SPECIAL OPS

The team behind short film Fireworks explain how they used virtual production technology to explore new ideas and immersive storytelling.

Fireworks is a short political thriller about MI6 agents in a special operations room in London attempting to eliminate a dangerous militant in Tripoli. Helmed by VFX house DNEG’s creative director Paul Franklin and backed by Epic Games, the film uses virtual production technology to cinematically realise the moral dilemma at its heart.

The script by Steven Lally was originally set purely in the ops room, with Tripoli off camera. Its development took a detour when it almost became an immersive VR project, at which point the possibilities of seeing the events in the Libyan capital were explored. “I realised that we could return to the idea of making Fireworks as a film,” says Franklin, “using the LED virtual production approach to explore the new ideas revealed through our experimentation with immersive storytelling.”

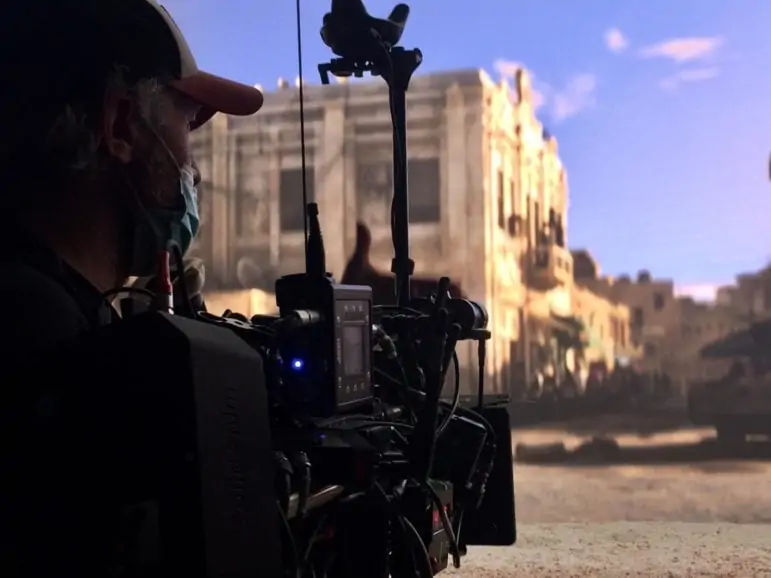

It was decided that, at a key point in the story, one wall of the ops room – a practical set – would dissolve away to reveal the Libyan street, a virtual background. Production designer Jamie Lapsley based the street on a real Tripoli location, and a virtual art department at production partner Dimension Studios realised it in Epic Games’ Unreal Engine.

A bespoke LED volume was constructed at 80six (another production partner) using both ROE Diamond and ROE Carbon panels. The former, with a brightness of 1500 nits and pixel pitch of 2.6mm, comprised the in-vision wall, a curved 18×4.5m surface; the latter, much brighter at 5000 nits but with a blockier pixel pitch of 5.6mm, formed ceiling and side panels for interactive light. “One of the side panels crept into a few shots without us noticing as it was very much out of focus in the background,” Franklin reveals. “It looked fine, so the shots are in the film!”

Cinematographer Ollie Downey BSC joined Fireworks at the last minute after another DP had a scheduling conflict. “Coming onto the project quite late and because we didn’t have the budget of a bigger show, testing was restricted to a day on the set the week before, so we had to learn as we went to some degree,” he explains. “All of our research had pointed to the Alexa as being the camera to use. We didn’t use any filtration on the lens. Our test day had shown that haze on set would help match the foreground contrast to the contrast on the screens and tie the two together.

“Paul Franklin has a great eye for the cinematic – as you would expect from a man with his list of credits – and was keen to reference classic thrillers for the London section of the story,” Downey continues. For this reason, the filmmakers chose T Series anamorphic lenses, which were supplied along with the camera by Panavision London. “Kirstie Wilkinson, our contact there was incredibly supportive.”

Franklin and Downey conducted a recce in virtual reality, with the practical ops room set rendered in 3D alongside the Tripoli street. “A great experience!” Downey enthuses. “Being able to change lenses and line up shots in advance was invaluable.” With space for the physical set at a premium, the filmmakers were able to spot potential problem areas in advance and re-block where necessary.

Franklin was involved in the lighting of the virtual backgrounds. “The process is very familiar to me from my years as a CG artist and VFX supervisor,” he explains. “I would encourage all filmmakers who want to work with the technology to educate themselves about this part of the process – it’s very much worth it!”

Downey approved of the results. “The back three-quarter sun position at a low angle was exactly where you would want it, and the atmospheric diffusion was lovely.”

On-set lighting was a collaboration between Downey, gaffer Jonathan Spencer, board op Andy Waddington, and lead Unreal artist Craig Stiff. “This is somewhere that more prep would have certainly helped,” Downey admits. “Whereas on set we are used to working in certain values, they didn’t necessarily correspond to Craig’s setup. It was a good team effort though and Craig did a great job of translating all the strange terminology that we were throwing at him on a daily basis!”

To match the light quality of the video wall, Downey used LED sources including ARRI SkyPanel S60s to illuminate the foreground. “Overall, though, the less you do, the more believable I think it is,” he remarks.

Fireworks was generally shot on wider lenses, “although it was the slightly longer lenses that really worked well on the volume,” the DP notes. “When we could get back as far as possible from the wall and line up a close-up on a 50mm the background felt incredibly believable.”

Real-time camera movement data was captured by an EZtrack system and fed to Unreal Engine to render the correct perspective on the screens. “Handheld really showed the wall off well, especially when you had shifting parallax,” says Downey.

“LED volumetric virtual production is a hugely powerful new way of working,” Franklin reflects. “We’ve really only just scratched the surface of how to use it.” He advises any filmmakers considering the technology to get the biggest, highest-resolution LED wall possible, and test extensively. “Have backup and contingency plans for everything,” he adds.

“I think Fireworks was the perfect script for the volume,” Downey concludes, “as it wasn’t written to showcase virtual production and it wasn’t a choice based on budget or travel restrictions. The volume was a clever solution to telling the story visually.”