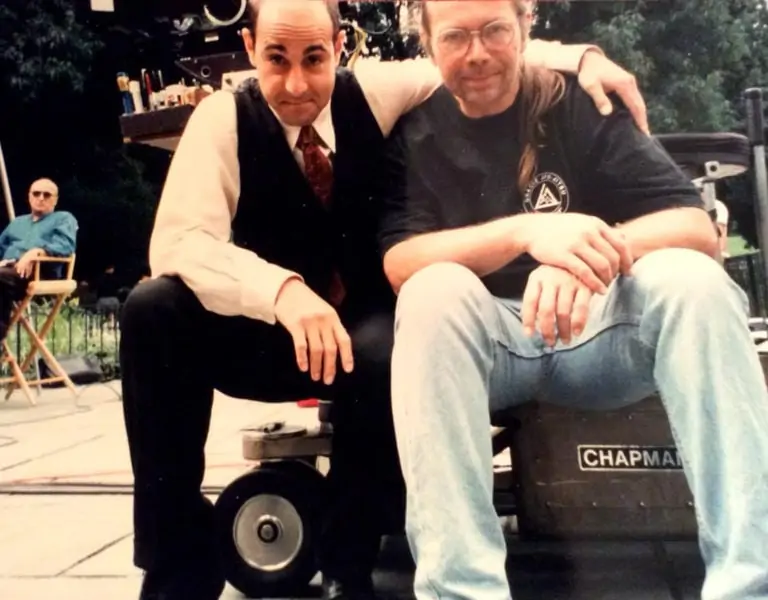

Karen Pyudik talks to Ken Kelsch ASC about his collaboration with American filmmaker Abel Ferrara, his filmmaking philosophy and inspirations, and his lensing of films such as Bad Lietenant, Welcome to New York and The Addiction.

Born in Brooklyn, Ken Kelsch ASC lived most of his childhood in Northern New Jersey. He enlisted in the Army after dropping out of Rutgers University and was selected for the United States Army Special Forces (GreenBeret). Kelsch served in Vietnam between 1968-69 and left as a first lieutenant. After graduating from NYU in Film & TV in 77, Kelsch went on to shoot Driller Killer in 1978. Since then he has shot more than 30 features, numerous commercials and pilots, along with more than 100 hours of network TV.

How did you meet Abel Ferrara?

I finished NYU in 1977. Abel called NYU graduate school and asked who was the best DP. They recommended me. I went over there, we smoked some cheap Mexican weed – that was my job interview. And then I started on The Driller Killer. It was myself, my future wife as my assistant and the first woman first assistant in the union in IA, my two Dobermans to guard the equipment, my van, and some of the smaller lighting equipment I had. I got $100 per day for that. We shot in Max’s Kansas City (the legendary NY punk club). In the last days of the shoot, I shot for 50 hours straight. I don’t remember much of it. We turned on the light in Max’s Kansas City, and every cockroach, every rodent came scurrying out of its hiding place. “Several pints of blood will spill when teenage girls confront his drill,” was the tagline. And it opened in the midwest in a bunch of drive-in theatres. We got our first review, and it said, “Abel Ferrara makes Toby Hooper look like Fellini, and the lighting was so dark, it gave me a headache.” We were thrilled. We actually got a review in Variety. Who cares what it said. It gave us some legitimacy.

“In high school, the novel ‘Farewell to Arms’ was one of the driving forces for me to go into the military. Hemingway was heroic and liked big things. He had a big life. I never wanted to have a small life. It’s better to have this life rather than this life of quiet desperation. Working with Abel doesn’t gives you this. It’s always incredibly chaotic on the set. He thrives on this.”

Ken Kelsch ASC

Abel Ferrara asked you to shoot Bad Lieutenant. How did this come about?

After The Driller Killer, I was teaching at the CETA and was gaffing commercials and stuff. Abel and I argued, and I refused to shoot Ms 45. I didn’t hear from him in eight and a half years. In the early hours of one morning, I got a call from him. He said, “Yo Kenny. What are you doing?” I said, “What do you think I am doing? It’s four in the morning.” He said, “It’s 1am in LA.” We had a one-hour conversation.

