IN THE MOMENT

Adopting a realistic approach based on newsreel footage and photographs of real combat, Rob Hardy ASC BSC helped realise Alex Garland’s dystopian story of a nation engulfed by the violent clashes of civil war.

Director Alex Garland and cinematographer Rob Hardy ASC BSC’s latest masterclass in cinematic world building sees them craft a dystopian and divided near-future in which a team of war photographers and journalists embark on a dangerous mission across America. Written and directed by Garland, Civil War imagines an armed alliance of states rebelling against the federal government and edging closer to pushing the capitol to a surrender.

While the reasons for the civil war are left for audience interpretation, the horror and violence in the fractured society are clear, as are the gruesome realities witnessed and documented by the war photographers and journalists at the story’s core. We see celebrated yet jaded combat photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst), her reporting partner Joel (Wagner Moura), young, aspiring photographer Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), and elder colleague Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) as they make their way to Washington D.C. with ambitions of securing a final interview with the president (Nick Offerman) before rebel factions descend upon the White House.

When telling such a poignant, powerful tale of conflict, especially during the current political unrest in some parts of the world, Garland acknowledged the importance of and difficulties in making a war movie that is anti-war and avoided sensationalising violence. “I took a particular approach to it, which was to do with naturalism,” says Garland. “For example, when people are shot, they don’t have squibs on them. You don’t see a huge fountain of blood. They just fall down. After they’ve fallen down, blood then leaks across the ground if they’ve been lying there for the right amount of time.”

Hardy agrees it is a vital and timely story to tell and that despite it being apolitical “due to the subject matter and in the current political climate, everybody has a version of what they think an American civil war might look like. We wanted to do something different to anything we’d made before and the film we created, from a visual sensibility, is abrasive which I think suits the topic.”

Adopting a documentary approach based on imagery audiences would have seen in newsreel footage allowed the filmmakers to capture violence in an authentic way that is true to real combat rather than glamourising it. “Very few shots in this film use tracks and dollies and the normal architecture of shooting a film,” adds Garland, who whenever possible used full flash blanks, with safety always a priority. “People around them react differently. The noise those things make is loud, and some of them, like 50 calibre guns, create almost like a vacuum in the air that is almost like someone tapping your chest.”

Hardy first read the script when he was in Atlanta prepping a film that did not materialise due to the pandemic. “It was born out of another idea of Alex’s about the start of a revolution, set within a square mile in New York,” he says. “He has fast and slow scripts, and this was one of those fast scripts that just poured out.”

Like Hardy, A24 was immediately on board but as logistically it felt difficult to shoot on the back end of the pandemic, Garland wrote and then shot the “more contained” story of MEN with Hardy before going into battle on Civil War. The action-packed war movie not only marked a departure from Garland and Hardy’s previous four collaborations, it was A24’s biggest budget production to date.

Amidst the chaos

The filmmakers were not aiming for “the same kind of elegance” as their productions Ex Machina or Annihilation, but Hardy admits they “always like to drop in a bit of surrealism. We work our way through genres, we hit drama-related sci-fi quite a lot, MEN could be considered a horror, and our latest film is part war film, part road movie.”

Breaking the story down into a “more traditional way” of shooting, the filmmakers also considered the military action aspects, aiming to achieve an immersive cinematic experience in which the audience felt they were amidst the action with the photographers. Rather than capturing it from an outsider’s perspective, Hardy wanted the audience to “feel the chaos in which those photographers and journalists work”.

As he had enjoyed working with the Sony Venice and Panavision H Series glass on films such as MEN, this formed a starting point for Civil War’s camera package, upgrading to the Venice 2. “The beautiful 55mm H Series is my favourite Panavision lens and we also used a 75mm and 100mm from that set as they all do something special to the image,” says Hardy.

The filmmakers – who had often used Steadicam and Stabileye on their previous films – reverse engineered sequences to find solutions that were adaptable to shoot military operations. This time they sought a different technology to fulfil their visual ambitions, offering handheld opportunities as well as elegance.

