From stadium to screen

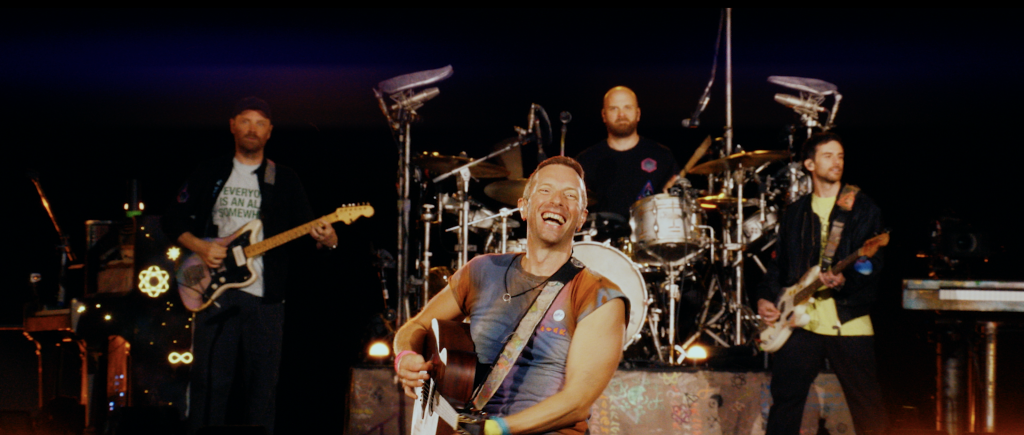

Adopting a cinematic approach when lensing Coldplay’s concert film, director Paul Dugdale and cinematographer Brett Turnbull captured the band’s vibrant performance and production, alongside the atmosphere in the stadium and connection between artists and audience.

One of the first concert films cinematographer Brett Turnbull and director Paul Dugdale collaborated on was Coldplay’s 2012 wild and wonderful production at Stade de France in Paris. A decade later – and having captured more of the band’s shows along with the live performances of some of the world’s biggest artists – the filmmakers joined forces to shoot Coldplay’s vibrant show at River Plate stadium in Buenos Aires.

The shorthand Dugdale and Turnbull have developed is built on shared references and aesthetics and an openness to trying new techniques and creatively and technically pushing the limits of the genre. On this occasion they were capturing a live broadcast and a post produced version of the production to be screened in cinemas.

“We only ever have one chance at a global live broadcast,” says Dugdale, “the stakes are incredibly high so selecting a team who are experienced and creative, but also aren’t in danger of choking under pressure is vital for a high-level live capture.”

The themes and conceptual ideas that flow through the band’s music and live shows is key for the director. “To a certain extent we are there to work as documentarians, faithfully capturing a performance, but in addition to that, we want to try to complement the tour’s overarching themes and use those as a guide to inform the style in which we shoot,” says Dugdale. “In this instance the interplanetary, deep space imagery that features through the show really informs its identity so using cameras which gave a sense of extreme movement through space felt like a perfect match to try to complement that creative narrative and translate it into images.”

As CinemaScope fans, the filmmakers shoot many of their shows in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio to convey a sense of epic scale and show relationships between the band in deep two- and three-shots. “This takes pressure off having to cut constantly between them, like most live TV presentations,” says Turnbull. “Knowing our primary audience would watch on a big screen at cinemas also meant we could often play things wider.”

Planning makes perfect

Dugdale either contacts Turnbull at the development stage to explore new or unfamiliar techniques or brings him in once the project is greenlit to work alongside him on camera plots. When translating the director’s ambitions for filming the show into accurate and detailed floor plans and kit lists, Turnbull must first understand the creative intent behind each camera placement, from shot size through to the role camera angles will need to play in the edit.

Understanding Dugdale’s vision informs lensing and grip equipment choice, but unlike conventional film production, they are unable to place cameras where they wish or dictate set and lighting design. “But taking a passive documentary approach would yield disappointing results, so a complex process of negotiation follows,” highlights Turnbull, who requests scale drawings of the stage set and rigging, or ideally a 3D model, placed accurately within the arena or stadium.

