Fight the Good Fight

Special Report / What future for Celluloid?

Fight the Good Fight

Special Report / What future for Celluloid?

BY: Adrian Pennington

Technicolor's cessation of all photochemical activities at Pinewood by the end of the month has galvanised UK filmmakers, including the BSC and Directors UK into redoubling efforts to preserve celluloid as an origination medium, writes Adrian Pennington.

There are fears that the withdrawal of lab processing capacity from UK shores will impact decisions to shoot here and result in substantial loss of inward investment.

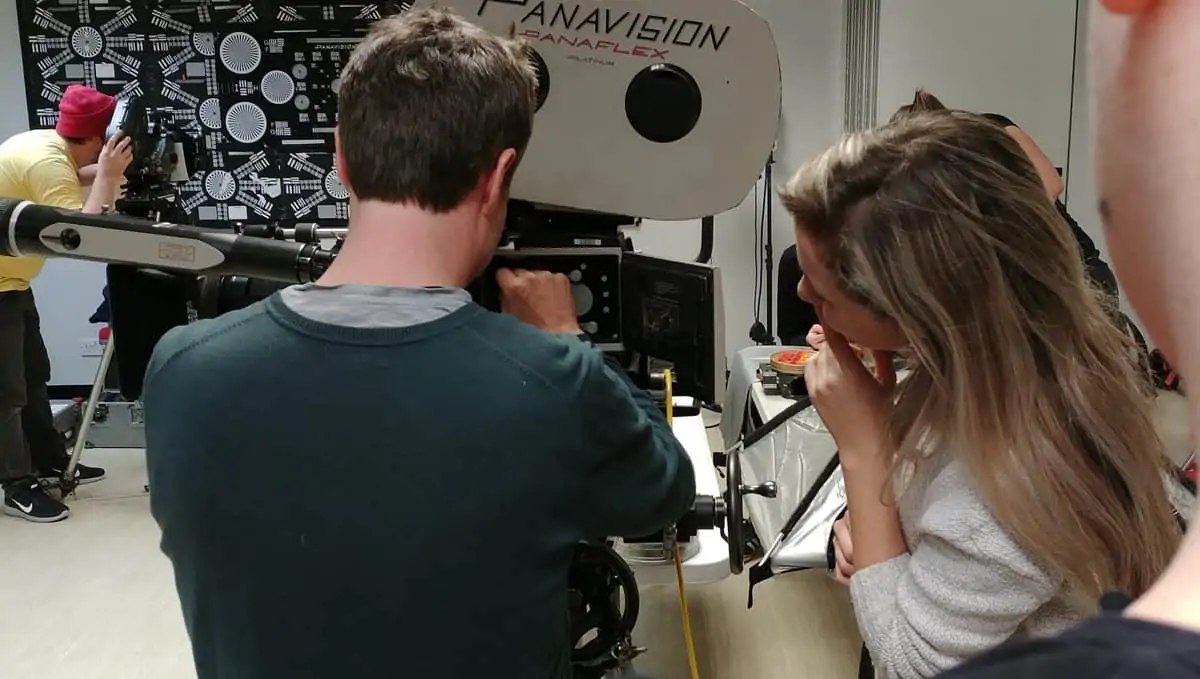

Led by the BSC and Directors UK, with the support of Panavision, a campaign to lobby Warner Bros., Deluxe and to alert the BFI and film policy maker DCMS, has gathered pace.

“We want to declare our support for continued film processing in this country, for the creative choice it allows directors and DPs, and for wider industrial and economic reasons,” explained Directors UK film chair Iain Softley.

The initiative has the backing of directors including Kevin MacDonald, Michael Apted, Ken Loach and Jane Campion as well as BSC members including John de Borman, Haris Zambarloukos, Danny Cohen, Barry Ackroyd, John Mathieson and Andrew Dunn.

“We are trying to make sure that all parties are aware of the filmmaker's strong desire to continue working on film,” said Softley. “This is not a fringe issue but one that is central to the fatality of the film business in this country. We are expressing the experience of very eminent filmmakers.”