Abel flew back to NY. We met at the loft on 18th St. Abel and I decided to do a pilot for FBI Untold Stories, which Abel got fired from. We never finished it. It was with Woody Harrelson’s old man, who claimed to be the second gun in Dallas on Kennedy’s assassination, among other things. I worked with him for a couple of weeks. Abel said he wanted to do Bad Lieutenant. I met with Harvey and Abel, and we made preparations to do make the film, which I did for next to nothing. I was fairly successful at shooting commercials. We shot Bad Lieutenant in twenty days. Harvey (Keitel) was phenomenal. It was basically one take. It was the only film I’ve ever done, where we made a predetermined premise. The premise was that this would be like a documentary, and it would be a nonjudgemental documentary. We would keep Havery in MCU, and he would just do what he did. We decided It was the only time when we had a plan in prep that lasted through the entire film. And the plan was this – the camera would be the dispassionate observer. It would keep in medium close-up and would follow him around. I would document his existence as the scum of the earth. There is no reclamation for what he is. This guy is so bad. He does strive for redemption and is redeemed in the end. Abel’s films are always about the same thing. He was saying, “we’re making Driller Killer, which is about redemption.”

We had no money. We could’ve had a bigger budget if the film was R-rated. But everybody, including Harvey, was well behind the idea that we’re going to do it NC-17. The only NC-17 art film prior to that was Henry & June (1990). We had our prep, and we couldn’t afford pretty much anything.

What was your crew like?

I basically gave away my truck. They made a deal with teamsters. Some of the teamsters were terrible, probably because they were working under rate. They were hammered on the job most of the time, driving my stuff around. I had to load the truck myself. I hired Dennis A. Livesey as an assistant. Dennis is the exact opposite of me. I am sort of a “paint in broad strokes” guy. Dennis is the opposite of me – exceptionally organised, deliberate, and steady. The nicest guy in the world. Dennis helped me for 20 days. We were shooting wide open. He never gave us an indication of what the actual take would be like. He would do subsequent takes. But the simple fact was that he “would put his guts into the Cuisinart” for this one 10-12 minute take until he could hear the roll of film flapping around in the magazine. For me, it was great to operate on it because Harvey’s acting was so superlative and so dreading and so dark and so unrelenting that it was amazing to have the best seat in the house as I was following him around.

You used 35mm 4-perf 97 stock? Why did you choose this particular stock?

I shot underexposed. It had a very distinct and big grain structure, which I liked for the film. I rented retched BL3. They gave it to us for next to nothing. It was old, noisy, and heavy. The film was almost entirely handheld. I put a couple of trucks together in terms of equipment. I rented equipment two or three times; then I would buy it if I could afford it. I had accounts in various places like Mole-Richardson, Panavision, Barbizon Lighting Company, CSC. We shot 100,000ft of the film in 20 days. The BL weighed lbs. We shot full 1000’ mags. If I tried to use an 850’ “short end” Harvey would complain, “that wasn’t a 1000.” Abel would say: “We’ll blow a dime on this take.” One camera shoot. 1,000ft film single take (10 min/per shot). I don’t think that there were any old 35 BLs outfitted for 3-perf. That came later with 17×9 TV. Technoscope existed (2-perf), but I think that was primarily European, i.e., Sergio Leoni. I was never a fan of Fuji but they came a long way towards the end. Just as good as Kodak, but all my contacts were with Kodak. I really liked the graininess of 5297. I thought it helped with the documentary style.

You managed to get some unique locations in New York. Can you elaborate?

We didn’t have many locations. Last week of shooting, we filmed at Mickey Rourke’s loft in the Mayflower Hotel. During the last week at Mickey Rourke’s loft, I asked grips and electricians to construct Baylights, so we had them overhead and could shoot anywhere in the

apartment. There were no light stands. I could follow Harvey around the apartment. There was a great soft light in there. Luckily there was enough space to shoot. As I said, it was a documentary about what’s was going on. The Times Square driving scene was dangerous. I was driving around with Harvey ranting and raving with a 60lb camera on my shoulder. The shooting of the radio was an insert. The car pullover masturbation scene was across from Debbie Harry’s loft.

