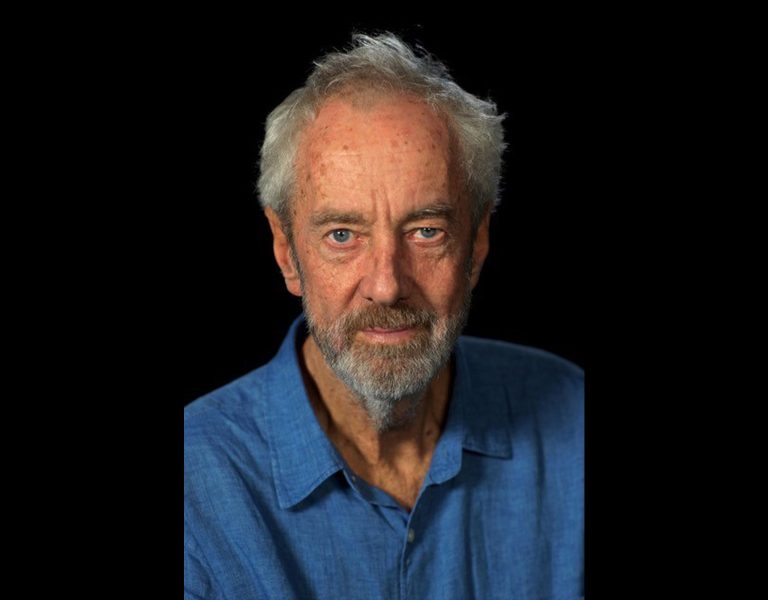

REMEMBERING A MASTER OF HIS CRAFT

Some of those who worked with and knew Dick Pope BSC share words of tribute about a treasured talent, collaborator, and friend.

–

“Dick was a blessing. Some film directors happily change cinematographers from film to film, and many simply specify their basic requirements and leave the cameraperson to get on with it. But for me, the continuity of Dick’s and my joint artistic journey became essential.

We had a great rapport both on and off set. We were on the same wavelength. We shared a hatred of pretentious, unmotivated, gratuitous camerawork, always believing that the camera should serve the action, but also that the actors should serve the camera.

He had such dry sense of humour. He could be wryly curmudgeonly, but in a way that no-one would ever feel offended by. He was brilliant with actors and actors loved working with him. Dick had an instinctive understanding of the integrity of their work and this resulted in relaxed and confident performances. Similarly, he earned respect from his camera and lighting crews; his gentle but firm commanding skills meant that his teams were always a delight to work and spend time with.

After I’d created the action on the location, Dick and I would watch it together, and refine and define it, shot by shot, through the camera. Always on the same wavelength, we made our shooting decisions in total harmony. The final ‘look’ of a movie is very much in the hands of the cinematographer, and Dick’s skills at this stage of post-production were those of a consummate artist. To sit with him in a grading session was always a revelation and a joy, and his final results were a privilege to share.

I will miss Dick for his passion for life, his impeccable good taste, his healthy anarchic outlook, his dry sense of humour, and for our shared passion for all things gastronomic, especially Chinese restaurants and oysters.”

Mike Leigh, director

“I met him on the shoot of The Illusionist in Prague and was immediately enamoured. I already held him in enormous esteem because of Vera Drake and Topsy-Turvy and so many other wonderful films with Mike Leigh, but to see him work the magic he did on Illusionist with such economy of effort and no fuss made me realise how rare he really was.

When I saw Mr. Turner and then ran into him on the award circuit I said, ‘You shot that on film, didn’t you? Super 35.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘The Alexa with my own set of old Cooke Primes.’ I said, ‘If you shot that film on digital, you are underpaid.’

‘I agree,’ he said, laughing.

So I desperately needed him to shoot Motherless Brooklyn and he gave me one of the most joyful creative alliances of my career by saying yes.