It is a fast-moving picture. An early victory for the campaign has resulted in a deal between Deluxe-owned Company3 and boutique lab iDailies, which will see all CO3 16mm and 35mm projects – including Disney's Cinderella directed by Kenneth Branagh, and shot by Zambarloukos – transferred at its facility and processed at iDailies.

Deluxe, owned by Ronald Perelman’s MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, had previously subcontracted its 35mm/16mm colour negative processing to Technicolor at Pinewood. The CO3/iDailies pact does not represent a reversal of the company's wider policy of shuttering uneconomical labs worldwide.

“It's one thing to base decisions on the global needs of a huge corporation and another in identifying the needs of clients which we see on a daily basis,” said Patrick Malone, director of digital film services at CO3. “Despite the understandable and inevitable fact that a huge lab can't be sustained in this day and age, there is still a very real need to support those filmmakers choosing to shoot film.”

The Ealing-based iDailies will increase capacity from 40,000ft to 100,000ft with the addition of a new chemical bath. It will also develop B&W, answer prints and deliverables in conjunction with Company3.

“It's likely that filmmakers reluctant to switch to digital will revert back to 35mm if they are made aware of an opportunity to do that,” said Malone. “A lot of people have the wrong impression that film is dead. It clearly is not. Filmmakers do not have to turn away from film.”

While welcomed by Directors UK and the BSC, even this capacity may not be enough to secure the mid- to long term future of 35mm acquisition on home soil. A second UK lab, possibly underwritten by Warners Bros., is under consideration by the studio.

“If a heavy-hitting director, like Steven Spielberg or Christopher Nolan, wants to shoot on film, the tax break alone will not be enough to lure them to the UK,” said Softley.

BSC president John de Borman commented, “Deluxe, Warner Bros., Panavision and ourselves are worried about losing revenue from major productions which may decide not to come to this country if the only processing option is to send dailies overnight to France.”

Warner Bros, which has ploughed £100m into Leavesden Studios and plans to house up to six major film projects there over the next two years, is weighing the merits of locating a lab on-site to secure its own investment by guaranteeing a throughput of work.

“This is not a digital versus film battle,” stressed de Borman. “Investment is also about the UK's digital post production expertise. But we cannot exclude film. All we are fighting for is a choice between shooting digital or film or digital and film. Cinematographers are extremely concerned that suddenly three quarters of our palette could simply disappear.”

“The main drivers are the studios who pay the labs wages,” says Softley. “If they want it to happen it will. At the moment there is a big effort from them to secure the future of film processing labs in the UK. Because things are at a delicate stage no one is wanting to be drawn on the details. However the end of processing is not a fait accompli.”

Filmmakers are caught between financially unviable large-scale film processing, where the bulk printing business has collapsed, and the uncertainty surrounding the fate of Kodak, almost the sole maker of motion picture materials.

“In 2009/10 the UK market was peaking at around 350,000ft of negative a day but there has been an extremely marked decline since then,” explains Claude Gagnon, president of Technicolor's Creative Services. “When you look at the volume today and projects over the next few months I'm not sure if there's more than 25-30,000ft of negative a night. When the volume drops by 85-90% you can't expect to process film at 2009 prices. With that in mind, it's clear that a film lab like Technicolor or Deluxe simply cannot operate.”

He continues: “The Technicolor lab at Pinewood had capacity for 150,000ft a day, but when only 10,000ft a day is coming through, financially it didn't make sense. Also, you risk losing the consistency in processing quality that comes through maintaining an extremely organic entity like a film lab operating at capacity.”

Both Deluxe and Technicolor had hefty lab real-estate on their books, built for bulk release print rather for front-end work. “When you have massive infrastructure and your bulk release has been evaporated, economically it just doesn't work,” says Gagnon, who adds that Technicolor is exploring niche lab operations.

The long-term viability of motion picture film for origination is compounded by Fujifilm's ending of negative and print stock manufacture (March). Although Kodak expects to emerge from bankruptcy protection later this year, analyst Michael Karagosian suggests that it will be operating at just 10-15 percent of its former total capacity.

