UAVs, 3D Cinema & Plasma Lights

GBCT News / John Keedwell

UAVs, 3D Cinema & Plasma Lights

GBCT News / John Keedwell

The BSC show was crammed full of great kit and inspirational ideas, in particular the use of aerial shots with helicopters, microlight aircraft and drones (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles/UAVs).

Each has its place and does specific jobs the others cannot achieve. A helicopter can fly higher for long times and can hover, a microlight is less expensive but cannot hover, and a drone can fly into places the other two cannot. A drone can also be carried as portable kit on a documentary or in a remote location and brought out to be airborne with little set-up time.

The possibilities for drones have never been so exciting, with shots available to the DP and director never before possible. For example, starting the take inside a building, flying out of the window and high up into an overhead and seeing all of the building all in one shot. The drone camera has certainly captured the imagination of many budding aerial cinematographers, and in the excellent movie Lion there was a combination of helicopter and drones used for different areas of the film.

Picking the right tool for the job is essential to make the shot happen in any area of filmmaking. So why stifle the creativity of the DP by holding back on the equipment or tools they can use? Of course, budgets play a huge part, yet if the use of a drone or helicopter elevates the visual elements of a film to a higher level, the audience will be more involved and the story will be told in a visually compelling way. Lion had a $12million budget (source IMDB), so I would say there was a great use of using the tools to suit the task to tell a story really well.

Lion is one example where overhead shots play a huge part of the story, and where they add to the film narrative in a beautiful way. Clearly Peter Beeh, the aerial DP on Lion is an aerial specialist and, along with expert drone operators, a huge part of the story was told from the air. Without those tools the film would have a different look and feel, and perhaps it would not have been quite so successful.

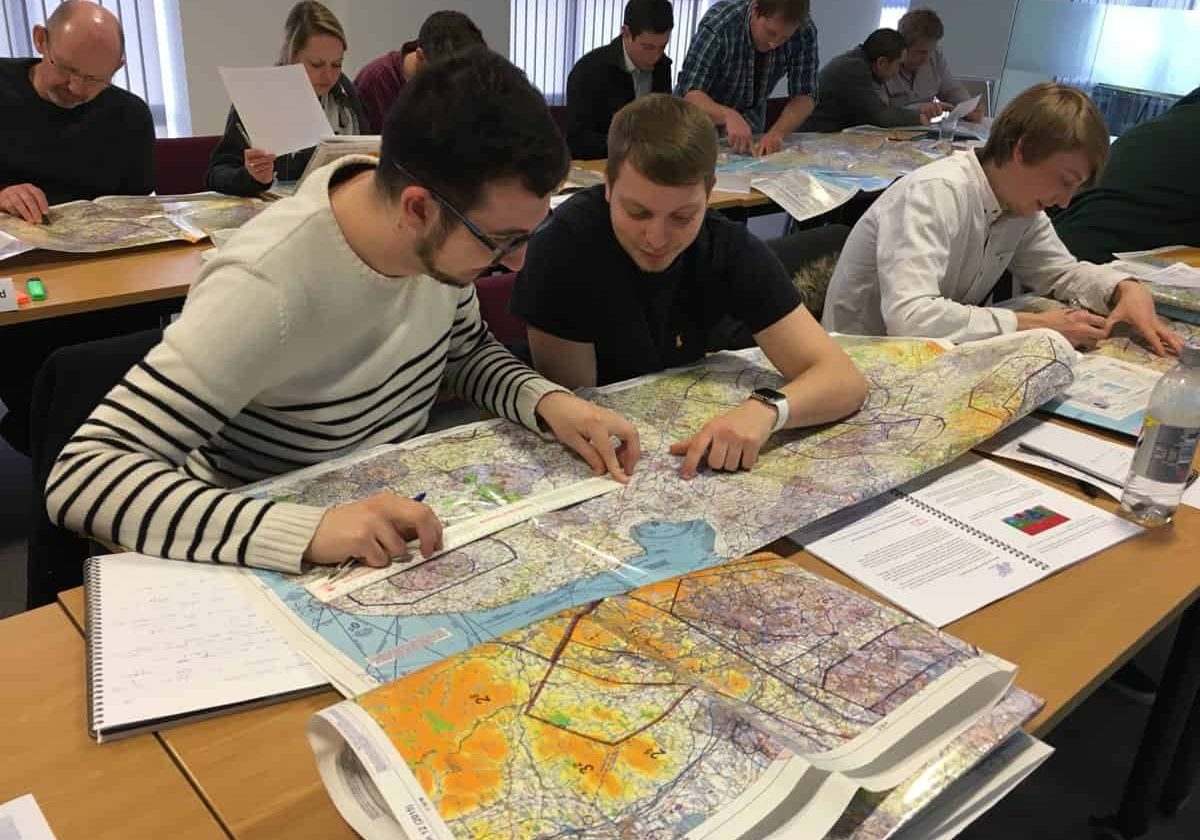

The use of drones for moviemaking has been accepted as a useful tool for specific shots, so it is clearly essential to employ trained and experienced operators who are certified and insured. In fact, it is essential. UK law states that anyone who wants to fly a drone for commercial work (referred to as ‘commercial operation’) must have a permission from the CAA, the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority. To date there are around 2,450 legally-certified drone operators in the UK, although many will not be shooting for high-end moving pictures, they will be making stills for property or engineering surveys, for example.

