Midway through a week of film festivities and frolics at Poland’s EnergaCAMERIMAGE Film Festival, a missile struck Polish territory. The explosion happened in the village of Przewodów, near the Ukraine border and almost 300 miles from the festival’s home in Toruń, but shockwaves were felt there too. It was a stark reminder of the sombre backdrop to this year’s festival.

To show their support to their eastern neighbours, Camerimage’s organisers welcomed two Ukrainian film festivals into the fold: OKO International Ethnographic Film Festival and KINOKO, Ukraine’s first film festival dedicated to cinematography.

KINOKO was given space to present one feature and one documentary film that had triumphed at previous KINOKOs at Camerimage: Nariman Aliev’s Homeward (Додому) and Simon Mozgovyi’s Salt from Bonneville (Сіль з Бонневілю). KINOKO also ran a special ‘Cinematographers at War’ seminar, where Ukrainian DPs shared their own experiences of filming during the conflict.

OKO, meanwhile, screened eight feature and 16 short ethnographic documentaries from around the world as part of the festival. Outside of the main competition, OKO also spotlighted Ukrainian films in a series of special screenings. At the opening gala, OKO’s founder Tetiana Stanieva and programme director Elena Rubashevska introduced a reel of Ukrainian filmmakers who have downed cameras for weapons in the fight for their homeland.

Speaking after the festival, Elena shared more about OKO’s history and mission in a special Q&A with British Cinematographer, below. Please also consider supporting Filmmakers for Ukraine. Here you can offer a financial donation, find or give help, support Ukrainian filmmakers by streaming movies, and much more.

How did the idea for the festival come about?

OKO was born three years ago – we’re a very young film festival. We were born in the height of COVID as well, so the first edition was online, and the second edition was combined. Now, the third one has happened outside of [Ukraine]. That’s why we’re saying that we’re not afraid of anything – even if the apocalypse happens, we will still go on somewhere on another planet. Nothing can stop us!

But jokes aside, it all started when Tetiana, who’s the director of the festival, and I met. I’m originally from Donbass and Tetiana is from a region called Bessarabia, which is in the south of Ukraine. We found out that Tanya was full of misconceptions about Donbass, and I actually thought that Bessarabia was part of Romania or Moldova but not Ukraine. We were absolutely appalled by the fact that we live in the same country but know nothing about each other. So, we started talking and we started sharing. We’re both big patriots of our respective regions and this mutual love transformed into something bigger.

We started thinking about how much we know the other regions of Ukraine, because we often know nothing about each other, and we never travel to each other’s hometown or region. We decided to start with Ukraine, but we thought, why not embrace the whole world? So, we started the International Film Festival.

Where does the festival normally take place?

It normally takes place in Bolhrad, a smaller city in Bessarabia. It’s a southern region, close to the sea and close to the border with Romania and Moldova. It’s also very challenging to organise the festival there because Ukraine’s cultural life is centred around Kyiv, the capital, and very few film festivals happen outside of there. There is Odessa Film Festival, of course, but they are very well known and have a lot of support. We were no-names, but we were very ambitious.

We said the idea would be to show people outside of the capital that cinema in Ukraine exists, and that cinema exists in general, because very often in the regions there are no cinemas at all. For example, there are some people my age – and I’m 30 – who have never been to the cinema. For those of us living in the big cities of Ukraine, we’re closer to Europe in all other respects, but the rest of Ukraine lives in a totally different world. So, we decided to expand this culture, and specifically cinema culture, to the regions.

We’re also combining two qualities – cinema, of course, but also ethnography. I graduated as a director and screenwriter and Tetiana, the director of the festival, graduated as an ethnographer. We combine our knowledge and with this, we create something more than just a film festival.

The aim of the festival is to combine these ethnography and film values. The second aim is to let Ukraine discover the world and let the world discover Ukraine, and to present Ukraine from a bit of a different perspective to the world. Nowadays, unfortunately, in many countries’ media, Ukraine equals war, and it’s a shame. Of course, it’s very important to talk about it and most people are only talking about it. But we are very afraid that we will forget that our country and culture is much more than war.

Ukraine and Ukrainian culture are actually super cheerful and very festive – we have a lot of traditions. Even in a modern Ukraine, there’s lots going on apart from the war, and we want to preserve this. We want to promote the alternative image of Ukraine that unfortunately is not presented to other film festivals very often.

How did the partnership between OKO and Camerimage come about?

When the war started, I was actually in Donbass, location scouting for my documentary. I had to flee and had no chance to get back to my home in Bucha. I had no documents, and all the roads were destroyed by that time, so there was literally no way to get back home, so that’s why I ended up in Poland.

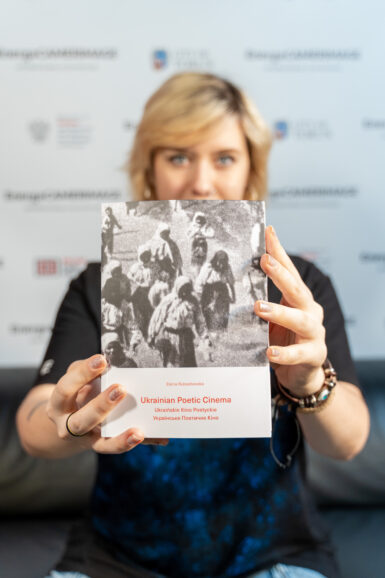

On the third day of my stay, I was employed by Camerimage, and we started several mutual projects together, so I worked for them as a programmer. We also published a very cool book about Ukrainian poetic cinema, and we screened a retrospective here at this edition of Camerimage. But [Camerimage] also offered to support OKO – not only a couple of special screenings or one day of a festival, but to support the whole edition. It was extremely generous.

