LEADING LIGHT

From intricate illuminations through to ambitious camera movements, Sir Roger Deakins CBE BSC ASC shares insight into the creation of scenes from a selection of films he lensed, along with lighting diagrams, sketches and location photos.

No Country for Old Men (2007)

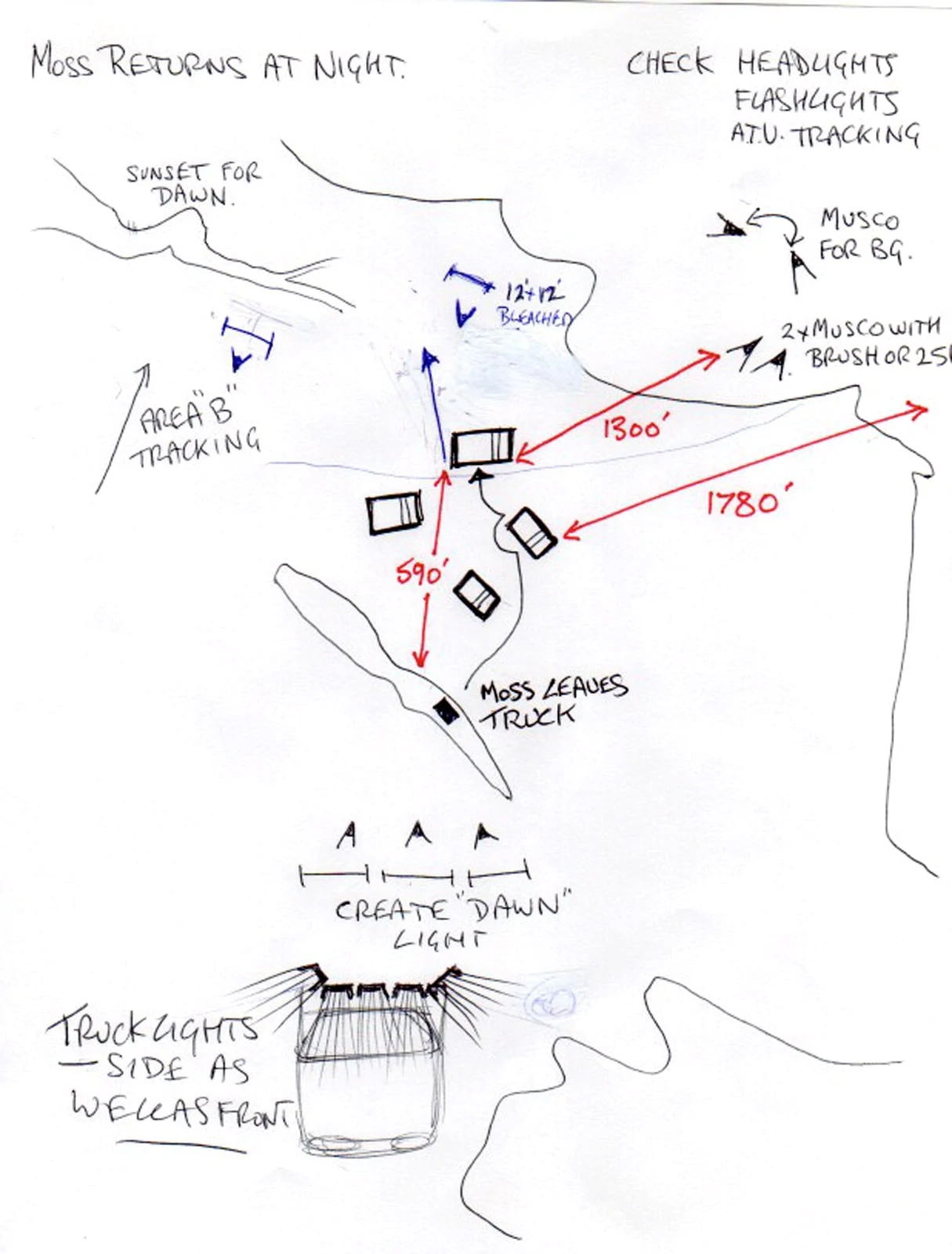

