A sobering look at Trump’s shadow over Hollywood’s awards season, plus exclusive insights into the new films Saturday Night and the cinematography of The Fire Inside.

“One word came up again and again when I asked European officials about the stakes of the American election: existential. ‘The anxiety is massive,’ Victoria Nuland, who served until recently as under-secretary for political affairs at the state department, told me. Like other diplomats in the Biden administration, she has spent the three-plus years since Trump unwillingly left office working to restabilise America’s relationship with its allies. ‘Foreign counterparts would say it to me straight up… The first Trump election—maybe people didn’t understand who he was, or it was an accident. A second election of Trump? We’ll never trust you again.’”

And that excerpt, dear friends, from McKay Coppin’s article What Europe Fears, appearing this past summer in The Atlantic, and recounting a NATO gathering to game out the implications of multiple felon Donald Trump’s return to the White House, is perhaps one of the most succinct summaries of what this will mean going forward, for relations on either side of the proverbial pond.

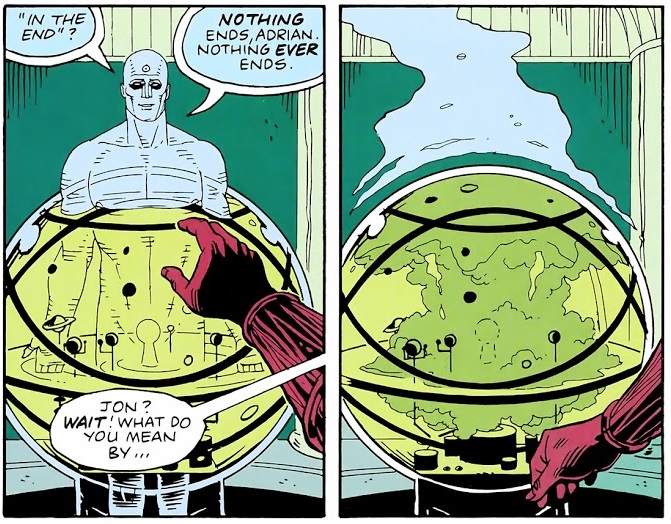

There will be much to write about – and likely, for citizens on either shore to do – in the months and years ahead, but right now it’s all feeling a bit like Dr. Manhattan’s admonition at the end of Watchmen, that “nothing ever ends”.

As for other things that recur, some hopefully less dystopian, it’s also time – ironically? – to shift into Award oeuvre mode with this column. But the election has fallout even there, like the sudden recontextualisation of various award season favourites (suddenly, Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig’s story about a family torn apart by an authoritarian government doesn’t seem like it’s only about a place “over there,” nor do Adrian Brody’s jeremiads in The Brutalist, about the feeling of being an unwelcome immigrant, seem consigned to the past, just as for instances from the last two screenings prior to this month’s deadline). This recontextualisation was also thoughtfully written about by Katey Rich in her Ankler column on 8 Ways The Election Changes the Oscar Race.

Two longer-term questions, involving the intersection of entertainment, TV, and sports, so far not addressed, involve the U.S. agreeing to be host to the World Cup in 2026 (along with Mexico and Canada) and the Olympics, here in Los Angeles, in 2028. Depending on what happens in the months and years ahead, one wonders how the rest of the world will be viewing the U.S. by then, especially if, say, the attempted deportation of millions of immigrants has been attempted by the incoming government.

Additionally, if you were a female athlete, and healthcare for women continues to be, for all intents and purposes, outlawed here, would you want to come to the U.S. for a few weeks? This question may be of import to film and TV workers too, both above and below the line, in deciding whether to accept a role or a crew position. And to Hollywood studios, in deciding where to shoot a given project (and who’s willing to work where).

Also, given the heavy tech bro influence on the Trumpian return to authority, it may be worth keeping an eye on what kind of tensions may arise in terms of the types of content that tech money will want to fund, and whether those holding the purse strings suddenly want a heavier hand in what content is released, or not – a la the publishers of the Los Angeles Times and Washington Post.

