COSMIC CREATION

Robert Yeoman ASC enjoyed another inspiring creative adventure with director Wes Anderson, exploring new filmmaking terrain to create a multi-dimensional story that plays out in a stunning pastel coloured dreamlike desert and the contrasting harshly lit black-and-white world of a television studio.

As expected from a Wes Anderson creation, the immersive and distinctive narrative and cinematographic style of his latest venture transports the audience to a visually spectacular world of wonder. This time most of the story unfolds in the American Southwest in 1955 – with the aftereffects of World War II still lingering – as we are introduced to Asteroid City, a desert town that is home to a population of 87 with a nearby US government observatory and giant crater where millions of years ago a meteorite landed.

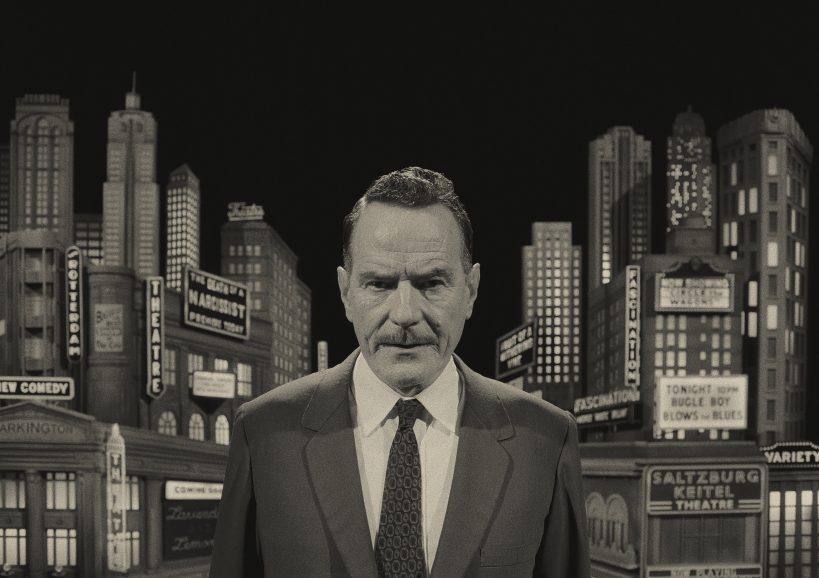

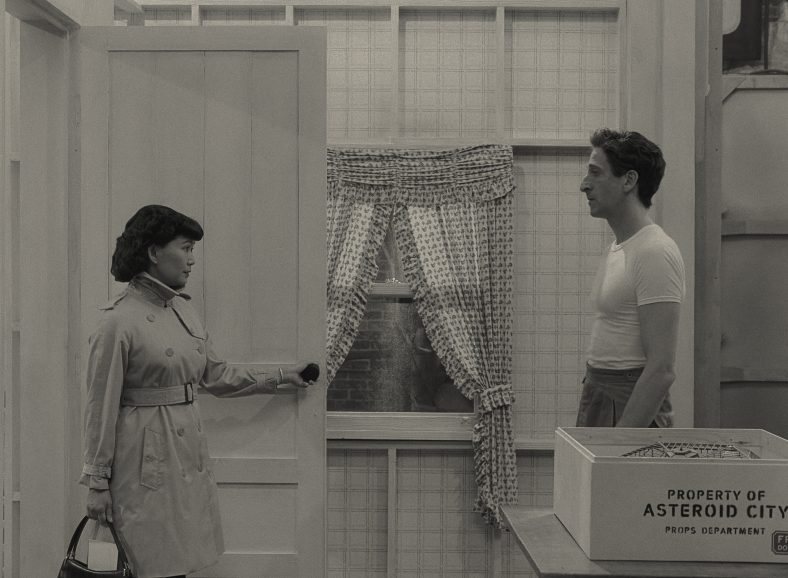

Part of the action plays out in black-and-white on a studio set resembling shows such as Playhouse 90 from the 1950s Golden Age of television – a period that “was the centre of everything” for Anderson when his passion for moviemaking began. In the play-within-a-play he weaves into the narrative we meet Bryan Cranston’s character – host of a TV show presenting a three-act stage show featuring Jones Hall (Jason Schwartzman) and Mercedes Ford (Scarlett Johansson) as the leads acting out the play Asteroid City alongside other performers.

