EMOTIONAL JOURNEY

Guided by the emotions of Swan Song’s central character, cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi and director Benjamin Cleary create a visual style to suit a poignant, family-focused tale set in the near future that today’s audience will find relatable.

Struggling to come to terms with the terminal illness that will cruelly cut short the time with his loving family, Cameron (Mahershala Ali) is presented with a solution that could protect his wife Poppy (Naomie Harris) and son from heartache. In writer-director Benjamin Cleary’s Swan Song – a tale of love, loss, and sacrifice set in a near future – Cameron grapples with the heart-wrenching dilemma of whether to duplicate himself without his family knowing, leaving his replica to continue on his life’s path.

When defining the visual techniques to use to immerse the audience in the emotionally charged narrative, it was important for Cleary that the film was not set too far in the future. It needed to be relatable and recognisable to the audience and “something close to our world today.”

“I never wanted to go too far with the sci-fi because it was all about the human story, the love story, the family,” he says. “I wanted to create something that never felt too far removed from today’s tech, so all our aesthetic choices were made with that in mind, staying as subtle and understated as we could.”

Having read Cleary’s script, cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi (Silver Lining Playbook, Warrior) could easily place himself in the protagonist’s position and relate to the story as he also has a wife and son of similar ages to Cameron’s.

Cleary’s strong ideas about the direction the film needed to move in were of great benefit to Takayanagi’s creative process. “When the director has a clear vision, the flow begins naturally,” says the cinematographer. “This vision was really guided by Cameron’s emotional journey.”

During the two-month pre-production, they analysed the script in detail, discussing the emotional flow and working through Cleary’s extensive storyboards, creating shot lists, and always keeping the story as the focus. “Masa loved to analyse the script with me, over and over, delving into the story beats and emotion of the film, gleaning insights together into what motivated the characters and what feeling we wanted to create, scene by scene and overall,” says Cleary.

Through this narrative-focused preparation, Cleary felt he and Takayanagi started to operate on the same wavelength. From there, they organically began to discuss the visual style. “We were absolutely making the same film and all of our creative decisions were made in service to the story,” says Cleary. “When you have a strong foundation like this, it becomes easier to know which creative decisions feel like part of the coherent, purposeful vision.”

Cleary was also impressed by the respect Takayanagi showed him as a first-time filmmaker. “You worry a little, making your first feature, that a well-known, excellent DP like Masa who has shot so many great films, will come in with an ego, but he never had any of that,” says Cleary. “He supported the vision and added to it every day and I never had to battle for what I wanted. Our conversations always felt like they bore fruit. Masa is a great artist; watching his work support the wonderful performances by our cast was a gift every day on set.”

