People Love Dinosaurs

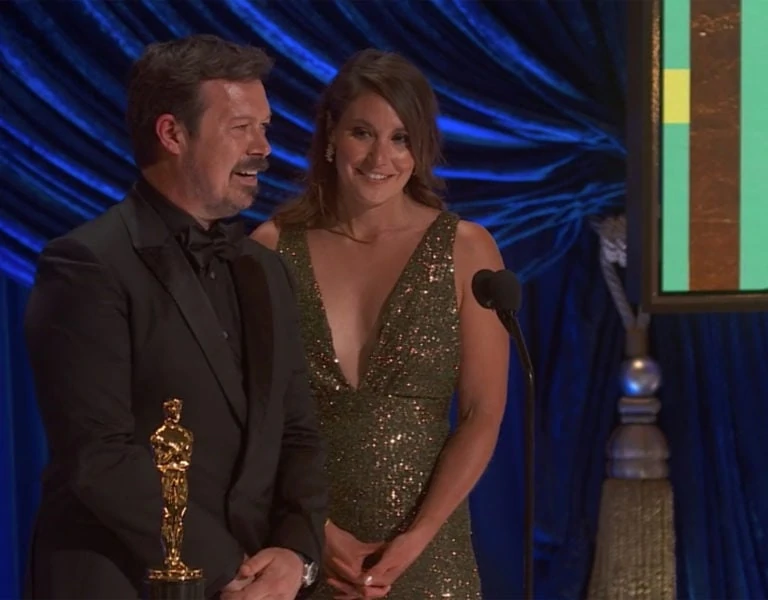

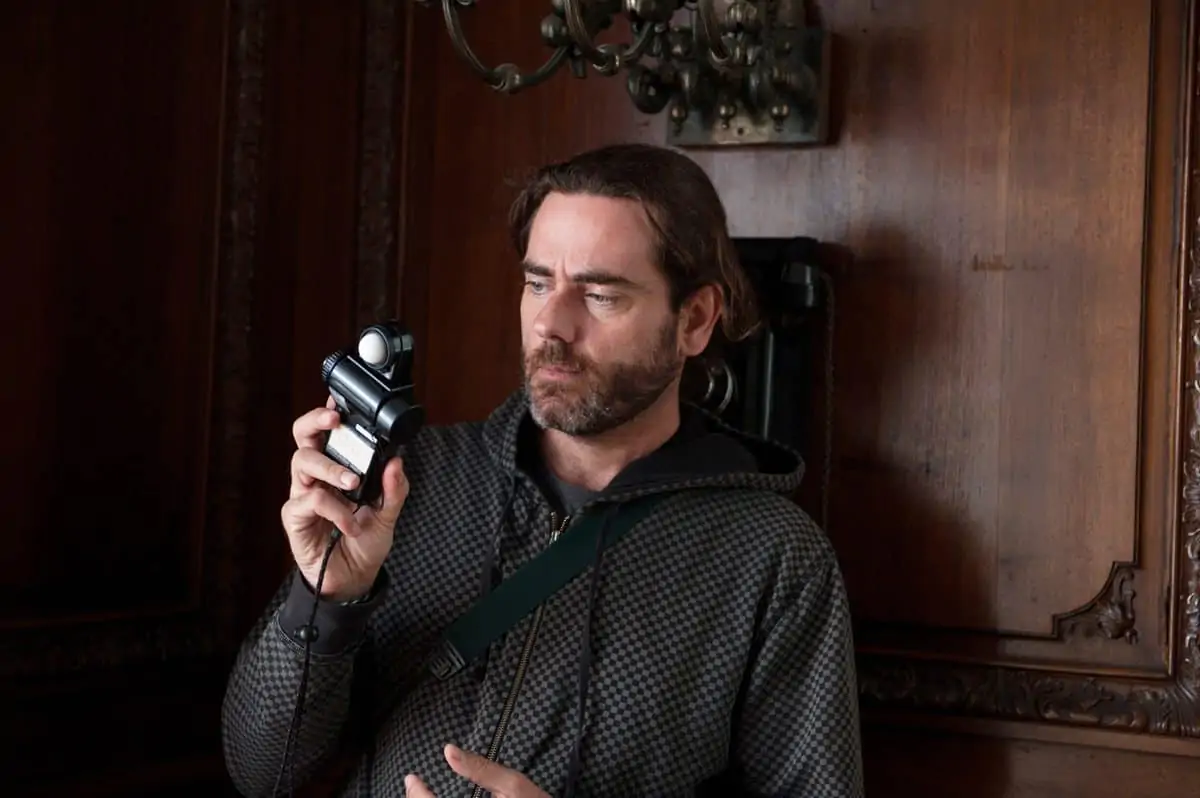

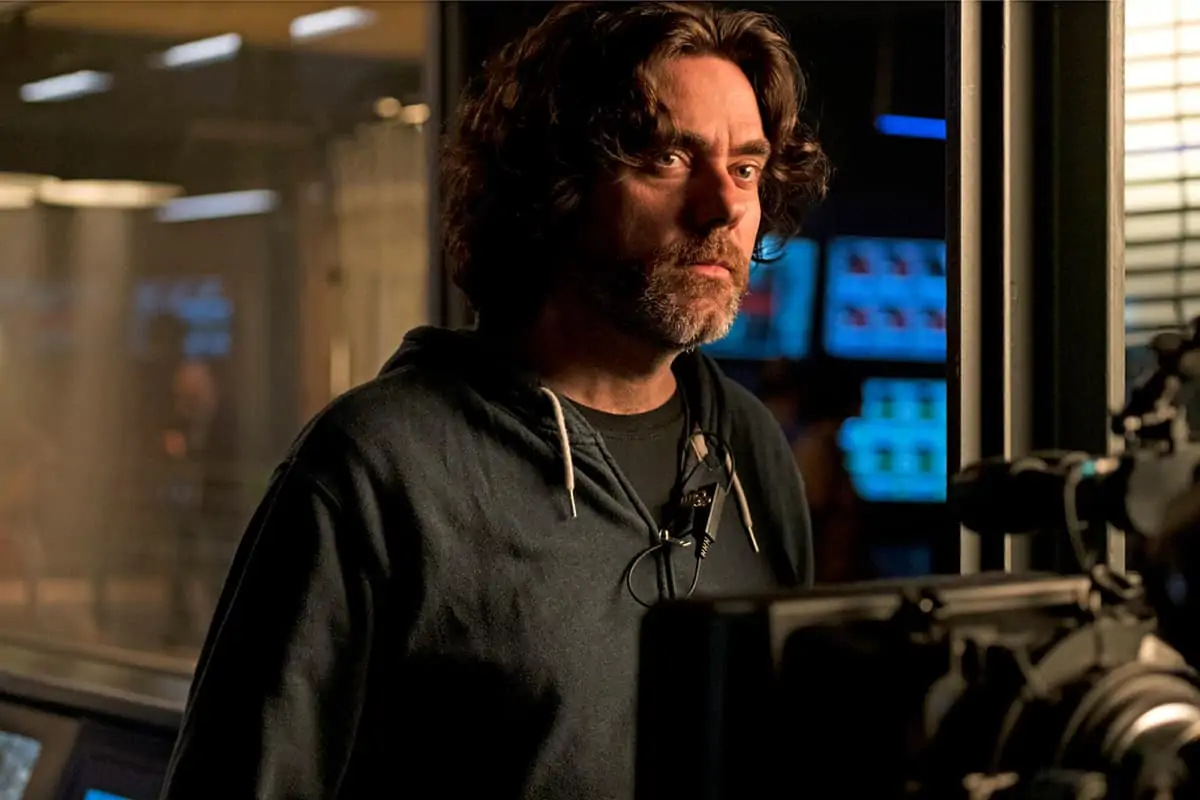

Oscar Faura / Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

People Love Dinosaurs

Oscar Faura / Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

Directed by J. A. Bayona, and executive produced by Steven Spielberg, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom marks another action-packed addition to the blockbuster dinosaur franchise. Made on a budget of around $170m, the fifth instalment of the Jurassic Park series, and the second instalment of a planned Jurassic World trilogy, had grossed over $372 million worldwide at the time of going to press, making it the ninth highest-grossing film of 2018.

Set three years after Jurassic World (2015), the volcano on Isla Nublar begins roaring to life, and scientists must rescue the remaining dinosaurs from this extinction-level event. We caught up with cinematographer Oscar Faura to discover more about his work.