Fortunately, most big tours can provide CAD plans as the technical complexity and scale of their productions demands it. The cinematographer adds layers to these technical drawings to accurately plot camera positions, and the space needed, enabling him to measure distances and calculate lensing and shot sizes from each angle. Using 3D stage and venue models, he can insert virtual cameras to previsualise the shots. Reviewing this previz material with Dugdale then solves problems at the design stage.

As bargaining for effective camera positions in prime locations can make or break a concert film, plotting accurately helps get proposals over the line. “Showing up at a stadium with a truck of gear like a bunch of Hollywood big shots, throwing it down and then asking to move it ten times, is not going to win hearts and minds,” adds Turnbull.

Scouting the show, which on this occasion Turnbull carried out at Wembley Stadium, also allows him to experience the production from an audience perspective and “get a sense of the atmosphere and emotions of the crowd as ultimately a successful concert film needs to convey this, and the connection between the artist and fans.” The cinematographer was also fortunate to co-ordinate his visit with meeting Coldplay’s lighting designer, Sooner Routhier, and set designer, Misty Buckley, to learn more about the design concept, and creative evolution of the show.

Turnbull walks the stage, pit, and other technical areas and documents all hardware that does not appear on drawings and might obstruct where the team hopes to place cameras. By meticulously photographing all kit, he can later reference the images when fitting the camera and grip gear around the show’s essential hardware.

Having seen a creative brief for the show’s production, Dugdale could also appreciate its relevance to the overarching album and story. “The camera plan is the blueprint for everything,” he says. “Particularly with a live show like this – where principal photography was over two nights and we shot a couple more nights with additional cameras – securing effective positions is immensely important.”

Based on watching the show and research, Dugdale and Turnbull’s document includes camera roles and scripted shots for all cameras for every song. “The whole stadium becomes the performance space, so our camera plan must be agile and guarantee we have good coverage,” says the director. “I direct live, but because we had around 26 cameras per night for that show, you just can’t communicate that quickly, so it’s useful to have a cheat sheet meaning everyone knows where they should be, and where the band will move.”

Realising the designer’s intention

After watching the show with Routhier, Turnbull visited Wembley once again to shoot test footage with a Sony Venice 2 to enable him to accurately evaluate the show lighting and identify any issues with video screens and lasers. He puts his test footage onto a timeline in Resolve or Premiere, and adds notes about T-stop, and ISO as captions, so when he later adjusts and balances these aspects of the show prior to filming, he has a quick and easy “before and after” visual reference.

Getting time for a pre light session with the show’s LD is always a challenge, as touring schedules can be brutal, and at outdoor venues lighting work can only take place after sunset. Turnbull was able to join Coldplay’s lighting director Shaheem Litchmore and his crew at River Plate stadium for their load-in, to ensure all follow spots and LED video screens were set up sympathetically for the cameras. Although colour meters are now very sophisticated, he also made sure to have a Venice camera and a good reference monitor at the lighting desk.

“Most theatrical lights used on big shows nowadays are LED fixtures with low CRI ratings, and the meter can be misleading in some cases. On shoots like this you generally get one chance to fix things, and need to work fast,” he says. “Seeing exactly what you’re going to get, on camera, is helpful. After setting spots and key lights, we also ran through all the show’s colour palettes for each lamp type, making any adjustments necessary to ensure that a cinema audience would be seeing colours as true as possible to the designer’s intention.”

Lighting programmer Joe Lott, who originally worked on the show during rehearsals, joined Routhier and Litchmore in Buenos Aires and ran an extra lighting console dedicated to the crew’s filming needs. “Together we could embellish the existing audience lighting, and override the main show desk to adjust intensity of the automated follow spots, key lights and other selected lamp groups during the show,” says Turnbull, who prefers to be at the FOH lighting position when shooting live, with an array of matching reference monitors spread between the different control desks, so the tour lighting and video operators can also see how the show looks on camera. Fine tuning lighting and video screen levels is then possible on the fly.

As filming from cameras 360 degrees around the stage in changing atmospheric conditions, with haze and pyrotechnic effects, is challenging, being able to react instinctively to how the cameras are seeing the band, from all angles is vital, “especially as you don’t get to see most of those shots, until you’re already live on cinema screens around the world.”

