Gold Standard

Special Report / How can cinema survive?

Gold Standard

Special Report / How can cinema survive?

How can cinema technology keep pace with the exciting large screen, high-resolution and on-demand visual experiences promised in the home? Adrian Pennington reports.

“The industry's biggest fear is that technology in the home is rising faster than the tech in the cinema,” admits Howard Lukk vice president, Production Technology at Walt Disney Studios. “So how do we make the cinema experience the premium experience?”

His question comes at a time of considerable debate surrounding the visual characteristics of the successor format to HDTV. Resolution at four times HD (i.e. 4K) may be key, but there are strong arguments for a production and presentation standard which delivers a more compelling visual experience than just a polished version of what consumer's already have.

For Chris Johns, chief engineer at BskyB, which is testing the technology, the shopping list of attributes includes, “no interlace, more resolution, finer pixels, improved motion portrayal [anywhere between 60-120-200fps is talked about], greater dynamic range and more colour. We also need to think about new, object-based audio, which manipulates the audio according to the environment you are sitting in. Ultra HD has to deliver a new viewing experience.”

To feel the benefit of 4K Ultra HD viewers are required to buy much larger home TVs – moving them one step closer to the multiplex.

Ericsson's Giles Wilson describes Ultra HD programming as "moving from viewing to experiencing” and predicts that if one operator launches in any market “then the question for other broadcasters becomes 'can I afford not to move to Ultra HD?', because consumers will go where the most compelling user experience is.”

Even the iPad 4, Playstation 4 and the new Xbox One console support 4K and, further out, plans are fomenting, in Japan at least, to air the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games at sixteen times HD resolution.

Why does all this TV tech matter? “Bluntly, we are in an arms race with other leisure experiences,” says Phil Clapp, president of the International Union of Cinemas (UNIC), speaking at IBC. “The cinema industry must be like a shark: moving forward, otherwise it won't survive. We need to keep cinema at the cutting-edge.”

“Exhibitors are quite simple beasts,” he adds. “We always ask some fundamental questions: will new technology make a difference for our customers, and will they even notice it, and if they do notice it, can I make money out of it? Will any new technology save me money? Can I market the benefit as a gold standard to boost the cinema-going experience?”

There are a number of technology options being discussed among studios, exhibitors and standards bodies like SMPTE to help set the visual bar higher then ever.

Tech options on the table

These include higher spatial resolution, larger colour space, extended dynamic range, improved temporal resolution, improved compression and laser projection. Which, if any or all, of these meet Clapp's criteria?

Taking resolution first, an increasing number of films are being acquired at 4K with practical applications in post production assisting crisp colour keying and image scaling. Most grading and VFX work, though, is made with 2K proxies, and most DCPs are 2K even in 4K projection theatres. Rises in computing power and reduction in cost will inevitably make a 4K lens-to-screen pipeline widespread, but the issue is whether audiences will actually see the difference.

“The projection resolution needs to recognise what the human visual system can actually resolve,” says David Monk, CEO of European Digital Cinema Forum, and lecturer on visual perception. “The cost of the resolution (to implement from capture-to-screen) probably exceeds the value to the viewer, especially if you are sitting way back from the screen. The same is true for cinema or TV. Going beyond 4K in an auditorium environment is a total waste of money.”

A greater amount of data captured at the lens also makes it possible to boost dynamic range (contrast ratio) and to widen the colour gamut.

“To see the difference between HD and Ultra HD you have to be standing quite close to the screen,” says Wendy Aylsworth, SVP technology at Warner Bros. Technical Operations - and president of SMPTE. “With dynamic range and broader colours, you can actually see those across the room.”

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) is one body pushing for greater colour consistency. AMPAS' ACES look management scheme doesn't throw any detail away, according to Andy Maltz, Director Science and Technology Council.

“You have what the camera saw. You get more colour if you increase the dynamic range. Instead of clipping toward white, the colours will keep on going in a higher dynamic range display.”