Can you talk about the collaboration between yourself, Abel Ferrara, Harvey Keitel, and Zoe Lund (actress/Bad Lietenant co-writer)?

When I met with Harvey, I felt like it was almost a job interview until I mentioned that we had worked together on Murder’s Rock and I talked about some of my military services. Harvey is a proud former Marine, who wouldn’t be. Things got smoothed out.

But it is much more about Catholic Redemption than Driller Killer. I think that’s the driving force. How can someone so bad ever experience redemption?

Abel and I made 14 films together. Usually, the scripts are 20-50 pages long. He loves spontaneity. There is never enough time to do what I want to do. Abel is impatient, but I have the ability to be spontaneous. So you have to make decisions fast. It’s all about plan B. Things will happen on a set. During my favorite scene, when Harvey is walking through the club, Abel said, “don’t light him for every place; we know what he looks like”. So I turned the lights off, and he walked through the crowd and all of a sudden, it’s totally black (for two seconds), and suddenly he was lit again. It was a much better idea than my original idea. I make it a serious practice not to trap the actors by light. Harvey did a lot of casting with us and got us a lot of talent from The Actors Studio.

Harvey was a dedicated actor and it was an intimate film pushing all the boundaries. When Zoe Lund shot him up with a saline solution, he was a bit nervous. However, as a DP, I always tried to maintain a safe environment. I think he committed himself totally to this whole movie. I actually didn’t think that anyone was capable of going where he went. He did it. The script that Zoe came up with was much more metaphysical, circuitous, and convoluted.

The Addiction, your next film, was a metaphor for a life of addiction. Was Zoe Lund the inspiration for the film?

Some of the stuff Zoe wrote was visionary. She graduated from college when she was 16 and spoke five languages. Unfortunately, she fell victim to heroin addiction. The Addiction was a metaphor for a life of addiction. It is my favorite film. The problem with The Addiction was we had no money. Abel came up with this idea. We would own the film. So I got the crew together. I did it the way I wanted to do it. I shot it black-and-white. I hard matted it in the camera in 1.85 to avoid 4:3 TV ratio in the transfer to tape. But they center extracted it. The last transfer I did on Blue Ray was much closer to my original vision. I thought it couldn’t be changed. I wanted to shoot Kodak Plus X [a black-and-white panchromatic] film but didn’t have the crew. I think we were three electricians and three grips. And we had no condors or anything, so for a lot of the night stuff like that shot in a street in Manhattan, I had my guys to haul up my Maxi Brute on the building. This was brutal for those guys. It was a trying time. But to shoot black-and-white as a DP is great. You get nine shades of grey [zone system]. You’re in a totally different environment. It is all abstract. As a DP, I consider myself a source-driven minimalist unless I am going to make a stylistic leap, where it’s going to be all stylised. I am capable of doing either way. I make the decision, and I figure out from then on exactly how I will address the frame, the set, and what we’re working on during the day. I’ve been a still photographer since I was twelve. I had my own darkroom. My old man taught me a lot of stuff. I had an old camera, 120 films and I love black-and-white. I made my own emulsions, platinum print, Sodium Bicarbonate, colour printing.

Tell me about your visual plan.

I was happy as a DP to shoot black-and-white because it’s a very stylised art, where your separation only comes from using nine shades of grey. As a DP, it was very challenging. I did it once, and I would never do it again. With the exception of cinephiles, people don’t go to black-and-white movies. Maybe the The Artist and Schindler’s List. I used my truck, no condors. My poor grips had to haul Maxi Brutes Nine Light 9000 watts, PAR bulbs to the corners of buildings. It was very difficult. Twenty days again [18 days two days for reshoots]. We shot on Panavision.