“You’re ultimately seeing an actress playing an actress playing an actress,” explains Anderson, who believes a movie is not just a single idea, “it’s at least two separate things that come together and start to become a movie.”

The first idea conceived by Anderson and Roman Coppola – who co-wrote the story for Asteroid City – began in the east metropolis, but soon pointed elsewhere. “I wanted to do a theatre movie… and we had an idea of doing a making-of-the-play that they’re working on… we were calling it “Automat”, and it was going to be set entirely in an automat [a fast-food restaurant where simple food and drink is served by vending machines],” says Anderson. “The other thing we were talking about was something kind of Sam Shepard. So, we shifted out of “Automat” and into the desert.”

The result is a multi-faceted tale that explores the mysteries of the universe while depicting its characters’ experiences of a myriad of emotions from grief through to paranoia. As the 1.37:1 black-and-white world of the TV studio expands to widescreen colour, the audience begins an adventure on top of a freight train headed into Asteroid City, which as host Cranston highlights “does not exist.” It is an imaginary drama created for the broadcast, complete with fictional characters, hypothetical text, and events that are “an apocryphal fabrication – but together they present an authentic account of the inner-workings of a modern theatrical production.”

Anderson’s idea to shoot the sequences in the TV studio in black-and-white and a 1.37:1 format, and the world of Asteroid City in anamorphic and glorious colour was the first thing he discussed with cinematographer Robert Yeoman ASC who has collaborated with Anderson since the director’s first film Bottle Rocket in 1996.

Some members of the ensemble cast appear in the black-and-white world and in the colourful Asteroid City such as Schwartzman who plays war photographer and recent widower, Augie. He has arrived with his three young daughters and teenage son Woodrow (Jake Ryan), a Junior Stargazer honouree for the weekend celebration for Asteroid Day, commemorating the moment a meteorite made impact with the earth in 3007 BC. Also visiting Asteroid City are movie star Midge Campbell (Johansson), and her Junior Stargazer daughter Dinah (Grace Edwards), ready to take part in the Junior Stargazers conference for bright young scientists. When the world-changing event of an alien encounter occurs, a strict lockdown is enforced, meaning nobody can leave the remote desert location.

Constructing a community

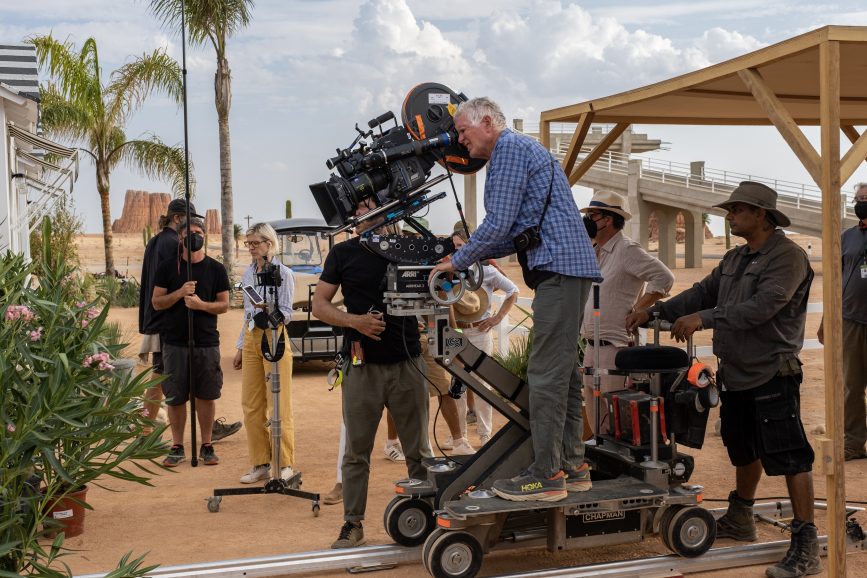

Anderson, one of his other frequent collaborators production designer Adam Stockhausen and the location scouting team found farmland on the outskirts of Chinchón, a small city in Spain, that perfectly suited the immersive Asteroid City world they set out to build, offering the ideal landscape, unobstructed views, hundreds of yards in all directions, and natural light required. The landowners agreed the farmers would not grow crops while the cinematic city was constructed, with the land becoming a blank canvas for Anderson and Stockhausen’s design.

“By the time I arrived, the bare bones were already there,” says Yeoman. “Everything was either captured at the town we built or locations in Chinchón we discovered that were modified in some way to help us create the world Wes envisaged.”