There will be much to write about – and likely, for citizens on either shore to do – in the months and years ahead, but right now it’s all feeling a bit like Dr. Manhattan’s admonition at the end of Watchmen, that “nothing ever ends.”

As for other things that recur, some hopefully less dystopian, it’s also time – ironically? – to shift into Award oeuvre mode with this column. But the election has fallout even there, like the sudden recontextualisation of various award season favourites (suddenly, Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig’s story about a family torn apart by an authoritarian government doesn’t seem like it’s only about a place “over there,” nor do Adrian Brody’s jeremiads in The Brutalist, about the feeling of being an unwelcome immigrant, seem consigned to the past, just as for instances from the last two screenings prior to this month’s deadline). This recontextualisation was also thoughtfully written about by Katey Rich in her Ankler column on 8 Ways The Election Changes the Oscar Race.

QUESTIONS AND NO ANSWERS

Two longer-term questions, involving the intersection of entertainment, TV and sports, so far not addressed, involve the US agreeing to be host to the World Cup in 2026 (along with Mexico and Canada) and the Olympics, here in Los Angeles, in 2028. Depending on what happens in the months and years ahead, one wonders how the rest of the world will be viewing the U.S. by then, especially if, say, the attempted deportation of millions of immigrants has been attempted by the incoming government.

Additionally, if you were a female athlete, and healthcare for women continues to be, for all intents and purposes, outlawed here, would you want to come to the US for a few weeks? This question may be of import to film and TV workers too, both above and below the line, in deciding whether to accept a role or a crew position. And to Hollywood studios, in deciding where to shoot a given project (and who’s willing to work where).

Also, given the heavy tech bro influence on the Trumpian return to authority, it may be worth keeping an eye on what kind of tensions may arise in terms of the types of content that tech money will want to fund, and whether those holding the purse strings suddenly want a heavier hand in what content is released, or not – a la the publishers of the Los Angeles Times and Washington Post.

2024

There’s a reason the most fearsome ghost in A Christmas Carol was the one from the future. So let’s, then, look at some of the work from the year wrapping up now, in what already feels like more innocent times.

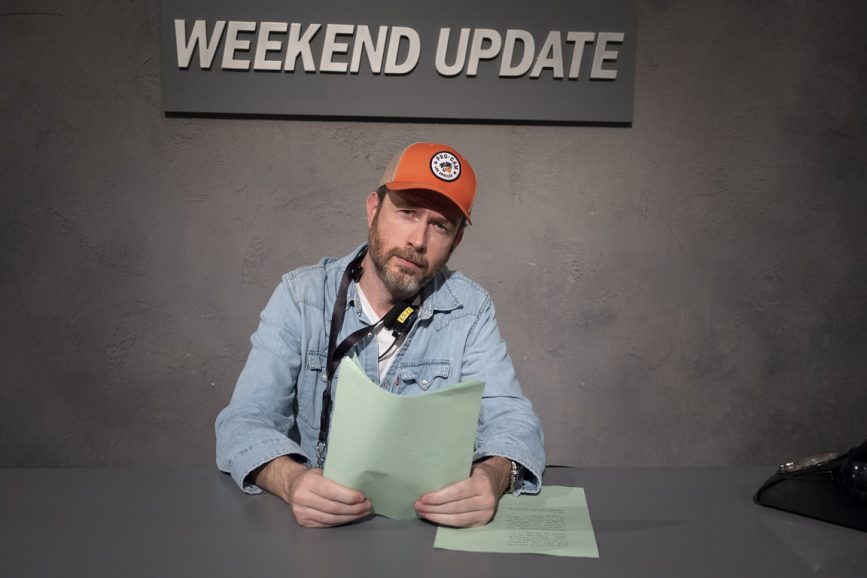

Which also describes a lot of the feeling that comes from watching Saturday Night, director Jason Reitman’s loving and frenetic recreation of the very first evening that Saturday Night went Live, in ‘75. Though this isn’t about what happens after the show starts, but rather, a film purporting to be about a “real time” 90 minutes prior to air.

