BOLD VISION

When Greig Fraser ASC ACS and his creative collaborators returned to the desert to continue bringing Denis Villeneuve’s vision of sandworms, spice, and spectacle to the screen they evolved the world of wonder by entering new visual territory.

Living up to the immersive cinematic experience of 2021’s Dune and the accolades it garnered was a gargantuan task for its filmmakers when tackling Dune: Part Two. But they rejoiced in the opportunity to continue the voyage of creative adventure, expand the Dune universe and captivate audiences with the next chapter in the epic story.

“We’d just come off a successful awards season [Dune won six Oscars and five BAFTAs, including for cinematography] and started prepping Part Two in Budapest four days after the Oscars,” says cinematographer Greig Fraser ASC ACS. “It was time to get serious again and everyone was thinking about how to make the second film even better. That was a constant pressure on us all. It was an important exercise in forgetting the past in some respects and also forging a new path.”

Having shot Dune – based on part of the first novel in Frank Herbert’s futuristic sci-fi series – stood Fraser and director Denis Villeneuve in good stead. Obstacles had been overcome and creative relationships had been formed and an entire movie’s worth of prep allowed them to delve even deeper into the source material, taking bigger and bolder risks.

While Part One (covered in the November 2021 issue of British Cinematographer) drew to a close with protagonist Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) escaping into the desert with his mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), the second instalment of cinematic sci-fi transports the audience back to the Dune universe as Paul unites with Chani (Zendaya) and the Fremen people of the desert planet Arrakis to seek revenge against House Harkonnen, the conspirators who destroyed Paul’s family.

Tackling the second film’s new technical challenges and increased number of action-based sequences alongside Villeneuve and Fraser were trusty and talented collaborators who played key roles in the first instalment including production designer Patrice Vermette, gaffer Jamie Mills, 1st AC Jake Marcuson, key grip Guy Micheletti, visual effects supervisor Paul Lambert, and costume designer Jacqueline West as well as new experts in their field added into the mix.

Increasing the frame of fantasy

Early exploration into how to expand the world, saw Fraser and Villeneuve discuss what was most successful and should be carried over and how to enter new visual realms. While the second part of the first film was captured in IMAX, they felt Part Two – which predominantly takes place in the desert – must be 1.43:1 IMAX ratio in its entirety.

“In Part One, we shot Paul’s internal journey in 2.40:1 with anamorphic lenses and switched to spherical lenses and IMAX framing for his external journey. Part Two is all large format, adopting spherical lensing, to explore that big screen event experience we enjoyed in Part One,” says Fraser. “It was important we didn’t do the same thing, not just from an audience perspective, but to push ourselves further as filmmakers and explore new ground.”

Fraser’s ability to multitask, managing several units simultaneously, was valuable to Villeneuve, who considers him a strong ally. To fulfil the director’s ambitions of creating “the biggest canvas, the full immersive experience,” he relied on Fraser’s skill in shooting IMAX, the large format lending itself to the expansive nature of the locations and sets to create a sense of scale. For Villeneuve, Fraser is “a master with the format” and together they “made so much effort to bring all the tiny details of the desert and what it is to be walking on Arrakis.”

Capturing new and existing characters in Part Two was a fun creative exercise for the filmmakers which saw them move a step longer in their lensing choices. “Hopefully it’s not something the audience consciously notice because we weren’t that much longer,” adds Fraser. “Often with wider lenses, when you move in closer and fill the frame with a face, part of the joy is you really feel the intimacy. But we didn’t necessarily want the camera to feel close to the characters, so we deliberately went a little longer than the first, stepping up on almost everything we shot to really fill the frame with their faces. It became instinctual – when we put a lens on we used on Part One, Denis and I instantly felt it wasn’t right.”

During the three months of prep beginning in April 2022 – before the five-month shoot commenced – the team decided to increase the use of camera movement, cranes and Steadicam in the desert this time around, to keep Paul’s journey moving forward as his character matures, growing in confidence and power. They also explored the creative possibilities of capturing the exterior of Giedi Prime – the brutal home of House Harkonnen – which had not been depicted in the first film. To differentiate Giedi Prime from the Fremen’s desert planet of Arrakis, Villeneuve suggested a novel concept, sparking investigation into infrared techniques.