A prominent element of the lighting design was strobe/flood battens facing outwards, in saturated colours. Routhier agreed to have their intensity physically reduced by taping ND gel over the front of the lamps. “Otherwise, they would just bleach out,” says Turnbull. “Lamps designed for rock ‘n’ roll are getting brighter every year, and don’t behave well if you’re trying to run them way down at the bottom end of their dimmer curve, so there comes a point where you simply have to resort to old school methods to cut their output.”

Camera flicker is problematic when working with LED lights, especially when dimmed. Luckily many lamps can now run at higher refresh rates, so all types were thoroughly checked on camera and adjusted where necessary. “Lasers also flicker horribly on-camera, and there’s no magic one-button fix for that, as every laser effect tends to run at a totally different frequency,” adds Turnbull. “Coldplay’s laser tech kindly tuned every one of their cues on camera during our overnight session, to “freeze” the laser beams on screen.”

Explosion of colour and light

Turnbull created pre vis documents so he and Dugdale could review lensing several weeks ahead of shipping the gear from Europe. They used a large variety of lenses for a multitude of camera positions and cameras with different roles. The majority were full frame zoom lenses, with focal length range based on camera positions and included Angénieux Optimo Ultra 12x 36-435mm and lightweight EZ series 22-60mm and 45-135mm; Fujinon Premista series 28-100mm and 19-45mm; ARRI Signature Zoom 16-32mm and 65-300mm with 1.7x extender; a basic selection of wide-angle Zeiss Supreme primes; and Entaniya fisheye HAL220.

Multiple companies supplied the kit, each delivering specific aspects in line with the complex requirements, particularly since the initial broadcast was a global live broadcast to cinema. PhotoCineRent supplied cameras and lenses, Broadcast Rental supplied kit for the gallery, Camalot supplied the fibre systems and EuroGrip most of the grip, with everything curated by SR Films who specialise in high-end multicamera projects across the globe. The SR Films team executed the filmmakers’ technical plans, overseen by technical director Bolke Burnaby Lautier, and producer Simon Fisher and the SiFi team. Technical crew from the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, were supplemented by a few local camera assistants.

Most of the camera crew were trusted operators and assistants Dugdale and Turnbull had worked with on multiple shows – a necessity on a project with a short turnaround on site – with most of the operators travelling from the UK and US. Lead camera operator Nat Hill played a vital role in getting cameras built and placed in the stadium, supported by lead 1st AC Julia Cereijo and head camera technician Yke Erkens. With Turnbull moving onto night shifts for lighting duties, being able delegate responsibility on site to others in the camera team was a key factor.

Many of the cameras were mobile – including manually operated and remote dollies, Steadicams, jibs, towercams (telescopic columns with remote heads) and a four-point Cablecam system for big high wides. “Coldplay shows are typically a joyous explosion of colour and light. Chris Martin is also a very physically dynamic performer and spends much of his time out on a long runway, surrounded by a sea of fans,” says Turnbull, who believes camera movement on a grand scale can also generate a similar exhilaration for a cinema viewer to that experienced by the crowd inside the stadium.

“With such a large stage and performance area, moving cameras fluidly and efficiently is vital. Key grip Jelle Ector did a great job co-ordinating a complex grips package. At times the operators held back on physical camera movement, concentrating on finding relationships between band members, or band and audience. In storytelling terms, capturing the body language and the eye contact between musicians is fascinating. Coldplay are lifelong friends, almost brothers, and you can feel that dynamic in the way they interact. At other points in the show, camera movement became explosive.”

The Venice 2 8K full-frame camera was well suited to the project’s requirements. Starting with the F55, Turnbull believes Sony has always factored in possible “broadcast” uses, for their digital “cinema” cameras, so the interface with OB trucks tends to be quite practical. “In full frame mode, we could simultaneously record 7.6K SLog footage in-camera, while sending out a live HD video signal ready for transmission to cinemas,” he says.

A “dirty” processed picture with LUT and data overlays was used by operators and ACs out on the field, while also being monitored in the OB truck and by Turnbull at the lighting desk, meaning important camera data – such as status of recording, media, power, timecode/sync – plus a live display of current ISO and shutter angle settings could always be seen.

