CREATIVE FORCE

If Sir Roger Deakins’ career was a screenplay, it would have all the thrills and wow factor of a sure-fire hit movie. Now a knighthood can be added into a narrative already infused with originality, ingenuity, and award-winning creations. The master craftsman shares his valuable insight and discusses filmmaking highlights, creative influences, and a long-standing passion for collaboration.

“Filmmaking is as much about the experience of working with wonderful people as it is the final result. That collaboration and what you can achieve together as a group is so special,” says Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC, reflecting on a craft and creative process he adores.

“I think I have been incredibly lucky. I don’t believe I’m a natural cinematographer – I’m quite private, not very confident, and not really a people person. I have been a bit bloody-minded in my choices though – I haven’t worked on a film unless I felt in some way emotionally involved. Sometimes I just can’t connect with a script and other times I’m five pages in and I might have to go somewhere but I just can’t stop reading. That’s when you know it’s a film you really want to get involved with.”

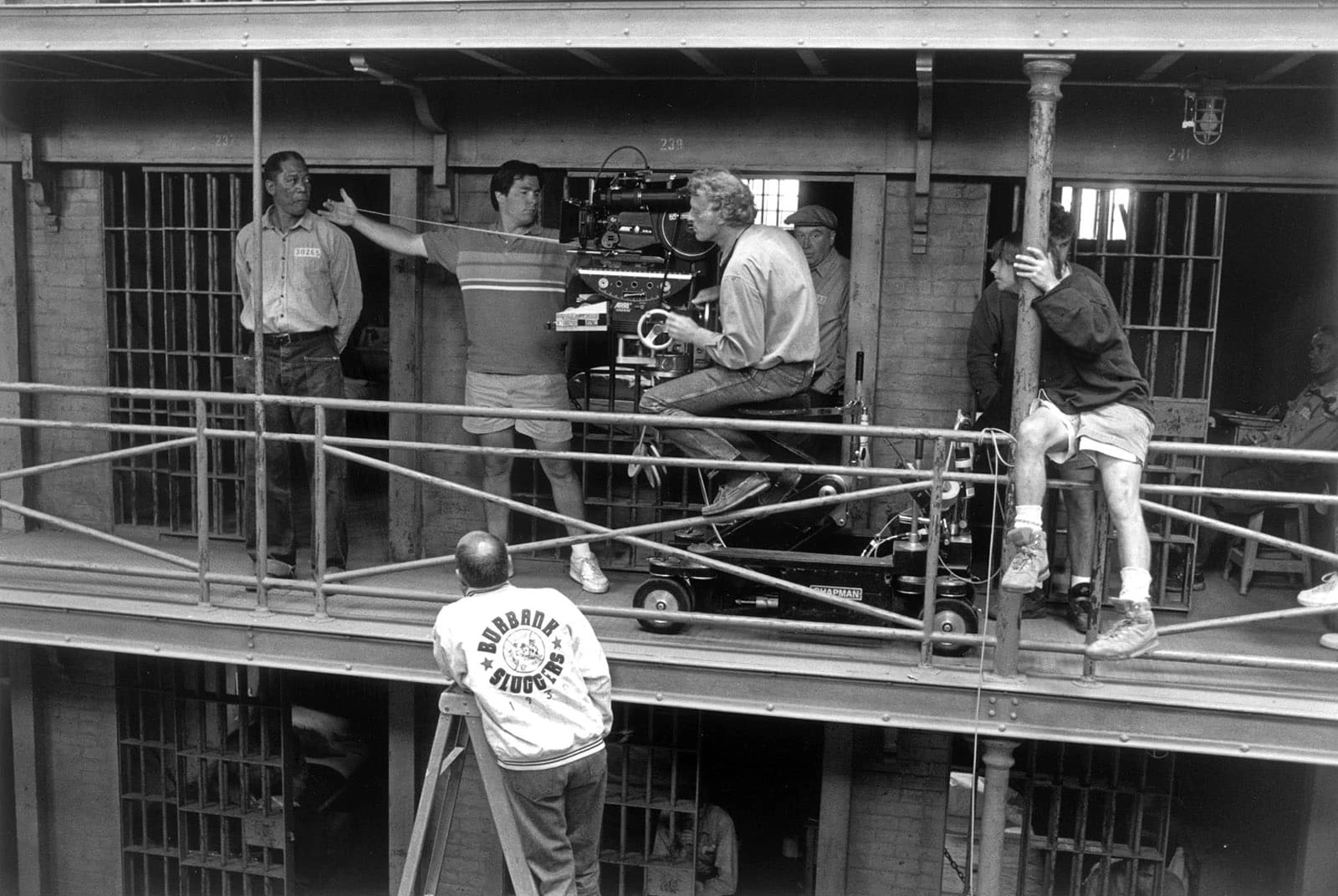

Deakins’ humility, wisdom and pure passion for film and the talented people at the industry’s core resonate through every word he speaks. Despite referring to himself as neither a people person nor a confident character, the cinematographer has formed many successful filmmaking relationships. These exceptional collaborations have produced some of the most revered and treasured masterworks in cinematic history,from iconic creations such as Fargo, 1984, The Shawshank Redemption, A Beautiful Mind, and The Big Lebowski through to Academy Award-winning productions Blade Runner 2049 and 1917.

Born in 1949 in the seaside town of Torquay in Devon, England, Deakins’ earliest memories of the magical flickering light of a projector in a darkened room include watching Felix the Cat cartoons at age six on his father’s 9mm projector and immersing himself in the movies screened at the local film society. “Those experiences really stayed with me,” he says. “The film society often showed us films prior to their release – movies like Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1966) which was banned for 25 years. I was one of the fortunate ones to see it. At that stage, I never connected films which I grew to love with a career.”

Spending his formative years in picturesque Devon, fishing with his father and exploring the rugged landscape also made a lasting impact. “That experience of the natural world had an effect on me, but I knew I didn’t want to stay in Torquay long term, so I applied to art college because I spent much of my time painting at school.”

Whilst studying graphic design at Bath Academy of Art, Deakins realised his passion for stills photography was stronger than his desire to paint, partly motivated by photographer and guest lecturer at the college, Roger Mayne. “He was a wonderful photographer and a great influence. He sent us out on the streets to take pictures and I would also head to seaside towns like Bournemouth, where I felt most comfortable. That’s when my love of the photographic image grew. I just enjoy the experience of trying to capture a moment – there’s something really personal about it.”

A chance conversation encouraged Deakins to explore the possibility of evolving this love of stills photography and pursuing a filmmaking career. Inspired by a friend at art college who mentioned he was applying to study at the soon-to-open National Film and Television School (NFTS) in Buckinghamshire, Deakins followed suit. With a growing interest in documentary photography, he hoped film school would present an opportunity to work in documentary filmmaking.

“We applied and neither of us got in,” he says. “When I asked why, I was told they wanted people with ‘a bit more world experience’ and that I would stand a good chance if I applied the following year.”

Undeterred by the rejection, Deakins worked as a photographer for a short while, documenting North Devon’s rural lifebefore reapplying and being accepted into the film school. “It was like a microcosm of the real world because you often had to talk your way into getting onto students’ crews. You had to be collaborative and develop people skills, something I never had as a child. I was very shy – I probably still am. The most important thing for me was being with people and gaining confidence in my own ability,” says Deakins, who has been named an NFTS Honorary Fellow.

