LOCKED IN REALITY

A couple in the process of separating who are forced to continue cohabitating due to lockdown restrictions are presented with obstacles and opportunities in director Doug Liman’s poignant yet often amusing portrayal of a pandemic era relationship that builds to a heist crescendo.

With the narrative of Locked Down centring around a situation the whole of society has been confronted with – the strains and uncertainty caused by the pandemic – the primary ambition was ensuring the film captured this unusual period in a truthful and believable way.

Like Doug Liman’s Swingers (1996) and The Bourne Identity (2002), the director wanted much of his most recent film to be shot handheld to ensure it felt real and immersive.

Initially, Liman planned to shoot and direct, having taken on both roles for his first feature Swingers, but due to Locked Down’s short shooting schedule of 18 days and Liman’s desire to collaborate as closely as possible with the actors, he opted to focus purely on directing. Producer Richard Weyland suggested Liman look at the work of British cinematographer Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC – with whom Weyland had previously collaborated on Band of Brothers (2001) – when selecting who would capture the world portrayed in the multi-faceted script penned by Stephen Knight (Dirty Pretty Things, Locke).

“I love Stephen’s writing and the concept explored in Locked Down,” says Adefarasin. “His scripts are so diverse but they’re all about humanity and the way people react to situations. This story really appealed because it was about a situation we all continue to suffer. Stephen, Doug and I also share a love of working on a variety of genres, so it was a no-brainer for us to team up.”

When Liman rehearsed scenes with the actors, Adefarasin used Artemis, a trusty app that has proven invaluable for many films he has lensed. He took stills with it to later discuss with the director when exploring how best to structure each scene. “The app also includes a movie mode, so you can record a tracking shot or suggest the camera move inwards at a certain point, for instance. Doug also had the app on his phone, so we both took shots and then could easily examine the best way to shoot each sequence, saving an enormous amount of time.”

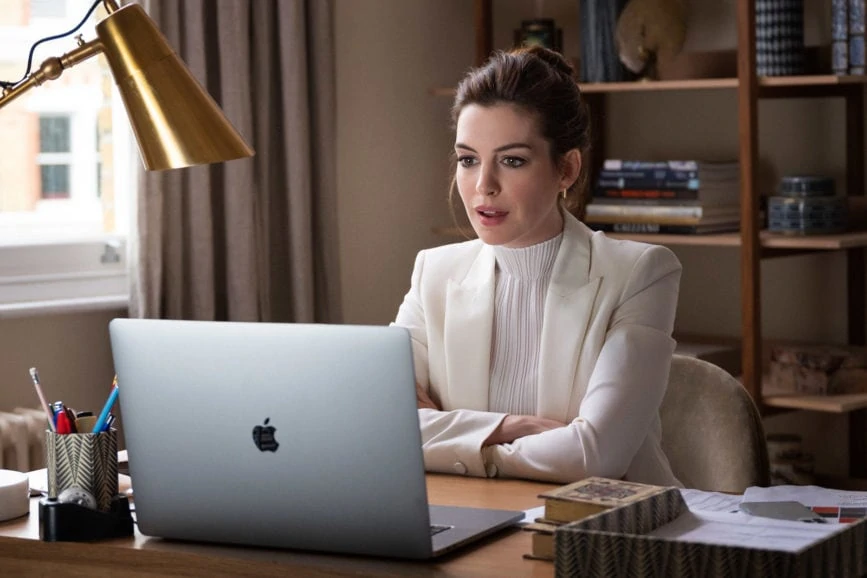

As most of the narrative unfolds inside the house in which the couple are trapped while their relationship deteriorates, it was important to clearly establish its layout through the film’s visual storytelling. “Linda (Anne Hathaway) lived downstairs, and her partner Paxton (Chiwetel Ejiofor) lived upstairs in the attic, so we tried to convey that through shots of him going up and down the stairs and passing or knocking on her door.”

The house location, based in Clapham, London, required some minor redecoration before shooting. As glass protecting precious paintings could not be removed from the walls, the crew had to be mindful of reflections when shooting. Much of the short pre-production period was spent scoping out Harrods, the other prime location where the later heist action plays out. “We visited the vast store three times and I walked about six miles to select the best areas to shoot,” says Adefarasin. “We needed to film some scenes in a safe, so we visited other buildings to see if they offered more cinematic options but eventually decided to film in Harrods’ own safe.”

Videocalls, a staple of lockdown life, were also incorporated into the narrative and needed to be meticulously planned when working with cast members in different time zones. The budget would not allow for camera crews to visit each distant location in which the actors were based, so footage was recorded from their computers or phones and sound recordists were sent to each location to capture clean audio. Budget was allocated to aspects of the shoot such as filming sequences of lead characters Hathaway and Ejiofor on a motorbike or in a van traveling around London which required a second unit, crane and remote head.

The whole team did an incredible job in the challenging circumstances resulting from the COVID restrictions and confined spaces. For example, filming in real locations meant we were limited by the height of the rooms in the house.

Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC

Adefarasin, who operated on the production, was joined by a tight-knit crew including 1st AC Julian Bucknall, 2nd AC Alex Collings, central loader Dan Glazebrook, key grip Jack Flemming, boom operator Orin Beaton, gaffer Pat Sweeney, and best boy Martin Conway. Aligning with the film’s core theme, pandemic protocols were adhered to throughout, with all crew wearing masks and having three COVID tests a week.

“The whole team did an incredible job in the challenging circumstances resulting from the COVID restrictions and confined spaces. For example, filming in real locations meant we were limited by the height of the rooms in the house. There were challenges for Orin not only when boom operating but fitting the radio mics. I have an upmost respect for the actors too who were phenomenal working with demanding COVID conditions, a tight schedule, and a complex script.”

With many years of experience of shooting documentaries, Adefarasin is familiar with the multitude of techniques adopted to light a range of environments which can be applied to shooting other types of productions. “Sometimes when you need to take risks and experiment you can find that shooting with little or no light looks better than an overly lit shot. You learn a lot about lighting just from the necessity of having to do it with limited resources,” he says.

“On this occasion, gaffer Pat Sweeney made some amazing small battery-powered LED lamps with magnetic backings that could be fixed to beams. Elsewhere, we didn’t have cherry pickers, big towers or cranes for the shots filmed in or around the house – we lit mostly using ARRI M8 and M18 HMIs and tiny Aladdin A-Lite LED lights.”

As Adefarasin knew there would be an element of handheld, he opted for the ARRI Alexa Mini LF due to the quality it offers in such a lightweight body, paired with ARRI Signature Primes, from 18mm up to 150mm, because they are also “light and incredibly beautiful lenses.” “I like to get the look of the film as close to how we want it in camera, so we had a calibrated monitor on set. This meant Doug knew the direction it was going in and we later worked with Goldcrest colourist Adam Glasman to refine the look,” he says.

Adefarasin initially underestimated quite how much of Locked Down would be shot handheld. At the end of filming, 1st AC Bucknall added up the footage on the data cards and worked out the cinematographer had held the camera for more than 50 hours during the 18-day shoot. “This film reinforced how fantastic shooting handheld can be. On the production I shot after Locked Down and have just completed (Shekhar Kapur’s What’s Love Got to Do with It?) I suggested shooting some scenes handheld which I normally might not have done. It’s really opened up my awareness of the beauty of handheld.”

“This film is bittersweet in a way because the situation is still ongoing, but when COVID fades away I believe people will see Locked Down as an important record of the state of England during this unprecedented time.”