It cannot be understated how essential training and experience are, and guidance through the rules and regulations is vital. A drone is susceptible to weather conditions such as wind and rain, cold weather and more. So it is wise to understand the limits of the craft you use to safely fly around people and property.

It is essential to get the finest training, and the ability to pass the UAV pilots licence means you are fully-legal and your insurance will be valid. This legal requirement for commercial work is compulsory, and rightly so, as a drone can cause huge potential damage or death if falling on someone, or flying into them. The laws are strict about how far away people need to be on take-off and landing, and also how close the drone can get to vehicles and population.

The laws are about to change and potentially become much tougher to achieve. There is a consultation going on in the UK government right now to determine the future test requirements needed to fly a commercial UAV vehicle. This is where the CAA-approved UAV pilot training is essential, and one of the very best courses is Cambridge UAV Academy’s UAV pilot training course. No matter the size or complexity of the drone, a licence is required for commercial work.

3D Home Cinema

The recent UK announcement concerning the total halting of production of 3D TV's came as a shock to some, but not others. 3D for home TV viewing was always going to be a hard sell, as the viewer needs to wear 3D glasses at home to experience the full 3D experience.

Whilst this is an acceptable practice when going to see a movie in the cinema, it's a different experience for the home viewer. At home the ambient light levels are higher, with room lighting enabling the home viewer to see each other and have an interaction with the family. They can get up from the seat and go to get food and drink without fear of tripping over their dog or cat. Wearing special, expensive, interactive glasses to see the 3D effect is also required, so there is a limitation on how many glasses are available and also limits to optimum viewing angles.

The situation in a cinema is very different, of course. The viewer may buy a huge bucket of popcorn, hot dogs, slurpy soft drinks and other noisy confectionary before they sit down to watch the movie in relative verbal silence and almost total darkness, other than the bright green illuminated exit signs. They can wear their glasses in total darkness and discussions are much less animated than watching the TV at home. It is a more intense and immersive experience, on a much larger screen and with a more intensive sound system than is possible at home.

This demise of 3D home cinema is possibly how curved screens will also go, as the optimum viewing point is right in the middle of the screen, and anyone either side of that position is in less than optimum viewing position. Reflections also cause huge problems on curved screens as it effectively reflects most of the room back at the viewer.

I hear you ask, "Why is the lack of 3D TVs and curved screens so important?". This ultimately will have an effect on how many future productions are now produced in 3D, and this will undoubtedly affect the camera crews who have made a business out of specialist 3D image capture. I know of specialised 3D rigs used for major productions that will continue to develop, yet the DVD after-sales will ultimately determine the viability of 3D productions in the future.

Some films are a spectacular visual experience when shown in 3D, such as Avatar or Gravity for example, and there are more that work. They work well at the cinema, and not so well at home, for the reasons given above. At the end of the day a good story that is well-told will always be more successful than a mediocre story in 3D. It seems the 3D curse has struck again. Even though the technology is vastly improved since the 1950s, it still cannot shake off the perceived novelty value.

"The efficiency of the plasma light is perhaps the most spectacular feature, as 75-80% of the power is transformed into light. This compares to only 10% of the power turning into light for the humble incandescent light bulb."

- John Keedwell

Plasma Lights

One thing that really caught my eye at the 2017 BSC Expo was the sheer volume of companies making LED lighting in one form or another. Of course, some manufacturers are making high-quality lamps that render skin tones really well on camera, and have a high frequency to enable shooting at higher frame rates without flicker. Others are concentrating on the possibility to change the colour output to any one of two million colours. Many are now accurate Bi-colour between 3,200K and 5,600K, dimmable and with only a slight colour shift.

Some other low-priced lamps are found at the lower end of the quality spectrum and have less rigorous standards for colour accuracy when seen by cameras. Some are quite inaccurate, as LEDs are known to have a spiky colour spectrum. Some LEDs flicker at high-speed camera frame rates, and some are decidedly inaccurate in terms of all the above criteria.

The advantages of LEDs are numerous. Low heat, low current draw for a great deal of light, plus they are lightweight, portable and the bulbs don't blow. Yes the features now found in LED lamps have shown truly spectacular advances since the early days, and now there are many on the market. It seems making LED lights is quite a tricky and difficult business to get right.

Then, I saw a plasma lamp at the BSC Expo and it was immediately interesting to me. It demonstrated a very flat and clean, accurate colour spectrum very close to the output of sunlight, no flicker at any camera speeds, high-output, light weight head, small point source bulb, low heat, the bulbs last 90,000 hours+, with low current draw and the ability to move and re-strike quickly even when they have been running for a while. Four lamps can be used simultaneously from domestic ring main sockets, so high-speed cinematography can be achieved in the comfort of your own home! It seems a good many boxes get ticked compared to many other forms of light such as HMIs.

The efficiency of the plasma light is perhaps the most spectacular feature, as 75-80% of the power is transformed into light. This compares to only 10% of the power turning into light for the humble incandescent light bulb, the rest turning into wasted heat. I did overhear a conversation recently from someone complaining studio shoots used to be nice and warm, but since LEDs are used its now so cold in the studio they had to wear a jumper and a coat to work! Think of the polar bears!

At the moment the Gavolight appears in a par form and, with the results I saw with the high-speed camera from Green Door High Speed, it would appear a great innovation in film lighting. I am sure many of you will find the possibilities useful.