“I don’t think I would be in the film industry now if I hadn’t gone to film school. It’s a different world now though and there are more opportunities, but you still need to want to practice and find your own way of doing things. I don’t think you can learn from somebody else – it’s an inherent and internal way you see the world that you then develop through practice.”

PRECIOUS LIFE EXPERIENCES

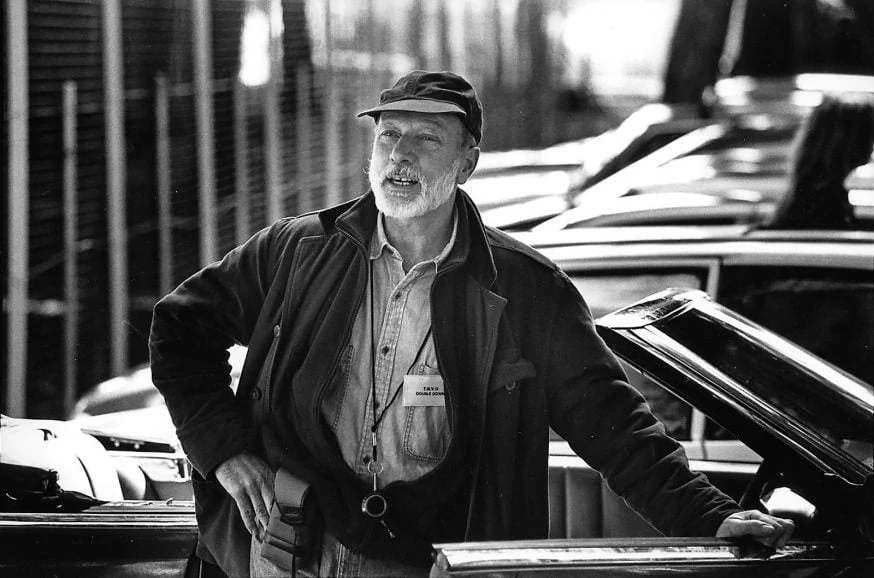

Deakins’ natural passion for camera operating and storytelling saw his filmmaking career begin to flourish in the realms of documentary. Based on a recommendation from friend and fellow filmmaker Chris Menges BSC, Deakins captured the Whitbread around the world yacht race in Around the World with Ridgeway (1978).

“I had to train to be one of the ship’s crew members as well as being a cameraman. Even though I spent much of my youth in a 16-foot boat with my dad, I had done very little sailing, so to set off around the world in a 57-foot ketch for nine months was incredible.”

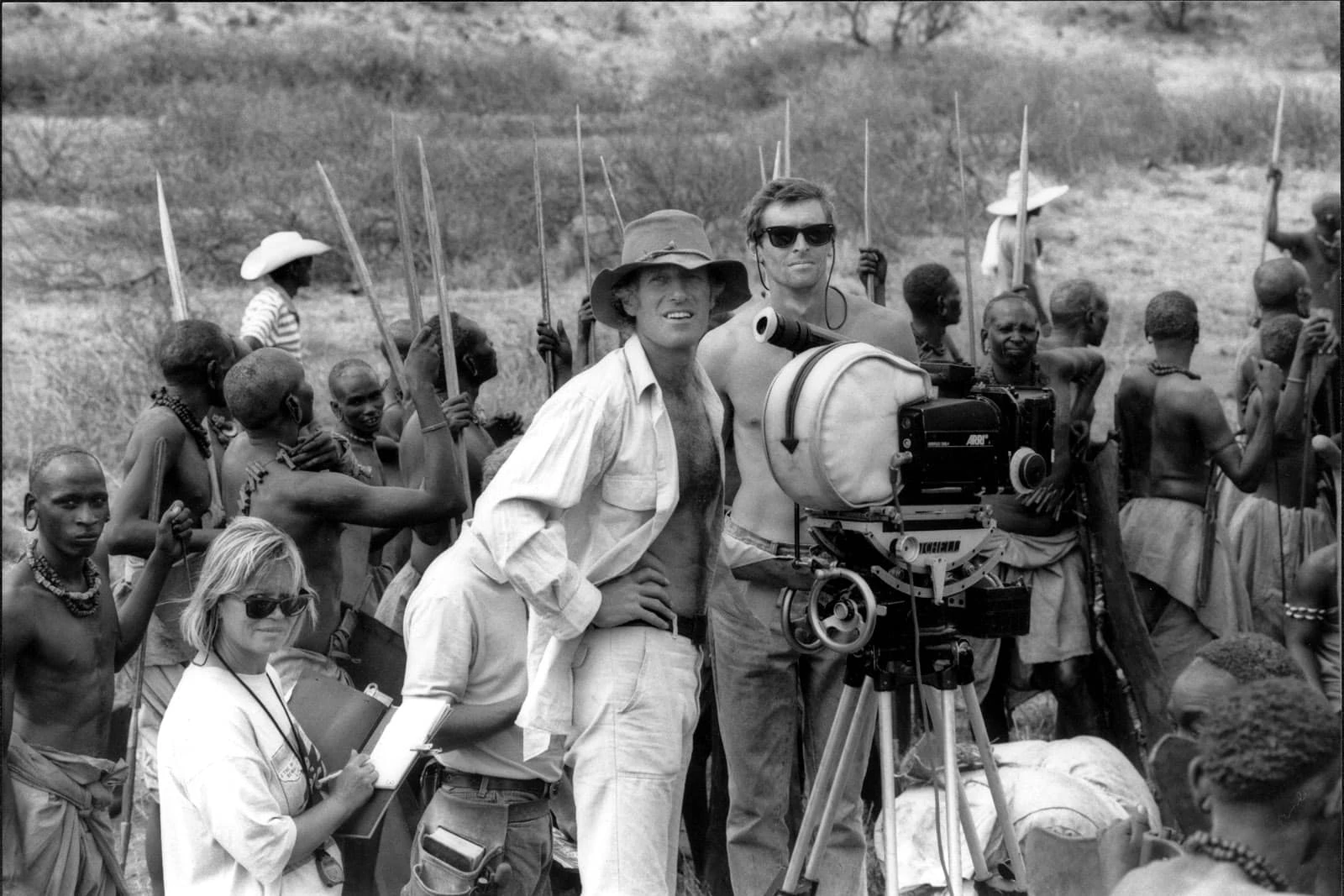

The anthropological documentaries Deakins went on to photograph taught him where to place himself and the camera and how to relate to a subject. It also gave him the opportunity to continue exploring the world. Shooting Eritrea – Behind Enemy Lines with photojournalist Sarah Errington saw him spend two months in Eastern Africa, depicting the conflict and Eritrea’s fight to gain independence from Ethiopia.

“I hadn’t travelled much so it was such a great experience to shoot a documentary in places nobody would normally visit unless they had special access. We travelled into Eritrea on the back of trucks supplying the guerrillas with food and medicine. That long drive from Sudan down the Red Sea coast into Eritrea made a lasting impression.

“It was fortunate I shot a few documentaries during a period when some TV producers were taking risks. We didn’t have a script or a front person, we just decided to make a film about a subject and went off to shoot it. You experience the situation and construct something from what you find and the people you meet, which is an interesting way to work. I kind of miss that form of filmmaking.”

Valuable lessons were also learnt shooting live music events and music promos and documentaries in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. “Those were crazy times. I was lucky with regards to some of the amazing musicians I filmed – B.B. King, Muddy Waters, and Chuck Berry, to name a few. When I filmed B.B. King he sat a few feet away with his guitar on stage and I had a 35mm camera on my shoulder. It was so riveting to watch. He then turned to me and said, ‘That camera must be pretty heavy. It’s probably heavier than my guitar.’ It’s all about special encounters with people such as that as much as anything.”