He stayed with me in New York for 10 days well before prep so we could pore over books of Saul Leiter and Vivian Meier photos and build plans for special shots. We ate at the same Thai restaurant every night because he loved it so much.

The shoot was cold as hell and the daylight was short. He was utterly unphased and he liked the low winter light. When I had to be on camera too, I often looked over at him after takes and if he pulsed his bushy eyebrows up at me and popped his eyes I knew I didn’t have to check playback. His discernment for all aspects was so impeccable.

I truly loved watching him assess things in the morning and then set about making it look sensational. The tall gaunt frame and penetrating gaze. He was our Gandalf.

Warren Beatty and Francis Coppola later grilled me about the film, guessing it was an 80-day shoot. When I said ‘46 days,’ Warren said, ‘Don’t joke with me, I do this for a living. How is that possible?’

I said ‘Dick Pope.’

The Pope of Brixton. I dearly wanted to do another one with him.

I will miss him terribly but will hear his voice when the light shapes up beautifully and I’ll smile.

Truly he was one of the all-time greats.”

Edward Norton, director (Motherless Brooklyn)

“The members of the BSC and the wider cinematographic community were deeply saddened by the passing of Dick Pope BSC in October. Dick was an incredible voice within global cinematography and brought a uniquely sensitive and emotionally intuitive vision to his films.

In a career spanning six decades, Dick’s body of work was expansive, eclectic and deserved to be celebrated. His remarkable partnership with director Mike Leigh began by capturing everyday English families with realism and deep emotional integrity, evolved through the visceral and politically combative dramas of Peterloo and Vera Drake and matured with Academy Award and BAFTA nominations for the painterly compositions and imagery of Mr. Turner.

But less well-celebrated was the man himself, quietly content to position himself behind the lens and the work. You will find alongside this piece many tributes from his collaborators; directors, performers and fellow cinematographers… those who lived the experience of creation alongside him for so many years. Here you will find the true source of the accolades; the kind-but-frank, humorously-serious, determinedly-curious personality behind the images.

Over the years Dick was a frequent visitor to Camerimage Festival in Poland, as many cinematography-philes find themselves. He was awarded the Golden Frog for Best Cinematography twice in his career (for Secrets and Lies and Vera Drake), the only British cinematographer to receive this distinction. It was at this event in 2016 that perhaps serves as the best reflection of Dick as an artist and cinephile.

Crestfallen at the death of one of his heroes, cinematographer Raoul Coutard AFC, Dick wrote, ‘…viewing the films Raoul photographed was like seeing for the first time, a completely new experience, an explosion of new ideas and techniques, a cinematic revolution. Armed with the new and exciting lightweight 35mm Cameflex Eclair, his was a ragged, but incisive restless camera, a vibrant and carefree shooting style like no other… In many ways he was the French New Wave and I can’t imagine those indelible films or indeed the 1960s themselves without Coutard behind the camera. His influence in what followed, in what happened next, was enormous. His disciples went out there and changed cinematography forever.”

Dick Pope BSC was one such disciple, and he changed cinematography for the better. With an unwavering eye for the truth behind an image, with a casual disregard of the rules and with an open heart to confrontational emotion. Dick was an essential part of the British New Wave for the past 40 years. Like Raoul Coutard before him, the influence of Dick’s filmmaking skill is immeasurable, and continues with his latest collaboration with Mike Leigh, Hard Truths, in cinemas now.

We are the proud disciples of Dick Pope BSC.”

British Society of Cinematographers

“When I was preparing to make my movie The Illusionist, Dick Pope was the first DP I thought of. He’d done Topsy-Turvy which takes place in a similar world, but it was Vera Drake I was really focused on. It’s a beautiful movie of course, but it was the way Dick lit the actors’ faces that completely sold me. Instead of hard lines and contrast, there’s a warm glow that illuminates their humanity with a kind of soulful… buoyancy. And that’s what made Dick so great: he was so tapped into the human, to the humanity. He saw the story and characters with such feeling and was able to translate that expertly into light and composition. He was also extremely funny and hugely fun – the best person to have on set with you. We just laughed all the time.