Thematically again, it was all about resurrection, redemption. It’s the same thing over and over again because it’s obviously Abel’s concern. He is trying to figure out how to get out of the trapping of earthbound existence and somehow transcend the dirtbag that you are and go out to the next step on your spiritual plane. The film starts with the footage of the Vietnam War. I went to Vietnam because I was in the Special Forces. When I was early on in the 6th Group (USSFs), guys already had four or five six-month tours behind them. It was the only war we had. This film is the most stylised of Abel’s films, not only in terms of my photography but also in terms of costuming, events, scripts, the acting, for Christopher Walken theatrically the most dressed out as Peina. He was phenomenal. He took it and ran with it. The amazing amount of disdain he was able to portray in that sit-down. Annabella Sciorra looked very stylised, like in old vampire movies, because this is all about resisting temptation. Michael Imperioli, who plays the missionary, and Lili Taylor, who plays the vampire, were a couple at the time. It was a great dynamic. Missionary refuses her, and she goes to the closet and rips her clothes off. Lili brought to the film this wonderful spontaneity. It was basically one take. I doubt that we even did doubles for close-ups. There is a lot of humour in the movie as well. Lili Tailor takes a lot of notes, develops her character; she knows her character’s backstory. There is nothing she can’t say about her character. It makes her the best actor around.

I loved the costuming of this movie [costume design by Melinda Eshelman]. I loved the production design by Charles Lagola. We had a screening at MOMA in May. It was a fantastic print. For me, it was a great pleasure to sit up close with my kids and to see this movie I enjoyed so much projected on a big screen. This is what being DP is all about; it’s not just a paycheck.

You shot in painter and filmmaker Julian Schnabel’s loft?

Yes. Julian was very kind to lend us his place for a day. There’s a Picasso in his bathroom.

Addiction is such a unique film. What were your aesthetics and influences?

The idea was that we would own the film, and our desire was to make this film black-and-white because I knew that I wouldn’t have this opportunity again. I grew up watching black and white TV. I saw Dracula in the theatre. After that, I couldn’t sleep for weeks. My father asked me why I wasn’t sleeping. My father said that when he was a kid, he saw a stage play of Dracula with Bela Lugosi and couldn’t sleep for years; it was so scary. I shot in Tri-X. The lab loved it. I looked through timing lights. My exposures were right on.

Can you talk about the philosophy of the film? Does categorical imperative exist in a vampire or not?

Predators are seductive. Seduction is pure intellect. The vampires in the movie are NYC pseudo-intellectuals. Does a vampire know the better of two ways to go no matter where she is seeking her prey? Eventually, she does. Ultimately, you go from being a total predator to Peina. You are going beyond your hunger, beyond your addiction. You have to transcend your addiction, and that what she does; that’s why she is alive reborn at the end of the movie. She walks past her own grave in broad daylight. We keep making the same movie over and over again. It’s all about redemption.

How did you express it visually?

Visually I lit the stuff that I thought was emotionally weighed most heavily upon the film. That’s the way I always lit. I lit Peina when he is in his chair. I lit him a certain way when he comes out of the shower. There are different styles I use throughout, lighting black and white. In certain scenes, I am much softer. In the scenes where she is a predator [when she takes a syringe of blood out of the homeless man’s arm], I got a 10K with a bare bulb that gives her a big shadow circa the 1940s on a back wall. The monster mash scene was lit just enough not to get the actual details. There was a lot of religious art cramped into a single captured frame. I always figure out a way to separate the foreground, the middle ground, and the background. Even though it is a black-and-white movie, I am always working on giving you a three-dimensional presentation in two-dimensional projection. These are the basic rudiments of my black-and-white photography, which I did for decades.