Supporting the story

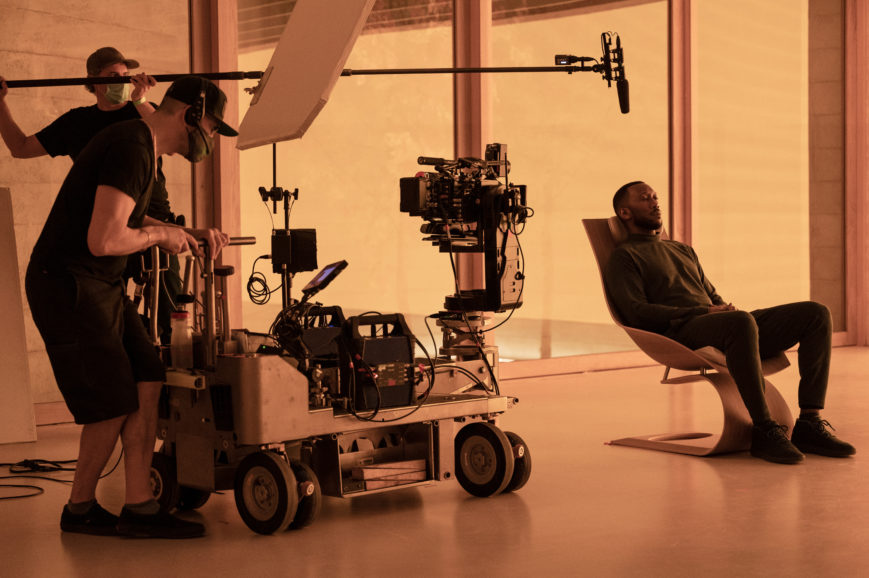

The filmmakers needed to distinguish between Cameron’s life at home and his time at the futuristic labs where he would first meet his clone Jack and Dr. Jo Scott (Glenn Close). One half of the two disparate worlds, the present-day scenes in the lab and at Cameron’s house, would be composed and calculated, using a dolly and Steadicam. In contrast, the flashback sequences would be “loose, spontaneous, and free”, and almost always captured handheld.

“We wanted the handheld scenes to represent the memories that Cameron can take with him. But there is an exception to our rule towards the end of the movie when Cameron returns to the house for the last time. Even though it is not a flashback sequence, we switched to handheld part way through that sequence to convey that Cameron had found peace within himself, so that handheld footage would also become a memory for him,” says Takayanagi.

Production designer Annie Beauchamp also helped develop the worlds supporting the story, incorporating a futuristic feel when needed. “The art department did an amazing job,” says Takayanagi. “Annie and I went through ideas about which lights would be installed in the sets, and we tried out some concepts using 3D models to explore them virtually which was very helpful.”

Extensive tests with VFX supervisor Ajoy Mani were also carried out in prep to explore how to approach the scenes featuring Cameron and Jack in the same frame and what enhancements might be needed for the sequences in the lab that incorporated the LED wall.

Principal photography on the three-month shoot then began in November 2020. The lab basement was captured on stages in Vancouver and the rest of the movie was filmed on location around Vancouver. Stunning aerial footage of the Vancouver landscapes also helped set the scene for sequences at the lab, captured by chief drone pilot Patrick Weir at Peacemaker Filmworks in Vancouver.

“All of the crew in Vancouver were so helpful and hardworking in helping capture the story, including Steadicam operator Peter Wilke, 1st AC Dan Morrison, key grip Kim Olsen, and dolly grip Darin Wong, to name a few,” says Takayanagi.

In line with the poignant story, lighting needed to be as soft as possible. Gaffer David Warner suggested using LED lights, predominantly ARRI SkyPanels, and fixtures which could be installed into the sets, dimmed, and coloured as needed. The colours of the LED wall, provided and controlled by G Creative in Vancouver, were chosen to link in with the emotion of each moment.

“We didn’t want the lighting to be the focus of the story. It was important for us to be very subtle, so we tried to make the set as soft as possible,” says Takayanagi. “In terms of the natural light we used for exterior scenes, Vancouver winter is primarily cloudy or rainy, so it was very consistent.”

Due to the pandemic, Takayanagi could not visit the lab at Company 3 every day to view dailies, so he used a ClearView system to view them remotely. Every evening, using a calibrated monitor in his apartment in Vancouver, he collaborated with dailies colourist Jaan Spirka to carry out real-time streamed colour grading.

As the cinematographer was already in Pittsburgh for pre-production on a different project when the final DI session took place in New York, he was unable to join. Cleary and Company 3 chief creative officer and senior colourist Tom Poole supported Takayanagi’s work by creating a fairly bold grade which still felt rooted enough in realism.

“Tom’s work was stunning,” says Cleary. “For the more visually adventurous ‘sci-fi’ moments, we weren’t afraid to push things into a more heightened place because it felt like that was part of Cameron’s subjective sensory experience. That was always our compass. We also wanted to support the two shooting styles with two subtly different colour treatments in the grade.”

Separating the shooting styles

Whether it be freeform flashbacks or clinical lab scenes with a more futuristic edge, Takayanagi captured the beautifully poetic story using the Alexa Mini LF, supplied with the lens package by ARRI Rental. Chosen due to his familiarity with the camera, the cinematographer values the Mini LF’s “natural and honest colour.”