The Illusionist was supposed to look like an autochrome with a flickering hand-cranked quality. Dick knew exactly how to get that, but it was complicated. And so, we’d be composing these shots, fussing over the visuals, the look… but then he’d turn to me and say, ‘Time to get in there on the eyes, don’t you think?’ Always going for the heart of the human. I will miss him.”

Neil Burger, director (The Illusionist)

“Dick – what can you say? It’s impossible to find the right words. Dick was a force of nature. He was passionate about his work and about life. He had a wonderful, bizarre sense of humour and we shared many laughs with him. He was probably Roger’s longest lasting friendship spanning from the 1970s. He had a great curiosity and was always interested in learning and trying new things. If you ever met Dick, you wouldn’t forget him. We certainly won’t.”

Team Deakins (Roger Deakins CBE ASC BSC and James Deakins)

“Everyone should have a Dick Pope in their life. I had the privilege of working with him for five films. His collaborative approach and advice made me what I am today. I owe a lot to him. He was a character on set and off set, and became a great friend. I will miss him.”

Peter Marsden, cinematographer and DIT

“I write this with a heavy heart – still in a state of disbelief that Dick is no longer with us.

I’ve spent 34 years of my 40 plus years in the film industry working with Dick Pope, first as a clapper loader on Life is Sweet, then as a focus puller on a series of films including Deadly Voyage and Secrets and Lies, and finally as a camera operator on films such as Me & Orson Welles, as well as The Outfit, right up to his final film, Hard Truths.

When I first worked with Dick in 1990, there weren’t many women working in camera crews. Dick took me seriously, and consistently offered me opportunities to climb the ladder, finally making it to camera operating, and becoming the first female member of the Association of Camera Operators.

He was a brilliant DP to work with – superbly funny, an irreverent wit that frequently had the crew bursting with laughter, our days on set were full of humour. But he was also extremely serious about his work. He gave total commitment to every film he worked on, always striving to improve each and every frame, right up to the moment of “turn over!”. Directors would know that he was giving them the best version of their vision, 1st ADs would sometimes grind their teeth as a flag was being adjusted at the very last moment. He wouldn’t compromise his craft.

His lighting was impeccable – even if presented with a bland, somewhat featureless set, his lighting would turn the scene into something full of artistry, creating the right mood to tell the story.

He loved to operate, and taught me so much over the years. He’d become ‘twitchy’ on films when he wasn’t operating (quite rare) because he wanted to have control of the frame, but was also a good collaborator, happy to receive comments or observations from camera crew, giving credit where due. He was generous with his encouragement and knowledge. I felt incredibly lucky to be working with him.

Dick had a small tattoo on his forearm that was a reminder of his documentary years. The tattoo had been done by an indigenous tribe (on a small island off Indonesia) who he’d been shooting a documentary about. A bond had developed between them all, and he was proud of the tattoo. He had an incredible energy for life. I remember talking one lunchtime while we worked on Topsy-Turvy and he declared he’d like to live forever! He seemed to come alive while shooting. On the set of Peterloo, he did a handheld shot practically running backwards with the cavalry advancing on him, having just turned 70 years old! One of many memories that make it so hard to accept that he’s gone.”

Lucy Bristow ACO Assoc BSC

“For 23 years, Dick Pope was the backbone of my professional career as a 1st AC. He was unswervingly loyal to his crew, and his unwillingness to ever hear anyone say no, always forced us all to find our inner strength, and step up our game. He was always teaching us, encouraging us, and supporting us on every project we did.

He was incredibly generous in his creative process, embracing any ideas we might have, and he always invited me to attend the grading sessions on the 12 films we did together, whether at the lab with a colour timer whilst viewing a film print, or latterly in the DI. He valued everyone’s opinion.

