MULTICAM MASTERCLASS

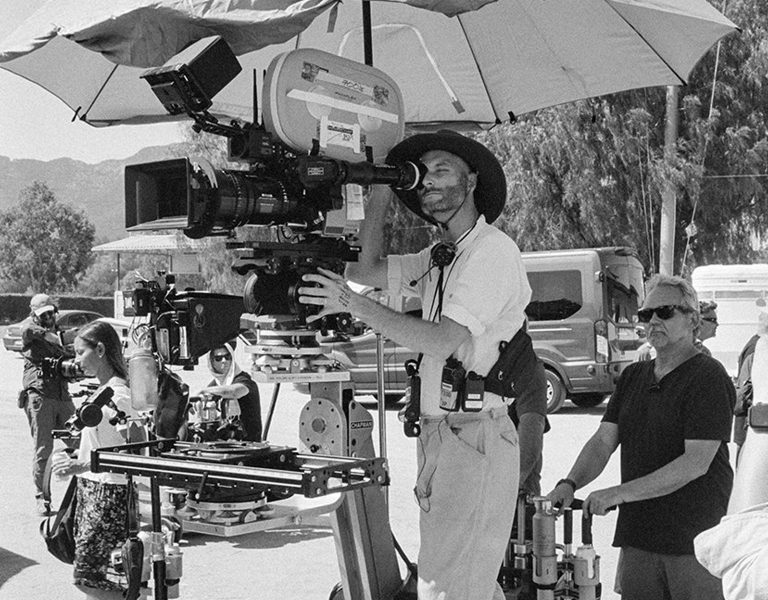

Todd Banhazl ASC was enlisted from the get go of Winning Time‘s production to ensure the HBO show captured the explosive rise of one of sport’s most iconic dynasties.

With Jerry Buss’ 1979 purchase of the Los Angeles Lakers, and subsequent drafting of Magic Johnson, the basketball team took America by storm and to this is day is widely credited as saving the NBA. The team’s fierce rivalry with the Boston Celtics was a major turning point for the league and is explored in great detail in season two of Winning Time.

The show has a distinct kaleidoscopic style which captures the fervour of 1980s Los Angeles and the explosive sinews of the basketball team on and off the court. Cameras from the time period are used to ensure an authenticity to Winning Time‘s aesthetic, but how they are used is often played with to ensure a wholly unique style. Whether that means fourth wall breaks, or using cameras for filming live sport to capture some of the show’s most emotional off-court scenes, the visual vocabulary of the show is truly magic.

British Cinematographer caught up with Banhazl to delve deep in to how this idiosyncratic style was achieved so flawlessly.

When was it decided that all the cameras used would be period accurate to the late 70s and early 80s?

That came from the very first conversation I had with Adam McKay when we were talking about potentially shooting the pilot together. I think we immediately, but separately, had had the same thought. Not only does the show need a kaleidoscopic collage and mixed format feeling, but it could be really cool to use the actual formats.

It started because of the basketball and we were talking about how to shoot the basketball scenes, and then the idea of using the actual cameras back then came to be. I did all this research and realised it was the Ikegami 2 cameras. During the testing phase we realised how incredibly emotional the cameras could look if you stopped using them like television cameras, and started zooming in to these really tight close ups. There was this really stripped down emotional look.

How did you go about deciding what cameras would be used to punctuate each scene with emotion? Or was that a decision for the editing room?