Kodak disputes this figure. “We don’t have a crystal ball, but Kodak continues to manufacture and supply billions of feet of film, and the plan is to continue to do so as long as there is customer demand,” says Johanna Gravelle, Kodak's worldwide marketing director, Entertainment Imaging.

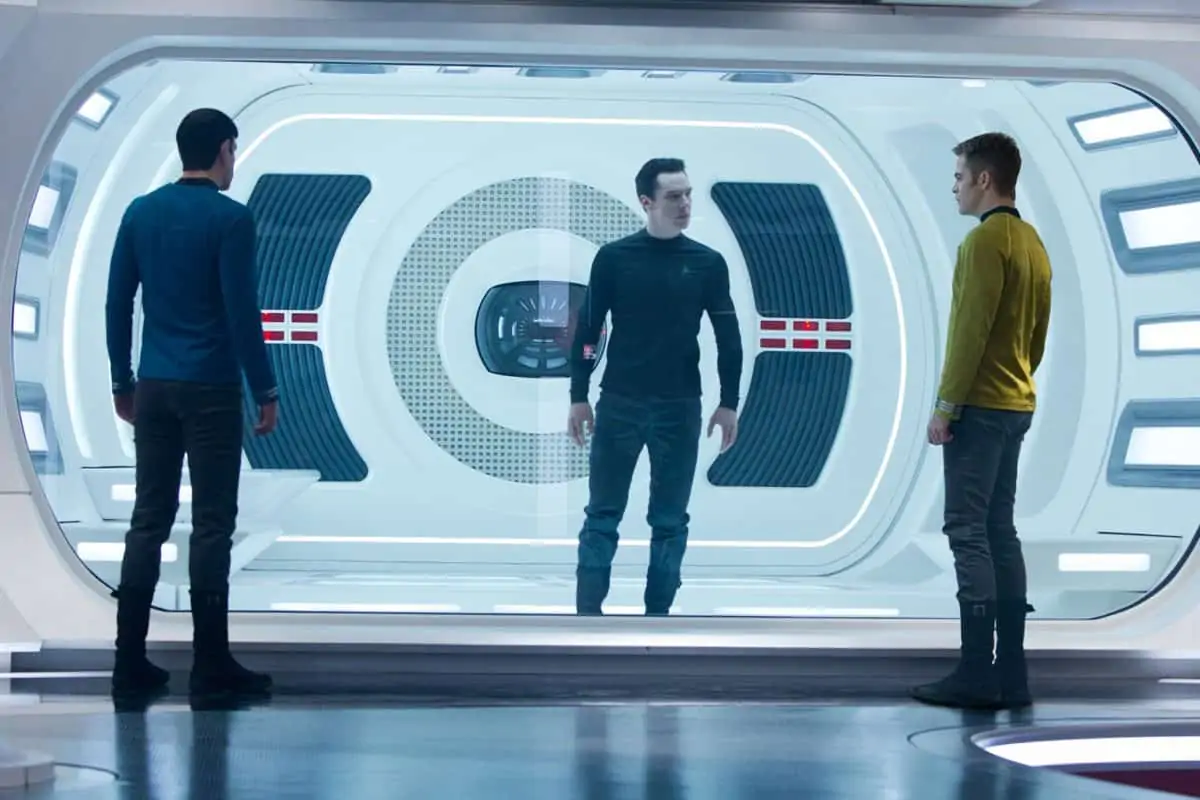

The company points to dozens of labs worldwide still processing, and to tentpole 35mm features recently released or in production including Star Trek: Into Darkness, Man Of Steel, Amazing SpiderMan 2, The Lone Ranger and Fruitvale.

“We’re not going to limit the possibilities by putting a time frame on it [manufacturing],” states Wayne Martin, Kodak's general manager for Image Capture & Distribution. “We’re planning to supply film as long there is demand in the market.”

"This is not a fringe issue but one that is central to the fatality of the film business in this country. We are expressing the experience of very eminent filmmakers."

- Iain Softley

The UK's only other 35mm laboratory is Bucks Labs, a member of Kodak's Imagcare Program. However, Hampshire's Black Hangar Studios is looking to invest in a direct-to-print machine and mini-lab by the end of the year, according to facility manager John Ross. Black Hangar is co-owned by Jake Seal founder of digital cinema mastering group Carousel Media.