We would always watch film tests on the big screen, even booking the Odeon West End in Leicester square on projects with his long-time collaborator Mike Leigh. Dick knew how to do things properly.

There is one thing however that I will miss more than anything. His incredible sense of humour.

For those of us who had the fortune to work with Dick on a regular basis, we would spend so much time everyday laughing at his acerbic wit. Even remembering him with co collaborators on the phone after his passing, the conversations quickly went from tears of grief, to tears of genuine laughter. It felt cathartic to talk about him because he lifted our spirits so much on a regular basis.

It was an absolute privilege to know Dick, and this is how I will personally remember him: laser focused on the job, totally committed, uncompromising, generous, and funny as hell.”

Gordon Segrove, 1st AC

“The beginning of my long working relationship with Dick started in 1991 at Westway Studios in London as his key grip shooting a music video for Queen. I was delighted to get a call from Dick soon after to work on his next production and we went on to work on many films together.

It has been my good fortune to be able to spend so much of my working life alongside Dick, watching him practise his craft. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone as intensely invested in their work. With his lighting he was uncompromising, adding and tweaking things right up to the last minute, a perfectionist. Tense moments waiting for the sunlight to be just right, 1st ADs glancing at their watch, but he’d always be right and the results on the screen spoke for themselves. Once onboard a project I always noticed how his strong his collaboration with the director was, total commitment every time. He would always be keen for input from his crew but he had a great eye himself for developing a shot and making it into something out of the ordinary.

My memories will be of his sense of humour, all the laughs and those stories from his early days in documentaries and the rock and roll scene. It was a privilege, and it was fun.”

Colin Strachan, key grip

“I have been very fortunate to have worked with Dick Pope on seven films over the years. I had worked with a lot of Dick’s key crew on other productions with different DPs, and I had heard a lot of great stories about him, when I got the opportunity to team up with him I was thrilled.

My first movie with Dick was Me And Orson Welles in 2007. As soon as we started our prep Dick’s energy and enthusiasm were infectious, every subsequent production I experienced with him he always gave his all.

I look back at those seven projects with great fondness. We always had so much fun, a lot of laughter, and made some great looking films. Three of these productions were with Dick’s long-time partner in crime, Mike Leigh. These productions particularly stand out in my memory, it was a real honour to witness Mike and Dick working in such a unique way. I know that those experiences will never be repeated. A lot of my best days on a film set have been in the company of Dick Pope.

I will remember Dick as a wonderful professional, super talented, a true gentleman. He was incredibly loyal to his crew, and he respected and valued their contributions. He was a superb leader, his crews had huge respect for him.

When I was fortunate enough to have a pint with Dick and spend time away from set he would tell such terrific stories from his early career days, he was a great raconteur with a real sense of humour. Dick will be sorely missed by all of us who had the honour to be on set with him.”

Andy Long, gaffer

“I met Dick Pope many years ago when I was a film student at the Polish National Film School. At one of the first (or the first) Camerimage Festivals in 1993, Dick was showing the film Naked. I remembered we were mesmerised by this beautiful sensitive and raw film, so much that we unanimously chose this film to be awarded with our very own student award. I guess we were, as students from a very dogmatic and classic film education, hungry for soul, rawness, and humanity. This is very much how I remember the work of Dick Pope. Whatever genre or story he put his teeth in, throughout his career, there was always a very relatable and emphatic eye present. He never lost sight of the humane in his photography. Never photographing sets and scenes, but always a warm focus on the people and persons within his frames. His work has always and will remain an inspiration to me.”

Hoyte van Hoytema ASC NSC FSF

“I’m not sure what Dick disliked more – goodbyes or gushing tributes, so it’s perhaps a good thing that he isn’t reading this.

I first met Dick in 2008 on the set of Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, in which I had a tiny acting role. I remember Dick’s courteousness and humour like it was yesterday. It was also clear – from the very first day on set – that we were in the presence of humble, generous greatness.