He argues: “High maximum light levels give us better highlights and better depth cues that result in a broader visual palette which filmmakers care about.”

High frame rates (HFR) are believed to smooth motion blur and provide a more intensely realistic visual. The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey introduced HFR to mainstream audiences and will repeat the trick when sequel Desolution Of Smaug releases at Christmas 2013.

While Sony European sales director for Digital Cinema, Oliver Pasch warns, “the subtleties of 48fps are probably lost on the wider audience”, others believe the format needs better marketing.

“The industry as a whole failed in the way it marketed HFR to consumers,” declares Clapp. “As a result of that the audience response was mixed. Where it was locally marketed not only did HFR drive audience numbers but exhibitors were able to charge a premium for it.”

Richard Welsh, Technicolor head of operations, Digital Cinema, and SMPTE board member, suggests HFR still has much to offer and that it’s largely a problem of conditioning.

“HFR seems to enhance audience response to colour, which may be a result of the brain having to work less hard to fill in missing motion information between frames,” he says. “Many high-end computer gamers are regularly playing games at 120fps or higher. James Cameron’s Avatar sequel will be shown at 60fps. My guess is that HFR will be here to stay and that the standard, when it is used, may be higher than even 60fps.”

Projected by laser

There are more prosaic things that can be done to improve the visuals – cleaning dirty projection windows and lenses, for example. Certainly upping the light levels is another incremental advantage with proponents claiming that laser illumination will not only lift stereoscopic films from their current gloom but offers other advantages too, including reduced power consumption compared to xenon lamps.

While Sony won't have a laser projector ready until 2015, Christie Digital's system is expected early next year and NEC has already launched one, albeit that laser technology still has to satisfy the safety concerns of regulators in the US and the EU.

“Laser projection will be considerably more expensive than xenon-lamp projectors and, therefore, will be adopted first at premium, high-grossing sites which already offer 4K or high-specification audio or giant-format experiences,” Don Shaw, Christie’s senior director of product management told this author at CineExpo.

There is even the prospect that the cost to the exhibitor of installing lasers could be offset by premium box office tickets and a “projected by laser” brand awareness.

“Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with, provided it can deliver them a new experience,” said Shaw.

It's unlikely that any of these factors, from greater dynamic range to laser-illumination, will make any difference to audiences, if introduced alone. SMPTE and the studios are inclined toward moving forward on all characteristics hand in hand, but it's a slow process. Any change needs a revision of the Digital Cinema Package.

Since the forced division of Hollywood majors from their theatre chains in 1948, exhibitors have had responsibility to back the right technological horse. With Digital Rollout nearing completion worldwide, and without a Virtual Print Fee to subsidise the cost of purchase or lease of new theatre equipment, there is a real question mark against who pays for further technology.

“Exhibitors have spent money on new digital projectors and are now being told that they have to upgrade again or worse, that they need a whole new projector system,” says Clapp. “That is a difficult sell in this economic climate.”