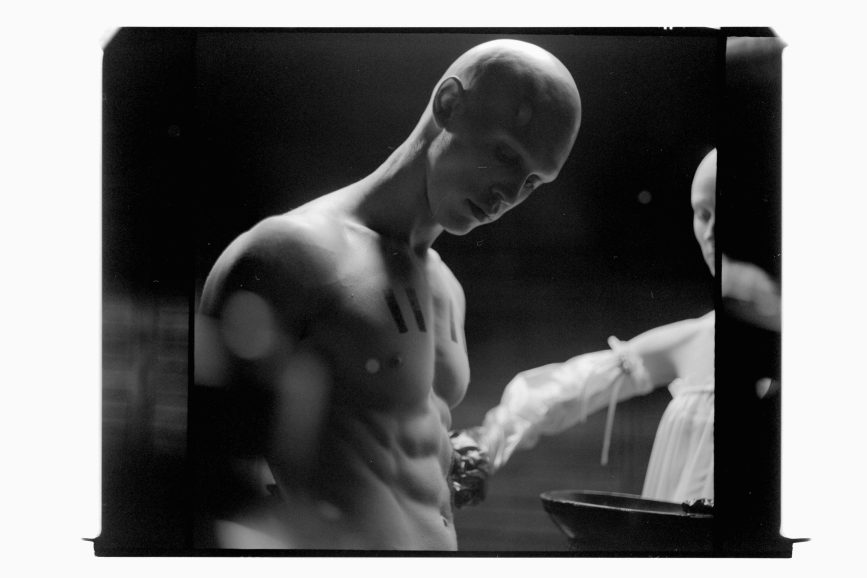

“Denis’ idea was that the sun on Giedi Prime doesn’t emit colour which also justifies how the Harkonnen ended up pale and hairless,” says Fraser. Having experimented with infrared cameras for some of 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story’s VFX work and lit entire scenes in Zero Dark Thirty (2012) using infrared light, Part Two presented Fraser with an opportunity to use it on camera with the IMAX-certified ARRI Alexa 65.

As a limited number of native black-and-white Alexa 65 cameras capable of seeing the infrared spectrum were available from ARRI Rental – which also supplied the Alexa Mini LF, lenses, and grip equipment – the IR filters were removed from regular Alexas. Using an 87c filter to block all visible light from the sensor, Fraser created an eerie end result when the colour was desaturated to monochrome.

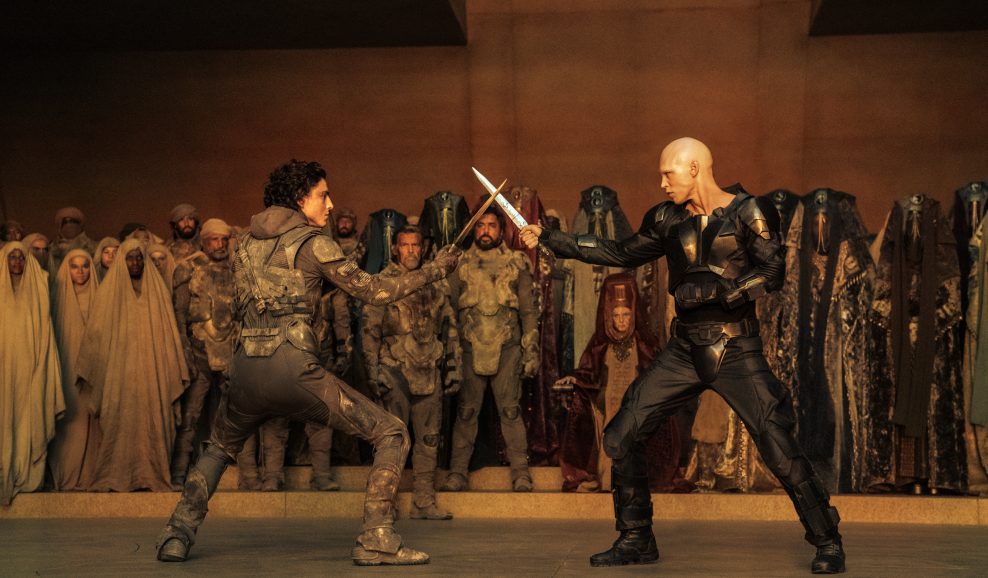

Considerations needed to be made when using infrared cameras to capture some of Jacqueline West’s costume creations. If the villainous Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler) was dressed in black for the pivotal arena fight scene, his clothing might not appear that colour when shot in infrared.