Meanwhile the “clean” Slog/HD output from the cameras, went through individual LUT boxes and then into the vison mixing desk, to be edited live and streamed around the world. In addition to the basic LUT applied to the live pictures, shaders at the engineering control position also had remote control of camera paint functions via broadcast type Sony RCP panels, to fine-tune and match the pictures better – compensating for different makes of lens, and any variance between sensors.

“The panel also gives control of gain/ISO, internal ND filters, shutter angle etc, which needed adjusting at various times in the show. The engineers also had remote control of other camera functions via IP, to trigger remote recording and access deeper menu settings from one central location,” says Turnbull, who worked closely with the DIT and video engineers to create a look they were all happy with for cinema, knowing that for a post-produced version, the director “would still be able to dig back into the 16-bit XOCN 8K recordings (effectively RAW) and grade the footage more creatively, if desired.”

In certain camera positions the crew set the Venice cameras to Super 35 sensor crop mode, to capture tighter shots on telephoto lenses. “On the Venice, that still gives 5.4K (16:9) resolution for post, which is more than ample for a 4K/UHD delivery,” says the cinematographer. “If needing to use extenders or adaptors to get even tighter shots, we could use the Venice 2 dual-ISO function to push the cameras from their default 800 ISO to 3200 ISO, knowing that very little noise would result from that change.”

The Rialto accessory – which makes it possible to change the camera to a split-block plus umbilical cable configuration – was useful in situations where they needed to make the camera body as discreet as possible such as when requiring remote heads on or around the stage.

Dugdale was also impressed by a compact Sony FX3camera that would track 180 degrees around the drums. “It needed to work within the tight footprint of the drums which are surrounded by equipment,” he says. “It couldn’t get in the way of anyone or be distracting on stage and it needed to be easily shipped and within budget. It is my favourite way to capture an artist playing drums and so much more dynamic and exciting than something static which is commonly the case.”

Cinematic experience

Shooting on full-frame cameras made it possible to film with much shallower depth-of-field, compared to live television, which is how most live music is watched. “For a while now many high-end concert films have been filmed on “digital cinema’ cameras with Super 35mm sensors, which immediately gives the footage a more “filmic” look,” says Turnbull.

“Shooting full frame is another significant leap in image quality, and especially in terms of selective focus. On wide-angle lenses, you can not only see the scale of the setting, but still feel very intimately connected to the artist. We were pretty bold about getting cameras right up close to the artists on stage, at carefully selected pre-agreed moments.”

One of the Steadicams was dedicated to capturing scripted shots on stage and cued over headset. An Agito wireless remote dolly was also in the pit and lifted onto the stage at times during the show and cued into action. “This dolly circled the band at close-range on the small B-stage during their acoustic set,” says Turnbull. “It was also used a couple of times to lead or follow Chris up and down the main runway through the crowd and then quickly lifted off the stage and stored in the pit, out of shot.”

Full-frame lenses generally have a more limited zoom range then Super 35mm lenses which in turn have at most half the zoom range of standard 2/3” TV zoom lenses, highlights the cinematographer. “Committing to working within a small and very specific range of shot sizes from each position is a brave decision for a live concert film director, so we consider lensing very carefully. On the plus side, working within those constraints can have a positive effect as it forces the operators to drop some of the habitual ways they might film live music for television. For example, by treating the lenses more as variable primes, and letting the action play out in more considered frames.”

Turnbull also emphasises that cameras like the Venice can withstand more punishment than broadcast TV cameras when it comes to handling very dynamic and varied lighting levels and pyrotechnic effects. “Highlights roll off in a far more pleasing way, and shadow detail allows you to experience the atmosphere of the setting without needing to over-light the crowd. All these factors help create a more cinematic experience.”

Elevating the energy

Two aerial units were used: a DJI Inspire 2 drone flying around the stadium perimeter only (for health and safety reasons), and a helicopter unit that could film directly overhead, as well show the iconic River Plate stadium in relation to the surrounding cityscape.

Having introduced the band to working with FPV drones for promo work the band shot in 2021, Dugdale arranged for an FPV drone to capture wild, swooping aerial shots at close range to crowd and stage, at key moments in the show. He also drafted in Lewis “Doddsy” Dodds – a talented indie action-cam operator who specialises in using an “FPoleV” rig (a long flexible handheld telescopic pole, fitted with a 360-degree POV camera, swung around manually over the audience’s heads).