This method of creating a primary location where the production is based is Anderson’s preference. “I find that a more entertaining way to work,” he says. “We can focus on the characters and stay a unit.”

He has developed a unique way of working in prep and production that creates a family-like community of crew and cast. To ensure the desired style was realised in both worlds in Asteroid City he assembled a huge library of references such as films and books to offer inspiration to all, as he does on each project. “The actors and heads of departments all stay at the same hotel. This time production took place during the pandemic, and we all stayed in a hotel in Chinchón,” says Yeoman.

Two movies from the library that most influenced Yeoman in how to capture desert exteriors were Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984), shot by Robby Müller, and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), shot by William C. Mellor ASC. Bad Day at Black Rock was also a significant inspiration for Anderson and Stockhausen when crafting the look of the American southwest desert town. Shot on location around Death Valley and Mojave Desert, Bad Day at Black Rock provided real topography that Stockhausen duplicated with sculptors and painters. The black-and-white sections of the film taking place on the New York stage were set in theatre locations in Chinchón.

During prep, Anderson and Yeoman carried out a tremendous amount of testing before the actors arrived, exploring everything from colour to camera movement, saving time on set as precise plans were already in place.

“As the art department is building, we often shoot tests to determine what changes are needed. Repeat collaborators such as production designer Adam and costume designer Milena already know Wes’s vibe, but ultimately, he decides exactly what the colours will be as he has a clear idea how he wants everything to look which we then try to implement,” says Yeoman.

A hard lighting approach was adopted for the television studio set in line with how studios were lit in the ‘50s. In contrast, the colourful world of Asteroid City was lit naturally and relied on very few movie lights, particularly in the daytime, when almost none were used.

As Anderson was eager to shoot the colour segments naturally, Yeoman suggested incorporating skylights covered with full grid diffusion cloths into buildings such as the diner or gas station the team constructed where day interiors would be shot. “We’re not the first to do that – the early pioneers of filmmaking would put a large diffusion cloth on top of the set and let the sun light the actors,” says Yeoman.

The scenic and costume creations of Stockhausenand Canoneroalso integrated into the pastel-coloured look Anderson and Yeoman set out to capture on film. “Wes and colourist Gareth Spensley from Company 3, who we’ve also worked with previously, took it a little further in the DI to more of a low con saturated look than our more natural looking dailies,” adds Yeoman. “I immediately loved it as it gave the film a distinct look and took you back to the movies of the ‘50s.”

Capturing the energy on film

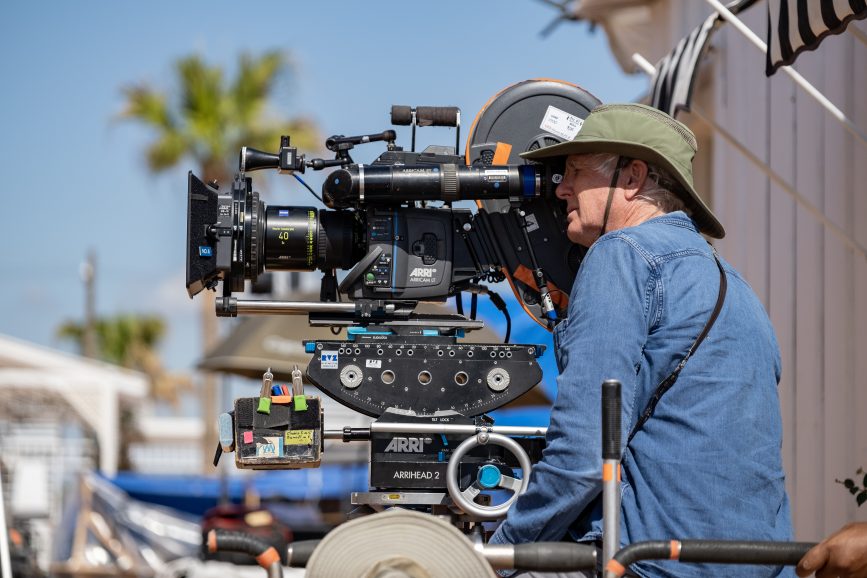

Anderson and Yeoman – who have always shot their collaborative productions on film – started working with the Arricam ST when capturing The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). “We were shooting in Germany and felt the German crew would be more familiar with ARRI gear,” says Yeoman. “The ST held up well in the winter when we were shooting and I just love their cameras, so we decided to work with the ST again for Asteroid City.”

