Remarkable Creatures

Tim Cragg / Flying Monsters 3D

Remarkable Creatures

Tim Cragg / Flying Monsters 3D

Around two hundred million years ago there was an extraordinary development in the history of life on earth – an ancient group of reptiles made a giant, evolutionary leap into the skies. Known as pterosaurs, these flying monsters evolved into a multitude of forms, from amazing acrobats to marauding predators, and proved truly remarkable creatures that paved the way for every single species of bird on the planet today.

The story of their development has been traced in a new documentary, Flying Monsters 3D With Sir David Attenborough, which sees the renowned naturalist travel back in time to discover how and why these creatures took flight and why, after 150 million years of aerial domination, they vanished.

Initially transmitted on Christmas Day 2010 on Sky’s 3D channel, this £8 million Atlantic Productions’ documentary is to be released in IMAX Theatres and giant screens around the world in spring 2011. It was directed by Matt Dyas, with Anthony Geffen the producer, Pete Miller the editor, and Tim Cragg the cinematographer.

“You really are in with the gannets and flamingoes, but the 3D is subtle and immersive, like Avatar, rather than an in-your-face experience,” says Cragg. “People won’t be ducking and diving around in their seats.”

Cragg is a veteran documentarian, who has photographed over 80 primetime shows for the BBC including multiple episodes of Horizon, James May At The Edge of Space, and Richard Dawkin’s The Enemies of Reason. He won a BAFTA in 2007 for his photography on Simon Schama’s Power of Art: Van Gogh, and was BAFTA-nominated last year for How Earth Made Us. He spent 2009 lensing God In America, a $12 million drama for PBS in the USA.

He was approached by Atlantic Productions in early 2010 to photograph Flying Monsters 3D. “I was just as excited about the fact that David Attenborough was going to be presenting the film as I was about it being a 3D Imax feature. If he was attached to it, it was worth being attached to it,” he admits.

Speaking about the overall production design Cragg says, “The film was to have CG elements and CG creatures, and I very much wanted to have an input into conceptualising these, so that the final production felt true to one design concept. Fortunately Matt, the director, was open to collaboration and we set about storyboarding every single frame of the film, including all the CG elements,” he says.

Storyboards were drawn out by James O’Shea and, when these were agreed, were then passed over to VFX producer James Prosser at Zoom to create digital storyboards. The previs came along with details about lens choice, camera moves and basic lighting moods

“You can do so much with the CG camera, and it’s important that the CG animation team were aware of the limitations with the physical cameras, and to make sure the live action and CG matched up in post,” Cragg explains. “Also, David, who is 84, represents classical documentary, and it was his first 3D production. We wanted the film to be representative of him, so we adopted a classical, traditional approach to the framing of the live footage and CG material. We weren’t scared to hold on to shots.”

Cragg admits that this show was his first 3D experience too, and although he had no formal 3D training, he did scrutinise many 3D films, including Avatar, and shot test footage using glasses and a 3D monitor.

"I was just as excited about the fact that David Attenborough was going to be presenting the film as I was about it being a 3D Imax feature. If he was attached to it, it was worth being attached to it."

- Tim Cragg

He also says that IMAX was a major consideration in his approach to framing the production.

“IMAX films can run in cinemas for many years, and they have to have the big screen appeal. It’s hard to frame for IMAX and IMAX dome, as you need to have lots of headroom – the top of head is in the middle of frame. It took a week to get used to it, but it then became a natural process to frame-up, pop on the 3D glasses and visualise the result.”

By its very nature, shooting 3D has to have a larger team of people than a traditional 2D documentary. His crew included stereographer Chris Parks, son of the legendary and Academy Award-winning natural history cinematographer Peter Parks, Sarah Rollason as focus puller, stereography technician Simon de Glanville, Hugh Campbell as camera assistant, Kevin Zemrowsky the DIT, plus gaffer Gary Owen.

