FRIGHT CLUB

Tasked with reviving the legend of a demonic serial killer terrorising smalltown Louisiana, cinematographer Simon Rowling wasn’t spooked by the challenge ahead.

“Jeepers creepers! Where’d ya get those peepers?”

It’s a tune that makes a generation of horror fans shiver; the blood-curdling calling card of the Creeper, who stirs for 23 days every 23 years to feast on human prey. He comes out of hibernation this autumn as Jeepers Creepers: Reborn slithers into cinemas, following in the fearsome footsteps of Candyman and Scream as the latest spooky reboot.

The series’ fourth instalment follows young couple Chase (Imran Adams) and Laine (Sydney Craven) as they visit Louisiana’s Horror Hound Festival where, in true-to-genre style, sinister antics ensue. Just three days of filming took place in the Pelican State before the production moved to the UK, pitching up at Hampshire’s Black Hangar Studios.

“It was freezing cold – it was December, and we were shooting on a British airfield, so the wind chill was about -10 °C,” remembers DP Simon Rowling with a smile. “It was supposed to be spring in Louisiana, but you could see everyone’s breath!”

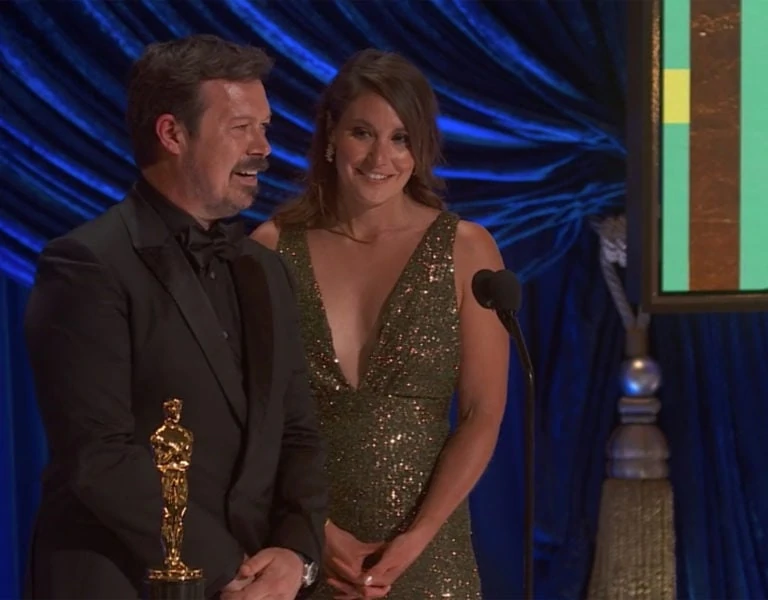

Rowling joined Jeepers in late 2020 after a short he had lensed (the Oscar-longlisted Cognition) caught the producers’ attention. The production promised a set of new challenges for the cinematographer: he’d have to get to grips with big set builds, do lots of green screen and live virtual environment work, and withstand the pressure of shooting a franchise film for the first time. No mean feats against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Early conversations with director Timo Vuorensola – also new to the franchise – centred on the film’s look. Among the pair’s cinematic references for the lighting and colour palette were Se7en, the IT reboot and Don’t Breathe. Interestingly, Rowling didn’t rewatch or reference any of the previous Jeepers films, instead wanting to start afresh. “We wanted to give a slick, modern, glossy look to an old franchise” he adds.

To help give it that sheen, he chose the ARRI Alexa Mini LF with Zeiss Supreme Prime Radiance lenses, mostly shooting at T2 or T2.8. “The full-frame sensor meant I could shoot on wider lenses but keep the shallow depth I wanted because there were always two to five people in every shot,” he explains. The RED Komodo was also used for a POV shot of the Creeper as well as for dream sequences, along with a Lensbaby.

Rowling’s team included gaffer Sonny Horwell and 1st ACs Hermes Contreras and Rupert Peddle, and B-cam and Steadicam operator Robert Beck ACO. “Sometimes [with Beck] we would shoot back-to-back and then swing around to keep the scenes rolling and get as much as we could, as there are lots of scenes with a lot of the cast, which meant vast amount of coverage,” the cinematographer recalls.

Shooting the big set-builds, like the Creeper’s lair, was a highlight for Rowling. But given their size (19m wide by 16m long, with almost 3m high walls), lighting proved difficult. The DP used various HMIs placed around the outside of the set to act as moonlight. The lights streamed through the boarded-up windows to give the set some shape.

“We also just smashed holes through the set walls and drilled holes everywhere, so we had this hard moonlight punching through them. Anywhere I could get light into the set I would, and we didn’t mind destroying the set to do so!” he adds.

For soft lighting inside the set and for close-ups, LiteMats were used on stands and Astera Titan tubes screwed into the wooden set. For a base level of light throughout the set Rowling had around 30 SkyPanels scattered around above the rooms, all with custom egg crates.

Innovation was key when it came to the set’s ceilings, which were covered by large moveable canvas frames. “We had one long corridor shot where the actors are running, which is on the first floor of the building. We see the ceiling the whole time – so if we had SkyPanels there and no ceiling, you’d see them all. I wanted the actors to always move through pools of light throughout the building, so I sliced holes in the canvas ceiling as though the creature had been clawing away at it. This worked so well that we ended up doing this throughout the entire set,” Rowling explains.

The physical sets were complemented by a series of virtual environments – the hotel, graveyard, shop and attic – where real props were used along with CG walls and floors, shot using the Mo-Sys tracking system. For the attic set, Rowling worked closely with the virtual effects company to pull off the lighting needed. “I discussed with them how I wanted the light to play in the virtual world, with the roof’s splintered wood cutting the shape of the moonlight. But we needed to replicate this on the green screen set. So, using large sheets of Correx, we cut out splinter shapes, then put HMIs behind them, creating our own large cucoloris. This would provide us with the shafts of moonlight needed to match the VFX environment and light interaction on the actors’ faces.”

Rowling admits the production had its amazing highs, but as is sometimes the way, its lows too. “As a DP, after I hand over the footage I have to accept that due to the nature of some productions, I might inevitably lose control of the image and what happens to it in post,” he says. “One can only do their best on set to implement as much during the filming process as possible, such as using LUTs and making notes for the VFX team and to try and push for things to be shot in-camera. Ultimately though, as much as we strive to have control throughout a project as a DP, unfortunately, sometimes it is not possible.”