They chose Cooke S4 lenses for the 1.37 black-and-white spherical sequences, having been impressed by how they rendered actors’ faces on previous productions. For the 2.40 colour sequences Yeoman worked with ARRI Anamorphic lenses which he and Anderson also used on past films.

“Even though people often associate Wes with centre framing, when shooting anamorphic we frequently have three or four people in a frame and sometimes the actors are more on the edge of the frame. I knew that the ARRI Anamorphics held focus beautifully all the way across the frame while some older vintage lenses are sharp in the middle and fall off towards the edges which would never work for Wes,” says Yeoman. “Like him, I’m a fan of everything being sharp, which we achieve shooting with pretty deep f-stops.”

With a passion for operating, Yeoman likes to be behind the camera on each production, believing that “while there’s no right or wrong way to operate” he and Anderson have “always shared a view on what the camera should do and how shots should be composed.”

“We’re blessed his movies always feature an incredible cast – just to watch them perform is a privilege,” he says. “I often think I’m the luckiest guy in the world as throughout my career, because I operate, I’m the first one to see the performance.”

Occasionally, in addition to the Arricam ST the Arricam LT was used with all kit supplied by RvZ Paris – a rental house in France which bought gear from ARRI Rental and also supplied equipment for The French Dispatch which was shot in France.

“There’s no handheld shots in Asteroid City, but occasionally we used the LT as Wes likes to leapfrog cameras, so while we shoot one sequence another camera has been prepared on a dolly so we could immediately move to the next shot.”

Although Yeoman also enjoys shooting digitally and it is great in low light, the highlights can start to burn in bright sunlight. Therefore, knowing Asteroid City would regularly see him shooting in the middle of the day in the desert and work with a great contrast range, he was confident film could hold the highlights, whereas digital capture might not have been as forgiving.

“Shooting on film also gives us great range and colour and has a special texture. The process is a little different on a digital shoot as the camera is often just left to roll,” he says. “When you’re rolling film, you have to be more careful. People’s attention is more focused on what they’re doing and somehow that energy magically ends up on the negative.”

On other productions Yeoman might shoot a fast stock inside and a slow stock outside, but as Anderson likes to work with one stock to achieve a coherent look, they selected Kodak Vision3 200T 5213 for the colour sequences, as they have for many years.

“Wes felt the faster stocks I’d tested in the past were too grainy. For the black-and-white sequences we used Eastman Double-X 5222 from Kodak which we started shooting with on The French Dispatch,” says Yeoman. “In prep on that movie, we’d shoot tests in colour and black-and-white, and often we preferred the black-and-white as its texture and grain would be difficult to recreate digitally. We fell in love with that stock on that movie and many things we originally were going to shoot in colour were shot using the black-and-white stock. Other than the anamorphic lenses being a new addition to our repertoire, it was the same cameras, kit, and stock we used on The French Dispatch.”

Artforms and animatics

Framing and composition – an artform perfected in Anderson productions – was precisely planned in animatics the director creates ahead of shooting. “These animated storyboards of the whole film are our guide and Wes voices all of the characters,” says Yeoman.

The whole town was built to accommodate the animatic which also outlined that in a shot featuring Schwartzman and Tom Hanks’ characters speaking to each other on the phone, they would appear side by side in split screen mode. So, on the matte box Yeoman used tape to indicate what part of each frame would be used.

“It allowed us to see exactly what we would catch on the left or right side of the frame,” he says. “Camera moves were challenging for these sequences. In the shot where Jason is in the phone booth, I had to do a 360 pan as police cars pass by chasing criminals. As I only had half the frame and it was a fast move, it was a more difficult shot than if you had the full frame. Timing was crucial as I had to move off Jason and come all the way around to find him again. So, compositionally it was important to have that line in the middle to see exactly where that actor would be and what the action was.”

Window frames and doorways are used as framing devices in Asteroid City, with the filmmakers always travelling with a viewfinder in prep to see exactly how things will appear in the frame. Occasionally Anderson might ask for a window to be moved or its size to be adjusted to align with the vision for the shot.

“Sometimes,if it’s an existing location, we would shoot tests on film without the actors, with production assistants stepping in as the cast, as we walk through the sequences and often set track before the actors get there,” says Yeoman. “When shooting outside we put marks on the ground, so we knew where the track would be on the day of the shoot.”