They wanted to plan the choreography, design and light the environments and then “just go in with the journalists as if we were filming it live” and needed a device to make this possible and “feel like it was happening in the moment”.

The DJI Ronin 4D – a new camera they had heard about while grading MEN – fit the bill. Hardy calls it “the chicken because it’s about the same size and works on a Z axis so when you hold its body and move, the body can go up and down but the neck and head stay still. At any moment you could go into handheld mode or it could feel like Steadicam. It was also relayed back remotely, so I could be on the wheels and talking to an operator in the action over comms.”

Like previous productions, Garland wanted Hardy to be in control of the frame. “As Alex and I practically see the same thing the whole time, using the Ronin 4D felt like a great way to operate with me controlling the framing precision,” says Hardy. “I could then sort of let go and we could enter the chaos, go into handheld mode, and then do the handoff again and I’d instantly be back controlling the frame.”

In addition to two Venice 2s, the production relied on six Ronin 4D cameras which Hardy compares to “an armoury”, each camera paired with a different lens to save time. Panavision created rigs for the Ronin 4Ds to adapt them to the production’s needs, attaching cages to parts of the camera and making it possible for them to work with remote focuses.

Mounts were machined so Leica M 0.8 still photography lenses could fit onto the 4D cameras and Panavision’s Dan Sasaki detuned a set of the lenses to match the flavour of the H Series paired with the Venice. Nikon Nikkor lenses were also used for some car work, adding to the photojournalistic feel.

“The edging dropped out to a certain degree when working with the detuned Leicas, so we could sometimes force a more surreal look,” says Hardy. “For Lee’s flashback sequences to past war photography experiences, Alex was keen to press in a harder look, whereas I believed everything should feel the same. In the end, I think riffing off the Leica’s detuned nature works really well, with some additional work done in post.”

Finding moments where a surreal approach might add to the visual storytelling is a technique the filmmakers have perfected since their first collaboration, Ex Machina. It was deployed for a distressing scene in Civil War when Jessie falls into a pit of bodies. “I was in there with her, shooting on a Ronin 4D and super close focus macro Leica lens with a dioptre,” says Hardy. “That experience was harrowing for us both. Once we were in that pit, we both wanted out.”

Although the decision for the film to be shown in IMAX was made once A24 had seen an early cut, Hardy believes it is “IMAX in its truest form and a real cinematic experience” as the filmmakers approached it “in such an immersive way, it begs to be seen on the big screen”.

A snapshot of combat

While Garland and Hardy avoid being influenced by other movies, due to Civil War’s subject matter the visual approach was born out of newsreel and stills from war zones by photographers such as Lee Miller. Central to their approach, says Hardy, is “creating the world, and then entering it” and on this occasion “creating our own version of war photography. If you imagine a still from a war zone, you consider how it was captured, what got them to that moment, what happened after, and everything outside that frame,” he says. “You’re bringing this frozen moment in a world of chaos back to life.”

One of the first aspects discussed was how to capture and incorporate stills taken by the photographers to intersperse throughout the film. “Lee is war torn but she’s a legend, like Lee Miller. So, whenever her images appeared through her Leica digital camera, they needed to be mind-blowingly brilliant,” says Hardy.

A high-speed camera captured snapshots in scenes such as one that played out in a set designed to feel like East Africa where a war was taking place. In the distressing sequence a tyre is dropped over a person, before they are set on fire. “We designed the scene around that moment Lee captures the image and set up a RED Raptor camera to shoot at high speed so we could select the exact moment we wanted in the film,” says Hardy.

“Cailee (Jessie) – who shoots on film with a Nikon camera – and Kirsten (Lee) would produce images throughout the shoot which we’d sometimes use and lean into, take our own stills or lift images from the Venice or Ronin 4D footage to place in the movie.”