From pre-production to final grade, Swan Song’s contrasting worlds of treasured and triggering memories and present-day emotional turmoil were frequently the focus of creative discussions. As Cameron struggles to accept his time is running out and then begins to make peace with his ultimate decision, the film shifts in tonality and filmmaking technique.

One scene sees Jack being questioned, almost interrogated, by his replica Cameron and Dr. Scott about the death of Poppy’s twin brother and a painful recurring dream that has haunted Cameron. Jack speaks of fond memories and then the film darkens tonally as he is forced to revisit more painful memories from his and Cameron’s past.

Cleary admits that this midpoint in the film – a shift in the balance or mindset of the protagonist – was one of the most challenging scenes to write and direct. “What begins in the movie as a thorough examination by Cameron to see if Jack is an authentic version of himself, slowly evolves over the course of the film into a self-examination by Cameron. This is a turning point in that evolution.”

Dr. Scott and Cameron ask Jack very personal questions to test his authenticity before the film dips into a fond memory, that of Poppy receiving a piano for her birthday from Cameron and her brother. “This is a great example of the two shooting styles we employed in the film,” says Cleary. “For present day, we’re often locked off or symmetrical and composed, slow push ins with considered, purposeful framing.”

The primary glass relied upon for the present-day sequences was a set of ARRI Master Anamorphics. “The lens series was expanded for the full frame sensor of the Mini LF by the amazing team at ARRI,” says Takayanagi. “Matt Kolze in Burbank and Sarah Mather in Vancouver were incredibly helpful during the customisation process.”

Cleary feels the anamorphic lenses employed in the scene with Dr. Scott, Cameron, and Jack, were the ideal choice when shooting the centre-framed sequence, with the slow push ins on Cameron and Jack. “Present day needed to represent Cameron’s emotional, stuck experience. However, for brief memory snippets we created a different look and feel, shooting with spherical lenses. It was all handheld and largely improvised based on scenarios I would write with back story details for the actors, to catch beautiful spontaneous moments,” he says.

“As Masa operated, he was involved in a kind of intimate dance with the actors, so it felt immersive and subjective, more like the texture of memories. His ability to be there as a participant in those improvised scenes and completely in flow with the actors was wonderful.”

ARRI DNA LF lenses were chosen for handheld flashback sequences and some of the film’s final scenes, with Signature Primes used for the “contact lens” camera footage. “The DNA LF lenses are a little softer and have a kindness to them, which I associated more with memories,” Takayanagi explains. “Whereas the Signature Prime was well suited to the contact lens camera footage because it’s such a superior lens from edge to edge.”

For Cleary, the scene in the lab featuring Cameron, Dr, Scott, and Jack demonstrates how the present and past cut together and Swan Song’s contrast of styles. “As we cut back to the lab from a memory, it looks and feels completely different to the memory we have just been immersed in. As this scene progresses, the questions for Jack become more personal and difficult, as Dr. Scott keeps pushing Jack about the aftermath of Poppy’s brother Andre’s death,” he says.

The director’s favorite part of the scene follows – a “very long, slow, centre frame push in on Cameron and as the questioning intensifies, Cameron answers the question himself, lost in the moment.” It’s a shot Cleary believes few actors could withstand in the way the talented Mahershala Ali does. “I wanted it to be uncomfortably long,” he says. “We’re centre framed, slowly pushing in on him as the off-screen questions crash against him in waves. It’s about being totally immersed in Cameron’s subjective experience.”

The filmmakers then framed Jack identically so when they cut between them, “the two characters dissolve into one another.” Style supported their themes, and the lighting was also integral to the scene. “We put Cameron in silhouette to support the mood and as the scene progresses, we support the shift in tone by transitioning the lighting in the room to a dark blue,” says Cleary.

“And blocking wise, Dr. Scott sits antagonistically between the two men. The scene took a lot of planning with Masa and our wonderful crew. I’m proud of it. Every element is working as I wanted it to. It’s a credit to my whole team and of course to our extraordinary actors who put so much trust in me.”