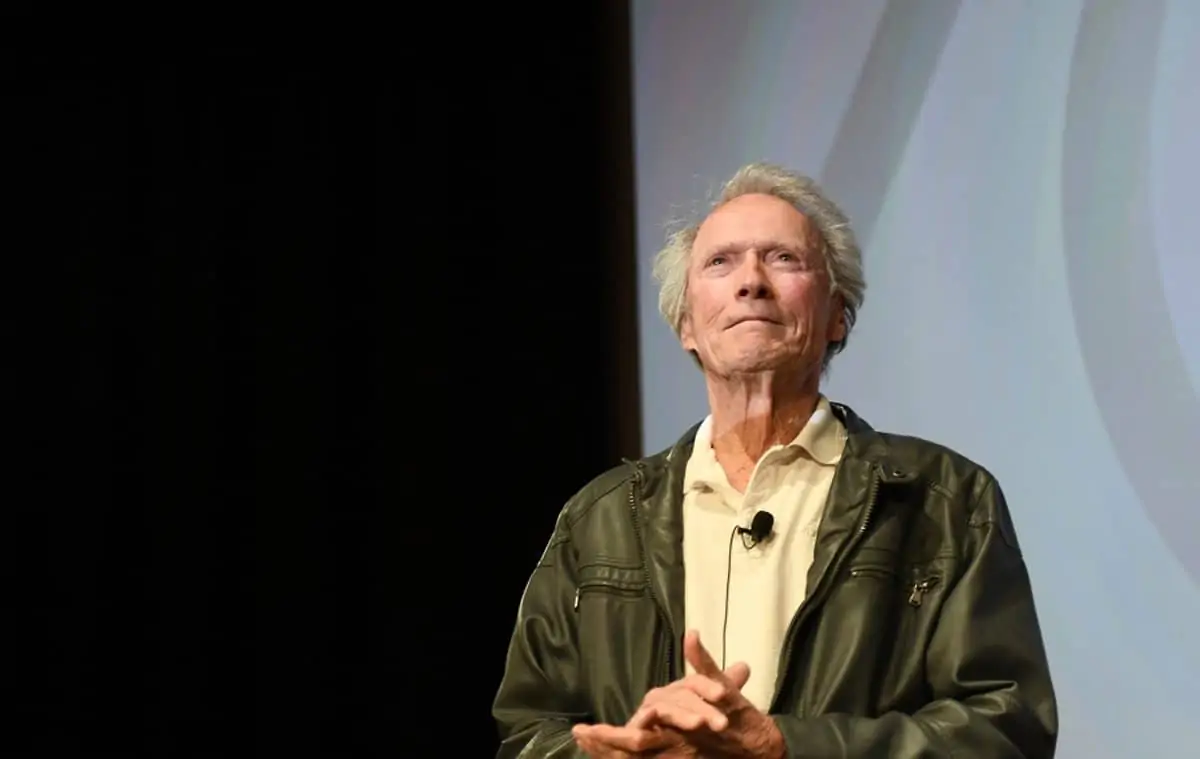

"The industry's biggest fear is that technology in the home is rising faster than the tech in the cinema."

- Howard Lukk

Event cinema, tailored to audience

Exhibitors might eye alternative content as a means to increase revenue and make better use of existing theatre infrastructure. Estimated at $300m worldwide today, 'event cinema', as it is being branded, is predicted to achieve $1bn by 2020 [IHS Screen Digest] and has already become a “viable revenue stream for exhibitors,” said Melissa Keeping chair of trade body Event Cinema Association (ECA) at CineExpo, Barcelona in June.

The November 23, 2013, simulcast of Dr Who's 3D, 75-minute, 50th anniversary episode in UK cinemas, with a broadcast on BBC One and networks worldwide, is one upcoming example. Next year the FIFA World Cup Final could be transmitted live in 4K to global cinemas from Brazil.

Another avenue of alternate uses of theatre space, which neatly ties in competition from second screens, has just launched in the US.

Disney are encouraging young audience members going to see the re-release of The Little Mermaid to interact with the on-screen action via the iPad app Disney Second Screen Live. Used while the film is playing, the app encourages sing-alongs with the soundtrack, and delivers games based on the story plot and behind-the-scenes information.

The app has been available for home use for the past couple of years, working alongside the Blu-ray releases of Tron: Legacy, The Lion King and Pirates Of The Caribbean.

“We've had some successful trials of second screening, but it only works for repeat customers of a movie they have already seen,” explains Lukk. “It won't work on new features because it's a big distraction to other customers. I wouldn't even consider it a theatrical experience. People love it, but they don't come with a cinematic expectation.”

Lukk points out that for second screening to take-off, the “woefully inadequate” theatre infrastructure has to be upgraded: “Imagine the WiFi you need for 200 iPads,” he says.

Anathema as the idea may be to a filmmaker's traditional understanding of cinema, the audience demand for this type of engagement shouldn't be ignored.