Whether it was shooting hard-hitting documentaries or concerts, those precious experiences informed Deakins how to read what was in front of him and allowed him to form lasting connections with fellow cinematographers such as Dick Pope BSC. “The people you work with become good friends. Back in the ‘70s Dick Pope, such a wonderful guy, would sometimes ask me to shoot second camera. One time he asked if I wanted to shoot a concert in Birmingham with him as they suddenly wanted another camera. Dick never mentioned who the band was but just to get to the venue as fast as I could. It was totally dark and quiet when I walked in, but I could tell there were thousands of people there. Up on the balcony, I found my way to the front to set up for a top shot of the band and suddenly the whole thing came to life as The Clash appeared on stage. Those special moments stick with you.”

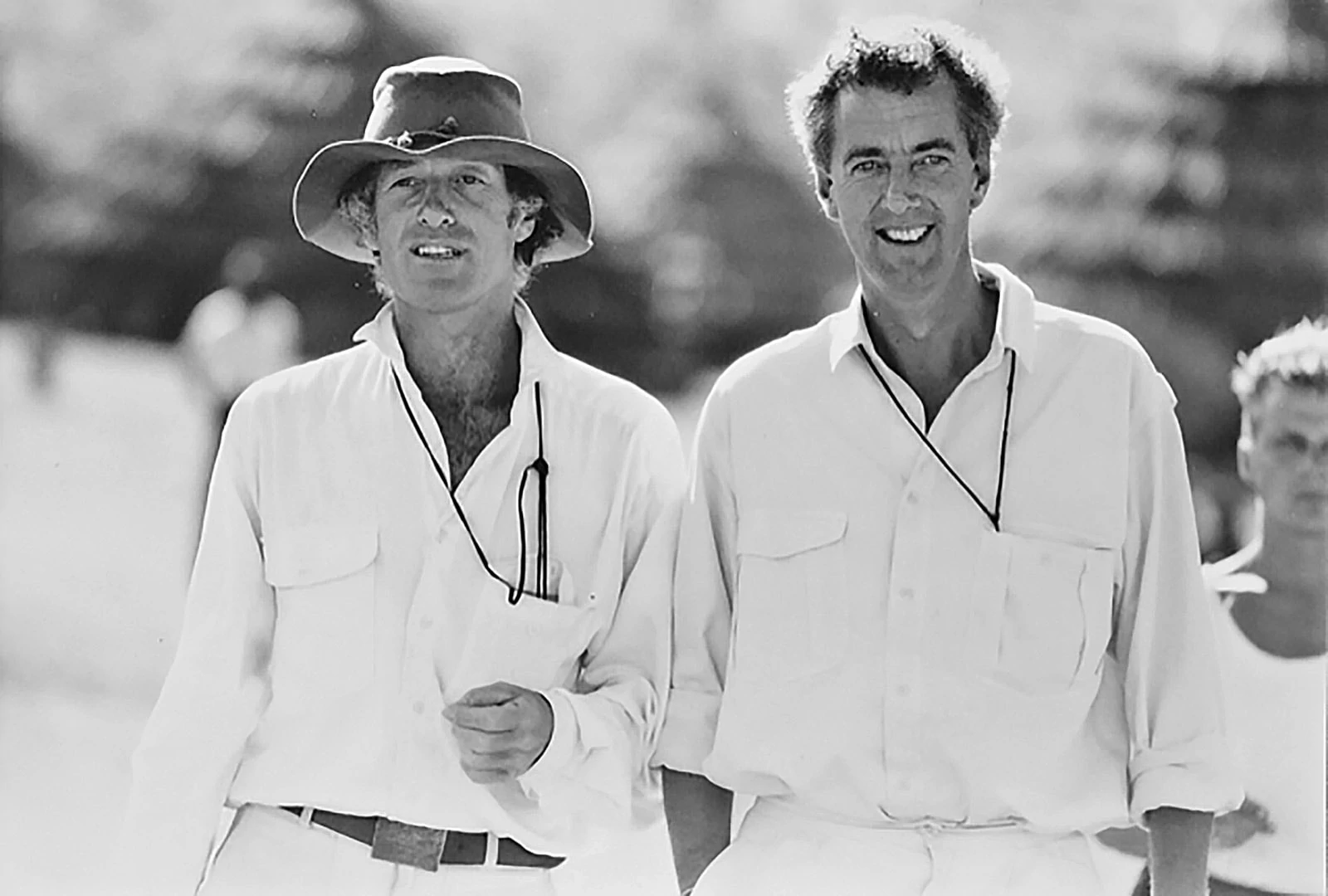

With a growing list of documentary and music-related film credits to his name, Deakins ventured into drama, shooting detective TV mini-series Wolcott (1981), which caught the eye of fellow NFTS graduate and former collaborator, director Michael Radford. “Mike asked me if I would like to shoot his first feature Another Time, Another Place and he later told me this was mainly because I had filmed that TV mini-series and had some experience of shooting drama.”

Having received critical acclaim for Another Time, Another Place (1983), when Radford went on to direct dystopian sci-fi 1984, he collaborated once again with Deakins, a pivotal point for the cinematographer which reinforced his desire to pursue a career in feature films. “When I started out, I thought I was going to shoot documentaries, but sometimes life leads you down a different path and you just hold on and enjoy the ride. You end up on the set of 1984 and sitting on the hillside on the edge of Salisbury Plain at lunchtime with John Hurt and Richard Burton talking about their film life and just thinking, ‘Oh, my God, how did I get here? Maybe this is what I’m meant to do.’”

I’ve only really successfully worked with directors who enjoy the fact I operate. I once tried to make a film and I wasn’t operating. It was very ineffective for me – I just couldn’t do it. Being with the camera and having that physical connection to create the image is really important to me.

Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC

A SHARED PASSION

Believing collaboration to be at the heart of the filmmaking process, Deakins cherishes the rewarding working relationships he has enjoyed, whether it be with inventive directors and skilful camera crews or talented gaffers and colour grading maestros.

And while every relationship he has formed with a director has been different, each one shared a similarity: “I’ve only really successfully worked with directors who enjoy the fact I operate. I once tried to make a film and I wasn’t operating. It was very ineffective for me – I just couldn’t do it. Being with the camera and having that physical connection to create the image is really important to me.”

From 1991 comedy drama Barton Fink through to 2016’s Hail, Caesar!, Deakins has lensed 12 of the diverse and iconic films directing duo Joel and Ethan Coen have made. “I first met them in Notting Hill in London when I had just finished Mountains of the Moon and Air America. We got on from the get-go and that didn’t change from the first film we made together. The more you work with people, the more mutual trust and understanding you develop,” he says. “I can read one of their scripts and immediately understand what they’re visualising. Obviously, I was nervous on Barton Fink because it was my first time shooting a studio picture in LA, but it didn’t feel hierarchical at all. I remember more than anything, the film was a fun collaboration and all the films I’ve made with them since have also been fun.”

Deakins admits he relishes the experience of working on disparate styles of film and helping create different worlds. “Chris Menges has always been my hero and I saw myself making more realist films on contemporary social subjects in a similar vein to him, both of us having come from documentary backgrounds. I then segued into working with Joel and Ethan for a long period and discovered you don’t have to make films about contemporary life to explore contemporary issues or connect with an audience. You also don’t have to set them in today’s world which opens up all sorts of possibilities.”