How did you come to get involved with the production?

OF: J.A., the director, offered me the project. It was our fourth movie together, after working on The Orphanage (2006), The Impossible (2012) and A Monster Calls (2016). It was bigger than any other project I had shot before, but I felt excited to be part of a project lead by Steven Spielberg and directed by my film schoolmate.

How did you envisage the look of the film?

OF: J.A. had a very clear idea that it should look like a classic adventure movie. The peculiarity this time was that, at a certain moment, the script had a twist towards a different genre. The second half of the story had some hints of mystery and even horror. That’s a terrain we both felt very comfortable with. The challenge was to make it suitable for all audiences, but still keeping the strength of a gothic story look.

What creative references did you look at?

OF: During the early preparation a team of concept artists designed a thorough palette of key images, under the supervision of the production designer Andy Nicholson and J.A.. That was a very important guide for all the departments to follow. All those pictures were like a visual timeline of the movie, and that was very helpful to unify the different criteria during the preparation and the shoot.

Obviously, we also had the previous movies of the franchise as starting references. There were some iconic elements that we took into consideration, like aerial shots approaching the island and the rainy scenes at night, which are the essence of the Jurassic legacy.

"J.A. Bayona is a director who puts a lot of attention and dedication to the camera work. He uses the camera to tell the story, not just as a witness but also as an additional character. I would define the camera style of the movie as classic and composed."

- Oscar Faura

Where did you shoot?

OF: Principal photography was in England and Hawaii. We shot on stage at Pinewood Studios. We also had some smaller sets built at a warehouse in Langley, near Pinewood, and in Minley, were we built the mansion. In Hawaii, we shot day exteriors in different locations at Oahu, such as the Kualoa valley where we shot the dinosaur stampede, and He'eia Kea Harbour, where we shot the dock destruction scene.

Tell us your reasoning behind your choice of cameras, lenses, lights and grip?

OF: Before making the final decision, we did side-by-side tests with different cameras and lenses. We tested digital and film cameras, spherical and Anamorphic lenses, from different manufacturers. The fact that the movie was going to be projected at IMAX theatres was an important consideration, so we finally chose the Alexa 65. It was my first contact with a large sensor digital camera. We tested different vintage large format lenses from ARRI and Panavision and I finally decided to go with Sphero 65 lenses from Panavision.

Give us some details about your lighting and grip kit?

OF: LEDs were the main type of light source on the movie. We used big arrays of SkyPanels in some of the biggest sets, like the Diorama Room, the interior of the Arcadia ship, and the glass dome rooftop of the mansion.

My gaffer Lee Walters, provided a wide selection of handcrafted RGB wifi LED light fixtures that we used to light close-ups on the actors. We had different sizes and shapes and they were incredibly lightweight. It was funny because all those different lights were totally new for me and we had to learn their names. The “Pizza Box” was a 3’x3’ square, “The Coffin” was an 8’x2’ rectangle, “The Shield” was a 4’ circular light. My favourite one was an 8’x4’ light that I called “My Beloved”.

The grip equipment was very diverse. On stage, two dollies and a Technocrane composed our basic kit. We always had a Libra head with us to use on the crane and very often on the dolly too, especially when we were moving without tracks over a “dance floor”. In Hawaii, when shooting the exteriors, we added tracking vehicles to the basic kit, to be able to shoot in the rough terrain of jungle or the volcano valley – including an Edge Arm, and the Polaris RZ 1000, among other camera supports.

Where did the kit come from?

OF: The camera equipment came from ARRI London. They supplied six ARRI Alexa 65s, three for first unit and three for the second unit. We also had an ARRI Alexa XT for a few slow-motion shots, and an Alexa Mini for the underwater work.

Lenses came from Panavision. We got four complete sets of Panavision Sphero 65 lenses. We also used the Panavision Primo 70 zooms, mainly in Hawaii for the aerials shots. Our lights came from Pinewood MBS in London.

Who were your crew?

