SOARING SHOTS

Challenged to create a deeply immersive environment that not only enhanced the actors’ performances but also remained true to the historical context of the series, Lux Machina collaborated with the team at MARS to develop bespoke solutions to bring the harrowing aerial combats of WWII to life.

Apple TV+’s definitive account of US aerial combat over Europe is the third WWII-based epic series after Band of Brothers (2001) and The Pacific (2010) for producers Steven Spielberg (Amblin Television) and Tom Hanks (Playtone). Presented by Apple Studios, the nine-part story follows the fate of the 100th Bombardment Group, a US Air Force squadron stationed in England and tasked with bombing Nazi-occupied territory in 1943.

The nine-episode series is directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, Dee Rees, Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck with cinematography from Adam Arkapaw, Richard Rutkowski ASC, Jac Fitzgerald and David Franco.

A primary goal was to recreate the missions B-17 Flying Fortress bomber crews with historical accuracy. Given the premise and verisimilitude of the series, virtual production was the obvious choice for capturing interactive lighting and reflections on the bomber during aerial combat.

Discussions began in 2021 when Apple called Lux Machina Consulting about a potential show and introduced them to VFX supervisor Steven Rosenbaum.

Conventionally, the LED volume is used for in-camera real-time visual effects but for Masters of the Air this was not the case.

Rosenbaum explains, “Typically, before going into a volume, you will shoot background plates for photoreal playback in the volume. To do that you want to know what the foreground action is going to be so you can compose plates accordingly. However, for scheduling reasons we didn’t have that benefit. So we played back previz in the volume, using aerial plates as reference, and matched them in post.”

He adds, “The goal was to create a deeply immersive environment that not only enhanced the actors’ performances but also remained true to the historical context of the series.”

The novel use of previz and realtime environments created a flight simulator experience for the talent including accurate lighting, reflections and layers of effects for explosions, smoke and tracer fire.

“It’s like an interactive experience on rails,” says Galler. “Typical VP environments are relatively static or use plates which have all the movement in them. We had a hybrid of the two. As the plane banked on the gimbal the environment reacted appropriately. It’s the first time at this scale we’ve combined a flight sim game-like experience with dynamic action that the ADs could call on. The whole approach made it feel more real.”

Lux began working with the Third Floor and Halon Entertainment to establish the shots that would be used in production. This included using a volume visualisation tool to create a unique design for production.

In early 2022, Lux began designing the specs based on an understanding of content and set layout. A machine room to power the whole enterprise and four ‘brain bars’ for the virtual art department (VAD) were built and tested in the US. Everything was shipped from LA, prepped in London and installed at the stage in Aylesbury.