Making Blade Runner 2049 (2017) with director Denis Villeneuve was one example. “I was surprised by how much I loved making it. I like science fiction, but I really enjoyed creating that fantasy world which is based on reality. One of my favourite films is Andrei Tarkovsky’s sci-fi Solaris because there’s something so immersive and emotionally connecting about it. I would like to do more science fiction, exploring serious sci-fi rather than fantasy.”

Having collaborated with some of the finest directing talents, has Deakins considered exploring directing himself? “I’ve written a couple of scripts and toyed with directing, but spending a few years waiting to get a project together is not really me. I’m better suited to helping somebody else. I’m not very confident so the thought of trying to sell myself in meetings just isn’t me. You have to accept your strengths and weaknesses, and I’ve been lucky to find this niche for myself and to have worked with wonderful people.”

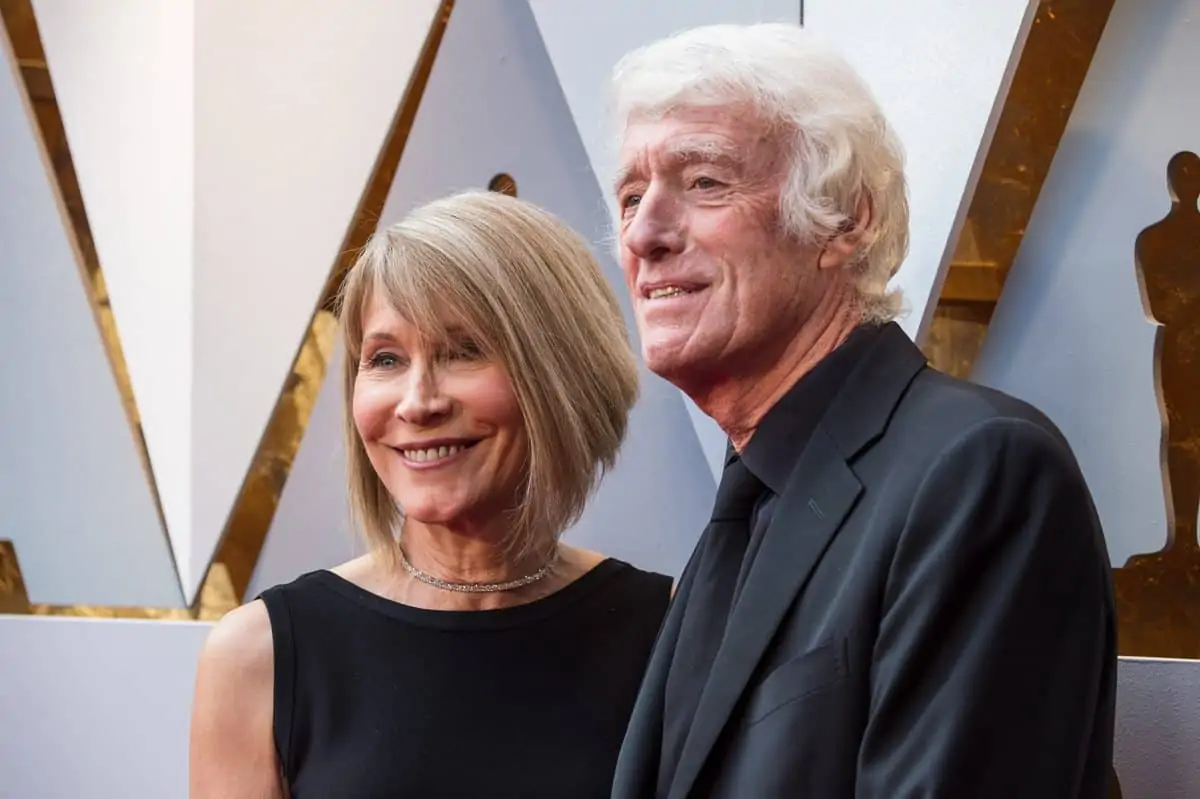

One of Deakins’ other key collaborators is his wife James Deakins. With technical expertise and a shared passion for the art of filmmaking, their skillsets align perfectly. After meeting on the set of Thunderheart in 1991, which James was script supervising, their working relationship evolved on various subsequent productions.

“We thought it made sense for us to continue collaborating, with James overseeing the digital workflow. When I operate it’s great to know she is handling the production issues, especially in the digital world and with the effects work, it becomes a complicated process. She coordinates that so I can concentrate on being on the set and relating to the director or actors. James is incredibly technical and is probably a better people person than I am. We work really closely and talk about the visual approach, not just technical analysis.”

Valuing the crew behind every production, Deakins has assembled a team he has reunited with multiple times over the years to create cinematic splendour. Members of that trusted filmmaking family include gaffer John “Biggles” Higgins, gaffer Billy O’Leary, key grip Mitch Lillian, colourist Mitch Paulson, and 1st AC Andy Harris, all of whom have enjoyed successful production partnerships with the cinematographer.

“You feel more confident when you’re working with friends – not just because of their ability. You know they’ve got your back, that you have similar sensibilities and you both have a passion for the job. There’s that reassurance that I can go on a set and know that familiar person is there,” he says.

“For instance, Biggles did such a wonderful pre-rig and pre-light for a Genesis music promo we worked on in 1983 – so perfect and neat – and we became friends from then on. When I was preparing to shoot 1984 I asked if he wanted to be the gaffer. We had such a great time and learnt together, and it’s been like that ever since. On Skyfall we spent many weeks researching the latest developments in LED screens and on 1917 we researched all sorts of bulbs and remote dimming systems.”

In the US, Deakins has worked for more than 30 years with the same focus puller, Andy Harris. “It’s not just because he’s an unbelievable focus puller, he’s also a really good guy. You meet up on the next movie and you’re surrounded by friends – it’s a comforting feeling. If I meet somebody for the first time and we get on, I like to keep that connection. I usually find the passion someone has for the job is as important, if not more so, than experience. You can learn technique and technology, but you can’t learn passion.”

The on-set relationship with actors is also essential for Deakins. He believes it is part of the cinematographer’s and crew’s role to create an atmosphere the actor feels confident to work in. “Often they’re letting out something very personal and they have to feel secure in that environment to do so. You also try to create a space for directors where they can have that time with the actors.”

That ability to collaborate and share wisdom has also seen Roger and James Deakins take on the roles of visual consultants to advise the likes of Pixar, Dreamworks and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) while creating magical worlds in animated features such as Wall-E (2008), How to Train Your Dragon (2010) and Rango (2011). “Director Andrew Stanton wanted Wall-E to feel very like live action in the sense of where the camera moved, and how cuts were made. When we worked with Gore Verbinski on Rango, we mainly liaised with ILM about lighting. Again, I loved the collaboration between a big group, all working together with a shared goal and passion. And I enjoy that process of using images, movement, framing, and lighting to help tell a story.”

LIGHTING THE WAY

Developing a cinematographic style is in part down to practice but also “just looking at what you like and dislike,” according to Deakins. “Sometimes I don’t like the way a film looks, its pacing, or the choice of lenses. That’s valuable because you find out what you like – and then you aim to work with directors with a similar view.”