Presenting events in an observational way that did not glorify war remained at the forefront. In line with Garland’s aims, Hardy “wanted to show the experience as it really is. Where you are in the world, who’s fighting who, and their political allegiance becomes irrelevant when it’s simply people shooting at other people. That was our baseline and the part of the world we inhabited.”

Working closely with military advisor and ex-Navy Seal, Ray Mendoza, much of the action was designed to be authentic and based on real combat. “That more handheld look when it comes to combat, is the way I view things,” says Mendoza. “Watching these handhelds – it’s more visceral. That’s how you view your life, when things are fast.”

Giving the cast and crew space was also crucial, so Garland and Hardy looked at the action and then shot listed on the day to allow that freedom. If a moment was missed, the filmmakers reshot it until it was captured how they wished. “Sometimes long takes became shorter if we still felt we weren’t drilling into a specific aspect, glance or way somebody moves – those things are very important to the cut,” says Hardy.

When shooting such sequences, Hardy feels fortunate to have formed a collaboration with a director who “is a proper filmmaker”. While each of their films is different, their approach and partnership remains the same. “When Alex is choreographing a specific scene, and I’m lining up with a lens, he knows what I’m looking for, and if I’ve found something. It’s a free flowing process that feels very comfortable.”

Along for the ride

Although rarely storyboarding sequences unless they are visual effects heavy, for logistics purposes, Garland and Hardy determine which scenes will need to be surreal or precise. “We wanted the film to feel surprising and unpredictable, because it was structured like a road trip, a simple journey from A to B, and we wanted the audience to come along for the ride,” says Hardy. “We’re all on that journey together, we don’t know what’s going to happen or what the next stop will be.”

Civil War was shot in and around Atlanta, with some sequences captured in New York and a small amount of B roll in Washington. Hardy and Garland scouted Washington early on, not to shoot, but to view the approach to, streets either side of, and barriers protecting the White House, in preparation for filming the climactic sequence.

As the sequences got bigger – especially those around the barrier at the White House – they were broken down into sections, allowing multiple beats to be hit amongst the bedlam. Hardy and Garland sat around a table in what they referred to as their “war room” to choreograph the combat scenes, using models to plan where people, tanks and cars would move. They looked at what was inside the real White House and sequences that needed to unfold there. One significant event during the siege scene was a point of reference, “and the whole military operation was reverse engineered around that moment”.

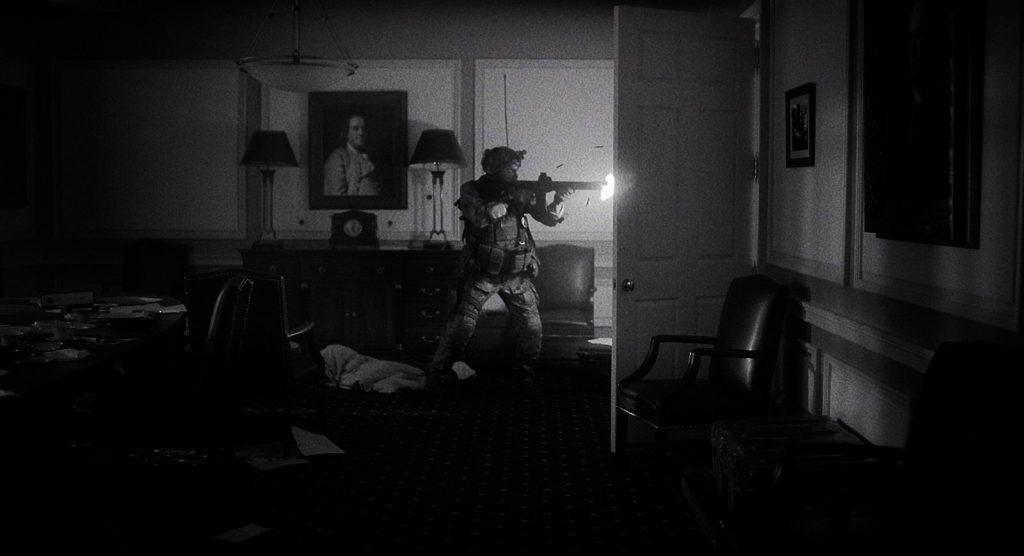

“Sightlines were a constant consideration as people were crossing and passing through doorways so it became chaotic,” says Hardy. “So we built two rooms either side of a corridor, and did what we always do – move our way through the sequence incrementally. Step by step. It was very full on and loud as my operators moved into the area while I controlled on the wheels.”