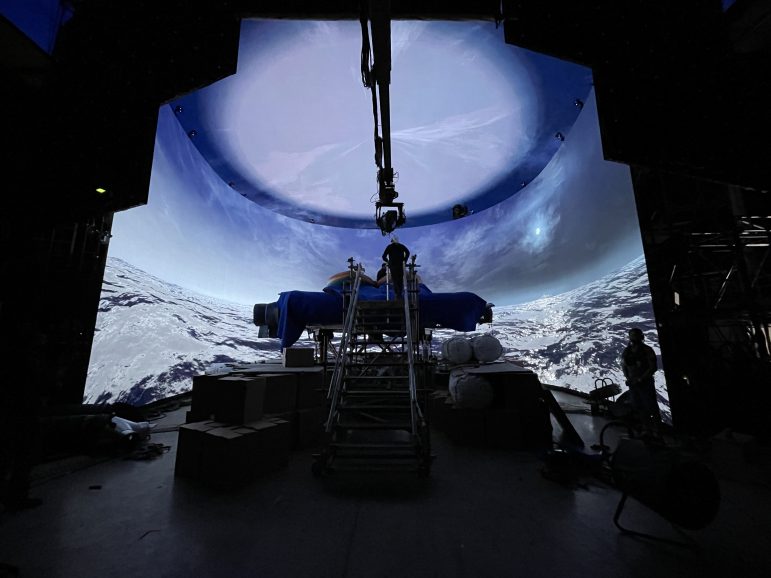

Volume stages

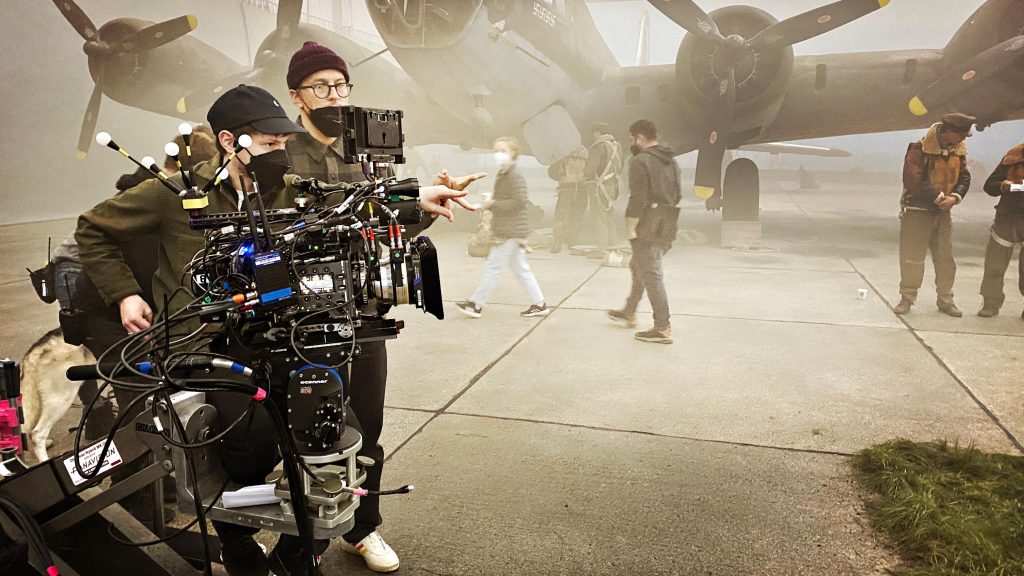

Masters of the Air was shot at Apple’s Symmetry Park in Buckinghamshire. The production used two soundstages equipped with custom LED volumes and a virtual production infrastructure that was constantly adapted to fit the needs of production. The first volume, used for 75% of the shooting, was a 40ft-wide, 30ft-high, 270-degree horseshoe. It featured an LED ceiling surrounding the cockpit, which was on a fully mechanical gimbal. The SFX team drove the gimbal while referencing content on the volume. The wings of the plane were extended into the virtual world on the screens and tracked with cameras and markers.

The second stage was a 110ft-wide wall and very little curvature and contained sets for the fuselage of the bomber. One side was surrounded by a large, curved wall with a lightbox above with DPs able to use more than 280 SkyPanels. The stage also housed a fully mechanised gimbal reacting to content in real-time.

A third volume was comprised of ramps and movable walls into an ‘L’ which could be quickly configured and used in a more ad-hoc manner. This was mostly used for the ball turret where a gunner could look down to a target, and occasional take-offs.

In partnership with the team from MARS, Lux Machina managed and operated all Volumes fusing the virtual and physical worlds by incorporating bespoke solutions and innovative technology and often shooting on all simultaneously.

Cameras

The production shot on Sony VENICE to take advantage of the Rialto Extension system which enables the sensor block to be mounted within the set tethered to the camera block on the gimbal. The camera’s high speed sensor readout also made it a good camera for VP.

Phil Smith, 1st AC, says, “We couldn’t have shot on the gimbal and in the replica B17 planes without using the Rialto. The director wanted the actors and action to take place in the actual spaces the B-17 plane has so this would give everyone a sense of what the actual pilots and crew had to experience. The planes were built to scale and the spaces in the interior of these plane were very, very small. Full sized cameras would not have physically been able to fit inside and get the angle and positions that they needed.”

Up to 16 cameras were running at one time with the feed calibrated to screens with Lux proprietary colour pipeline.