Keen to get involved early and spend a long time in preproduction, Deakins usually requests to be on the initial scouts to “understand what the director is thinking” and feel his way into a project. On Skyfall (2012) and 1917 (2019) Deakins and director Sam Mendes spent months discussing the script, what the environment should be, how to move the camera, and location scouting. “During prep for 1917, we went to France to look at some existing trench lines from World War One. That experience was not just about what we were looking at, it was about talking to each other about what we were seeing and using that to start creative conversations.”

As they did on Sicario (2015) and Prisoners (2013), Deakins and director Denis Villeneuve enjoyed an extensive location scouting and prep period for Blade Runner 2049, examining the architecture in places such as The Barbican and the National Theatre on the South Bank in London. “It was a way of looking at things together and understanding the world we wanted to create, so we could gradually focus in on a particular look. I also love spending time talking through storyboards with directors. We may throw them away later, but it’s a great way to learn the specifics of a scene.”

As much as Deakins is a fan of prep and in-depth discussions with directors, he is also open to making new discoveries on the day. “You should never feel you’re just reproducing what you’ve drawn on the page or the production designer has painted as a reference. You go into a shoot being open to anything, whether it’s an idea the director has or the way the light hits something on the day.”

The master of illumination sees lighting – an essential tool in every cinematographer’s arsenal – as “instinctive”. “There was a night scene in No Country for Old Men that Joel and Ethan had storyboarded as a number of shots and then on the night of the shoot I suggested we play it as a profile silhouette. Sometimes something comes instinctively, and you realise you don’t need to see the two characters’ faces at that moment. There was something about seeing them in the space as silhouettes that worked and then at the end of the scene we went to a close-up as that was the moment Joel felt we had to see an actor’s face.”

If the audience ever start seeing the technology, you’ve made a big mistake. You want to immerse them in the story, not show off with the way a shot is lit or the way the camera has moved. The technology you use should be invisible, just part of the experience.

Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC

THE STORY COMES FIRST

A seasoned cinematographer such as Deakins with a filmography of epic proportions can still feel nervous before a production. “Sometimes when I start on a film, I feel it’s almost like I’ve never done it before, and I sort of have to relearn,” he reveals. “I’m anxious about going on a film set after the pandemic because I haven’t picked up a film camera for about 18 months. I’m terrified, but I always am when I first go on set.”

From creative quandaries and technical complications through to difficult-to-light locations, he has overcome a multitude of challenges. Sometimes the smaller films present the biggest obstacles such as the wintry nighttime car chase in the Coens’ indie comedy thriller Fargo (1996) which was testing, partly due to the lack of required snow.

“And then there are the technical challenges. We wanted to make 1917 look like it was all one shot which is great, but it also demanded a lot of prep, working with Steadicam operator Pete Cavaciuti and Trinity camera operator Charlie Rizek to find ways of moving the camera and shifting from one mode of operating to another.”

When shooting certain demanding night scenes in No Country for Old Men (2007) he had to convince production that two Musco lights – which are used to illuminate stadia – were necessary for a large night scene and then work out where they could be placed out of shot. “You’re not only trying to imagine the look in your head. There’s also the logistical challenge of how the devil you get the lighting in the place to create that look. That’s the fun of it though – it’s a wonderful combination of creative discovery and technical challenge.”

But storytelling and creativity always takes precedence over technology. “If the audience ever start seeing the technology, you’ve made a big mistake. You want to immerse them in the story, not show off with the way a shot is lit or the way the camera has moved. The technology you use should be invisible, just part of the experience,” he says.

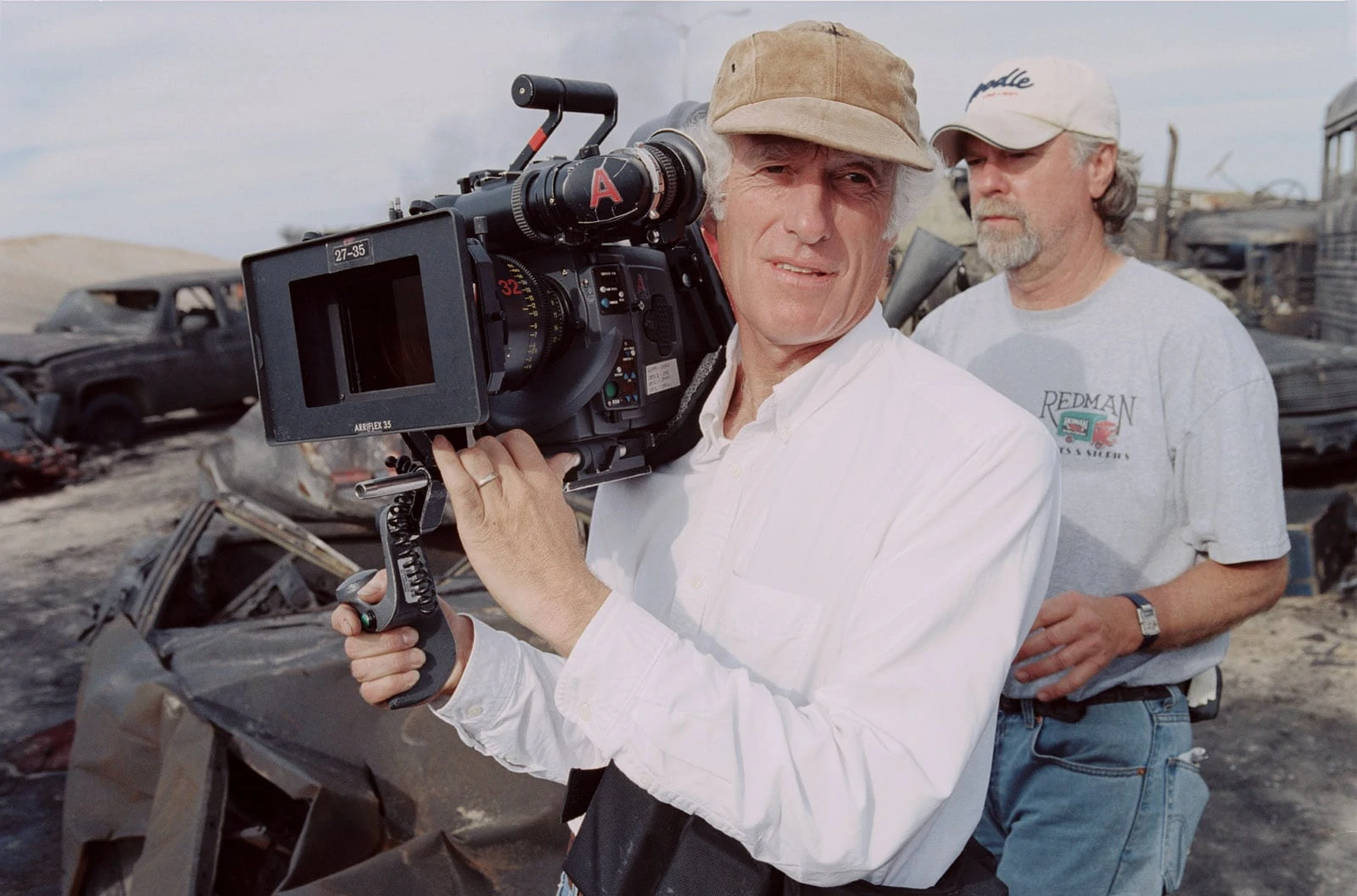

Enjoying shooting handheld, Deakins looks for a camera that ergonomically fits on his shoulder and works efficiently on a head when remote operating. “I’m quite straightforward in terms of the camera I like. I’ve always used ARRI’s Arriflex in the past and now the Alexa. ARRI even developed the Alexa Mini LF quicker than planned because they knew we wanted to shoot 1917 with a large format camera that was more compact.