One of the opening shots which reveals the town as the camera looks one way and then the other, was precisely designed to accommodate Anderson’s love of symmetry and use of camera movement in the storytelling. “It’s not like we get there and say, ‘Why don’t we have a whip pan there?’ – it’s all already worked out,” says Yeoman. “Wes is very precise about what he wants, and it’s up to us to help figure out the best way to accomplish it.”

As the movement Anderson desires is so exact, it could not be accomplished using a Technocrane or Steadicam. Therefore, a tower cam on a track which can move straight up and down was used along with key grip Sanjay Sami’sinvention – a double track with one that allows the camera to move left to right and another enabling it to move in and out.

“Sanjay designs different varieties of track to suit the situation and mood which we also utilised when making The French Dispatch,” says Yeoman. “On the whole Wes is very low tech though and we don’t use Technocranes, but as usual we worked with dolly tracks that go on for forever.”

Capturing another extraordinary ensemble cast proved demanding at times as not all cast members were available at the same time. A long dolly shot at the beginning of the film introducing many of the main characters as they arrive into Asteroid City required the crew to shoot it in sections with whichever actors were on set at the time and then re-lay track sometimes several weeks later to pick up the other actors.

“This was made trickier as despite being in the desert, every few weeks, a massive rainstorm made the ground sink. When we put the track where it was previously, it wouldn’t match, so we needed to compensate for that,” says Yeoman.

Film-friendly theatrical lighting

When capturing the black-and-white sequences, the team worked with London-based theatrical lighting director, Matt Daw, who was brought on board to light a stage play in The French Dispatch which Anderson wanted to have a distinct theatrical look. “It added a whole new dimension to the look, so we brought him to Spain to help us create another world,” says Yeoman.

“My job was to try to blend and match how Matt was capturing the scene and make lighting ratios more film friendly to achieve enough exposure. In contrast to theatre lighting, our film is fairly slow at ASA 200, so I needed to boost the light levels. As Wes likes more depth of field, nothing is shot wide open, and I collaborated with Matt to combine our two ways of working.”

Daw worked with PAR cans, vintage 1KW fresnels, Martin Mac Aura XBs, Martin Mac Encores, and spotlights controlled through a dimmer board by lighting assistant Sarah Brown. “They were masters of the dimmer board because many times they needed to turn lights on and off as the actors moved around the set, something they often do in theatre, but we don’t do a lot in film,” adds Yeoman. “In the theatre world they accept having double shadows whereas in film making we try to avoid them, but it created a whole different feeling, more evocative of the television studio look of the 1950s. I think hard light often looks better in black-and-white shots – like you see in the movies of the ‘30s and ‘40s – it gives it a little more contrast.”

The journey of discovery Yeoman began on The French Dispatch continued with Asteroid City, demonstrating it is more difficult to separate elements when shooting with black-and-white film than colour, requiring more edge lighting, hard light and back light. Frequently when they were shooting in monochrome, they also turned their monitors to black-and-white. “It’s not exactly how it’s going to look, but it gives you a representation and showed me when we needed to add more edge lights. As a cinematographer, I enjoy trying to recreate the lighting of the ‘30s and ‘40s movies I love.”

French gaffer Gregory Fromentin who worked on The French Dispatch returned to collaborate with the team again, aware of Anderson’s preference to work with minimal crew on set. The stripped back approach was also adopted when lighting Asteroid City’s day exteriors. “We’d work with white cards and put silks on top of the building we were shooting,” says Yeoman. “Greg also worked closely with theatrical lighting designer Matt, rigging lights and ensuring they had the power required.

A life adventure

Alongside the stunning desert vistas, striking black-and-white world, and all-star cast, stop-motion elements were incorporated into the cinematic storytelling. Anderson once again teamed up with British stop-motion cinematographer Tristan Oliver BSC (Fantastic Mr. Fox, Isle of Dogs), who this time captured the alien (voiced by Jeff Goldblum) which unexpectedly visits Asteroid City.

“Wes is incredibly loyal to his key crew, I think because his vision and language are so particular and esoteric and he likes people around him who know his process,” says Oliver. “This is highly prescriptive, and the job is to get what he has in his head onto the screen and be willing to make many tiny adjustments and finesses to get to that place. Compromise isn’t an option and that’s what makes the collaboration so rewarding. You very rarely get that luxury of getting something absolutely right.”

