TURNING THE PAGE

Bridget Jones gets a cinematic refresh with masterful cinematography, blending natural lighting, vintage lenses and grounded visuals for a glowing new chapter.

How do you refresh a long-running franchise like Bridget Jones? Well, it helps when you bring in filmmakers who are brand new to the series and brimming with ideas. Irish cinematographer Suzie Lavelle BSC ISC has made her name shooting acclaimed television shows like Severance, His Dark Materials and the Lenny Abrahamson-led adaptations of Sally Rooney’s novels Normal People and Conversations with Friends, projects that are all a world away from the bright and poppy environments that Bridget occupies.

When Lavelle was contacted about this latest take on Helen Fielding’s beloved singleton, she was heartened to learn that Michael Morris had signed on as director. “I’d seen Michael’s film To Leslie and I loved that film so much,” she says, admitting she was intrigued to know how Morris would tackle a fourth entry into the Bridget Jones universe. As it turns out, Morris was a fan of Conversations with Friends, especially the way Lavelle approached the show’s visual language. “It was shot on film, quite naturalistically, very handheld,” explains Lavelle.

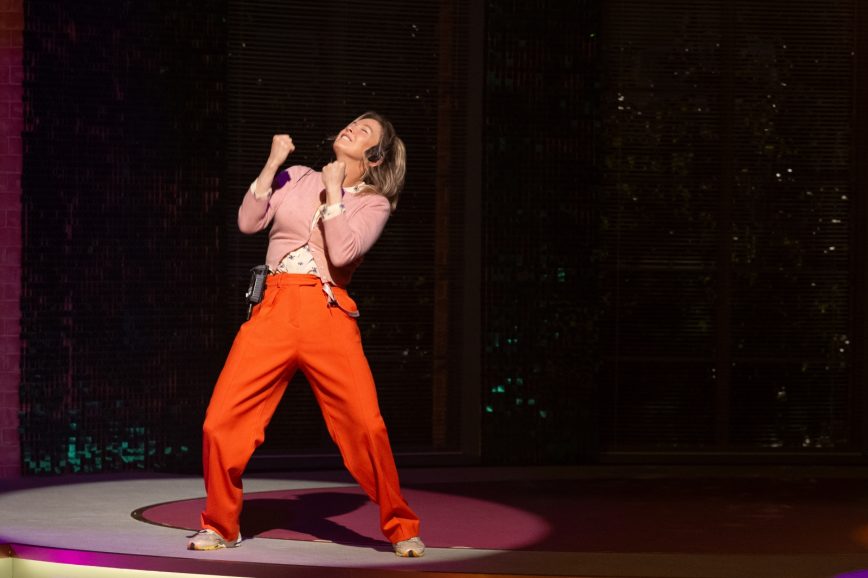

The mandate for Bridget Jones: Mad About The Boy was established swiftly. Or as Lavelle puts it: “Just try and make it a little more grounded.” Although there were brief conversations about shooting on celluloid, echoing the original Bridget Jones’ Diary (2001) and follow-up Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004), it was ultimately decided that filming on digital was more practical and in line with the third film of the series, Bridget Jones’ Baby (2016). The camera chosen to capture the new adventures of Bridget, once again played by actress Renée Zellweger, was the ARRI Alexa 35.

While Lavelle was familiar with the Alexa LF, this was her first time working with the 35, although she found it perfectly suited her needs. “The overriding thing in terms of the photography of this project is about true skin tones,” says Lavelle. “I really wanted honest skin tones in the film and that’s something that’s quite hard to get digitally. That’s the benefit of shooting film when you can. So, the Alexa 35…it’s the closest camera to film in terms of replicating skin tone.”

With production company Working Title keen on a two-camera set-up, to help capture the comedy beats from the talented cast, Lavelle operated A camera and Simon Finney ACO Assoc. BSC commanding B camera (Steadicam operator Jake Whitehouse ACO also helped out in the final two weeks on the shoot, notably for a scene near the beginning, when Bridget’s friends appear in her kitchen as figments of her imagination, requiring a dextrous one-take shot). Meanwhile, in keeping with the organic and naturalistic feel the team wanted, Lavelle deployed vintage Canon K35 lenses, a package she was very familiar with.

“I used those lenses on Normal People. K35s. They’re beautiful,” she says. “They’re quite soft, really fast lenses, so you could push them for a very narrow depth of field and they’re very kind to skin tone. Flare beautifully…which I love. It means for me when I’m operating handheld, I can control the amount of fill, the lens is directing towards the source in the window. And that’s really helpful for something where you don’t want to put a lot of lights inside the set. I quite like the set to feel like the set, with not a lot of equipment in there, unless I have to and try to light from the outside.”

Team work

Collaborating with Lavelle was gaffer James Bridger, who first worked with her on the 2023 film The End We Start From. Lighting this fourth Bridget Jones instalment was all about treading a fine line. “Bridget has to have an aura and a glow,” he says. “So, it can’t be really stripped back.” Nevertheless, Lavelle was keen for the scenes not to be over-lit. “It just doesn’t want to feel like it’s been manipulated too much,” Bridger adds. While they weren’t going to be shooting on film, that didn’t mean other traditional equipment could not be embraced.