In the decade that followed I watched Dick produce masterpiece after masterpiece with Mike Leigh and others, but our paths never crossed again. So when it came to finding a DP for Supernova there was really only one person in my mind.

Not for one second did I think he would even take the meeting, let alone say yes to the job. Truthfully, I still can’t believe he did.

Dick and I bonded immediately. From the moment we drove up to recce locations in the Lake District in his car – listening to music, talking about politics, photography, travel, film – and everything in between – we never really looked back. Ours was a truly meaningful – and therefore, I think, pretty rare – collaboration.

I vividly remember one day in early pre-production standing in a howling blizzard at the bottom of an absolutely enormous valley. When I suggested that the shot we needed was actually half way up the almost vertical, scree slope Dick turned to me with a cheeky glint in his eye, said, “You’re right you know,” and marched straight up there without a second’s hesitation. We all stood, mouths open, in awe of this 72-year-old man, leaving us all in his wake. But what a wake.

Dedicated, inspiring, loyal, always striving for perfection – that was Dick in a nutshell.

Making cinema is an odd, unique thing. It’s the meeting of heavy industry and fragile human emotion. Metal and glass colliding with the ephemeral magic of performance. Steel toe-capped boots dancing with ballet shoes – usually in a space miles too small and inadequate for the resulting fallout. At the epicentre of that, Dick was the mercurial conductor; the genius mediator. But as cinematographer and camera operator he was also our eyes. Some of the greatest performances in British cinema – in all cinema – have been captured through his lens. We have seen ourselves in these characters, cried at and laughed with them, been enchanted by their stories and laughed at this ridiculous world because Dick did first. We saw it all as he saw it, and he always knew where and when to look. How lucky we have been to have him. What a thrill.

Though Dick was as respectful and generous to the runner on their first ever day on set as he was to his life-long collaborators (of which he had many), he didn’t suffer fools. So I’m glad he suffered this one. I consider myself unfathomably lucky to have had the opportunity to create something with him – to have briefly shared a small corner of his remarkable cinematic universe.

But most of all, I will be forever proud that I had the privilege of being his friend. For all the hard graft on set, off it Dick was a raconteur, a wonderful companion and the single greatest person I have ever shared a bowl of prawn crackers with. To think I’ll never get to do that again makes me sad beyond words.

So long, my friend. I’m so sorry we never got to make that next one together. But thank you. For everything.”

Harry Macqueen, director (Supernova)

“The first time I met Dick, he told me I was wrong. We were on the phone, speaking amidst a terrible pandemic that seemed about to lift just enough to allow us to shoot this microscopic thriller. I went on at length, describing the visual approach I saw for the film, which was to be similarly micro: all tight close-ups and long lenses. And Dick listened to me politely for who knows how long, before finally saying, in his most patient tone, “Yes, yes. Alright. We should do the opposite of that.” He quoted an old Hollywood mogul: “We’re paying for the whole actor.”

In no conversation that I had with Dick in the years after did he fail to inform me that all of my cleverest ideas were rubbish. In no conversation did he fail to push against every one of my assumptions, every whim of my taste. No detail went unexamined, untested, uninterrogated. Dick simply cared too much about every frame that came out of his camera – a camera he held faithfully in his own hands – to ever settle.

Dick loved cinema. And he loved cinema people. And those of us who loved him did so for many reasons, not least of which was his unstoppable quest to make cinema better.”

Graham Moore, director (The Outfit)

“Working with Dick Pope in Malawi was an experience I will treasure for the rest of my life. He was not only one of the best cinematographers in the world but also an exceptionally supportive collaborator. I was inspired every day by his knowledge, determination and dedication. I feel so immensely privileged to have had the opportunity to work with him. A remarkable, irreplaceable artist.”

