On Sept. 20, 2016, This Is Us premiered on NBC, introducing viewers to the cross-generational story of the Pearson family.

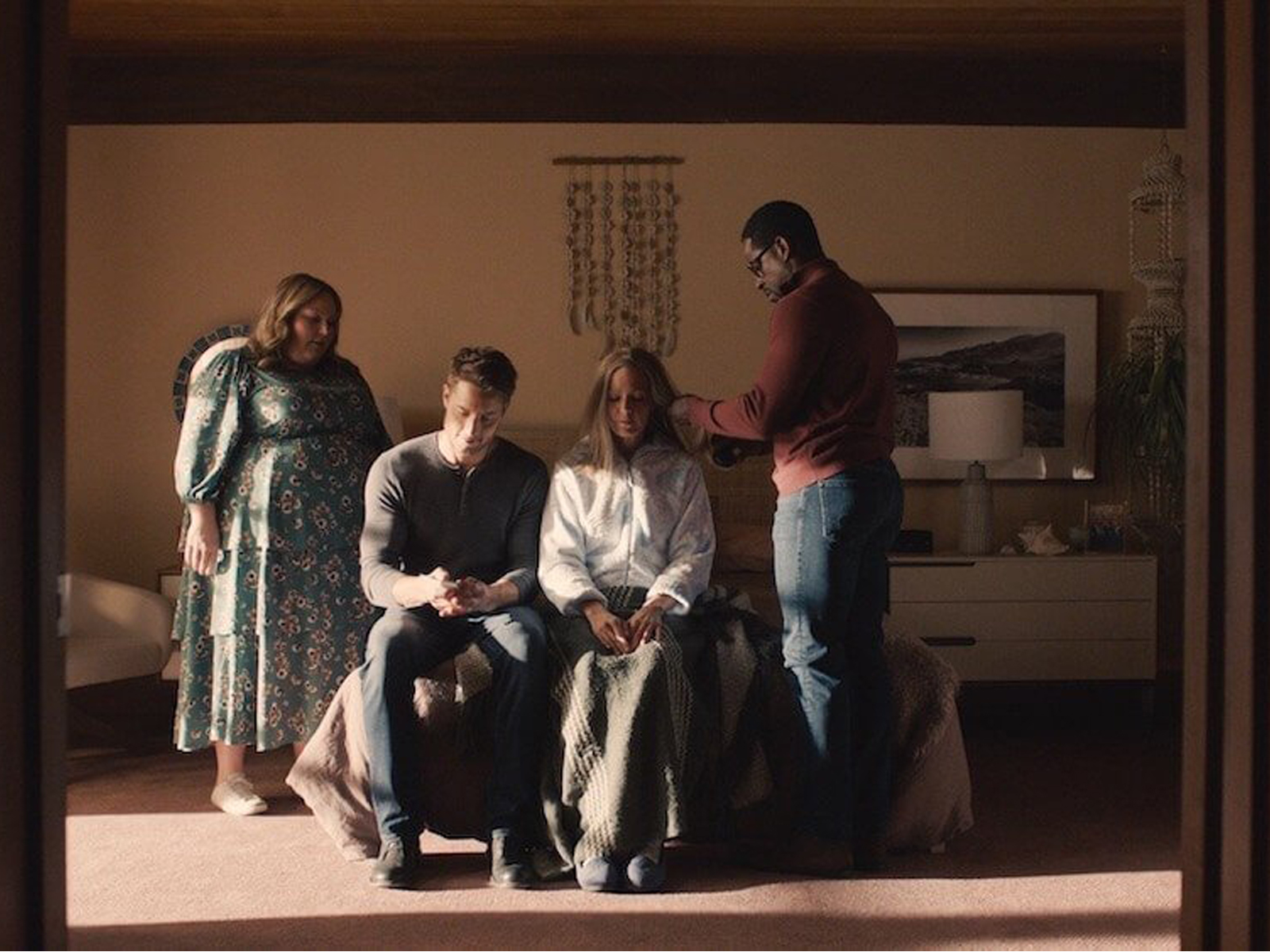

Over the course of six seasons and a storyline that spans as many decades, Jack and Rebecca Pearson (played by Milo Ventimiglia and Mandy Moore, respectively) and their children Kate, Kevin and Randall (played as adults by Chrissy Metz, Justin Hartley and Sterling K. Brown) have captured viewers’ hearts and become part of their lives as if they were an extension of the audience’s own families.