The closer the war photographers get to Washington, the more disturbing their surroundings become. To achieve this production designer Caty Maxey reappropriated places such as a car wash behind a gas station where horrific scenes unfold and an old college football stadium which was transformed into a refugee camp.

Originally, the White House sequences were to be shot at Tyler Perry Studios in Atlanta at a set built for a comedy about a family living in the White House. Although used for some sequences of the entrance, it could not be used for combat scenes due to the damage that would be caused. Other locations in Atlanta were also scouted and a plan was in place to fly helicopters between buildings but it was deemed logistically problematic as it would need to be shot over five nights.

Due to the noise and disruption from tanks, gunfire, and explosions as the Washington Monument was blown up in the final pulsating sequence and siege of the capitol, part of the set was constructed from the ground-up and filmed in a coach parking lot on the outskirts of Atlanta. “It was decided for all the right reasons, safety among them, we would build that block,” says Maxey. “We built 400 foot long buildings [and] two sides of the street in three and a half weeks.”

Hardy was wowed by Maxey’s creations and praises the “amazing job she did designing everything including the barrier and two streets approaching it, building the Oval Office and the corridors leading to it”.

The road trip portion of the film needed locations that felt “recognisably everyday American” – malls, chain food stores, multiplexes. “The challenge was taking those places and transforming them, so we looked at derelict locations and some that were still functioning,” says Hardy. “We did some roadblocks to stop traffic and shut down highways so we could fill them with burning cars.”

Hardy and Garland made a surprise discovery at a farm they were scoping out. “There were a few farmhouses and one big house which looked like the Overlook Hotel from The Shining. In front of it was a discarded Winter Wonderland with fake snow, Santa Clauses, and dioramas,” says Hardy. “The land owners were in the process of tidying up, but Alex and I asked them not to move anything as it was amazing. We knew, in that moment, it had to be the location of the sniper scene. It was a gift.”

Driving sequences – many of which took place in and around the Winter Wonderland location – were carried out using three types of vehicle: a pod car with a stunt driver on top controlling the vehicle for the actors inside the car; a free drive car which the camera crew would jump in with the Ronin 4Ds to cover specific moments outside of the basic coverage and many exterior sequences; and a coverage car.

“The coverage car allowed us to hit all the beats and achieve basic coverage of the four characters in the car before elaborating on specific moments,” says Hardy. “The actors could just jump in and drive and we’d have in some cases 20 cameras in and around the car – two Venice 2s on the front and the rest were Sony Alpha A7S III with the H Series lens. They would be on the outside looking in to capture glances out the window, and some were inside cross shooting.

“We didn’t need to think about the cameras because we could shoot from anywhere at any moment, giving us freedom in the choreography. The actors could play out the scene in full and in real time while we travelled in a follow vehicle with many monitors so I could constantly tweak and make adjustments to filtration, NDs, lens size.”

Despite expecting the cameras would need to be painted out in post, only a few reflections were cleaned up as the cameras’ small footprint and positioning meant they were not in shot.

Controlling the frame

Needing a member of the camera crew and technician who understood the DJI Ronin 4D technology – which was new at the time – Hardy turned to camera operator and Ronin 4D technician at Panavision, Chris DuMont. While 1st AC Ryan King, who has collaborated with Hardy on productions such as MEN, was not able to be part of the Civil War crew due to restrictions on UK crew working in the US, he helped with much of the Ronin 4D prep work, teaming up with DuMont to create a slick way for the US crew to handle the technology.