“Testing demonstrated that red goes black, denim goes white, and black displays with big chunks of white or grey,” says Fraser, who also shared results of the testing with Patrice Vermette to inform his Giedi Prime production design.

Having worked on Part One, 1st AC Jake Marcuson had an understanding of Villeneuve and Fraser’s approach when it came to focus and timings. Villeneuve often stood next to him and shared his monitor, liking to cue focus pulls during a scene. Marcuson highlights the infrared-captured fight in the arena between Feyd-Rautha and one of the Fremen as one of the more demanding sequences. “Judging focus was different as the sensor and lenses react differently when cutting the visible light. The focal plane on the sensor is different, even more so in the very bright daylight on a set that was built between two stages in Budapest,” he says. “It was 38 degrees outside and probably 10 degrees hotter on the set. Special reflective covers were made to keep the cameras cool as well as cooling gel packs and on occasions hoses were run into the cameras from air-conditioning units.”

Further new methods were adopted when the main and second unit captured the technically ambitious opening eclipse scene in which a dark orange hue washes over the sky and sand. “Grading the footage to look like an eclipse didn’t work, but then we discovered a Formatt Hitech Firecrest filter that cuts down the blue and green wavelengths,” says Fraser. “The theory is that as the sun is blocked, the colour evolves, a lot like what happens at dusk and sunset.”

By an exceptional coincidence, at one of the multiple locations in Jordan and Abu Dhabi in which the scene was captured, the crew experienced a real eclipse which was included in the final cut.

Fraser frequently worked with the Firecrest ND filters throughout the film, finding them to be reliable, consistent and hardwearing enough to withstand sandstorms. “You can’t get any harsher conditions than we experienced, so it was essential we didn’t need to replace filters every day. They allowed us to achieve the colour depth needed in exterior desert scenes.”

Conversations around colour turned to the use of green, which only appears at the beginning of Part One when the ocean world of Caladan is introduced and at the end of the movie. Green became more significant in Part Two as although there is little colour on Arrakis, the audience is introduced to the Emperor (Christopher Walken) and his more fertile home planet of Kaitain.

“There’s also a change in landscape and colour as Paul, Chani, and the Fremen travel from the north to the south,” adds Fraser. “The sand is more black and the terrain is more rocky in the south. It was important we mixed up the environment and didn’t shoot three hours of sand dunes.”

Part One’s process of shooting digitally and working with FotoKem to transfer to 35mm negative and scan back to digital on a Scanity film scanner – before the company oversaw all deliverables – was repeated. Refinements were made to LUTs developed for Part One with FotoKem’s supervising and senior colourist, David Cole, and new LUTs were created to cover new locations and events such as the Emperor’s Garden, the arena, and eclipse. “Again, we were involved in camera tests early, as well as doing a whole slew of tests to evaluate alternate processes that could be used in the ShiftAI film out process,” says Cole.

Much like Part 1, Fotokem created a colour bible of around 50 minutes of the film months ahead of the DI and spent time with Fraser and Villeneuve developing the looks as they would play in context of the whole movie. “This streamlined the grade when we started in earnest on it, as well as informed the creative team about where we thought we could be ending up in regard to the final look of the film,” adds Cole.