“We see a huge demand for film services, such as subtitling which we would introduce without the high overheads of traditional labs and without dramatically increasing the print cost,” says Ross.

Matters are the same, if not worse, in the US where Burbank's Fotokem remains the only major facility processing 65/70mm, 35mm, and 16mm motion picture film. Cineworks closed its Miami lab last year and its New Orleans operation may soon be forced out of business.

“Nobody is fighting back,” reports Roberto Schaefer ASC, AIC. “Everybody thinks that we must not be seen as old timers, that we must embrace new technology and that we can complain all we want but nothing will change.”

John Bailey ASC, agrees: “Everything is driven by the bottom line. The creative community alone is unlikely to influence corporate policy unless we continue to choose film in sufficient quantity to make it profitable.

“I believe an important part of the strategy is to excite students and emerging filmmakers to the artistic and unique experience of creating images on film – and for those of us who continue to chose film, to create a sense of film magic that we can transmit to those 'born digital.'”

The UK campaign to save celluloid runs in parallel with attempts to get the BBC to review its decision, six years ago, to outlaw 16mm/S16mm as delivery formats for HD TV programming. These technical guidelines also run across the Digital Production Partnership (DPP) agreed by ITV, Channel 4 and BSkyB. At the time of that decision, IMAGO, led a fight, supported by the BSC, which initiated a series of comparative tests. Major companies, headed by ARRI and Panavision, attempted to provide an objective appreciation for cinematographers and directors of the true cost of the digital or film dilemma through the Image Forum, which also had the backing of Kodak, Fuji, Technicolor, Deluxe and several London facilities. However, the DPP’s decision remained in place.

Now faced with the loss of laboratories in the UK, directors Paul Greengrass, Ken Loach, Stephen Frears and Lynne Ramsay are among 32 signatories to an open letter to BBC Creative Director Alan Yentob calling for an immediate review, “to be conducted in a transparent and inclusive manner with appropriate participation from industry professionals, and for due weight to be given to creative as well as technical considerations.”

Further weight can be added to the cause by the recent success of the German cinematographer’s society, the BVK, in having 16mm film being accepted again in Germany as an appropriate means of acquisition for HD-TV programming. However, in light of the BBC's unequivocal statement to British Cinematographer, the latest bids would seem futile.

“Our position, and the position of the other DPP members, hasn't changed. Super 16 is not HD,” said head of technology HD & 3D, Andy Quested.

The matter is now something that should be “shouted from the rooftops, we have to stand up and be counted” says de Borman. “Let’s hope we are not doing so too late. We have to try to make sure that as many people as possible hear what we are saying and why, especially producers”

The film versus digital debate often boils down to cost, where the perception is that digital is cheaper. For many this is an erroneous argument that does not account for the high cost of digital post production, nor for the proven 100-year security that 35mm provides as an archive medium.

“The issue with production budgets is that they rarely contain all the extra costs involved in digital capture and output in their entirety, not to mention the ongoing storage and archive issues that are commonplace,” says Phil Méheux BSC. “All of which add cost to the overall production budget. It’s fair to say that, although it can vary from production to production, there is not a lot of difference by the time the film hits the screen.”

He continues, “I'm sure a lot of the more experienced cinematographers would prefer to shoot on film given the choice – certainly those that have learned their trade before the advent of digital capture. However, we have to rely on support from the director and of course, the producer, which sometimes is not forthcoming. It should be a choice for the individual production and approach.”

While waiting on a decision from Warner Bros., the next steps for the campaign include invitation of “as many producers as possible” to a town hall meeting organised by the BSC, in partnership with the Directors Guild, “to lay bare once and for all the actual financial cost of shooting on film and shooting digital or a combination of the two from start to finish,” says de Borman. “There is a negligible difference and it is vital that we stand up and make this economic case as much as the creative one. The choice of the look of any film has to be based on keeping, and not losing, the varied visual palette available to us and stop blindingly limiting it.”