The script from Reitman and Gil Kenan (a previous collaborator with Reitman in later Ghostbusters films – a franchise started by Reitman’s late director father Ivan, in collaboration, of course, with the original SNL alums who wrote and starred in it), compresses several weeks of events into that apocryphal time frame: There is Jim Henson wondering why the Muppets aren’t getting any script pages! There is John Belushi wondering if he should really sign that contract! There is Milton Berle exposing the also-apocryphal part of his anatomy! There is Garrett Morris talking to Billy Preston wondering if perhaps the show is going to be a little – or a lot – more white than it thinks it will! And there are the network heavies thinking they should instead go with a Johnny Carson rerun for that time slot, along with a threatening call to a young Lorne Michaels, from Carson himself, countering his nice-guy image! Et al!

Eric Steelberg ASC was another of the director’s previous collaborators, going back not just to stories about ectoplasmic overreach, but earlier still, “since we were teenagers,” as he recounts. “We cut our teeth” on short film collaborations, then did early features separately, joining later for the director’s 2007 breakthrough Juno. That was followed by Young Adult, “one of the first feature films shot on the Alexa,” which came about when the New York rental house they were prepping at asked “hey, you want to see this new digital camera we got?”

“It was so new,” Steelberg continues, “the media didn’t work. You had to record it in a separate box.”

All these years and projects later, you might think that was a digital turning point, and in some ways it was – newer Alexas would be used for newer Ghostbusters films – but not for Saturday Night. Which wasn’t merely shot on film, but 16mm film, to boot.

“We longed for the look,” Steelberg says, recalling early conversations about the project, pre-pandemic. Later, they returned to the idea, but it “wasn’t as easy as I’m making it sound,” as he refers to “whole studio conversations” about that choice. But director and DP wanted it since it was a “story that took place when TV was changing (and) we wanted to tell (it) analog.” Additionally, Steelberg adds “16mm now looks like 35mm did in the 70s – in colour palette and softness, (and) the size of the camera was smaller than 35,” a consideration given how busy the camera would be following characters around those recreated NBC studios.

The camera in question was an ARRI 416, using, variously, ARRI Master Primes, Zeiss Ultra 16 Primes “a couple of Zooms,” and a Fujinon Premiere 18-85.

“We used the zooms as variable prime lenses – even reframing during pans. We wanted the camera to be another actor in the scene – to get that close and intimate.” That ARRI roams down hallways, in and out of dressing rooms, up staircases, round skating rinks (this is Rockefeller Center, after all), and generally keeps up the propulsive energy, while also – especially for those of us who were around then – filtering it through its own sweet haze of memory (and perhaps, given who of the depicted characters aren’t around anymore, and what’s become of the world’s potential since, a pronounced sense of loss, as well).

“Also for me,” he adds, using 16mm helped add “a softness, there was a lack of resolution – a natural kind of diffusion. It created a separation (and) a point of view narratively speaking,” while “the constant movement of the grain felt like the blood pumping through everyone’s veins,” along with the adrenaline that came when the execs finally decide not to go with Carson, and instead, for the first time, in what would become 50 years and counting, to go “Live! From New York!”