Other early testing included how the IR camera photography could be mixed with standard colour for the transitions and working out how the eclipse scene would work in regard to shoot and post production. The eclipse scene was shot with orange filters, but early on Cole discovered that to fully achieve the look Villeneuve had dreamt about for years, as well as the transition of the strength of the eclipse itself, he would need to go back to a neutral grade that stripped out much of the in-camera filtration. “We would wind it back in as the eclipse became stronger and then weaker, with the highest part of the eclipse fully embracing the filtered look as captured,” explains Cole. “By neutralising the filter, and then winding back in the colour, we could fully and believably hold out the blue of the Fremen eyes in the scene without them being ‘muddied’ by the filter.”

Transitioning between colour footage to IR footage from the stereo rigs was achieved through a partnership between the VFX and DI departments. “The IR footage all handled well and allowed us to achieve the brutality of the Harkonnen home planet,” says Cole. “Alignment and wipe mattes were created by VFX and then the final finessing, comp and grading of the two different elements was handled in DI.”

New territory

The team returned to Abu Dhabi, Jordan, and Budapest, shooting in different environments to Part One within each location and searching for spaces that would technically serve them as filmmakers as well as serve the story. The ambitious production marked the first time Villeneuve as a director revisited a universe and a story, with the aim being to avoid the audience feeling a sense of déjà vu. As well as finding new locations, all sets were new, requiring production designer Patrice Vermette to design new environments.

“What was beautiful from Part One is that everybody knew the boundaries, the colour palette, so we didn’t have to redefine those elements, just use the very specific language that had been tested,” says Villeneuve. “Patrice was more creative than ever and really blew my mind with what he brought to the movie.”

Cave of Birds – one of the director’s favourite sets – is meant to be carved in rocks where birds are nesting. Villeneuve views it as a “kind of Fremen shelter… very poetic and one of the most beautiful sets” he has seen.

“It’s basically a bone harmonica, which was my inspiration, and inside it’s just like fingerprints, which is another way to say identity, who these people are, giant fingerprints,” says Vermette, who designed the Cave of Birds set to allow the Fremen to tell their story and history.

The “visual bible” – a book of illustrations created by Vermette and his team of concept artists during the soft prep period – consists of all the settings to be showcased in Part 2. “This helps everybody visualise the “sandbox” in which they will all be playing for the coming months. The film would also now require 40 percent more sets to be built than the previous instalment,” says Vermette. “The illustrations contained in the “bible” all derived from 3D models that will serve other departments, from storyboards to previz, VFX, costume, and obviously Greig and the lighting department.”

Italy – a new location for Part Two - was found in the small town of Altivole. “Since the architecture of Carlo Scarpa had been a great influence on the aesthetics for both Caladan and Arrakeen in Part 1, Tomba Brion – designed by Scarpa – became ideal to set up the scenes on Kaitain. This would underline the influence of the imperium on the rest of the universe,” adds Vermette.

As well as returning to Origo Studios in Budapest to shoot some sequences, in order to reflect the expanding story additional sets were built at Budapest’s Hungexpo exhibition centre. “The movie’s scope and scale, and knowing all these sets needed to be built and shot in a short amount of time, meant we ran out of stages and had to rent the exhibition centre,” says Fraser.

Like the first film, the sets were large and complicated to light, requiring Hungarian gaffer Krisztián Paluch and his team put up their own grids in the exhibition centre. Although the 103,000 square foot, 45-feet high space gave Vermette and his team the opportunity to build sets to the scale needed for Giedi Prime, the Imperial tent and several other sets, some sets were too big to fit, “but we learned tricks from Part One to go beyond the physical space.”

Fraser, who collaborated with Vermette on 2018’s Vice and Part One, thinks “all of Patrice’s designs are amazing. I can’t even begin to tell you how much joy I got from looking at his designs for this movie. They’re so well lit, and he works so closely with his illustrators to really define how the spaces look in the artwork, raising the bar once again.”

Shooting extensively on sand in the desert presented technical challenges as carrying camera equipment, cranes, and tracking equipment to the top of 150ft dunes is no small feat. Finding dunes in Abu Dhabi allowing a long enough reach on the crane arm or which would make it possible to shoot at the desired time of day was a challenge.