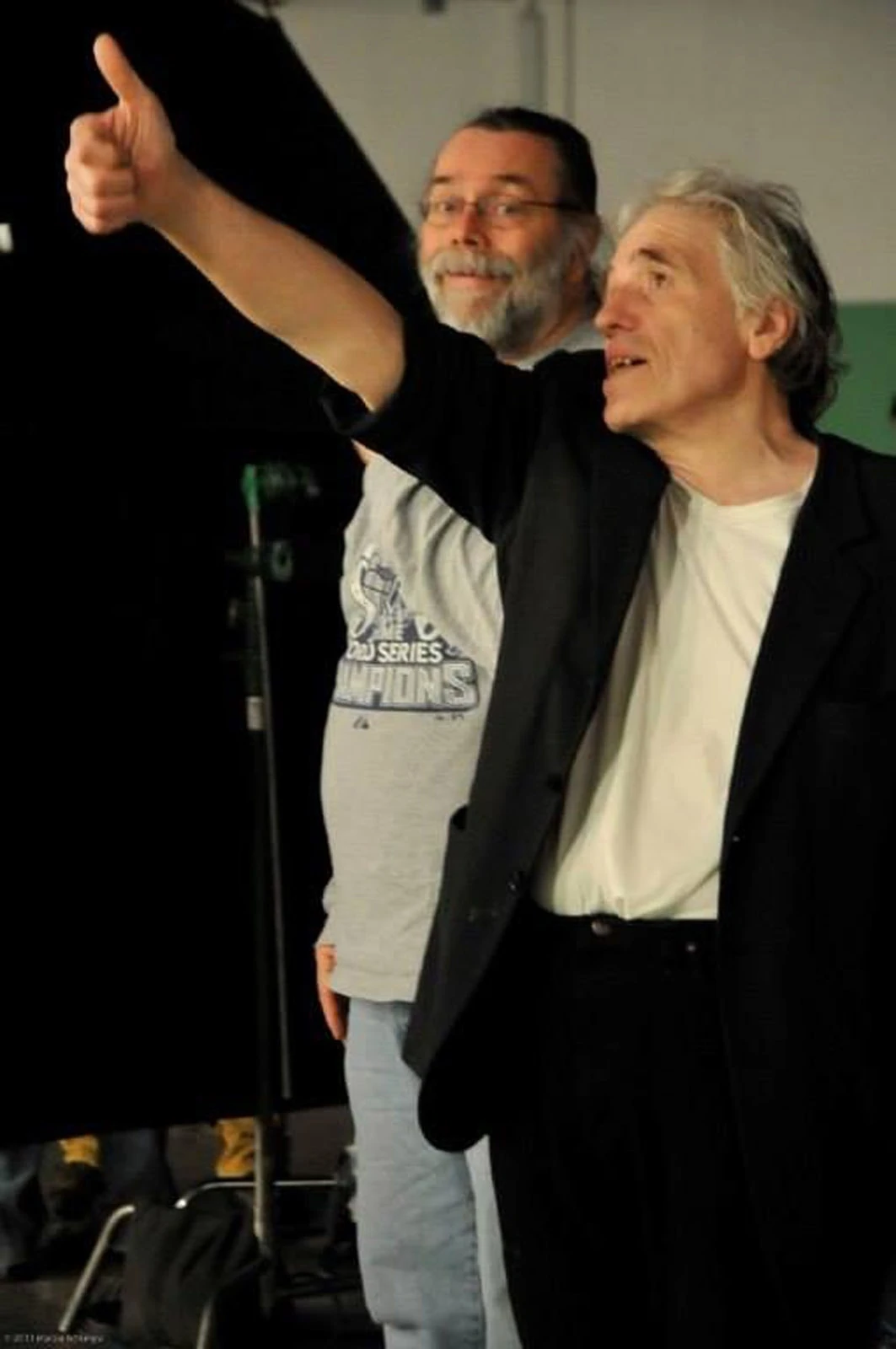

One of your latest movies with Abel Ferrara is the controversial Welcome to New York. Can you tell me about it?

It was an actor-initiated project. Gérard Depardieu is very similar to Keitel. He delivered on that first take. He was devoted to bringing the truth to the character. Jacqueline Bisset brought her best fiery game. A lot of scenes were improvised. We were influenced by

New Wave cinema. Depardieu despised Dominique Strauss-Kahn for seducing young people. Depardieu thought it was a story about terrible government corruption.

I tried to film the rape scene objectively. The rape was never proven. They settled out of court. She got a million dollars. That woman’s character had some dubious echoes. It was never proven. Was she raped or not? Was it an elaborate scam or not? That’s what I mean by objective.

Where did you shoot the film?

We filmed in Strauss-Kahn house in Soho. We shot on Arri Alexa . We then shot in prison. It was all handheld without much lighting going on. Everything was improvised. I carried the camera good quarter mile doing this and that.

BY: Karen Pyudik