“The team at ARRI were brilliant throughout that process. I remember we were at the rental house picking up the little box – so delicate and precious – that contained the LF body. It was a wonderful moment. We were so excited, but I was scared to take it out because I didn’t want to damage it, so we did the tests on a standard Alexa to avoid putting the Mini LF body on a rig.”

Liking to create an image that reflects what he sees with his eyes, Deakins rarely uses old lenses or filtration. Once he has found a set of lenses that he feels is the “cleanest, sharpest, most lightweight and fastest” he sticks with it. He seldom changes lens sets and normally only has one set on a shoot rather than multiple types.

One innovation he singles out as being particularly significant is the remote head. “I love looking through the camera, but I also enjoy the technique when you’re on a remote head and have the flexibility, when working with a dolly grip, of adjusting your shot quickly. It’s like a little dance we can do with the actors. Obviously, the stabilised systems we used on 1917 are also a huge advance. I also love what you can do in a DI but I don’t use it that much because I enjoy doing things in camera and I think the results are better when you do that. The exception was O Brother, Where Art Thou? back in 2000 which was hugely reliant on what we could do digitally. I still enjoy having that possibility, though.”

Impressed by the advances in CGI, Deakins also feels visual effects can be overused. “When you need to extend a set or just open up the scale of a film without spending millions, it’s a great tool,” he says. “I’ve had great experiences with directors such as Sam and Denis who want to do as much as possible in camera and I have steered away from movies with lots of green screen or LED backgrounds. I love being on a set and having a physical environment I can relate to.”

Being on a film set is the nearest thing to socialism because it’s all these incredible people grouped together for a common cause and that feeling is amazing.

Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC

INSIGHT AND ACHIEVEMENT

Having encountered all manner of production scenarios, Deakins is keen to share his insight and experiences, whether it be at Q&A gatherings or through RogerDeakins.com, the website he set up with his wife James in 2005and which has become a valuable resource for filmmakers at all stages of their career.

“We were speaking at a number of events and people would often come up to us after to ask questions because they were too nervous to ask in public. One day James said, ‘Why don’t we launch a website so people can ask these questions, and you can answer them all at once?’ We then started sharing diagrams to explain how we approached scenes which we still do to this day.”

The success of the website naturally spawned another fascinating source of information and inspiration, the Team Deakins podcast, which the pair launched last April and have been recording in their home in Los Angeles. Evolving with each episode, the podcast now not only features Roger and James Deakins speaking with their collaborators and those they admire; their guests also ask the Deakins to share their on-set memories.

“The podcast was another of James’s ideas – it all came from the concept of the website and how to connect people with the possibilities. Initially we were going to talk to people we work with about how they got into the business and how they approach the job. That expanded and now we’ve talked to more than 100 people. It’s fantastic and has been especially great during the pandemic and lockdown. We all got into the business in such different ways and we all have our own personalities and ways of working which I find fascinating.”

Deakins’ own enthralling career path has seen him admitted to the British Society of Cinematographers and American Society of Cinematographers, experiences he has found incredibly rewarding. “It’s just great to feel part of that community,” he says. “Cinematographers are so welcoming and enjoy swapping ideas and being open about what they do.”

The icon of cinematography has received five BAFTA Awards for Best Cinematography, 15 nominations and two Academy Award wins for Best Cinematography (Blade Runner 2049 and 1917), five ASC Awards and seven BSC Awards for Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Release. But which achievement is Deakins most proud of? “It’s very nice to be nominated or to win awards, but I’m most proud of just shooting the films – it’s what I love. Receiving Oscar nominations and not winning was really fun but then winning the awards was really fun as well. But many of the films I think are most beautifully shot have received no such acclaim. So, awards are very nice, but you’ve also just got to see it as being very lucky. You’re in a particular moment and the film has reached an audience.”

Having been the first cinematographer to receive a CBE in 2013, Deakins was “flabbergasted” to hear he would be knighted in the 2021 Queen’s New Year Honours for his exceptional contribution to film. “The first thing I thought was, ‘If anybody should have had a knighthood in my family, it should have been my dad because of his experiences in the war’. I didn’t do anything in comparison – he really deserved it. But it is lovely that cinematography is being recognised. It is also all down to a combination of not only the directors and the actors I’ve collaborated with, but the crews I’ve worked with. It’s John Higgins, Billy O’Leary, Mitch, Bruce, Gary, Andy, Peter, Charlie, Josh, Malcolm and the list goes on. It’s all those special people, not just me.

“Being on a film set is the nearest thing to socialism because it’s all these incredible people grouped together for a common cause and that feeling is amazing. Sometimes you have to pinch yourself when you’re on set to remind yourself how lucky you are.”

EXCLUSIVE SIR ROGER DEAKINS MASTERCLASS

You can read even more insight from the legendary Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC in an exclusive Masterclass article written for British Cinematographer Issue 104 by purchasing a Digital or Print & Digital subscription to our magazine.

From intricate illuminations through to ambitious camera movements, Sir Roger shares insights into the creation of scenes from a selection of films he lensed including Oscar-winning 1917 and Blade Runner 2049, along with lighting diagrams, sketches, and location photos.

To read this exclusive article, simply purchase a Digital or Print & Digital subscription today by clicking the button below…

CONGRATULATIONS,

SIR ROGER!

A selection of Roger Deakins’ collaborators and fellow filmmakers and film-lovers highlight the impact his work has had on them, share their experiences of working with the cinematographer along with words of congratulation.

“Sir Roger has always been my knight in shining armour – and now it’s official. Working so closely with Roger is beyond amazing. He is a true collaborator as anyone who has ever worked with him knows.

We both are very passionate about filmmaking and it’s wonderful to share that 24/7. Being around his “eye” for so, so many years has enlarged my vision and I love it. But it’s not just his talent that awes me, it’s also his honesty, generosity and genuine collaborative spirit. Congratulations, Sir Roger!”

James Ellis Deakins, Team Deakins

“Roger Deakins has had the highest influence on me, as an artist and as a human being. He is a true mentor. His humility, his artistic integrity and his dedication to perfectionism are one of a kind and absolutely remarkable.

He is, in the most romantic way, an artist, his life being entirely devoted to cinema. I don’t think he likes to hear that he’s become a legend, his modesty being legendary as well. Indeed, Roger is one of the great masters of filmmaking history. And as all the great masters, he only listens to his muses.”

Denis Villeneuve

“For Roger. With deep admiration and gratitude for your magic eye and superb skills. And to the wisdom of your teachers and for the passion you have brought to the cinema. Bless you.”