Galler says, “Our system allows for DPs to add their camera or lens back in. Instead of having to reverse out the lens and do all this other work, we believe that giving the DP the tools that they need to create the look that they want is the most important part because we’re trying to power their vision of the story.”

A Sony FX6, which shares the same sensor size as VENICE, was also used as a helmet camera and as a director’s viewfinder for checking out shots in the tight set without having to get the camera inside or bring the plane gimbal down. The DPs appreciated the camera’s skintones, colour reproduction and low light performance.

Syncing each camera with each other and the refresh rate of the wall was no small feat. Lux built a second MCR adjacent to stage to manage lens data, video input and sync over Timecode and Genlock.

The backgrounds were not frustum tracked but the position of the gimbal was. “We were not worried about multiple points of view. We chose a track very close to the centre of the action, i.e. the centre of the cockpit, aligning a position from the perspective of the talent as opposed to the perspective of the cameras. All cameras were synched to the movement on the wall from that perspective.”

Lux worked closely with the DP and lighting technician to synchronise the DMX with the real-time content. Lux operators were able to facilitate creative requests from the DP and Director instantaneously providing flexibility and creative freedom on the day.

Lux led the supervision and production of what turned out to be around 80 environments over the course of seven months of shooting starting in summer 2022.

Lux and the MARS team of software developers also worked in a custom version of Unreal Engine building 50+ proprietary virtual production tools specifically for challenges faced on the show.

“This was needed to provide more seamless integration of a traditional production into a virtual production,” says Cameron Bishop, MARS’ lead Unreal operator, who was instrumental in some of the tool development.

These included a light card tool to enable lighting operators to interface with light cards in Unreal, controlling size, shape, opacity and colour temp. Gaffers were also able to control a ‘programmable sun’ with historically accurate positioning. On the second volume a series of interactive lighting machines were dedicated to driving the pixel-mapped SkyPanels.

“If the gaffer wanted to add another 100 SkyPanels then we needed a way of providing this quickly and efficiently in Unreal,” says Galler. “We adopted a process akin to how a lighting programmer would create a connection to those lights that allowed us to be much faster in set up and more adaptable. The lighting programmer could take over a block of lights while VAD could also drive content to screen which gave us very interesting layering effects that otherwise would be very difficult to achieve.”

These included real-time ‘flack-triggering’. Bishop elaborates, “As an example of being agile to director needs, it became clear we needed a real-time ‘flack-triggering’ solution. We developed a tool that allowed us to simulate explosions on the LED volume with the press of a button. This provided instant feedback to the director, and in turn helped the actors believe the danger their characters were in.”

Immersive for realism

Lux and VFX teams spent hours in prep providing solutions to the smallest detail. What colour is a flare? How big is it? How much light is it going to throw into the cockpit? Where is that plane going down? How much smoke is coming out of the fuselage? What’s the cloud cover? Where is the sun right then?

“All that would have been so difficult to do or imagine in green screen,” Galler says. “In many ways it was like working on location. The actors felt the lighting and interactive elements really impactful in their ability to connect with the story because it added to the illusion that they’re really there in the cockpit. They felt connected to the environment in a way I don’t think was possible on a green screen stage.”

Holistic collaboration

Associate VFX producer Will Reece says VP is a holistic way of approaching production. “It’s not a tag onto VFX or any other department. It’s how you structure your production, and that needs to go from the top to the bottom for it to ultimately be as successful as possible,” he says. “Everyone in the crew has to buy into that. We were so fortunate to have a strong presence from Lux Machina Consulting on the ground who spearheaded support and ongoing education during production to help us think about or approach things differently.”

VP producer Kyle Olson says, “From the dynamic volumes on our UK soundstages to the intricate cockpit and fuselage sets, every element was designed to ensure historical accuracy and interactive realism. This project was not just a technological triumph but a testament to the power of collaborative storytelling.”

“It was a real pleasure to strengthen and support this production and be part of the biggest VP crew either company has worked on” comments Rowan Pitts, founder of MARS Volume. “The mutual respect that the teams displayed and desire to overcome challenges with agility and collaboration no doubt forged the success on set.”