Created by Dan Fogelman, the series came to an emotionally charged end on May 24, closing a significant chapter in the annals of network television and in the lives and careers of everyone involved in bringing the show to life. Cinematographer Yasu Tanida has been with This Is Us since Season 1, having joined when the show was ordered to series following production of the pilot episode, shot by Brett Pawlak. As Tanida prepared for Season 1, he worked closely with Panavision to select his optics package, and This Is Us ended up becoming the first television series to use custom optics — in this case a set of modified Primos.

Panavision caught up with Tanida just before the final episode aired — and just as the cinematographer was finishing his prep for a new pilot — to reflect on his work over the past six years.

Panavision: How did you come to be involved in This Is Us?

Yasu Tanida: I shot the pilot for Pitch, directed by Paris Barclay. Dan Fogelman created the show with co-writer Rick Singer. It was about the first female baseball player in the Major Leagues, and it followed her first week playing for the San Diego Padres. I had a great time filming it, and that’s where I met Dan. He and I are similar in that we both love baseball and are both pretty laid back, so our temperaments get along.

Soon after, Dan asked me if I wanted to do a different series. He had two pilots picked up to series in the fall of 2016, and if I was interested, I could interview for the job. I saw the pilot for This Is Us and was blown away by how interesting and creative it was. I then interviewed with John Requa and Glenn Ficarra, who were the directors for the pilot, and I was lucky enough to be hired.

As you began your work on Season 1, how did you approach building on the foundation that had been established in the pilot episode, shot by Brett Pawlak? What elements did you want to preserve, and where did you see opportunities to evolve or expand upon the visual language?

Tanida: From my perspective as a DP, This Is Us was a great show to join after the pilot because the big reveal was the fact the story took place in two different eras, modern day and the 1970s. Essentially, episode 2 was the beginning of showing those different time periods and opening up what those two worlds would feel like.

In respecting the approach to Brett’s work, I stuck with not shooting the time periods any differently. To this day, even when we go into the future — or episode 617, when we go into Rebecca’s dream state — we apply the same thinking. This helps with editing by allowing the show to cut between eras seamlessly. We also preserved the shooting style of keeping every era handheld and consistent in coverage.

The one change we made when we were starting episode 2 was to choose different lenses. I knew from the beginning that I wanted to create an image that took the digital edge off the screen. There was going to be old-age makeup for Mandy Moore starting in episode 2, so I was running that idea by Guy McVicker [who now serves as technical marketing manager at Panavision Woodland Hills], and we ended up customizing Primos.

What drew you to the Primos as the foundation of your lens package?

Tanida: I’ve been using Panavision Primos for most of my career, and hands-down the main reason is because of how the lenses render faces, which doesn’t get mentioned much. There’s something about the Primos that takes a human face and puts what I see with my own eyes onto the screen — actually, it takes what I see with my eyes and improves on it. The lenses have a way of bringing out the oval shape of a human face and giving it depth on a two-dimensional plane. There are discussions about lens flares, changes of the focus plane, and all the personalities of these lenses, but the simplest reason is that a Primo renders a human face better than any lens out there.

What led to the decision to modify the Primos, and how did you land on the specific modifications you ended up using?