“This time we were shooting in Abu Dhabi in November and December when the days were at their shortest, and the sun the lowest – conditions most cinematographers would kill to shoot in,” says Fraser. “While we shot some beautiful low sun sequences, Arrakis is a harsh planet so many big scenes such as the sandworm riding and harvester attack needed to take place in the middle of the day. We couldn’t shoot all the way through the day because the beginning and end shots would look too pretty, and wouldn’t match the rest of the scene.”

Therefore desert scenes were shot between 9.30am and 3.30pm and to maximise the shoot days and available sun, a micro unit with limited crew captured additional scenes which did not rely on harsh sunny conditions before and after this period.

Entering the Unreal

Working with Epic Games’ Unreal Engine allowed locations to be virtually scouted and shoots precisely planned according to where the sun’s path would be at specific times of the day, helping the crew including the 1st AD and producers. Fraser’s assistant, Tamás Papp, used the software to create renders of mainly outdoor locations in Abu Dhabi and Jordan as well as to determine placement of elements in the backlot and between the stages in Budapest. It was a powerful tool for multiple sequences including Cave of Birds, the sandworm riding, arena fight, and eclipse.

Prior to shooting, teams on the ground in Jordan, where the eclipse scene would be shot at multiple locations, captured photographs and 360 drone shots of the areas which Papp turned into 3D models in Unreal Engine. This allowed the team to see what the sun would look like later in the year when the shoot would take place.

“As we were shooting towards the end of the year, an area would only be in shade or sun for a narrow window of time, so Unreal Engine was a valuable planning tool to allow us to be as efficient as possible when shooting,” says Fraser. “Regular solar tracking apps or compass readings are great. But if you have to remotely provide precise timings for multiple set-ups in a short period, they can be blunt instruments for fine tuning the times of day you need to be at a location.”

As the complex arena fight required some shots in shade and others in sun it needed to be filmed between two stages of the backlot in Budapest, requiring grey walls to be built to create shade. Once again, using Unreal Engine to determine where sun and shade was at any given time of the day allowed the team to schedule the shoot effectively.

“Unreal also allowed us to work out in advance how far back we could get a lens for a long lens tracking shot for the sandworm riding sequence we captured in Budapest and featured a horizontal and vertical section of the worm on a gimbal rig that could be rotated,” says Fraser. “Unreal doesn’t replace a compass or common sense when it comes to photography but on a shoot of such complexity and precision, it allows you to make the right decisions so you can be more efficient on shoot day.”

As shade is scarce in the desert, in the Abu Dhabi “shadow lot” gaffer Jamie Mills needed to replicate the shadow created by a spice harvester for the attack scene which used cable cam to capture a long take. Unreal Engine previsualisations created by Papp determined four 150 tonne cranes, each with a 40’x40’ solid shadow material on, would be required, along with 24 industrial telehandlers with 20’x20’ solids on them. “For each sequence we moved these around ahead of the shoot, so the shadows worked out perfectly with the sun orientation to create the harvester,” says Mills.

Camera movement considerations

Shooting for IMAX felt right when telling Part Two’s bigger and bolder story, but capturing footage to be displayed on such an expansive screen demanded greater consideration regarding camera operation to avoid disrupting the audience’s experience. It did not prevent the crew from shooting handheld, but they needed to be mindful of how they moved the camera.

While Fraser enjoys operating, Part Two was a “beast of a film and probably one of the most complicated productions” he has worked on, with many units working simultaneously across multiple locations and demanding virtual location scouting be carried out six months in advance to meet schedules. Needing an exceptional and reliable operator, he contacted Jason Ewart ACO who he has enjoyed working with in the UK on productions such as The Batman.

“The action sequences in Part Two have quite a handheld feel, so we used the Libra remote head and its mimic capabilities to still give the handheld look when we were on the Scorpio cranes, which we worked off a lot,” says Ewart, who is a strong believer in camera movement’s power to enhance the story.

Like Part One, the team turned to the Alexa Mini LF and Alexa 65, marking the fourth film Fraser has shot with the “fantastic” Alexa 65 due to its “unbeatable” sensor size. “The majority of the film was captured on the Alexa 65 because of its IMAX capabilities and ease of framing for both IMAX and 2.40,” adds Ewart. “It’s a bigger camera package than the Mini LF and the conditions we were shooting in were tough, but the results speak for themselves.”

