A PAINTER’S EYE

Why should cinematographers looking to produce unique creations seek influence from centuries-old art? Witold Stok BSC explores the powerful influence paintings can have on filmmakers.

In cinema’s multi-rooted parentage, painters, poets, novelists and theatre animators line up with engineers, craftsmen, builders of medieval cathedrals or the creators of mass-produced Bauhaus works. 17th century Italian opera welded together music, movement, drama and stage illusion, resurrecting ancient Greek drama’s sense of universality. Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk idea of ‘total artwork’ – integrating music, acting, visuals, scenery and more, to mesmerise large audiences through a rush of emotional charge – surrenders to the power of fiction and, at its peak, challenges viewers’ minds.

The cinema spectacle picks up from the opera and, later, the music hall experience of our ancestors. Motion relates film to other performing arts. Much of what happens on stage, superficial and yet paradoxically alive, goes on in our yard – the reality of space, the mise-en-scène, the pivotal presence of actors as characters, music, visual creation, and drama. Cinema-makers gradually learned the ropes of proper storytelling, mostly from literature: the plot-driven narrative, the play of cause-effect, the action-in-time factor. The novel’s chain of events became film editing. Literature, as novelist EL Doctorov points out, “gives to the reader something more than information. Complex understanding – indirect, intuitive and non-verbal – arise from the words of the story.” Film amalgamates these pursuits of beauty and expression, bringing inherent energy to our much younger medium.

“A painter can be interested in fine arts only. A composer may sit exclusively in music. But a filmmaker simply must be interested in art. And not just because something from one of the other art disciplines might prove to be useful; a filmmaker must think about cinema as art. All the muses are older than the films, and so it fits to listen to what the ‘council of elders’ has to say. Concentrating exclusively on film leads to the involuntary copying of the language, and a copy will always lack what’s most important: its own feeling. There is no use learning film only through films,” according to director Andrzej Barański.

Director Jean-Luc Godard reminds us that cinema, born along with public transport, took us closer to events rather than just to places. “Film draws upon and sucks dry all the other arts,” said film critic David Thomson. The usual insults follow – too literary, too painterly, too stagey, too operatic. A reproaching epithet ‘theatrical’ damns a film for missing the vital connection with reality.

The connection with the art of painting – our closest relative, a much older sister, almost mother – is different. We don’t directly compete, yet secretly aspire to be like her. There is no immediate danger of losing our identity but, rather, a promise of nurturing. “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were to Wordsworth,” confessed poet Philip Larkin. Instead of deprivation and daffodils, directors, costume and production designers, and cinematographers talk and write about contact with inspiring paintings.

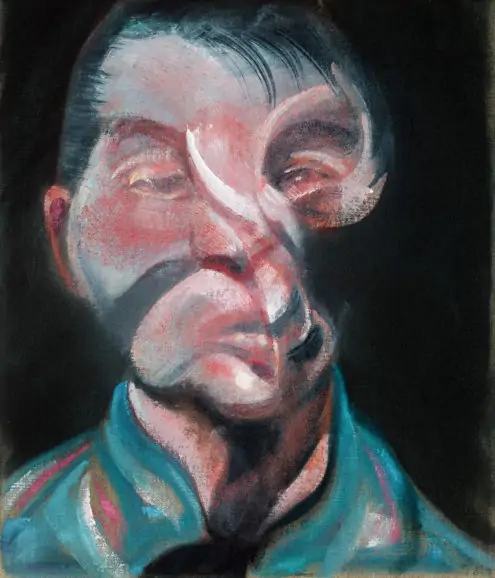

In the urge to speak now, in one’s unique voice, why drag from the past the heritage of centuries-old “dead art”? Fernando Meirelles, of City of God fame, answers: “Sometimes we want to dynamite the Louvre and try to create something from nothing, but sometimes all we want is to talk about the simple facts of life.” Both painting and film work through appearances, vitally linked through the physiology of seeing and reception. Ours is a mechanically based medium and yet often strives to imitate living reality. Flowing through visual expression, painting’s power guides us on how to notice deeper layers of reality. Robert Bresson said: “Have a painter’s eye. The painter creates by looking.” Christopher Nolan’s Inception dream sequences borrow from the impossible architecture of MC Escher as well as from Francis Bacon.