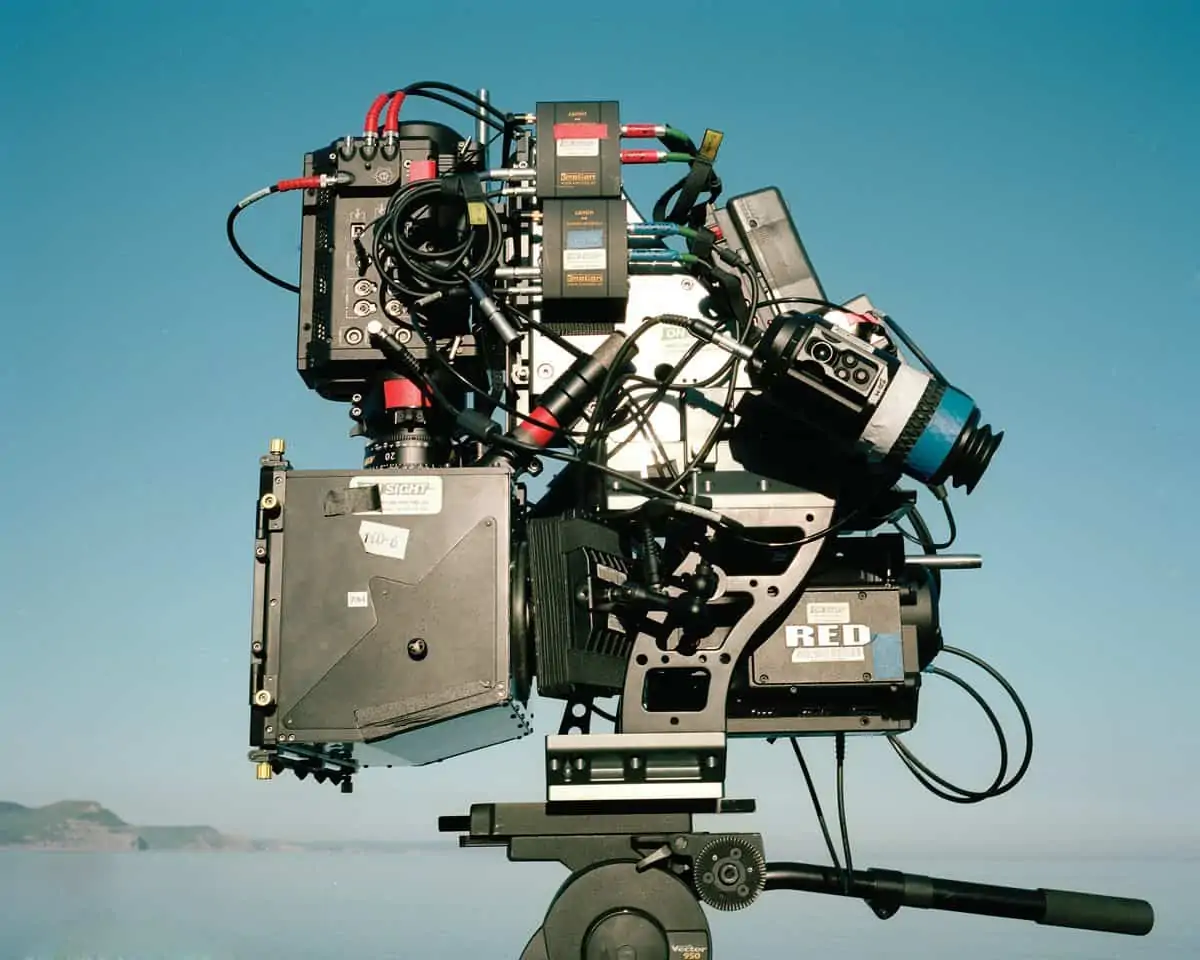

Shooting was done using an Element Technica Quasar Rig, with two Red One cameras shooting at 4K, a set of Zeiss Ultra Primes and Nikon macro lenses, supplied by On-Sight.

“The 3D rig had a huge presence, and weighed 56 kilos. Its size was appealing to me, as it was more akin to large format photography than photo journalism,” he says. “This again steered us firmly in the direction of traditional composition. Simply moving the camera was difficult. So I used a Canon 7D with prime lenses to find the frame. We would then discuss the level of 3D we wanted, and Chris Parks and the camera team would go about setting up the rig in position, and make the necessary alignments and adjustments. We tried where possible to have the camera on a dolly, or crane, but with so many exterior locations this sometimes was not practical.”

The production shot around the UK, France, Germany, various locations in the US, and at Bass Rock, a small island off Scotland, tallying 45 days across a 4-month period between March and June 2010.

“The biggest challenge for me was the composition, as the film was to be framed for various screens – 120ft IMAX, giant theatre screens, the IMAX dome, regular cinema screens, and Sky 3D television. So we decided to frame for the large screen, accepting that the smaller screens might have to have a pan and scan. Since we were shooting 4K we knew that the quality would still be outstanding on the pan and scan versions.”

Cragg says the 3D aspect was exciting to him as a cinematographer. “It felt pioneering, a refreshingly new approach to filming. Again, very similar to large format photography with massive amounts of depth-of-field, and wider lens choices than I would usually put on. Our lens changes and rig alignment generally took between 30 to 45 minutes, so we had to carefully plan how many lens changes we could achieve in a day.”

Of course, scrutinising footage as early as possible is a crucial element in 3D stereo production. Cragg says the team didn’t watch dailies in a formal sense, “but we did get continual feedback from Kevin our DIT who was on set the whole time, constantly checking for any differences between the left and right eye footage coming from the mirror rig – T-stop and focal differences, lens flares, and colour shifts. After each block of shooting, we’d would project and review the material in 3D at On Sight.”

Visual effects supervisor on the production was Robin Aristorenas. The off-line edit was complete at Atlantic, with the final on-line 3D conform, depth grading and stereo fixes done at On-Sight using SGO’s Mistika system, and the audio post done at Halo. CG elements were provided by Molinare in London, with Fido in Sweden providing CG creature work.

Cragg is now lensing three one-hour 3D films with David Attenborough for Sky 3D at Kew Gardens.