Shooting on tungsten stock, cinematographer Jack Hamilton and the team behind Killing Boris Johnson sought a textural image, grounded in realism. Hamilton takes us behind the scenes on his National Film and Television School (NFTS) graduate film, filmed over almost 10 locations across seven shooting days.

In Killing Boris Johnson, Kaz’s mum has committed suicide. He decides that Boris Johnson is responsible for it and decides to come up with a plan to kill him.

British Cinematographer: What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

Jack Hamilton: Although the title might sound hyperbolic, the core elements of the story are extremely personal to Musa Alderson-Clarke, the director, which required a huge amount of trust from both of us when developing the visual language. The first thing he said about the look is that he wanted it to have a heightened sense of reality but to be grounded in realism – a sentiment we carried with us through the process of making the film.

A lot of our references were handheld with an ‘ob-doc’ feel which we felt added that sense of realism and allowed the freedom to react to performance. It also complemented the anger and intensity of the character. We were selective about when to be handheld and how intense that handheld was as to not desensitise our audience and be more impactful when we did push it.

Tonally we opted for a cooler/bluer palette, both in the camera capture but also the art direction with help from our production designer Yung. This helped create a world around Kaz that felt oppressive and bleak. To contrast this, Kaz was dressed in a red hoodie to emphasise him not fitting in with his surroundings. We wanted to make sure that even though we had a cooler palette, that there would be some vibrancy to the image, honouring that ‘heightened sense of reality’ we’d initially discussed. This vibrancy and saturation was achieved through how we treated the stock and graded.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

JH: Thematically and visually we looked at films like Taxi Driver, the Pusher films, Good Time and Sound of Metal. These were tense films with high stakes and a lot of grit and mood – films that had a textural and realistic feel to them but also a sense of style and a heightened image.

I also looked at a lot of ‘shot from the hip’ street photographers like Robert Frank and Saul Leiter.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

JH: We shot nearly 10 locations over seven shooting days, often shooting out two locations in a day. Unit moves are extremely challenging and time consuming and it’s a credit to our 1st AD Ciara Gallagher and our producer Solomon Goulding and the production team for figuring out the logistics of such an ambitious shooting schedule with minimal creative compromise.

One challenging location was an operational commuter train. Our budget unfortunately didn’t allow us to have a sectioned-off carriage to shoot in. So, when our crew got on the train to shoot and realised all the seats were taken, we had to think on our feet. We placed our lead on a box next to the train toilets and faked the train door as a window by shooting tighter than we planned. Honestly, I think it ended up really working.

BC: Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses? What made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

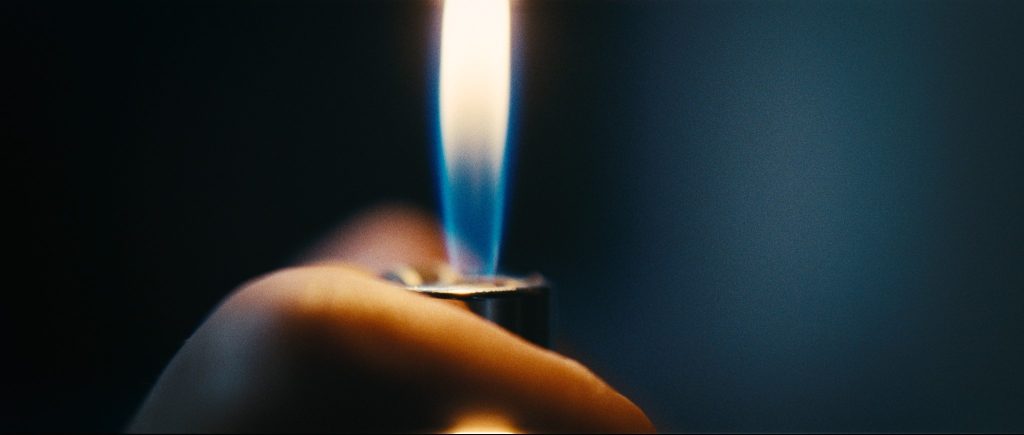

JH: We shot on the Arricam LT which is a 35mm camera. We knew almost immediately that we wanted to shoot Killing Boris Johnson on film. Kaz’s character worked at an ad agency where he was growing tired of creating glossy ads, so we wanted to make sure that his perspective felt as far from that as possible. We wanted a more textural image and again something that felt more grounded in realism.

Not to throw around buzzwords, but there’s an authentic, honest feel to filmic images that we really wanted to embrace. Again though, we wanted that ‘heightened sense of reality’ so brought in some vibrancy and saturation to the look by push processing the stock on the interiors. This also added more texture and grain. For the exteriors we didn’t push the stock as we were shooting July for November and didn’t want to enhance the hard sunlight too much to avoid having to fight it in the grade.