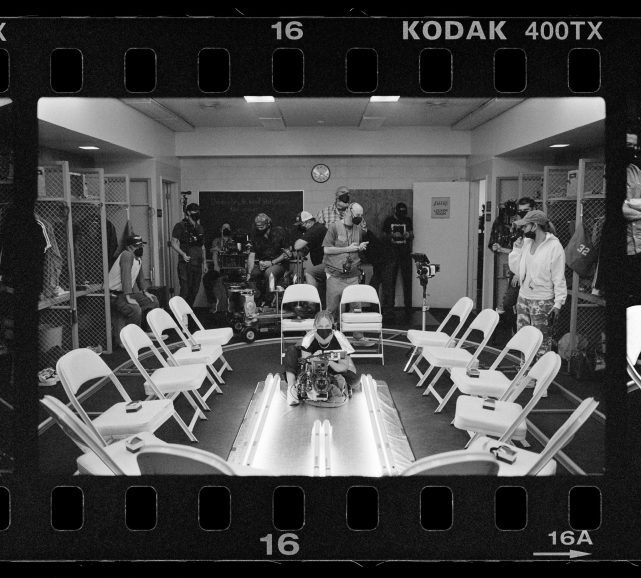

Yeah it was a mix, it’s always a mix. We had our creative rulebook and we knew what the formats could do, but we also wanted to allow the editors to be able to work with different paint brushes and allow them to have these accents when they needed them. Our basic workflow was A and B camera to shoot the beats we knew we needed no matter what, and then C camera was a mix of all the different formats: the 16mm camera, 8mm, the Ikegami 2, and in season 2 the VHS-C cameras.

It was always a conversation between me and my C camera operator Justin Cameron about what to do. We’d have conversations like: “For this scene, why don’t we get Pat Riley’s side axis close up on the VHS-C” or “Are we pretending this is archival? Are we saying this really happened?”. Similarly with using black and white, once in a while me and my director Salli Richardson-Whitfield would know which shot wants to be in B&W, but usually it was just from being on set and watching and deciding which shots worked best in monochrome. It was just about feeling those moments out.

All of the footage is original to the series, but you’ve shot it to look as authentically archival as possible to suit the storytelling. What was the reasoning behind this?

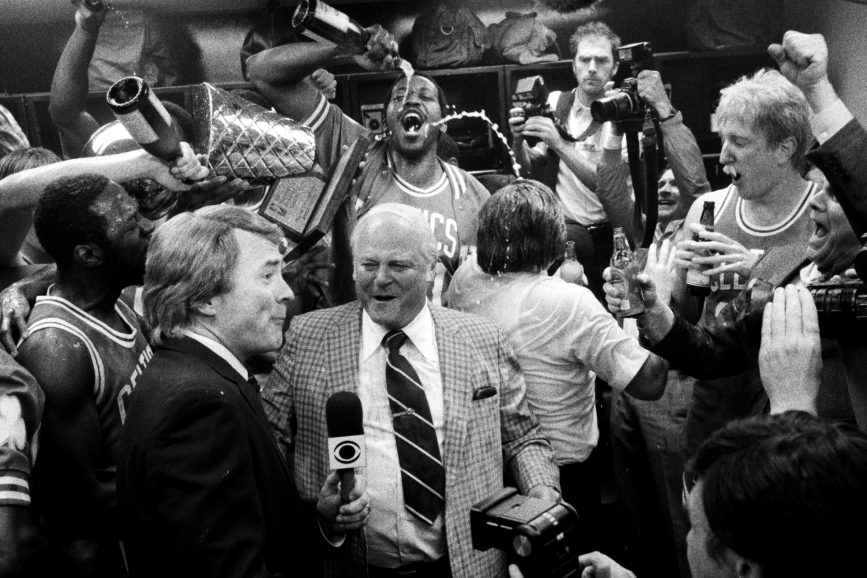

Yeah the goal was, that if we did our job right, the audience should have no idea what was real or not. We originally thought there was going to be a lot of archival, but for a lot of legal reasons, there ended up being no archival. So we ended up reproducing all of it. Ultimately, you shouldn’t be able to tell what’s archival or not, even though we’ve recreated all of it.

We’re also playing with these mythic characters from our culture and it’s the idea of them operating as larger-than-life myths whilst also having moments of them being stripped-down human beings. In every scene you’re able to see them as they want to be seen on 35mm as the big shots, and then also in this much rawer way in which they might not want you to see. The audience is constantly confronted with those two ideas.

It can up the stakes and intensity too. You’re watching these story beats happen, but seeing it on 8mm or a VHS cam hopefully gives the audience an idea that these was being watched by all of America, live. The format and aesthetic adds to the tension of so many scenes.

How did you balance the kaleidoscopic/fast-paced atmosphere without the format changes and style becoming a distraction to the story?