“We have to think about product placement with databases of on-screen action linked to iPads,” says Clapp. “It's about taking metadata out of the projector - like timecode - and creating a new participatory experience. There are some opportunities to make second screen interaction a deliberate part of cinema going.

Greater dialogue

“We are only in the foothills of our understanding about how we engage with audiences,” he adds. “Exhibitors have observed a fairly monolithic business model and digital allows us to have a conversation with the audience.”

Iain Smith, revered British producer with a track record stretching back to The Killing Fields (1984) and on to Alexander (2004) and Children Of Men (2006), believes two distinct forms of cinema will emerge.

“Large, deluxe screens will survive because people want that communal Saturday night experience,” he says. “At the same time, smaller cinemas will provide a more diverse menu tailored for local audiences.

“In the past going to the cinema has been a bit like church,” he adds. “The congregation was invited in by a priesthood who would allow them to experience the mystery. Now cinema has more of the feel of a baseball stadium.”

This is no bad thing, Smith feels, and is in any case inevitable. “The industry needs to have a better dialogue with the audience,” he says. “There will still be the need for a storyteller's particular point of view, but how it is delivered and consumed will change.”

It is not just TV technology that is upping the stakes, but content made for TV too has shifted the balance of power in Hollywood. Dramatic series from HBO (The Wire, Game Of Thrones), AMC (Mad Men), Sony Pictures (Breaking Bad), Showtime (Homeland) and Netflix (House Of Cards), attract A-list talent and create mass social media buzz, putting cinema output in the shade.

“Cable TV has discovered that there is a need for quality storytelling that is not being satisfied by current $100m blockbuster tentpole movies,” observes Smith. “Netflix, HBO, Amazon and Google will become increasingly important in financing original drama for output over their networks. The two-hour cinema format is like a short story whereas the cable TV networks can expand on character and performance much more akin to a novel. The richest producers in Hollywood are not those working in film. There is a real business in TV.”

The traditional windowing of release dates, which preserves cinema as first in line, may change also. Features such as Ben Wheatley's A Field In England was simultaneously premiered live on Channel 4, screened in cinemas and on YouTube earlier this year.

“More and more films will bypass the big screen, but the power of the theatrical release is still important to drive distribution,” says Clapp.

Stakeholders from SMPTE to the Hollywood majors and distinguished producers like Smith are not concerned that cinema as a place to view films is about to implode. However, comments by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas earlier this year, which warned that the failure of too many summer blockbusters could spell an end to the way Hollywood does business, shouldn't be dismissed.

“The content is not good enough and I wouldn't be surprised if we see fewer tentpole movies greenlit in future,” notes Smith. “I think there is an inevitability about change which will ultimately be for the benefit of cinema. Cinema has to become much more of an interactive experience for the audience than it ever was before.”

Perhaps cinema will evolve into luxury screening rooms with sofa-beds and table service. Perhaps the IMAX model of giant screens or even Cinerama screens with a 180-degree or greater wrap-around of visuals will come into vogue. Giant OLED screens capable of displaying high-contrast and super-vibrant colour may eventually be possible. Howard Lukk's best guess for when autostereo cinema-sized screens may arrive is in thirty years.

“The aim is to take technology to the limit of what we can see and hear,” says Welsh. “We are trying to make cinema a more immersive experience, which in the future may be more like the holodeck on Star Trek – holographic rather than stereographic.”

Ironically, the single thing that will make the biggest difference right now to the perception of the picture, is better sound. “You put in cracking sound, and the pictures look better,” he suggests.

There are several competing, next-generation sound systems, most notably Barco's Auro 11.1 which is backed by DTS Multi Dimensional Audio, and the Atmos system from Dolby. Theatre owners and studios have asked for a common file format for immersive sound in DCPs in order to protect their investments in new sound systems, but with a potential goldmine for the audio system that can monopolise the future of cinema sound, this is one battle which has barely begun.