sodium-vapor lights coming through the window. Anyone living in New York knows you’re going to get that light shining in your window at nighttime — there is no moonlight in a New York City street. So I wanted to have something to contrast that, especially in relation to the dynamics of what was happening in the apartment. There are certain moments in the film when it really plays, and whenever you see one of our two angles — the beginning of the hall or in the kitchen, looking back through the hall — I’d try to use that light to break up the space as characters walk through. That blue color ended up playing really well.

What did you use to supplement the light from the fish tank?

Cole: Because of the budget, we actually just ordered some tunable RGB LED strips off of Amazon, and then we rewired an old fixture from the art department with our LED strips. I gave them a blue-cyan to mimic mercury vapor. I wanted to add something that felt natural, so the idea was that it was a mercury-vapor-lit fish tank. The LED strips weren’t perfect, but they’re light years ahead of where we were 10 years ago in terms of having that much control.

In the film’s opening scene, Walter says, ‘Look at this … you are here!’ And at the end of the film, Esther says to Sylvia, ‘We see you. We do.’ Those lines bookend the film and underscore the importance of seeing one another — and seeing stories like this onscreen. What does it mean to each of you, both personally and professionally, to have been able to tell this story?

Msangi: It means a lot. I don’t take it for granted at all that we managed to get the money to make it, that we managed to get the reception that we did, that we managed to sell it. Because I’ve tried for many, many years. I grew up in East Africa, and that’s the inspiration for a lot of my stories. I’ve been trying for many years to get films funded about Africans or African immigrants to no avail. The reception has always been that unless it’s a big issue, like struggling with some horrible law or child soldiers or something like that, nobody’s really interested because they feel like they can’t market it. So just as a personal hurdle to overcome to be able to get people to believe in this story is huge. And to have made the movie with the team that I did means a lot to me.

Cole: One of the interesting things about the bookends is that in the beginning of the movie you see all three of them together in the frame, and then you don’t see all three of them in the frame together again until the very end. Sylvia’s never with both parents at the same time in her chapter, Esther’s always by herself in her chapter, and Walter’s always coming in and out in his chapter. So we said, ‘What if we just keep them apart until the final scene, where they all finally see each other?’

For me personally, I really appreciate the fact that I got to tell a story in this particular way, in a way that’s independent in its voice. Oftentimes when you see characters that look like me, they don’t necessarily get the three-dimensional visual storytelling that we tried to present with this film. And then to display on such a big platform at Sundance and IFC has been a beautiful experience. I so appreciate it.

All images courtesy of IFC Films. Article courtesy of Panavision.