The way we shot it came from us testing and realising the cuts could feel good, but the editing style came from the pilot and from Hank Corwin. Hank is a genius who has worked on Oliver Stone movies and is a king of the mixed format and jutting cutting style. Audiences are just really smart and once you teach an audience what your visual vocabulary is, they can accept it as long as you are telling the story properly.

Was it stimulating creatively for you personally using vintage and mixed format cameras?

Oh my god, it’s been the best, most creative shooting experience I’ve ever had! It feels like, between the crew and myself, playing jazz. We have all the notes, the scales, and the instruments, but how we play them is a much more live, intuitive experience.

It’s really cool getting everyone on that page, especially the operators. We’d shoot most scenes with three cameras, six or seven for the basketball scenes. But you’d end up creating filming situations so you could capture lightning in a bottle and convey that feeling of luck to an audience, as you would in a real sporting situation. The 16mm and the 8mm camera were so tiny that were was no video feed on them intentionally. We could’ve done it, but we made sure we didn’t so the operator could just really get in there. They could get these really hidden, specific emotional beats from the characters without having anything in the way.

Were there many problems with the vintage gear?

Yeah, they break all the time!

They’re fifty year old cameras depending and it took a lot of upkeep. The team really took care of the cameras, covering them from bright lights between takes, we were constantly black balancing them. The morning of the shoot they’d sometimes go off wonky, so we had backups of backups, it took a lot of tender loving care.

Was there a favourite camera of yours to play around with?

I would grab the 8mm sometimes, but really my favourite were the VHS-C cameras in season 2. As we entered the 80s we started phasing out the 8mm. For me holding that camera you just immediately believe you are in a real scenario and it brought me back to my early days making videos with my parents’ camcorder. Everything is auto and there’s a little zoom control on the top and terrible hand shake because it’s so small. Just being in a scene with that, everything came alive.

How did you go about achieving the misty lighting effects that hyper-accentuate the 70s/80s feel?

The trick was that we would build all the lighting in to the sets to make it feel like these were real life locations that we had just shot docu-style. All the sets had ceilings built in to them and in the ceilings we either had practicals built in or fluorescent housings and in those we’d use RGB pixel tape to make it look like uncorrected fluorescents.

That way you could bring our films stocks in there – we created an Ektachrome reversal print look for the film – and you could shoot the sets as if you’d just turned up with a film camera Cassavettes-style with no lights. That’s the cocktail, and that’s how you can shoot it 360 and have multiple cameras shooting multiple formats.

Were you a basketball fan before the show?

I was not! Not until the show. My interest was always what these people meant for culture and their relationship with race and capitalism. In shooting the show, I’ve become a big basketball fan, I’ve fallen in love with the beauty and the balletic dance of it all.

Were the on-court scenes particularly difficult?

The basketball was definitely the hardest to shoot, it took us the longest while to figure it out. As the team gets better in the story, we got better at shooting it.

What was your set up like for the basketball scenes?

The basic breakdown was that we shoot the wide plays like they were real basketball scenes in our multiple television camera positions. We’d have multiple Ikegami 2 cameras up in the rafters, we’d have two in the centre, one in the centre back, some in the corners, we had two mounted behind the baskets, and we’d have one handheld on the ground. We’d have all these television camera operators and we’d shoot all the plays with our basketball doubles and all our height doubles and we’d watch it from our command station as if it was a live game.

After that we’d start moving in closer with the film cameras, starting with the wides on film cameras, multiple 35mm cameras on dollies or hidden in the crowd, a 16mm camera handheld shooting in the crowd, and then maybe an Ikegami 2 or 8mm camera shooting even closer.

Then we’d come in even closer for all the details, like stunt work for the plays and important emotional beats. We’d have a handheld on the court and then using speciality gear, like Steadicam, a crane or our basketball rollerblade operator, John Lyke. We’d pull everyone out of the arena so everything was 360 shootable and then bring all of our extras down to the lowest level of the stadium so the players were surrounded by the crowd. We’d do our oners with the rollerblade operator who basically had an ARRI 416 camera and a small backpack rig and no monitor, pulling on a wide lens. He always said he’d operate better without one!