We shot entirely on tungsten stock (A combination of 200 and 500T). This meant the capture was already truer to the bluer/cooler palette we were striving for before we’d even gotten to the grade.

I tend to opt for a cleaner, sharper lens when I shoot film, so I used a set of master primes kindly supplied by Panavision. We wanted to feel close to Kaz and his perspective so were often on the wider end of focal lengths so the camera could be physically closer to him. This also allowed us to pull him out from his environment as opposed to a longer lens which would’ve blended him into the background.

A big shout-out to Ash Leontyne, my focus puller, for managing the camera team and kit and keeping me sane the entire shoot.

BC: What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

JH: Our approach to lighting was with the principal of ‘enhanced naturalism’. We wanted the filmic lighting to be an extension of the actual sources you could see in the frame and often the source you could see in the frame was the filmic lighting.

We wanted to embrace the starkness of fluorescent bulbs in the office environment and the warehouse Kaz lived in. We sometimes used the actual fluorescent bulbs or sometimes swapped them out for Astera tubes if I wanted more colour or exposure control. Yung had sourced some fluorescent housing fixtures that fit the Astera tubes inside them that he, my gaffer Adam and I placed tactically throughout Kaz’s living space and could dial in the exposure/colour easily from shot to shot from Adam’s wireless gaffer control system.

We also did a lot of negative fill work. It’s a moody, high stakes film and that’s reflected in the contrast of the lighting. We also had a combination of Lightmats and other LED fixtures rigged in to the ceiling for ambient/fill that were again linked to and easily controllable from Adam’s gaffer control.

My lighting package was kindly supplied by Panalux.

BC: What were you trying to achieve in the grade?

JH: The celluloid and processing had done a lot of the leg work for us in terms of colour before we’d gotten to the grade. My colourist Aiden Tobin and I had worked together on nearly every project I’d shot at the NFTS and it’s been great to watch him grow. Having worked together so much meant that we had a shorthand, and he knows my taste well. So, it was easy and quick to communicate ideas and get the image to where we wanted it.

Mostly we graded in a touch more contrast and saturation and tweaked a couple of my on-set exposure mistakes (Sssh.) Aiden also did a bit of shaping/moulding work to again enhance the contrasty look but managed to do so without losing the 35mm quality.

BC: What were the most challenging parts of the film to shoot and how did you overcome those obstacles?

JH: The schedule and pace we had to work at was probably the most challenging part of the shoot. Musa and I knew from the start that this was probably going to be the case so during pre-production we made sure that we were as prepped as we possibly could be. He even convinced me (begrudgingly) to have our shot list storyboarded!

By being so prepared though, and having all of this on paper it meant that when we were in sticky situations we knew what we wanted to achieve from each scene so could easily throw that plan out the window and get to the visual and emotional end goal we’d originally intended – even if it was with fewer shots.

BC: What was your proudest moment from the production process? Is there a specific scene or shot that you’re especially proud of?

JH: Individually it’s hard to pinpoint any specific moment I’m proud of. I’m proud of the entire film and every single person that worked on it. I’d say personally, I’m most proud of my collaboration with Musa. To be trusted to shoot such a personal story was genuinely one of the most rewarding things I’ve done. Musa has an extremely clear vision as a director which is a quality I love. He’s collaborative and open to ideas but knows when to say no and push back. It was a tough, intense shoot but every single crew member was dedicated to putting as much effort as they could into this film and that’s because it was obvious how passionate Musa was and how fun a place he made the set to be.

The specific scenes and shots I’m most proud of aren’t necessarily the ones that were logistically or technically hard to achieve, or the ones with the flashiest cinematography, but the ones that conveyed the emotion of Kaz best. This often was taking a back seat with the photography and giving space to the performance.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production that you’ll take with you onto future productions?

JH: I learnt a lot about filmmaking and myself making this film. I think I’m a better collaborator, communicator head of department and organiser all through the triumphs and mistakes I made making Killing Boris Johnson.

I think one thing I’ve really learnt to appreciate is the importance of performance. Story and connection are why we love film so much and of course everyone involved in making a film contributes to that. But ultimately without a strong, believable performance to connect to, the other parts are almost pointless. Shadrack our lead smashed It. I’m completely in awe of his talent and what him and Musa managed to achieve together. A lot of the time my job was to be ‘selfless’ and not be too ‘loud’ with the cinematography and let the performance speak for itself. Which is a lesson I’ll take forward.

BC: What would be your dream project as a cinematographer?

JH: I’d like to think I’m a versatile cinematographer when it comes to narrative subject matter. If I can connect to the story in some way, I’ll be inspired to build a visual language. My favourite part of the job and kind of the core of what cinematography is – to translate emotion, story and feeling into a visual language for an audience to interpret. Any chance I get to flex that muscle, I’m happy.

I would say that queer stories are ones I’ve always felt most connected to and had a drive to shoot. A queer story in Cornwall (where I grew up) would be a dream.