Tanida: I wanted a new look to soften the digital image, and at the same, Panavision had been developing a system to customize lenses that would look consistent from lens to lens. We decided to do a makeup test with some modified Primos. Guy showed me several focal lengths with three levels of modification: medium, heavy and extreme. I remember putting on the extreme 50mm, and it was pretty magical when I looked at Mandy Moore through the monitor. It softened the creases of the makeup without ruining the mids of the image, and it affected the highlights and shadows in an extreme way by glowing the highlights and lifting up the shadows.

We ended up shooting a lot of tests over several weeks with all levels of modification, also testing them at different high ISOs. I then took the camera tests to colorist Tom Forletta at Technicolor Hollywood, and I asked him to take all three modification levels and bring the image back to a normal level, as if the modification hadn’t been applied. The medium and even the heavy could be taken out with modern color-correcting tools, but when Tom tried to take out the extreme look at ISO 1280, something in the image remained — there was still a soft glow in the highlights, the actors’ skin tones had softened, and the shadows had a muddy black-crayon darkness to them. After some more testing and tweaking, an extreme set of lenses were made for us, and that’s basically what we have been using for the last six years — combined with a high ISO and a heavily applied, contrasty LUT — to create the look of our show.

Can you share a bit more about the optical characteristics you saw from the modified Primos?

Tanida: Whenever a 20K tungsten, 18K HMI, a practical on set or even the sun flares the lens, the highlights bloom like crazy and have a certain glow to them. I call it an ‘ugly, beautiful flare.’ It’s not a detailed optical flare, nor is it a rainbow-ish colorful flare. It just halates in an ‘ugly, beautiful’ way.

Then the mids, where we keep most of the skin tones, has a softness to it. The extreme modification is more forgiving with the old-age makeup and takes away blemishes. Walls, doors and lines in a frame soften as well.

And the shadows end up becoming very muddy, with a texture that I can only describe like black crayon that’s been colored in over and over. Also, with the 1280 ISO and the LUT, there’s a digital noise that comes alive in the shadows and that I feel goes hand in hand with the romantic and nostalgic aspect of our show — hopefully!

Within your lens package, were there any particular focal lengths that proved to be favorites over the years?

Tanida: The main lenses were usually the 35, 40, 50, 65, and 75mm. I would say 95 percent of the show was shot on those. When we want to do a super-close push-in, or when we want a flare that has some color and streak to it, we like to use the 50mm Macro handheld.

Do you remember what project first brought you to Panavision?

Tanida: I actually can’t remember the first project, but I do remember walking into Dan Donovan and Cathy Pierce’s offices to get to know the gear at Panavision Hollywood. I think I knew Akira Kurosawa shot his later films using Panavision, and I wanted to see for myself. There’s also a beloved Japanese series of films of this guy who is basically the Charlie Chaplin of Japan, named Tora-san. His films were always shot in widescreen anamorphic Panavision, so that’s etched in my memory.

I remember Mike Carter having a desk outside Cathy’s office as her assistant, and now he helps me with my current projects. I remember Tak Miyagishima helping out a fellow Japanese American, showing me the lenses he built at Panavision Woodland Hills many, many years ago.

There are many reasons I’ve kept coming back to Panavision over the past 20 years. I had a perception of the cinematic feeling Panavision gives, and that hasn’t disappointed me. Like I mentioned, the quality of the lenses is top-notch. The customer service and knowledge of their equipment is always helpful. When we need to accessorize a third or fourth or fifth camera, they are a solution-first company. And just like This Is Us, Panavision has become part of my film family and a big part of my career as a cinematographer.

Over the course of shooting This Is Us, have you found inspiration in any particular visual references?

Tanida: Over the first four seasons, I was subconsciously shooting what I felt was right for our show. Then, during the six months off in 2020 due to the pandemic, I had the time to think about what made the look of our show. I realized that the Dardenne brothers’ films were a big influence early in my career, and I gravitate to that style of filmmaking in general. Going back even further, I had done a film in 2007 called August Evening that received an Independent Spirit Award, and the director and I used the Dardennes as our inspiration. I think it carried over all these years to This Is Us.