“You have to look to art to teach you and guide you in terms of expressing things beyond dialogue. I quite like the paradoxical nature of it. The more he removes, the less he tells you really about what’s out there, the more I find myself thinking about what’s in that dark space behind… You never have the resources to fully create the world that you’re creating, so you are leaving a lot of voids, leaving a lot of gaps. So, part of what you’re trying to do is using those necessary gaps intelligently, so that where you’re not showing something, it’s helping you rather than feeling the limitations of the world you’ve created,” said Nolan.

When speaking about The Dark Knight and actor Heath Ledger’s portrayal of Joker, Nolan commented: “One thing Heath wanted to do was to apply makeup himself. As an actor, he said, ‘Ok, this character would put his own makeup on in real life, so what would that look like if I just got the makeup.”

Architecture and sculpture deal with three dimensions. Representational paintings condense the entire story of three-dimensional reality in a two-dimensional image frozen in time, with the suggestion of depth to project spatial illusion. With the same relevant intuition of the eye, films construct a story as a series of images within four-dimensional space-time, the fourth dimension being time. Until (and if) we switch to 3D, transforming the world into a two-dimensional image is one of the basic points of our pictorial work. Still, perhaps the most important to the storytelling, yet unquantifiable, beyond any stereometry, is the dimension of human emotion.

The painters from the 16th to early 20th centuries pulled the visual strings of storytelling close to ours, creating an inspired representation of the world that is also its corrective, not merely what it ‘is’ but an expression of what they saw and felt. Their inroads into formal inventions to evoke emotional reactions in reception fascinate. Their observation of the effects of light phenomena in nature used as a dramatic element was revolutionary: the graphic expression and narrative qualities of light, its mood-creating direction and contrast, colour and temperature, the power of the mystery of shadow, soft or hard quality, high and low key, the distribution of highlights. They perfected the effective tools to direct the eye: spatial perspective in setting foreground against the background (using proportions, golden ratios, diagonals, verticals and horizontals), patterns and various shapes to underpin the strengths of composition, contrasting textures, intensity and contrast of colours, the impact of their psychological associations like setting red against opposing green or cold against warm, the degrees of colour saturation and monochromatic schemes.

“Don’t kid yourself. We’re all of us guinea pigs in the laboratory of God. Humanity is just a work in progress,” said Tennessee Williams. Painting relied on a knowledge of myths, legends, and religious tales. It occasionally flirted with the inclusion of a word or an inscription within the frame, just like captions propped silent movies. These cutting-edge storytellers explored the same crucial narrative dilemmas in the psychological workings of seeing and forming an expression of images, often revealed with a concise impact. Many of them would now be in the visual mainstream, art house and independents.

Most of the image-making techniques that moviemakers “discover” were exercised throughout the centuries, sometimes through proto-film techniques. Painter Paulus Potter seems to employ shading to accentuate a tempestuous feel, which looks much like an effect of graduated neutral density filters applied diagonally in opposite corners of the frame. Why prise open an already unbolted gate?

Exploring painters’ secrets opens out a chance to deepen and enlarge the filmmaker’s scope of visual solutions to ensnare the spectator. The clichéd cinematographic expression ‘painting with light’ still carries some truth. Yet the cues and clues from paintings don’t always have to propagate the tired stereotype of “painterly” lighting but to learn from painters’ storytelling. Lighting a film is more about sculpting with light. I often look for visual inspiration elsewhere too – stills, war reportage, architecture, even dance or opera.

Measuring up to the older siblings, we want and need to be telling the story on our own terms, not overindulging in one particular ingredient at the expense of others. Influence can enhance a work through fertilisation or poison by contagion, but ignoring this enriching legacy of our forebears would be short-sighted. In self-interest, from sheer narrative curiosity, we should not allow it to fade away from memory. When making pictorial choices, lessons in manipulating the viewers’ imagination can be fruitfully quarried from this mine to lead us forward.

In some ‘platonic space’, great works of art from all ages exist, simultaneously echoing and borrowing from each other. In Greek, icon means likeness or image. In the Christian Orthodox Church tradition, the icon mediates in a spiritual heaven-earth connection between the depicted holy figure, the iconographer-painter, and the viewer. Creating an icon involves fasting, focused contemplation and prayer. Creating film images may involve excessive catering, a rush to meet schedules and lots of distractions. Still, in The Acts of the Apostles, the name of the town Iconium appears. The City of Images, quite a place for pictorialists, or should it be pictorians or pictographers? St Luke, the proto-cinematographer, icon-maker evahngelist (patron saint of painters as well as physicians) would be filmmakers’ President there.