What was the process like when using a rollerblading camera operator?

We’d rehearse John into the plays beforehand on multiple rehearsal days so that he was almost another player. We would do these switches where he would be on our cast member’s face going down the court and then he’d wrap around and in that moment we’d switch out our cast member with our height double and when we come around again, following a pass or whatever is motivating the movement, we’d be behind the double so you could see everything in wide. Suddenly he’d go for a shot and that would motivate another curve, which could then land back on our cast members face in a close up. All these switches gave the illusion that the game is actually happening.

Once you combine all those things, you feel emotionally connected to the players.

Did you shoot on a stage?

We shot season 2 at Warner Brothers in LA and we had 6-8 stages, but the main basketball stage was a 360 green screen set. We built the court and 15 rows of seating and we had also built two tunnel entrances with a tunnel that actually connected in the back. So you could go from the tunnel in the locker rooms and step out on the the court without cutting.

How much were you studying archival footage for accuracy, or was it just an aesthetic you wanted to replicate?

If the story beat revolved around something that really happened and it was definitely a key moment in history, then we studied the archival footage very closely, and tried to replicate it to the point of trying to match what extras were wearing or the blocking of the characters.

There’s a famous scene where Jerry Buss and Magic Johnson win and they’re holding the trophy and hugging and he’s crying, we replicated that exactly. We lit it exactly the same and the art department had painted the exact same line behind their heads. If something hadn’t really happened, or there wasn’t access to that moment, we would do our best to make it look like we were reproducing something using our tools.

There’s a scene where Kareem Abdul-Jabbar beats the scoring record, and of course there’s TV footage of this, so we replicated it to the point where the camera position moves over and zooms over to him and his parents. There’s a boom operator in the real footage and we matched that. We really tried to nail it so if you were to watch that and compare the two, you’d basically see the same footage, only our actor would be there which helps to blur the illusion. You’re dealing with actors who are playing extremely famous faces and you have to do everything you can to help people forget.

Do you have a new found respect for live sports camera operation?

Oh yeah, absolutely. I came up operating on live sports, events and documentaries. So I always had the respect for only having one chance to nail it, and of course we had more chances to nail it, but it was cool to treat the scenes like they were happening live. Our operators were so brilliant when treating these moments like it was a documentary and you just had to grab it. We’d run the plays live, the players would be acting, the fans would be cheering, the coaches would be lively, and we’d have multiple cameras rolling. They had to communicate with each other perfectly to have this doc style. I think that’s felt on screen and the way the cameras ping pong and pass off to each other. There’s a feeling that we were just lucky enough to grab it.

Another interesting element of the multi-camera set are the fourt wall breaks which help blur the line between reality and fiction even more. How were these moments decided and made to feel so spontaneous?

Most of the fourth wall breaks were in the script. We learnt early on that instead of setting a special shot for these, with the exclusion of monologues, we’d have little sides that characters would throw to the camera. We found the best way to do it was to have the character “steal” whatever camera was being used at the time. It looked better if they stole other people’s shots. We’d try it several times, with them turning to different camera positions, and we’d always find the best one. We wanted to give it that spontaneous feeling by delaying the camera adjusting to the actor in A cam, so there’s a feeling the cameras aren’t aware it’s about to happen.

With these breaks, the cast become very aware that this is the style and they get used to it. Later on, they’d improvise these amazing moments where it’s not planned and they’ll look over to the camera in the middle of an amazing performance and just not say anything, just a little glance. Some of those moments are so special and powerful. It only comes from everyone being in sync.

What’s a sequence you’re particularly proud of?

I’m very pleased with the basketball in the second half of the season, it gets really crazy. We really figured out how to outdo ourselves in the second half.

In episode 3, which I directed, we do some amazing work with Larry Bird that I really loved, it plays on this idea of his mythic background and backstory, whilst also humanising him.

It was my first experience directing something of this size and it was a really interesting exercise in letting go and trusting even more artists around me. As soon as I started directing I was so with the actor’s experience shooting on set I had no choice but to completely trust my DP Ricardo Diaz and totally rely on him. It felt amazing to stop thinking about the cinematography in that way.