“Suzie is very, very classical in her approach. She loves to shoot on film and to complement that, she loves to use tungsten lighting. And you can’t beat that,” says Bridger. Adds Lavelle: “I don’t really use HMI or LED a lot and that’s all part of [finding] the kindest lights to skin tone and the ones I feel represent daylight the most accurately in terms of aberration and nuance.” Still, with the script requiring the production to visit forty-plus London locations, using tungsten lighting was no mean feat. “It’s just challenging with the modern-day approach of speed and reducing footprint,” adds Bridger. “They’re such big units.”

The gaffer deployed an array of lighting equipment, both for the multiple exteriors and the interior scenes of Bridget’s house, all shot at Sky Studios in Elstree. “Our main arsenal of lights…to penetrate, we’d use 20K Fresnels. Then for the softer ambient push, Suzie loves a quarter Wendy for a diffusion. And then sometimes we’d also use Dinos as well, 12K Dino lights. And then, if we were struggling for space, sometimes we’d use these 2K Bathtubs.” With four of those on hand, the production also used 2K Spring Balls and Jem Balls as well as Wagon Trains, covered lighting rigs that are “amazing on the skin”, says Bridger.

Getting intimate

With the film shot across the summer of 2023, Lavelle notes that her “biggest challenge” was that the script contained a number of key exterior scenes at night, from the moment Bridget arrives at a friends’ house alongside the ‘ghost’ of late husband Mark Darcy (Colin Firth) to her first kiss with new younger boyfriend Roxter (Leo Woodall). With night not falling until late evening and many of these scenes taking place in residential areas across London where there were restrictions on filming, timing was everything. “It was all about pre-planning and execution and crossing your fingers and going, ‘God, I hope we get it!’ And we did, thank God! It’s literally the generators are going off at 11…you’re out! There’s no wiggle room!”

The story also spans from summer to winter, with a couple of scenes in the final act requiring the streets to be covered in snow. In particular, a shot with Bridget and her daughter walking along a real Hampstead street, with shops all decorated for Christmas. “We basically shot it in the height of summer,” informs Bridger, who notes that fake snow was used to create a winter wonderland feel. Again, lighting was key. “We were trying to make it feel sourced from the streetlights,” explains Lavelle. “And the art department were great…in that we just carried some streetlights around with us!”

With director Michael Morris also inspired by another Working Title production, the 2013 Richard Curtis tale About Time, the intention was to echo that and shoot as much handheld as possible, adds Lavelle. “We probably only did about thirty percent handheld for the first couple of weeks and then realised this is a hundred percent the way to go. And did a lot of it handheld after that.” A 50-foot Technocrane was used to capture a couple of magical moments – Bridget first meeting Roxter when she’s stuck up a tree on Hampstead Heath and his later appearance at a birthday party. “But the majority of everything else was handheld. And that was certainly our process in her house.”

With so many scenes filmed inside Bridget’s home – in the kitchen, living area, bathroom and upstairs bedrooms – Lavelle worked carefully with production designer Kave Quinn, who crucially added a slanted, recessed window in the doors in the middle portion of the set to allow for extra illumination. “We used Wendys to light that set,” says Lavelle. “And you wouldn’t traditionally use those in a studio, but for us, it was really helpful that we could do.” Two or three Wendys were fixed to a moveable ladder beam, with a silk diffuser also used.

“So, when the scene was predominantly in the middle of the set and I didn’t see the window, I could drop everything and push much more light in.”

Skin deep

The other major interior was the TV studio where Bridget returns to work, on the morning show ‘Better Women’. The production was able to access Television Centre in White City, using the same space that The Graham Norton Show films in. “I had never lit a studio of that scale before,” remarks Bridger. “We basically stripped it all back and did it from scratch, which we thought was going to be a tough job. But they [the Television Centre lighting team] do that on a regular basis…because they switch between the shows so quickly.”

Lavelle admits it was a daunting sequence to shoot, especially when Bridget arrives there for the first time and finds the studio a hive of activity, all captured in a stunning 360 degree shot. With the production’s lighting crew and the Television Centre’s lighting crew to manage, “keeping communication fast and managing the skin tones and knowing which were our lights and their lights [was tough],” she says. “Just understanding how shadows were going to read. And having the lights not in shot…but angling correctly so it’s still flattering…it was challenging in there, for sure.”

Seeking out consistency was something Lavelle carried on into postproduction and the grading. The cinematographer worked, for the first time, with Toby Tomkins at Harbor. “It was my first time working with Toby and I’ll definitely do it again. He was really great for the project. I talked to him a lot about a film emulation feeling and he really helped me with that.” Again, it was about “being true to colour and skin tone” for Zellweger and her high-profile co-stars, says Lavelle. “That thing of not feeling the lighting too much and photographing them like their beautiful selves!” With Bridget now in her forties, she would no doubt approve.