The spaceship from which the alien descends, and the crater he steps into, were fabricated as miniatures, with no CGI used. Andy Gent and his team at Arch Model Studio (Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs), built a three-foot alien puppet – unusually large for stop motion work.

“Typically, animation puppets are between 25 and 35cm high,” says Oliver. “The alien was a metre tall and consequently the rigging for him was considerable – to stop him falling over – making it difficult to light around that structure. We even ended up building the crater on its side to get it into the stage as, scaled to the puppet, it was far too tall to fit upright.”

After being tested in London, Kim Keukelerie, a previous Anderson collaborator also renowned for her work with Tim Burton and Aardman Studios, picked up the work in France, animating the interstellar visitor.

Key crew working alongside Oliver were 1st AC Mark Swaffield and moco operator Stuart Galloway, with sets created by atelier Simon Weisse who has provided most of the miniatures for Anderson’s live action movies and specialist sets for Isle of Dogs.

Oliver shot the alien sequence on Canon EOS-1D X Mark III digital stills cameras, predominantly with Zeiss Contax lenses. “Recording everything in a variety of colours was challenging, so all our lighting had to be LED, predominantly Source 4 Lustre and ARRI SkyPanels. The spaceship was running over 1,000 channels of DMX’d miniature LEDs so we could flip from pure green to white and all combinations in between,” he explains. As ever, matching digital stills, shot spherically to anamorphic 35mm was interesting and I must thank my DIT, Ben Colson, for making sure we could achieve that match.”

The alien encounter sequence – a moment of wonder and confusion which sees a change in tempo and stylistic approach – was again storyboarded precisely before being shot in a warehouse against a giant rock wall which the team constructed. “We had two stages working at once as in another area of the warehouse, there was a green screen and second unit headed up by Roman Coppola capturing action elements of the story,” says Yeoman.

A roadrunner character – which scoots past as the freight train rolls along the tracks and a roadside sign reading “Asteroid City, Pop. 87” is revealed – was brought to life by London-based puppeteers Andy Gent and Olly Taylor. “Wearing green suits, one of them operated the legs and the other moved the head while music played which the roadrunner danced to,” elaborates Yeoman. “It was an intricate process which everyone loved watching as the puppeteers moved green sticks attached to different parts of the bird and which were later removed in post.”

Whether live action or stop-motion, clear communication with editor Barney Pillingis essential when shooting an Anderson production, a process that has evolved with each film the director crafts. “When I first started shooting years ago, everything was done in camera, but when Wes began making animated stop-motion films such as Fantastic Mr. Fox, it opened him up to different ways to combine things in post,” says Yeoman.

“Mostly everything is still in camera, but sometimes when we’re shooting, I have to be aware of how those elements will go together in the final frame in the edit. For example, occasionally we might not have an actor and need to put up a green screen up and comp that actor in later.”

Yeoman tells cinematography students he teaches that they should also take editing classes as it is an important stage in the filmmaking process they need to understand. “I’m not a great editor, but I feel like I understand editing to some degree, and when you’re shooting it helps to appreciate how everything will go together later,” he says.

“I always try to imagine it in my head, working with the animatics as a basis, as the final result is often very close. I’ve worked with directors where the end result is different to what I imagined, but with Wes it’s all pretty well mapped out.”

From animatic vision through to a family-like filming atmosphere, exploring the creative world of an Anderson set and the process of realising his vision is a unique experience Yeoman adores. “We all have dinner together whereas usually on other movies at the end of the day everyone goes their separate ways. Wes’s way of working is wonderful as not only are you making a movie, you’re also enjoying a life adventure together – one of the things I love the most about being part of his films.”

Yeoman seconds the statement made in an interview by Rupert Friend – who plays Montanain Asteroid City – in which he refers to Anderson as the conductor and the cast and crew as the instruments. “Wes knows what he wants. And it’s not like we don’t bring anything – we bring our own talents and unique perspectives – but you know what the parameters are which makes it easier to contribute,” says Yeoman. “The actors, for example, can bring something new that’s not on the page. Even back when we shot The Royal Tenenbaums, I read the script and thought, ‘Oh, I get this’, but then when I watched Gene Hackman perform, he brought a whole other element to it, and it was a pleasure to witness.”