We couldn’t believe it because a lot of Ukrainian festivals right now – even leading festivals like Odessa and Docudays – are doing collaborations with European film festivals, but we were so generously offered to be hosted as a full-scale festival. So Camerimage gave us a unique location: the Kino Camerimage, a former church-turned-cinema. They provided us with all the technical infrastructure to make screenings happen. They hosted all our directors and paid for tickets. So, they did more than just ‘help’, they gave us wings!

It was our first full-scale edition, so it was extremely beneficial to have all the directors come in from all over the world. And since we are an ethnographic and documentary film festival, a lot of films touch on very complicated and sensitive subjects. It was very interesting to forget for a moment that although we have a lot of problems back home, the whole world is actually suffering, because we had films from Latin America and from Africa. Being in touch with other people who suffer, who look for a way to solve this eternal suffering and who’ve succeeded in it, is very beneficial for us at the moment.

We’re building this infrastructure. It’s not only about this one week, or 10 days of screenings and meetings, it’s about the future collaboration, it’s about the fact that we know we have each other from now on and that we have friends all over the world. Also, we have a cash prize for the festival’s short and feature film winners. Every year, the winners say that they won’t take the money for themselves, but we will send them to the people in our movie. This year, for example, our winning film I Am Chance, realised by a Belgian director but shot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo [DRC] in Africa. The filmmaker will redirect that cash prize to the children of Kinshasa, the DRC’s capital. What this money might mean for those children, we cannot even imagine. That’s when we realised that we have to keep going with this festival – we’re changing something in this world, and that’s the most precious feeling.

Tell us more about your OKO Travels initiative…

We have partnerships with many film festivals and clubs, and even music and ethnography festivals in Europe. Despite the fact that many of them are also suffering from budget cuts, they still want to support Ukraine and they often suggest that we have some special screenings, a panel discussion, or present Ukraine in a way we find suitable at the moment. We’ve already had screenings in Italy, in Bulgaria and in Finland, and right now we’re travelling to Bulgaria. Bulgaria is a special country for us because Bessarabia is a region traditionally related to Bulgaria, where ethnical Bulgarians live, so that’s why it’s important to us to keep this collaboration going. And after that, OKO Travels goes to Bolhrad, its native town. Unfortunately, I won’t be there, but rest of the team will go back to Ukraine. I’m the only team member who actually became a refugee – all the others stayed in Ukraine.

For me it’s not possible to go home at the moment because I cannot lose my refugee status. In fact, my home was destroyed – I have nowhere to go and I’m very scared to go back. That’s why even going back for the festival, unfortunately it’s not possible on a mental level, I would say. And for the whole team, of course, it’s very symbolic but also very challenging. We cannot plan anything.

What about the festival’s future?

The situation in Ukraine isn’t getting better. As Tetiana said in her speech at the Camerimage opening gala, it’s not an apocalyptic movie, it’s not special effects that you see in the news… People live this reality, and they actually survive. Under such circumstances, culture or film festivals aren’t a priority. OKO really unites us and helps in the darkest times, but if there is a choice between survival and making a film festival, of course people prefer to survive first and foremost. So, after all the huge celebration and big success we had in Poland, it’s very weird to be back to the reality that we have in Ukraine. I don’t think it’s possible to organise a festival in exile year by year. We must all hope for the better, but I must say where we’re trying to be optimistic, we’re also realistic. So, until New Year, I think we will just have a rest, have the rest of our screenings in Ukraine, then we will have a meeting and see where life takes us.

How can filmmakers and film fans in the UK support the wider filmmaking community in Ukraine?

I would say it’s very important to remember for international communities that war has not always been the reality in Ukraine, and it never defined Ukraine. Right now, we’re going through this very hard period.

I’ll give you another example – I have a lot of friends, filmmakers from the Balkans, and 30 years later after the wars, they are still suffering from this cliché that the Balkans equal war. Both governments and international film funds first and foremost support projects related to war, but the Balkans are exhausted of that. They want to develop their culture, but unfortunately money only goes to war. We are very afraid that the same will happen to Ukraine.

Obviously, there will be a lot of stories worth highlighting related to the war. But if I had the chance, I would ask the international filmmaking community not to forget that Ukraine is much more than war – we are a very rich, hospitable country. We have very diverse nature, we have the sea, we have mountains, we have technology, science and culture, and we would love to celebrate that and to speak more about that. That would be my ultimate message.

OKO International Ethnographic Film Festival’s winners

Short film winner – Nomad Girl (dir. Rouhollah Akbari, Iran)

Special mention – Wormwood Star (dir. Adeline Borets, Ukraine)

Special mention – Brave (dir. Wilmarc Val, France)

Feature film winner – I am Chance (dir. Marc-Henri Weinberg, Belgium)