Chris Menges BSC ASC

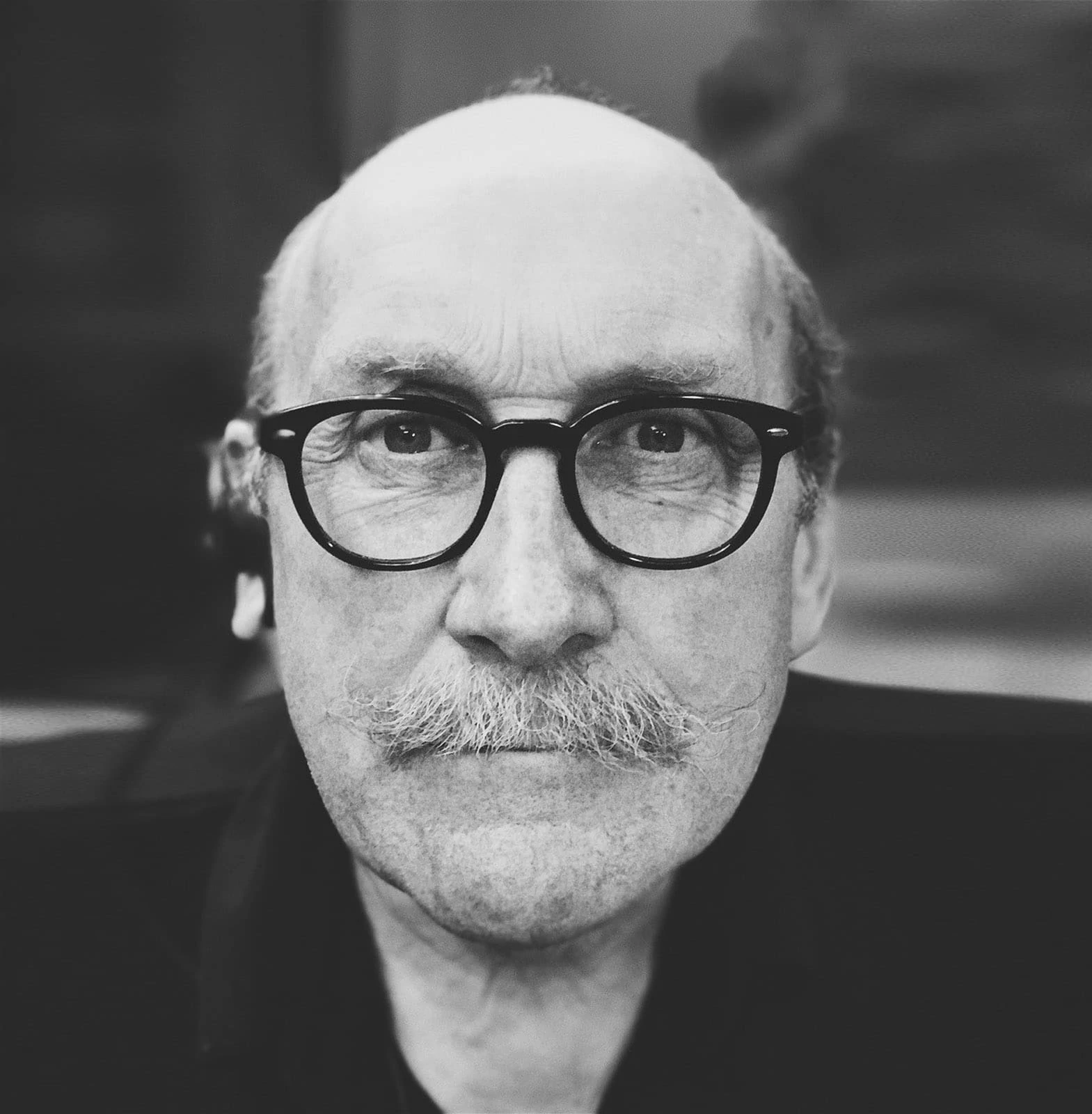

“I first started working with Roger back in 2010, on the film True Grit. We’ve coloured nine movies together since then. Every time I work with him, he makes me a better colourist. I don’t think I would see colour the way I do, had it not been for working with him so many times.

I learn something new on every film we do together. He is truly a master of his craft and I am very fortunate to have worked with him so many times. One of the most memorable times was when I travelled to London, to colour Skyfall with him and James. It was a trip I’ll never forget! Congratulations on your knighthood Roger!”

Mitch Paulson, supervising digital colourist, Company 3

“Sir Roger Deakins has been a friend and beacon to cinematographers worldwide for as long as I can remember. His humility and willingness to share his expertise with his colleagues and students is legendary. No two films photographed alike, yet each exceptionally lensed, Deakin’s body of work sets the benchmark for all who aspire to outstanding visual storytelling.

It’s one thing to be the perpetual Oscar nominee, it’s a whole other stratosphere when you’re royalty. Congratulations Sir Roger! Proud to have a Knight as a friend!”

Rachel Morrison ASC

“I want to congratulate Sir Roger Deakins on this fitting recognition of his extraordinary skill as a cinematographer. What a pleasure it has been to work with him over so many years. From our first film together 1984 to the latest 1917, it’s been a great collaboration, even though he still supports Manchester United. You can’t win them all!

Unlike his choice of football teams, his vision, talent, and creativity as a cinematographer just can’t be challenged. I have learned so much from him through the years. Here’s to many more unforgettable films.”

John “Biggles” Higgins, gaffer

“Roger Deakins is a masterful cinematographer. I began working at Deluxe Laboratories, Los Angeles in 1993. Roger was a client and from watching his dailies I realised that Roger Deakins was one of the best and had been for a while. He shot one of my favourite films Sid and Nancy. From watching it, I could see that Roger was “Roger” then. He was not becoming one of the best cinematographers in the world, he already was and had been since putting his eye to an eye piece.

My favourite collaborations with Roger were The Man Who Wasn’t There and The Assassination of Jesses James by the Coward Robert Ford. Even now when I watch them, they stir so much emotion in me because of their beauty and texture. Congratulations, Sir Roger!”

Beverly J. Wood, former Executive VP of Technical Services, Deluxe Entertainment and managing director, EFILM