The Alexa Mini LF’s portability and ability to be mounted on the DJI Ronin made it an obvious choice for Fraser: “You don’t choose a format because it’s easy to use, but there are times when it was just more appropriate. For example, we shot the arena fight on the Ronin and key grip Guy Micheletti was acting as a dolly grip and holding the Ronin as I operated. I’d tilt and pan while he was moving and the Alexa Mini LF gave us the freedom and flexibility to be a little less fixed in our approach.”

For the arena fight the Ronin set-up was used with a Tilta Armorman gimbal and a Dragon Grips Precision Track to enable the actors to walk inside the track freely. “This gave us the ability to move left and right, while pulling or following the actors in a low-profile set-up,” adds Micheletti.

As the physically challenging terrain in the desert demanded Ewart “balance on the side of sand dunes, trying to position the camera where it needed to be to help tell the story,” Micheletti and his team created many camera platforms to help the camera operator achieve what was needed in the conditions.

Micheletti tried to keep his approach to equipment, logistics, and manpower flexible and adjustable. “It made it easier to help Greig and Denis’ vision due to their organisation and ability to explain it clearly as well as being open to ideas,” he says. “The desert is always a challenge due to its heat, distances, and terrain. Trying to overcome accessibility and movability is always demanding but with the help of local crews in Jordan and Abu Dhabi, we provided Greig and Denis with the tools they needed.”

An array of sizes and types of telescopic cranes were used including the 75’ Technocrane. “In the desert, to move the 75 more easily and quickly, we converted a mining vehicle into a mobile base for the 75, allowing us to transport it practically anywhere in the dunes,” says Micheletti.

The Chapman/Leonard Hydrascope 43’ was used for shooting the pulling and pushing shots of the spice harvester attack. “We dug a hole in the ground, placed the arm on a bespoke low base, and laid track in the hole. By doing this we could use the 43’s narrow-profile arm with a Libra Mini, keeping the whole arm and camera within the arm’s profile and offering freedom of movement underneath the harvester.”

In another scene, the front platform of the Chapman/Leonard Lenny III arm was modified so it could be mounted to the Baron’s throne, with the Baron’s gimbal rig mounted to hold the Baron so he could float freely. “Jib arms and the Chapman/Leonard Scorpio 45 helped with the movement of spheres in this scene, floating independently from the throne,” adds Micheletti.

The Chapman/Leonard Sidewinder’s heavy arm payload and electronically-driven base was also invaluable for the Baron’s throne sequences. “Because of its size, weight, and versatility we could mount the throne to the Sidewinder’s jib arm,” says Micheletti. “This gave us the versatility to drive freely and jib the Baron’s throne up and down with safety and ease while being creative. We also used the High Sight XL2 cable cam for various point to point shots, and fight sequences.”

Ability to adapt to unplanned situations was crucial when working in remote locations. To capture a long walk and talk featuring Paul, Gurney (Josh Brolin) and Fremen in a canyon, Ewart was hard mounted on a rickshaw with his Steadicam when the rough terrain caused a pin on the Steadicam arm to snap. “As we were so deep in the desert with no back up, the only way forward was shooting handheld – tricky given the rocks and soft sand,” he says. “Thankfully the handheld look enhanced the story, and it turned out to be a much better way to cover the scene.”

As well as providing cameras, ARRI Rental supplied large-format Moviecam lenses – chosen for their vintage optics combined with high-performance housing – to shoot certain sequences. Models from ARRI Rental’s HEROES collection were also supplied including a 57mm LOOK lens with Petzval glass and a 50mm T.ONE lens.

“ARRI Rental have worked hard building up their lens base,” says Fraser. “During testing for The Batman I experimented with a lot of their glass and augmented some of the Soviet era lenses Iron Glass rehoused for shots in that film’s car chase scene.”