“The footage from both – used sparingly at key moments – catapulted the viewer to another energy level,” says Turnbull. “Other sections of the show are more focused and intimate such as the semi-acoustic sets the band play on small B and C stages away from the main stage. We treated these in a different way, focusing more on simple framing, and a more documentary style of operating.”

Having been impressed by footage of drones flying through fireworks, Dugdale wanted the team to try to capture the pyro in the same way. “I loved the idea of seeing fireworks from above and then feeling like you’re inside the display,” he says. “And as the stadium venue and stage had no roof it was also possible for our cameras on the ground to be put in a position where the band could be seen in the foreground with the pyro beyond.”

But when working on a kit rich concert Dugdale is conscious to not overuse tech as it can become gimmicky. “Sometimes it feels apart from the whole package and doesn’t gel, so it was important to have some restraint and really pick moments when we felt it becomes effective,” says the director. “The music must inform the tech rather than just using technology for the sake of it.”

Coldplay pioneered the use of LED wristbands for the crowd which flash and change colour when triggered by remote control. “The audience love participating in the spectacle these create, and it brings the whole stadium to life on camera. You can feel the presence and energy of the crowd without always having to light them up conventionally,” says Turnbull, noting the technology has advanced since the first show he filmed featuring them over a decade ago.

“The wristbands can now be activated by infra-red beams projected from moving lights with gobo patterns programmed to timecode. So aside from random chase sequences and colour changes, giant shapes and ripple effects can be created around the stadium bowl – even though the wristbands have been distributed randomly amongst the crowd. The effect is mind-blowing.”

Dugdale agrees audiences are an important part of a Coldplay show and technology such as the wristbands have resulted in “the boundary between where the stage ends and the audience begins becoming more blurred than with other artists. Everyone is part of it, and everyone contributes.”

The filmmaker’s favoured way to show this connection between Coldplay and the crowd is including both in the same shot. To fully immerse the cinema audience in the unique atmosphere of a live event, some angles were shot from the perspective of the audience. “Many camera positions were designed so we would be amongst the audience, and we had a great camera angle that went over Chris Martin’s shoulder straight to the audience, creating almost a dialogue between them. Trying to contain audience and artist in the same shot isn’t revolutionary but for stadium shows especially, finding positions that help show that connection are actually harder to come by than you’d think, but for us they hold great currency in translating the experience of the show, and that exchange of energy between artist and audience.”

As a different feeling needed to be created for each song, when shooting “People of the Pride” – a brutal and aggressive performance in which Martin is even more animated than usual – Dugdale wanted the images to be “more abrasive, steely and hard and to drive a contrast between the verses and choruses”, deciding to shoot the verses in black-and-white and choruses in colour.

A performance with heart

To help immerse the audience further the concert was also screened at cinemas with Screen X theatres which feature additional screens either side of the central screen to offer 270° projection. Three additional RED Monstro 8K cameras with ultra-wide-angle Zeiss 15-30mm lenses were required to shoot content specifically for Screen X.

“We wanted to be sensitive to the content on either side and ensure it was in keeping with what was happening on the main screen,” says Dugdale. “So, the principal film appeared on the centre screen and maybe an audience or a wide pyro shot would be displayed on the left and right.”

When creating the post-produced version of the film, the preciseness of the editing process was crucial and saw Dugdale work with multiple editors to ensure delivery was on time. “It’s an extensive and exhaustive process as there’s a lot of footage to work through and we use Frame.io to go through edit notes and several rounds of changes. We’ll do an entire multi camera pass where I watch everything again on top of the edit to make sure every bit we need is included.”

The director believes a Coldplay production is the perfect concert to capture for the big screen because “it has enormous heart. The audience and their relationship with the band is so important to the show and Coldplay’s production is geared towards it being a communal experience. When concerts are filmed and it’s all about fingers on guitar strings or piano keys, there’s no heart in. You might understand how the music works, but this isn’t a music lesson – it’s about storytelling and emotion.

“So, I film it like I would a dinner party scene in a scripted piece – trying to capture connections. I always tell camera ops I’m not interested in a close-up of a guitar; it needs to include the guitarist’s head because if they are closing their eyes and leaning their head back that’s where the emotion is.”