Chiwetel Ejiofor, director (The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind)

“I am so lucky, so honoured, to have worked with Dick Pope, and more than once. What a great guy, what an artist, and what a loss for cinema and all who knew and loved him. I remember heading into the making of a film in London (Me and Orson Welles, 2008) and thinking, “Is Mike Leigh in production? If no, I wonder if I could get Dick Pope to work on this?” Cut to us in prep, me talking to him about how I wanted to shoot a scene, etc. I can still see him, staring intently, taking it all in, spurting out a quick “yes” when he agreed or locked in to where I was going. Unblinking eyes, totally focused, absorbing everything. I felt like he had this great antenna, this all-seeing eye. And he was such a wonderful collaborator – seeing the possibilities and eager to explore, and always on behalf of the characters and the story we were trying to tell. He was never trying to impose a ‘signature’ style or himself so much, just trying to help the film actualize itself as it should be. And what a beautiful touch he had in lighting, what an eye, what a range, and for such a gifted artist, at the top of his profession, the least full-of-crap person imaginable… just a working guy, and so loyal to his crew.

While he’ll be remembered as part of one of the great director/cameraman duos (I think of him and Mike as a kind of working-class Bergman and Nykvist), he’d had this adventurous career before that, shooting all kinds of things, docs all over the world, and he had tons of funny stories and experiences. I’ll always remember him as a guy who was up for anything. “Let’s make this scene one long shot, starting in the hallway, entering the room, and following them around for the next four minutes.” “Yes!” “Wanna come work with me in Texas on a no-budget dark comedy, we have 22 days to shoot the whole thing?” “Yes!”

When we first worked together, digital was starting to be the rage and there was talk of shooting it in that format. Neither of us liked the look of that yet, and felt it really wouldn’t work for this period film we were doing, so film it was. A few years later on this next one (Bernie, 2011) however, that look had improved quite a bit, it was a contemporary story, we didn’t have any money, Dick had shot some tests he was happy with, and we were both up for taking the leap with the Alexa. Again, “Yes!”

I saw Dick not so long ago, when I was in London at the festival. We were talking about working together on a new thing, and he was feeling good about his latest with Mike. I just can’t believe he’s gone, that there won’t be any more films shot by Dick Pope. My heart goes out to his kids and wife Pat – what a sweet couple. And as I write this I’m somehow flashing back on Dick scouring the woods near my house for mushrooms (the ‘for cooking’ kind…). He knew a lot about them and was a mushroom enthusiast. He was a happy enthusiast about a lot of things, with a wonderful laugh and sense of humour, that so well complemented his critical edge. He will be so missed in this world but he leaves behind a lasting record, a kind of mountain of films, of what passed through his eyes and sensibility, and into which he put his heart and soul. They’ll all be there to experience forever, and every time we watch them Dick will still be communicating with us.”

Richard Linklater, director (Me and Orson Welles, Bernie)

“I have just come out of a screening of Hard Truths and felt compelled to write this tribute to Dick Pope. A man I never really knew well. I felt his vision stronger than ever in the darkness of the cinema today. Hard to comprehend he has left our physical world forever more.

In truth, I found we were always at odds with each other whatever we discussed and I found this consistently fascinating and entertaining on both occasions.

Camerimage is the obvious venue for the likes of us to cross paths. We would never be on the same set at the same time. So we met in Poland both times in the early hours of those cold November mornings after serving a long day on our own respective juries perhaps.

Whatever film we debated, we never really saw eye to eye. Aesthetics. Lighting. Narrative. We just disagreed respectfully and passionately. This just proves cinema makes space for us all, however different we are.

I have seen most of the list of films Dick made as cinematographer with Mike Leigh – all brave and non-compromising in their own special way.

I have left the cinema with laughing cramps and tears of pain. I never knew what to expect next.

Dick, this all stops now with your onward journey. I disagree with you really on this too! All things must pass.

Thank you for your impressive legacy which remains with us forever.”

Anthony Dod Mantle ASC BSC DFF