The relationship developed with Iron Glass on that production led the cinematographer to choose the company’s Helios 44-2 58mm, Helios 40-2 85mm, and Jupiter-9 85mm, boasting “fantastic rehousing that stood up to the elements when shooting in the desert.” Experimentation with the Helios lenses made it possible to achieve the oval bokeh in scenes depicting Paul’s recurring nightmare visions of a future war.

At the cutting edge

Fraser largely aimed for a natural light feeling, whether working on location or on set. Keen to create “sharp simple shapes” on screen, on occasions he also made use of silhouettes for sequences such as a fight scene shot against a window: “We couldn’t shoot the whole scene in silhouette because we need to see the actors’ faces, but I like using silhouette at times within a complex scene to simplify the image, remove all detail of the characters, ending up with a basic shape.”

Like Part One, predominantly LED lighting technology was chosen for its dimming and colour control, with lighting lessons learnt on the first film informing the cinematographer and gaffer Jamie Mills which fixtures delivered the best results and, when shooting “the desert” on a stage in Budapest, which lights could most authentically make it look like the desert.

“As always, we wanted to push the boundaries of what could be achieved through the lighting,” says Mills. “Creamsource Vortex and Digital Sputnik DS6s and DS3s were two of our main lighting tools. We also built two super powerful sun sources – one with 42 of Aputure’s super punchy 1200Ds. For the other we designed a Vortex 512 through joining 64 Vortex 8s, using Creamsource’s protypes of their now released LNX joining brackets, giving the output of a 100kW soft sun. We also used Rosco’s fantastic handheld lamp the DMG Dash around camera for a hint of eye light.”

Fraser is impressed by the access the industry now has to “incredibly powerful lights” such as the Vortex which offer the “punchy, windproof, weatherproof, powerful and high-quality light” he required. “The Vortex came on the market in the last two years and blew away any expectations we all had about what LED lights do. Their interactive capabilities when running video were also valuable. Thankfully we were supported really well by MBS – an incredible company at the cutting edge of technology who listen to feedback to supply us with the most up-to-date equipment.”

Mills agrees that “as always, MBS was an excellent ally” when servicing the film: “Logistically, this was a tricky production to service and trucks regularly did the long drive from the UK to deliver lamps and equipment, sometimes several times a week.”

As the production traversed four countries, Mills worked with a different gaffer and their crew in each location. “The bulk of the work was done by gaffer Krisztián Paluch who also helped me on Part One along with his incredibly hard-working team in Budapest, where all of the sets were built,” says Mills.

One of those sets, the Emperor’s throne room, featured a complex lighting set-up of sharp top light whilst avoiding multiple shadows being created. The crew also faced the added obstacle of the set being built in the exhibition centre “with lower than ideal ceilings”. The rigging team, headed up by rigging gaffer Ben Wilson and HoD tube rigger Paul Garratt, devised a way to rig two very long strips of Vortex 8 fixtures in the ceiling structure of the building, while steering through a myriad of steel structural beams. “The lighting for this had to be extremely precise to create a perfect cross of light on the floor,” adds Mills. “In the testing phase, we experimented with many different lamps and flag and teaser ideas before settling on the Creamsource Vortex 8s and a 10-foot teaser on either side with a one-foot opening to create the desired look.”

Elsewhere, Aputure 1200Ds were used to create shafts of light through the holes in the communal dome room and a wall of Creamsource Vortexes produced the “anti-light/flashing effect” Villeneuve desired in the Giedi Prime palace corridor down which Feyd-Rautha walks after the arena fight.

The expanded scope of the story required more complex lighting for larger scale sets such as the tunnel entrance to the atomic vault which demanded Mills and his team create a banded light to simulate Gurney throwing globes in to illuminate the tunnel. “After failed attempts using conventional lighting, I thought about how some car front fog lamps create a beam of light to illuminate the roads,” says Mills. “Mike Forster, head of practicals, discovered an old motor parts shop in Hungary selling older style car lamps which we used to build a unique lamp structure and rig to a camera crane to create the desired effect.”