Part of the Dardennes’ style consists of all handheld, but not aggressive handheld that draws attention to itself; natural lighting, but I’d say ours is a touch more stylised, with hard lighting at times; and, most importantly, the idea of giving the focus of every shot to the actors. There are many techniques in filmmaking: dolly moves, cranes, zooms, framing, use of color, etc. The thing with technique is that it can sometimes call attention to itself, and the problem with calling attention to the technique is that it can end up carrying the most weight on the screen. The viewer has a finite amount of attention, and if technique attracts that attention, the viewer gives less attention to characters, their plight, how a character is like them, etc. In a nutshell, I want that focus to be on our cast. I think the Dardenne brothers do a good job of that.

What was your process of working with the camera operators to define and refine the show’s subtle handheld camerawork?

Tanida: I think it’s a very difficult job being a camera operator on This Is Us, and the ones who have had success on our show are very similar in their disposition. The first attribute they share is they are rock-solid holding the camera, whether it’s a 35mm, a 65mm or a 100mm. We never want to draw attention away from the performance. We work on that from day one. When they can hold a frame solidly, then we begin introducing movement. Eventually, they need to be able to walk backwards with a 50mm like the camera is part of their body. We talk about controlling their breathing, using their body to control the camera on their shoulders, and focusing on keeping the horizon level throughout every shot.

The second attribute is the feeling they have about panning or tilting — how slow or fast that move should be and, most importantly, when to do that action. After a take is done, I go over and speak to them about where we could have done something different. Most of that conversation pertains to the story. We don’t use headsets because I want them to have their own voice in deciding what to do. I want them to grow on their own terms as operators of our stories.

Third, it involves matching frames on coverage. We try to match the shot sizes of our coverage unless we mean to give someone a tighter close-up. The idea behind matching frames is to be objective with each character — shooting evenly, at eye level with everyone. In my opinion, that idea gives every character a level playing field.

I remind operators they have to stay sharp and focused on those mundane two-hander scenes, to keep alert and follow the dialogue and story. If they can stay alert and vigilant on those mundane scenes, then, when the really emotional scenes come up and they have to decide whether or not to push in, it will come to them naturally. And it does.

I was lucky to have amazing operators, and as soon as we got on the same page, I barely had to tell them anything. James Takata, James Goldman, Coy Aune, Daniel Cotroneo, Beau Chaput and Colby Oliver have all been a part of the This Is Us operator family.

Who have been some of your other key crewmembers over these past six seasons?

Tanida: I couldn’t have done the show without Sean O’Shea, our A-cam 1st AC throughout all six years. Our B-cam 1st AC Richie Floyd and Season 6 1st AC Joe Solari are both amazing at pulling focus. Also our longtime 2nd ACs Brian Wells, Jeff Stewart, Wade Ferrari, Hunter Jensen, and Tim Sheridan, and our loaders and digital utilities over the years, Gobe Hirata, Mike “Mad Dog” Gentile, Emily Tapanes, Maeve Gilleran, Jimmy Grob, and Adam Garcia.

You’ve spent six years shooting 104 episodes of a show that’s left an indelible mark on the popular consciousness. What does it mean to you on a personal level to have been part of This Is Us and now for the series to be concluded?

Tanida: It’s bittersweet finishing a project that’s been part of your life for six years. In TV, you rarely know if you are coming back for another season, but during Season 3, we were renewed for the final three seasons, so we were fortunate to know when the end would be.

I feel very lucky to be a part of this show and to have worked with such an amazing cast not only in front of the camera but off of it. There was so much laughter and camaraderie on the set every day for all six years. Our crew got along so well, and I will remember them for the rest of my life. Our A-cam 1st AC Sean O’Shea says it’s the best show he’s ever worked on. I think we made the best of every shot, didn’t take any moment for granted, and made a show that, like you said, hopefully ‘left an indelible mark on the popular consciousness.’

–

Photos and frame grabs courtesy of Yasu Tanida and NBC. This article has been shared with permission from Panavision.