“At this point, the 4D was brand-new technology, so we brought Chris to Atlanta to train the operators and focus pullers how best to utilise them,” says Hardy. “He was integral to the process in that respect and later, as the production expanded, became one of the many operators on the film.”

As DuMont highlights, the Ronin 4D is unique as it stabilises three axes as well as the fourth Z axis, allowing it to move up and down. “It’s similar to what a conventional Steadicam does for the Z axis. The 4D’s compact size enables you to achieve shots you could do before, but in a different way,” he says. “When the war photographers are in those combat zones, surrounded by the energy of the scene and they bring the camera up to get a shot, we needed to find a stillness in that moment which these camera systems enabled us to do.”

Capturing a sequence of soldiers entering a commercial district and climbing a staircase into a building on Steadicam would require working in sections, shooting each set of steps at a time. But the Ronin 4D allowed them to shoot the entire stairwell – an operator walking forwards with the camera in the other direction while Hardy was on the wheels at the bottom of the steps controlling the frame.

“To move the camera through that small space would be difficult with traditional tools, but the Ronin 4D allows us to move through that space, and you can’t feel any footsteps of the operator in the shot, which would make you suddenly aware there’s a person there filming,” says DuMont. “Alex and Rob wanted to create a space the actors and operators could move freely within. With the Ronin 4D we could be in the middle of the action. With Rob on the comms, we worked together to find the shots and it was a very fluid process.”

The film in some places lent itself to being fluid and handheld and in others suited a dolly movement which was possible with the Ronin 4D as the operators could switch between different ways of shooting and also be close to and move quickly with the actors.

“If you’ve got four of the systems running, it’s almost like having four Steadicam operators running at the same time. But as we were working with a small handheld package it gave us the freedom to capture footage without getting in the way of other operators.”

Civil War being largely shot chronologically aided the operators and more importantly the cast by giving them the rare opportunity of experiencing the story in real time. Hardy and Garland would set the initial framing for each camera and once the action played out the operators responded to the moves.

Hardy’s visual approach remained very photographic. When taking a picture of someone on a 50mm lens on a still camera, his natural instinct is to centre them, give them a little headroom and make it a sort of mid shot, so you feel the environment and the image says something about that person. “I wanted to translate that into the moving image, based on how I’d take a photograph and instil that idea of framing with the operators,” says Hardy.

Due to the energy surrounding what was playing out in each scene, it “felt very real in the moment” for cast and crew, and DuMont admits that sometimes as an operator it is difficult to avoid being pulled in. “You don’t want to start suddenly being shaky or jump if a gun or explosion goes off near you, so it’s about trying to calm yourself in that moment whilst still being connected to the action,” he says. “You have to take that time to slow down your breathing and separate yourself from the energy around you so you can feel and focus in on that moment. It has been one of the best and most important experiences of my life as you often learn the most from the challenges you face.”

As well as knowing he was working on something special, DuMont was struck by the pertinent political timing of the production. “I doubt I could work on a film that has so much political significance in the current climate we’re in,” he says. “It was an incredible experience working with Rob and one I will always be grateful for.”

Sequences of a military style camp staged on a ranch in rural Georgia required aerial cinematographer Dylan Goss and his team to work with the main unit. The shots established the scene, introducing the camp by way of following a military helicopter, with pilots Fred North and Ben Skorstad flying. “We brought a camera ship (helicopter) and a picture ship with dummy missiles and machine guns mounted to it, props that Fred provided with the aircraft,” says Goss, who worked with Garland and Hardy on series DEVS (2020), shooting on a splinter aerial unit.

Knowing he would be filming the second aircraft “and with so much production value on the ground”, Goss wanted a flexible solution that avoided unnecessary lens changes, opting for a large Shotover K1 gimbal from Team5 in Los Angeles to house an equally large Angénieux Optimo Ultra 12-1 hero lens, setup in Full-Frame at 36-435mm (12.75kg).