Space to create

Fraser and Villeneuve identified key “make or break” scenes early on to which sufficient time and resources would need to be allocated. Paul’s unborn sister Alia – who can communicate with her mother Lady Jessica from within the womb – was a new and exciting aspect of the story to which ample time needed to be dedicated. Models of the foetus were created before the crew lit appropriately so they could be photographed to feel like they were in a womb.

“On paper the foetus might not look like it would take long to shoot, but Alia is a character and it was important we spent more than a day getting that action right. Another example is the sandworm riding scene which would have only been four or five days in our schedule according to the number of pages in the script, but we knew how important it was to get correct, so we started shooting that scene before principal photography began,” says Fraser, who worked with second unit director and producer Tanya Lapointe, second unit cinematographer Daniel Vilar, and B and C camera operator Kristof Brandl to achieve the shots needed for the sandworm riding scene.

Having established a productive way of collaborating with Fraser over the past three years, Vilar believes part of the film’s success is down to Fraser “seeing the second unit as a necessary extension of the main unit that can contribute on equal measure in terms of value but just on a different orbit.” Responsibilities of the second unit included technically challenging shots in scenes requiring weeks of preparation such as the harvester attack or a small insert for a larger scene Fraser shot such as the Muad’Dib drinking the Water of Life. Vilar refers to Villeneuve as “a force of nature with a passion that is so contagious you can only put your heart on every shot like he does” and Lapointe as “a director with a great instinct and powerful determination who understood better than anyone what was at stake in every scene.”

Vilar continues: “The sandworm riding scene has a lot of importance in the story and became so technically challenging and slow to shoot we had to split the crew to have a dedicated unit working for weeks exclusively on it. The young and talented camera operator Kristof Brandl was executing it for most of the time and I took over when we moved to the desert.”

While Villeneuve tries to shoot as much as possible in camera, the work of Paul Lambert – a visual effects supervisor the director refers to as a “magician” – on both films ensured his vision was realised on screen. “There are many things we can do in camera but a battle of sandworms fighting against an army of Sardaukar? That’s where I reach a limit, and that’s where I really need Paul’s genius,” he says.

“How incredibly well integrated the effects were is testament to Paul and his team who made sure it’s shot the right way. It’s easy on set to say, ‘We’ll just shoot against a blue screen, and fix in post.’ But the reality is, that doesn’t work. It’s got to be lit accurately and the action has to feel believable, so the lighting and staging needs to be correct before post to be successful which Paul never compromised on,” says Fraser.

“I love working with Paul because when making both films, he was always the guy in meetings who would say, ‘We need to do it this way because the lighting is more accurate.’ I’m normally that guy.”

Sci-fi that soars

Aerial cinematographer Dylan Goss and his team continued their work from the first film, from capturing sequences of ornithopters and other flying vehicles in the sky through to sequences asking for more slight moves, “working the rocks for backgrounds to place figures as they ascend into battle”. Three Shotover K1 gimbals allowed everyone to shoot in two countries back-to-back while they extensively used a built-to-spec three-camera array, with all aerial gear coming from Team5 in Los Angeles, along with support from the US and European arms of ARRI Rental.

“We did a lot of un-typically cool shots with the aerial package, such as for the insane look Greig was creating for the eclipse scenes using IR-pass filters. We followed suit, including using Moviecam primes and the same filtration, which was really nice to be able to do in-camera from a helicopter,” says Goss. “Greig embraced some imperfect optics, and with his support that led to us at times using both an older ARRI 765 zoom as well as wild stuff like a Canon FD 150-600mm I found that was rehoused by Century Precision. Such extra-large lenses for a helicopter required custom bracing and shrouding and really became one-off type of installs.”

For the more traditional aerial shots of spacecraft flying, Goss and his team had full backing of visual effects supervisor Lambert to shoot the sequences with proxy helicopters standing in for various story vehicles. “The technique of having a real aircraft play the part of an ornithopter, for example, not only motivates my operating but adds an organic nature to what might otherwise end up a sterile plate,” says Goss. “There is real object lighting in there, as well as atmospherics. There are just so many reasons to work this way when possible, but it takes a project of a certain scale and creative ambition such as Dune: Part Two to employ the multiple aircraft and flight crews required to do it.”