Enemies Unite

Steven Poster ASC / Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore

Enemies Unite

Steven Poster ASC / Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore

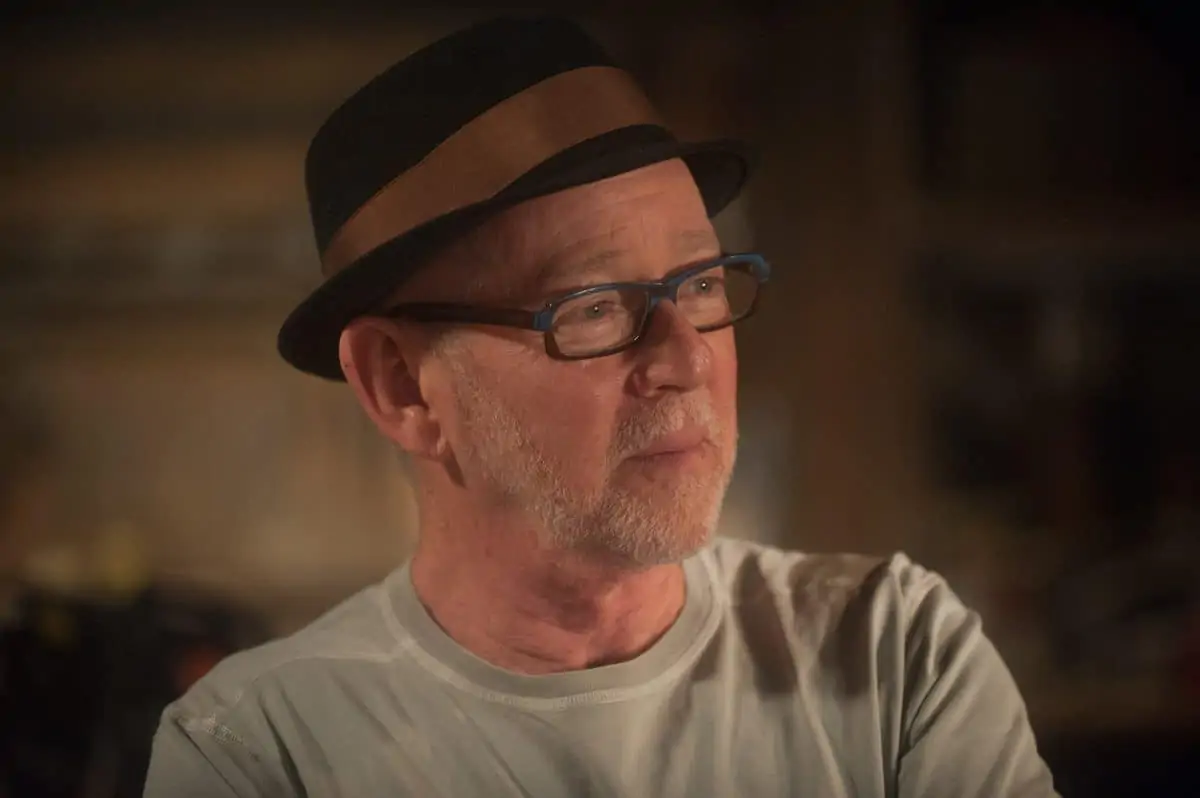

You don’t need all of the fingers on one of your hands to count the number of cinematographers who have shot films with dogs and cats in all leading roles. Steven Poster ASC joined that exclusive club when he shot Cats & Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore, which Warner Bros. released to cinemas in 3D format this summer.

The film is a fantasy drama with real cats and dogs cast in the leading roles. The animals interact with human characters portrayed by Chris O’Donnell, Jack McBrayer, Fred Armisen and Kiernan Shipka. The story: Kitty Galore, a former spy in the timeless battle between dogs and cats, has a diabolic plan to take over the world. Members of the two species who are age-old enemies unite to save themselves and their humans from the threat she poses.

Poster, current president of the International Cinematographers Guild, brought a diverse range of experience to the project. He has shot films with animals in prominent roles before, e.g., Stuart Little 2 and Big Top Pee-wee, and knew that it would distract them if cameras and/or people got too close. He also knew that it is a serious understatement to say lighting hairy animals is challenging.

He describes Cats and Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore as, “An intriguing James Bond-type story. After about 30 seconds, you believe the dogs and cats are smart and funny and that they really know how to talk.”

The film was produced on stages and at practical locations, including a large amusement park, in North Vancouver, British Columbia. It was his first collaboration with director Brad Peyton. “Brad had a sense of how to put the story together in a graphic way that made it an intriguing experience for me,” Poster says. “I think the fact that he has directed animated films has a lot to do with the emotional quality that he brought to the way the story unfolds.”