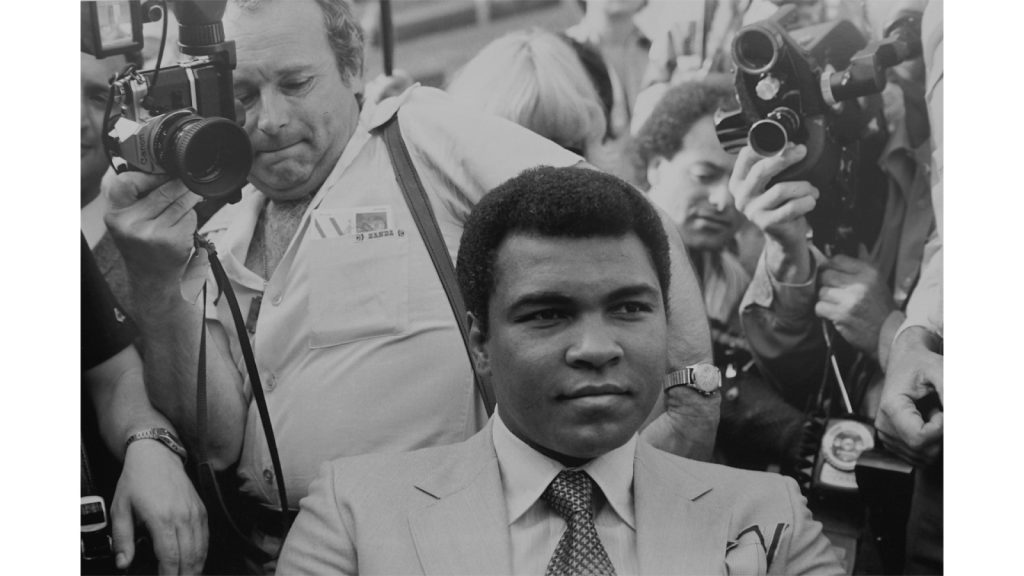

And on the topic of pumped-up adrenaline, another unexpected theme of this column is the boxing film, which adds an additional meaning to the idea of certain movies, or their crafts, being “contenders.”

In this case, we have MGM’s The Fire Inside, and the indie release The Day of the Fight. The first is about the too-little-known story of Flint, Michigan’s Claressa “T-Rex” Shields, who, in 2012, became the first American female boxer to win an Olympic gold medal. And in the manner of women usually having to work twice as hard as men to obtain the same general acclaim or respect, she had to do it twice, repeating again in 2016, before things like “endorsements,” and other payoffs for years of hard work, started to come her way.

Her story also marks the feature film debut of the renowned Rachel Morrison, ASC, who became the first woman nominated for an Academy Award for cinematography, for her work on Mudbound (the same year she also shot Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther).

She has since moved successfully to the director’s chair, with TV credits that include instalments of The Mandalorian and American Crime Story.

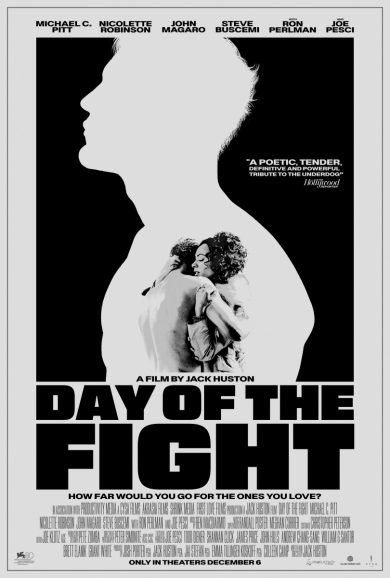

The Day of the Fight, written and directed by Boardwalk Empire-alum Jack Huston (yes, of that showbiz Huston clan), follows now-disgraced boxer Mike Flannigan (played by fellow Boardwalk alum Michael Pitt) as he wanders the streets of Brooklyn and lower Manhattan on the day of a possible comeback fight, visiting people from his rubble-strewn life and trying to set some past mistakes right, before it might be too late.

It’s a compelling, compressed-time narrative, and almost doesn’t even need its concluding, Madison Square Garden bout to hold your attention. It was also shot in black-and-white, and, being set in the 80s, recalls character-driven films made in that decade (or the one before it).

Conversely, The Fire Inside’s Flint scenes – at least the exteriors – were all shot there. “That was a hill I was willing to die on,” Morrison says, and it pays off in adding its own authenticity to the proceedings.

The bulk of the production then moved to Toronto, where there were additional locations and stages – and lighting choices for every fight, whether an Olympic bout or one of the underground ones Shields needed to do later, to help make post-Medal ends meet. As for Flint, it was “very low-fi,” according to cinematographer Rina Yang. “We didn’t want to go too fancy – we wanted it to be period-accurate to the era.”

So what was it like for Yang – who’d previously shot several Taylor Swift videos, an Euphoria episode, and the underrated Amazon Prime movie Nanny, among other things – to have such a renowned DP like Morrison as a director and collaborator?