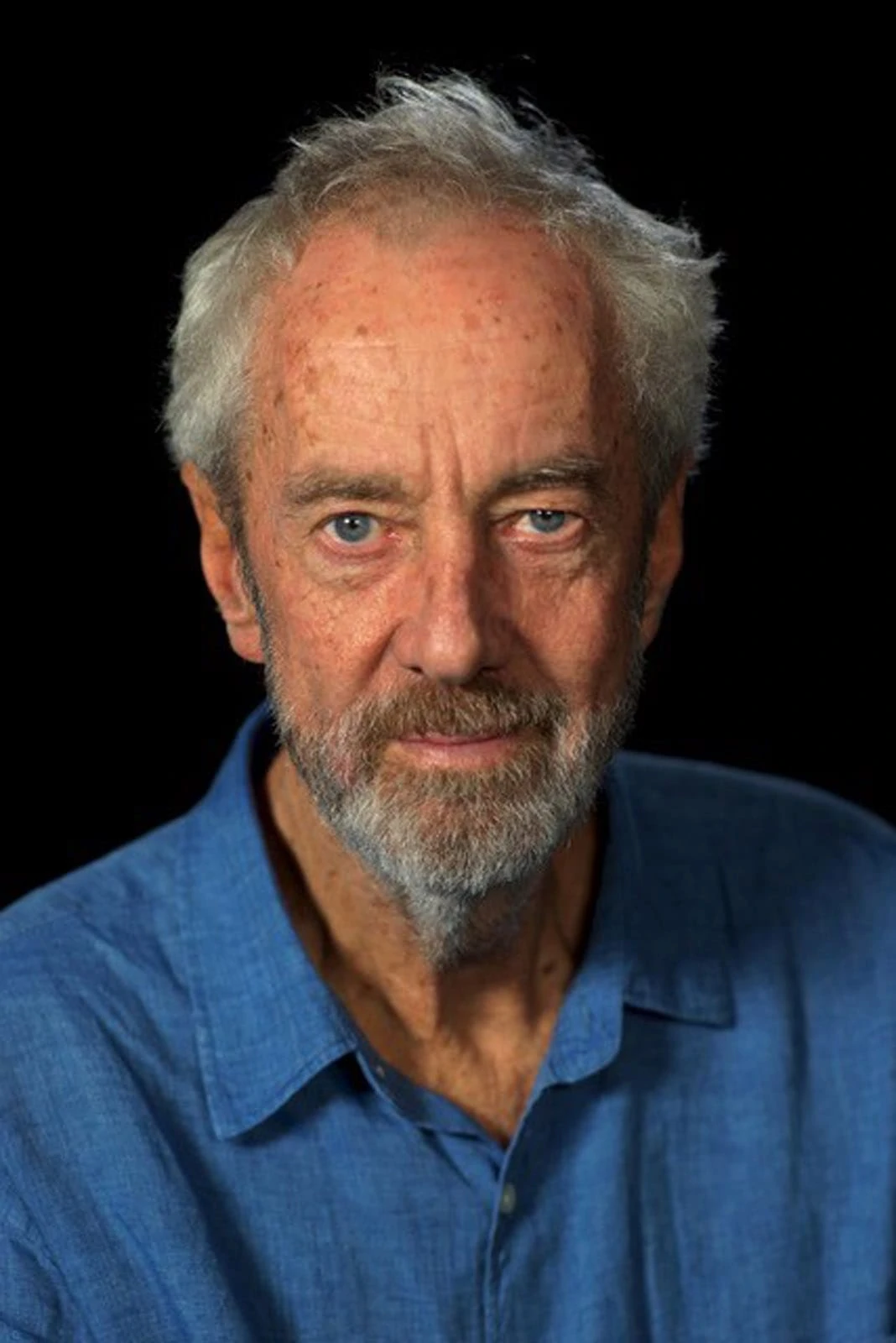

“I made my first three films with Roger Deakins – Another Time, Another Place, 1984 and White Mischief. We always collaborated very well and indeed went to film school together even though my passion was European Cinema and Roger wanted to go to Hollywood. I thoroughly and completely enjoyed working with this supreme talent. His patience and his thoughtfulness were unlike anything I’d experienced before with a DP – one who had an incredible vision of things. He could turn something I said into light, interpreting exactly what I had envisioned.

I am delighted for him that he has been recognised for the brilliant talent that he is. Congratulations Sir Roger Deakins on this well-deserved accolade. I sincerely hope we get to make at least another three films together.”

Michael Radford

“Sir Roger Deakins’ filmmaking roots were cultivated here at the NFTS and we are so proud of his many exceptional achievements. Sir Roger has become a true master of the cinematography profession and his ground-breaking contribution to film and culture is unmatched.

At the NFTS it is our mission to shape the next generation of filmmakers and Sir Roger is a shining example of what can be accomplished by sheer hard work, determination, and boundless talent. We are incredibly grateful for his on-going support of the School and the invaluable encouragement and advice he regularly gives our current students and alumni. I’d like to say a huge thank you for bringing to life so many incredible films that will live long in the memory and we all eagerly await the opportunity to consume, dissect and learn from his next project!”

Jon Wardle, Director of the National Film and Television School (NFTS)

“Roger Deakins is unarguably the most, talented and naturally gifted cinematographer working in the world today, as his work testifies on every outing. Many years ago, his career shot into the stratosphere and of course remains up there to this day. Suffice to say he has photographed some of the most indelible images on many of the finest films over the past 35 years, proving himself over and over to be one of the greatest DPs, if not the greatest of all time. Every film he shoots heralds a much-anticipated major cinematographic event, but he’s never had his head in the clouds and has always remained down to earth and wonderfully grounded.

Roger gives back so much and for young and aspiring film makers he has become an idol, always approachable and incredibly giving with his time and thought processes. He is always willing to give advice to anyone who asks, and I for one have asked often. He also makes the time to run his and James’s fantastic website. This brilliant forum is a magnet for all, young or not so young, starting out or established, always with great discussions and answers from him that are truthful, pragmatic and honest. This of course has now been joined by their ever so popular Team Deakins podcast, now with an online following of more than two million! I’m so proud of his achievements and to be able to call him a friend.”

Dick Pope BSC

“Roger’s work over the last thirty-five years or so has represented not only high-water marks in cinematography but also cinema itself. This is no coincidence. His care and control toward the art and craft represents storytelling at its most deceptively simple. He often reminds me of the best kind of writer who ignores unnecessary flourishes and pyrotechnics and knows that economy and preciseness is the best possible way to communicate an idea. The inherent ‘truth’ in his approach while serving character, environment and narrative is something all students of cinematography should study and take note of.”

Mike Eley BSC, BSC President

“Roger Jolly Rodger. Born by the sea and still living by the water across the great pond. The wind is still in your sails after 30 years, an apparent journey of extraordinarily few complications.

I came to know your eyes before I found my own. I hit the street following the late 1984 screening, hypnotised by your images which hammered home to me the simple truth that art and narrative cinema can and should bleed through the cinema screen just as any painting can. This galvanised my faith to find my own life with the moving image.

Time passes. ‘One Camera Deakins’ or ‘Less is More’ Roger are often quilled as important attributes or indicators to your craft. I could not disagree more with such war cries and anthems of this kind whilst in the same breath, I continue to acknowledge in awe, the tantalising beauty and precision you vividly render through pixels and celluloid alike. Action speaks louder than words.

Brandishing your admiral hairstyle. I met you for the first time in 2009 in a Santa Monica pub that resembled a ships galley. The humble man who gave me my eyes became a friend in the flesh and is now a knight to his land and country.

I don’t mind if you ride a white horse side saddle to work from now on. Myself and many others will continue to watch and learn from you. Maybe one day soon we’ll have a celebratory noble pint! Congratulations team.”

Anthony Dod Mantle ASC BSC DFF

“Congratulations to Sir Roger Deakins on his knighthood. A recognition so greatly deserved. I have been so very fortunate to work with and be a part of so many amazing, ground-breaking, award-winning cinematic projects with Roger over the past 30 years. To be able to witness his talent and vision up close on a day-to-day basis is an experience that I would have never imagined, and that I will cherish forever. There are so many incredible memories!

As far as the knighthood goes, I’d like to quote a good friend of ours, Bruce Hamme (Roger’s dolly grip for many years). ‘It’s ironic for the guy who always disliked being called Sir on set (he said it made him feel old) that now he will not be able to escape it.’”

Andy Harris, 1st AC

“It’s often said you should never meet your heroes, let alone spend six intensive months working on a ground-breaking and extremely challenging film. 1917 is a very special film in so many ways and for all the right reasons. Roger’s wholesome devotion, determination, sensibility, attention to detail, approach, methodology and preparation is totally addictive and leaves no other choice but to give all you can, all day every day.

Being great leaves no stone unturned. Filmmaking is a collaboration. Choosing the right crew for the job has obvious importance but even more vital is the ability to establish relationships based on trust to bring the most out of people around you.

It was my absolute privilege to work and learn from you. Having you as a mentor and a friend is an honour that I will cherish for the rest of my life. Lest not forget behind every Sir there’s a great Lady. Congratulations to Sir Roger and Lady James on the richly deserved knighthood. Here’s to the next decade of masterful, inspiring, and moving films.”

Charlie Rizek, camera operator