There were also close collaborations with visual effects supervisors Jerome Chen and Richard Hoover from Imageworks and Blair Clark from Tippett Studio. Poster had established relationships with both, having worked with Chen on Stuart Little 2 and with Hoover on commercials.

Chen, Hoover and Clark supervised the creation of computer-generated animation which replaced the faces of dogs and cats whenever they were talking, added CG characters and created entire scenes.

He explains that a decision was made to produce Cats and Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore in traditional 2D format on 35 mm film in 1.85:1 aspect ratio, because shooting with a large 3D rig would have distracted the animals and made it difficult to get shots they needed to tell the story. The 2D images were converted to 3D during post-production.

Poster covered scenes with two Panaflex XL cameras mounted with Primo lenses. One of the cameras was on a 20-foot Technocrane most of the time.

“That allowed us to get incredible close-ups without startling the dogs and cats,” Poster says. “The trainer, Boone Narr, and his crew were the only ones who came close to the animals. He and I had collaborated on Stuart Little 2. He doesn’t teach animals to do tricks. He teaches them how to learn. If you’re lucky you can get two or three animals together at the same time. But, many times we filmed them separately when we could shoot split frames and clean plates.”

Poster stresses that lighting dogs and cats had unique challenges, because their fur “eats light.” He cites a scene where the characters were a German Shepherd with a black snout and an Anatolian Shepherd. Poster describes the latter as, “a very large white dog with a black face. That’s about the worst combination you can imagine.”

A beautiful German Shepherd, whose movie name is Diggs, plays a prominent role in the film. Poster explains that not only are the dog’s eyes on different sides of his face. They are deep-set and surrounded by dark black fur.

“When we shot close-ups of Diggs, we had a Kino Flo BarFly on short stands on both sides of the dog with the light aimed into his eyes,” he says. “Sometimes, we had a third Kino Flo BarFly placed over the front of the camera to get catch light in the dog’s eyes.”

Poster used Kodak Vision 3 500T 5219, and occasionally rated the negative for an exposure index of 800 in darker settings.

“I also consistently used Tiffen Glimmerglass filters on lenses to help take the images a little toward fantasy,” he explains. That isn’t something you learn from reading textbooks about filmmaking. Every cinematographer does it differently based on their instincts and vision for the story.

There are scenes with 30 to 40 dogs in different places that were shot with a very large Motion Control crane that repeated flawless replication of moves and focus in order to create seamless splits during post-production. On smaller setups, a Libra remote head that could record and play back moves was used. A scene where the audience sees Doggie HQ for the first time with many dogs in the shot, required 56 passes in a hugely ambitious motion control shot.

Poster stresses that the collaborative process included cinematographers Brian Pearson and Roger Vernon who led the second units.

“They were invaluable colleagues who were able to finish off complicated scenes that had many small parts,” Poster notes. “There were several scenes that they shot from scratch. A talented second unit is great asset if they successfully emulate the style of shooting and match what the first unit is doing.”

"(Cats and Dogs: The Revenge of Kitty Galore) is an intriguing James Bond type story. After about 30 seconds, you believe the dogs and cats are smart and funny and that they really know how to talk."

- Steven Poster

Front-end lab work was done at Technicolor, in Vancouver. Poster took digital stills of all the various setups. He manipulated those images at night and sent them to the dailies timer as visual references for each scene. The lab provided digital dailies.

“It’s important to project dailies for movies that will be seen in cinemas on a screen,” he says. “This is the only way to understand the scope and scale of the movie you are making. It can be a simple and inexpensive process. We used a Panasonic AE3000 digital projector and either painted a white wall or had the grips build a simple frame and stretch fabric to make it into a screen. Every day at lunch, a regular group of us would eat in the dark and delight in our work from the day before.”

David Cole, the DI colorist at LaserPacific, in Los Angeles, got batches still photographs while the film was in production, to give him a sense of Poster’s vision for the look. He had a head start, because they had collaborated on six previous films.

More than 1,000 visual effects were seamlessly melded with live-action film during DI timing. The timed DI was converted to 3-D format.

“It was a painstaking process that began with converting key frames from each scene,” Poster says. “We sat in a big screening room wearing 3-D glasses, and told them things like, ‘That dog in the foreground needs to be more at the plane of the screen, and that object has to be a little further back. Bring that object off of the screen. Let the convergence fall a little further back.’ We guided them through every aspect of converting the images to 3D, and later analysed each shot in motion to see if any fixes were needed to make the scene work seamlessly for the audience.”