“We speak the same language,” Yang says, a shared linguistics that included also sharing LUTs as they were created, and as Morrison notes, “a shorthand – I know what that is,” giving an example of the sun going down, and needing to match a shot.

Morrison would also operate some of the time, allowing her to whisper additional directions from behind the camera, getting “the benefit of (Rina’s) eye being on the technical,” and leaving her free to concentrate on performances.

Simonite also notes the value of collaboration, not only with Huston, who, along with what he describes as his “magnetic energy,” also has a Clint Eastwood-like knack for keeping things to one or two takes, but also his gaffer Callum Shaw, who was “quite young and very talented (and) very familiar with all the nuances, LEDs, iPads – he has a nimble crew.”

Many of those challenges came in the location doubling for Madison Square Garden, and “having lighting being the right place – especially when you don’t know where you’re going,” as Huston “had in mind to do a lot of oners (and) wanted to work in a fluid way,” without marks, letting the actors find their performances. Something even trickier in a culminating boxing match.

There were also the more “seasoned” members of his crew who were able to complement Callum’s innovations, like hiding lights to allow those spontaneous camera moves. Simonite mentions his own operator, the highly-regarded Jim McConkey, had “worked on Ali, and had some thoughts about using wider lenses and being closer to the action.”

But given that the film is also shot in black & white, that brings up certain other, inevitable comparisons: “If it’s black and white,” Simonite says, “it will be compared to Raging Bull. And that’s a high bar.” But they didn’t even look at that film while prepping, instead viewing things like B&W 50s-era classic On the Waterfront, and another gritty tale directed by Huston’s grandfather, John: The too-neglected 70s-era Fat City, with Stacy Keach toughing it out in the delta-side city of Stockton, in California’s Central Valley.

The B&W was “also a practical choice. In colour, when you’re shooting different parts of New Jersey for Brooklyn, maybe there’s a bright blue recycling can. In black & white, you can get away with a lot more. It was also a bit of a parable in a way. It’s a little bit (of the story and characters) trapped in a timelessness.”

They shot on an Alexa 35, capturing “all the chroma information – the colour information gave us somewhere to go,” along with Leica Summilux glass, which “jumped out as timeless and classic” after running several tests with them, and “also as a practical choice – (they were) very compact.”

The need to be able to keep the camera moving also informed Morrison and Yang’s choice of switching to a Sony Venice (after the project was revived, post-pandemic), with modified Panavision Panaspeed lenses. The sensor, however, was from a Venice I, and was put back into a Venice II Rialto, which Yang thought would be “beneficial – to have the small body.”

Yang and Morrison also talk about things like halation and gamma curves, in their choice of gear – the bleeding of an image into its dark areas, the intensifying brightness and contrast of an image – but Morrison also says “we weren’t trying to be crazy stylised. It’s so important that it felt authentic… that (audiences) believed it.”

Anchored by riveting performances from Ryan Destiny as Shields and the always watchable Bryan Tyree Henry as her trainer and mentor Jason, working off a script by writer/producer Barry Jenkins, everything combines to achieve Morrison’s aim that “at the end of the day you want the audience to feel like they’ve lived in her shoes.”

Those shoes may be lace-up Everlast footgear, but the aim is achieved, under the tutelage of a director Yang calls “the maestro of the orchestra,” with both director and DP talking about the “lovely collaboration” among all the departments.

“We looked forward to coming to set,” Yang says.

If only the future on this side of the pond felt that way now. DP Peter Simonite reports, though, that if you’re trying to shoot period Brooklyn, in the current, gentrifying version of that borough “there’s a lot to avoid” – beyond just the numerous Starbucks that have popped up. Consequently, they wound up shooting in New Jersey, where “several cities still have a look that you can sell as ‘period Brooklyn.’ It was a really incredible journey because of the kind of filmmaker Jack is – I think that shows up on the screen.”

If only the future on this side of the pond felt that way now.

Regardless, we’ll be reporting from a little farther into it a month hence. Take very good care ‘til then. AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com / @TricksterInk