“I love that Rob looks at what we do very non-traditionally,” says Goss. “He was more interested in the shot and where movement worked best (or didn’t) than obsessing on staying front-lit for each frame. He wasn’t afraid to consciously break some rules, which gave me confidence in following his lead.”

Embracing the rawness

Gaffer Todd Heater first met Hardy on a 2016 commercial shoot before collaborating again on DEVS. “I jumped at the chance to then work on Civil War as collaborating with Rob and Alex is an honour – it’s one of the best experiences in my 33 years of doing this,” he says. “They are visionary and dedicated to the script, visuals, craft, and people around them.”

As well as helping achieve the non-artificial look required, Heater offered the ability to shoot in any direction. “Alex is a visual director and sometimes sees something he likes which is not exactly part of the set. For a rooftop scene, we shot in a room on top of a building at short notice and had to adapt using what small incandescent units were available,” adds Heater. “Just about every exterior set we could shoot in all directions as I staged lighting in places we’d not normally look, to be ready on the fly.”

Hardy’s propensity is to work in a 360 degree environment and use tungsten and large units like Wendys or Dinos. “I love polluting tungsten with existing daylight which Todd really understood and enabled, helping me navigate the textures of light,” says Hardy. Production designer Maxey worked with Heater and Hardy to retrofit fixtures into sets such as fixing bare 2K incandescent bulbs to the wall of the barrier at the White House so they photographed like a real light.

Heater agrees incandescent lighting – with which Hardy mostly likes to work – creates the most natural look on skin tones. “Many gaffers and cinematographers of the past would use large banks of Wendys or Dinos blended with ambient daylight to create a beautiful, natural looking source. HMIs always look very artificial to me and we didn’t use any on this film.”

As controllable lights that could mimic stadium-style lighting were needed outside the White House, LED fixtures featured in the night scenes. “They had to be flicker-free, full colour and IP rated and look like they belonged to the set we used 24 Fiilex Quad Color lamps fixed to light tower poles that could be moved on Manitous,” says Heater, who also used ARRI SkyPanel S360s for large moon boxes and a few S60-Cs rigged into soft boxes in the White House set ceiling.

While avoiding seeking visual motivation from films, Hardy highlights Amadeus as his sole movie inspiration for one location. “I wanted chandeliers similar to those in Amadeus to create a glowing beautiful effect inside the White House – juxtaposing with the horror and harshness the audience goes through during the rest of the film.”

Almost all day work was shot using natural light because, as Heater highlights, “a war film is not supposed to look nice, meaning we let almost everything go we’d normally take control of”. It was sometimes difficult for him “as it’s natural instinct to make things look more beautiful but we had to embrace the rawness”.

As most of the film is shot outside on location in Atlanta, changeable weather disrupted plans. When shooting the military raid on an abandoned building, lightning struck within a 10-mile radius of the location, and the generators were shut off for 45 minutes to abide by regulations. “Alex was frustrated, as was everyone, that we couldn’t complete the day and asked if there was anything we could do inside without power,” says Heater. “So we shot that scene with a mixture of ambient daylight, flashlights on the weapons, Astera Titan tubes, Digital Sputniks, all battery-powered fixtures.”

Heater highlights a stunning and surreal scene when the photographers and journalists drive through a forest fire as one of the most unusual: “It was not so much the technology but that we used a combination of real fire and Dinos to create the fire which even while filming it looked very real and frightening.”

It’s also a sequence Hardy believes stands out visually amidst a filmmaking experience which whilst rewarding was also one of the most intense he has experienced. This was in part due to the way he and Garland set the shoot up to achieve authenticity, with a small footprint while filming that meant the crew felt like journalists within the action.

“The actors also felt the impact because there was no facade of cameras or lights on set. It felt real and I think it would have been tough for the actors,” he says. “But as challenging as Civil War was from a subject matter perspective, we all felt we were going on this journey together and there was a sense of camaraderie. Thanks to the way Alex’s scripts are written, you’re never in the same place for long. It’s always a new experience and we had this amazing sense we were part of the same adventure which made the shoot easier.”