OF: The crew was excellent – all very skilled and hard workers. Lee Walters (UK gaffer) and Josh Davis (US gaffer), Andy Munday (desk operator), Francesco Giardiello (DIT), Ian Fox, Pete Cavaciuti and Maceo Bishop (camera operators), Guillem Huertas (focus puller), Tomasso Mele (UK key grip) and Jerry Deats (US key grip) all did an excellent job. Their experience and their teams were all very supportive, and I feel very lucky to have had all of them on the project.

What was your approach to the camera movement?

OF: J.A. Bayona is a director who puts a lot of attention and dedication to the camera work. He uses the camera to tell the story, not just as a witness but also as an additional character. That is translated to a specific way of working on-set. We worked mainly with one camera. I would define the camera style of the movie as classic and composed. The dolly was our main camera support and we just used handheld or Steadicam occasionally.

We had different ways of designing the scenes. When working on a VFX scene, it was previsualized, and the framing and lenses were defined during the process. When it wasn’t a previsualized scene, we normally did a very basic photo-shoot on-set, while the sets were still under construction, so we could define what was needed for any of the scenes. We didn’t improvise much, even when we were shooting non-VFX scenes as everything was prepared in advance.

"One of the biggest and more complex sets to light was the Diorama Room. We had day scenes and night scenes and a blackout scene in the same space, so we had to prepare it carefully to make it versatile."

- Oscar Faura

And what was your approach to the lighting?

OF: The lighting of the movie had two very different parts: shooting on-stage in the UK and the exteriors in Hawaii. In England, we shot mainly on-stage and mostly at Pinewood. When you’re on-set, you have full control over the lighting, but you have to start from scratch and make it look right and realistic.

One of the biggest and more complex sets to light was the Diorama Room. We had day scenes and night scenes and a blackout scene in the same space, so we had to prepare it carefully to make it versatile. The Diorama room was designed with a glass dome on top of it so the lighting design followed that idea. The glass dome was CGI, so we had an open ceiling on-set where we placed three 30’x30’ light boxes with SkyPanels to mimic the soft light coming through the dome. We also had SkyPanels surrounding the perimeter of the ceiling so we could shape the space and the characters from the sides. Outside the windows, we had ARRIMAXs for the day scenes and we played with smoke to create light shafts. That’s a constant in the daylight scenes of the movie shot on-stage.

The interior of the bunker was shot on stage too. The abandoned bunker ceiling had some cracks that we used to create light shafts. The most difficult part to light came when the lava from the volcano was leaking into the bunker through the cracks, blocking the sunlight and creating a light and colour transition. To create the effect, we worked with Paul and Ian Corbould, from the SFX team. They built a system that allowed us to throw flames from the ceiling in a controlled way. We also had LED Sun Strips on towers, synchronised with the flames, so we could cast the light of the lava falling on the actors’ faces and on the walls. Digital lava was generated and overlaid to the flames in post.

In Hawaii, we shot mainly day exteriors and the challenge was to control the sunlight and keep it constant. This time the island was under the menace of a destructive volcanic explosion and the park was abandoned and in ruins. So I tried to visually describe how the volcanic activity was affecting the environment.

When they reach the island by plane, it looks majestic. They land in a sunny and tropical place, but as they get closer to the volcano, and the mission gets trickier, the sun disappears under the ash cloud and turns into a gloomy place. We did a lot of negative lighting during the stampede at the volcano valley scene, placing huge black frames over the actors to enhance the effect of the ashes and smoke coming from the volcano.

Is there a scene in the movie that you are especially proud of?

OF: There’s a scene at the Diorama room where the three heroes, Owen, Claire and Maisie are trying to escape an Indoraptor in the dark. The lights of the dioramas are still lit but the space is pretty dark. They round behind a Triceratops skull-base, trying to hide from the monster, and there’s a beautiful crane movement going up that describes perfectly what is happening from the top.

When the camera moves from a low angle to a top shot angle, the lighting set-up that works perfectly for the first camera position becomes flat lighting when the camera is facing down. We managed to do an invisible light crossfade that kept the ambience.

They try to escape through the diorama. Owen decides to switch-off the lights so they are not exposed to the Indoraptor hidden in the blackness. They cross the diorama in the dark. Suddenly the light accidentally comes back on and the glass of the diorama creates a mirror effect from the inside. They just see themselves reflected, but the Indoraptor is on the other side of the glass watching. It was an amazing scene to shoot from a photographic point-of-view.