Lighting the basin at night

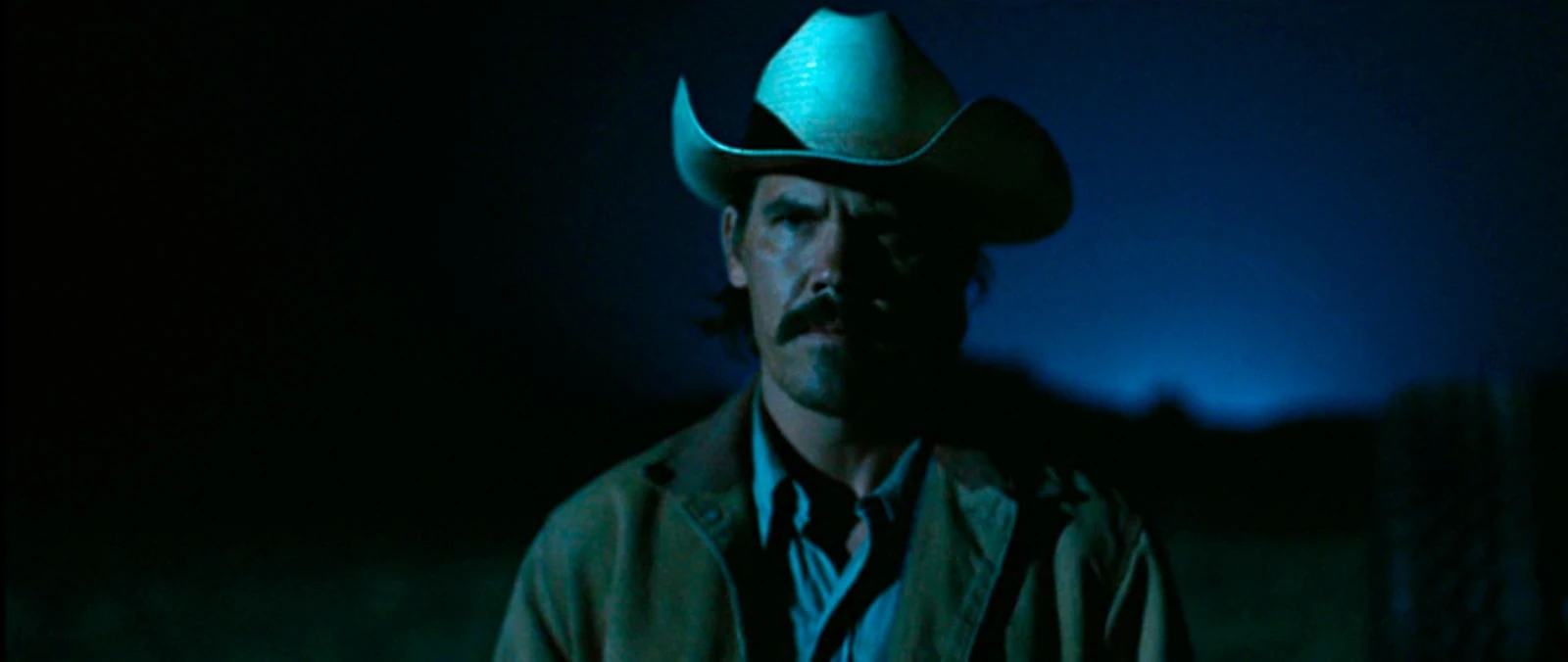

The largest and most daunting scene for me in No Country for Old Men was when Moss (Josh Brolin) returns to the aftermath of the drug deal and his one moment of kindness starts him on his inevitable last journey.

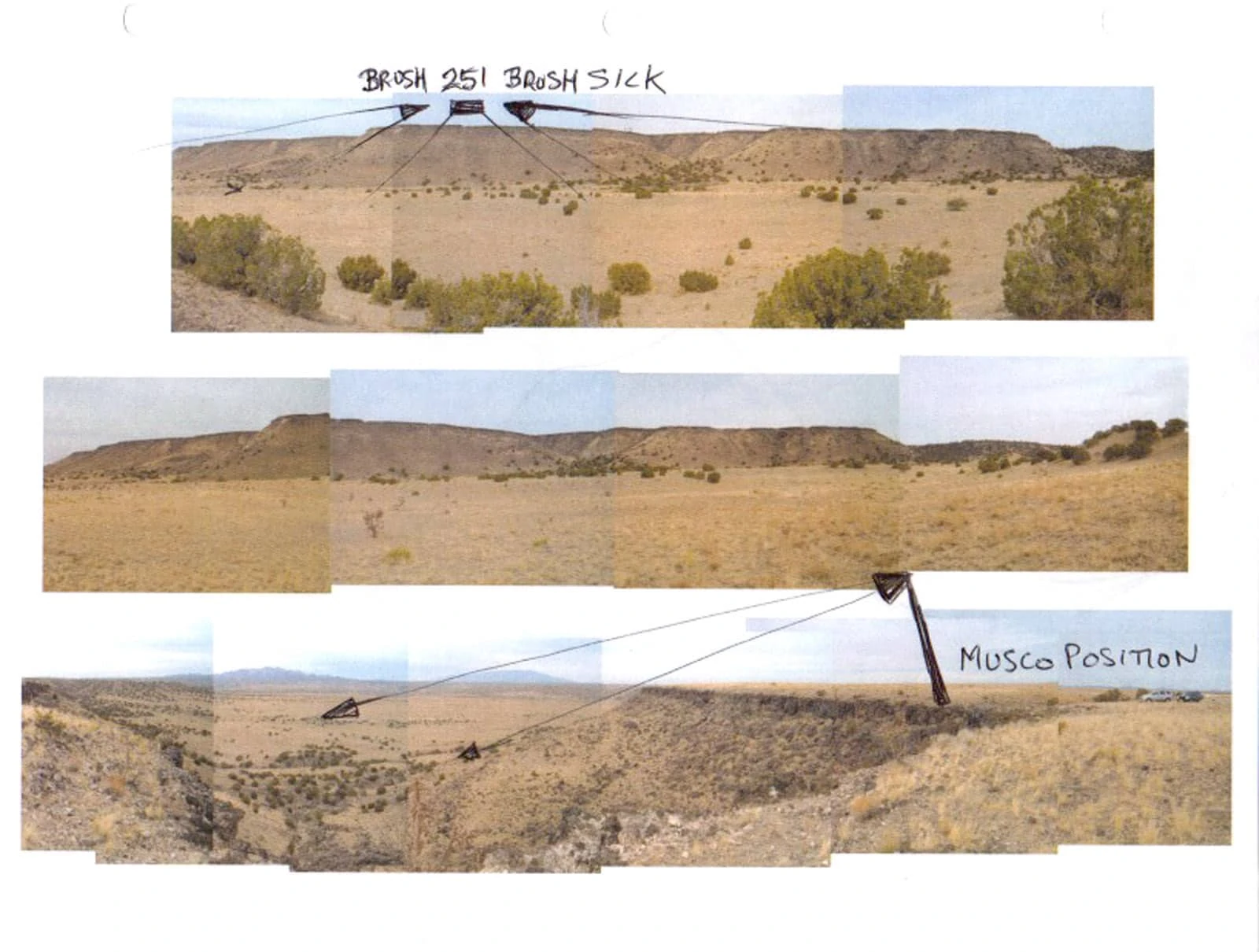

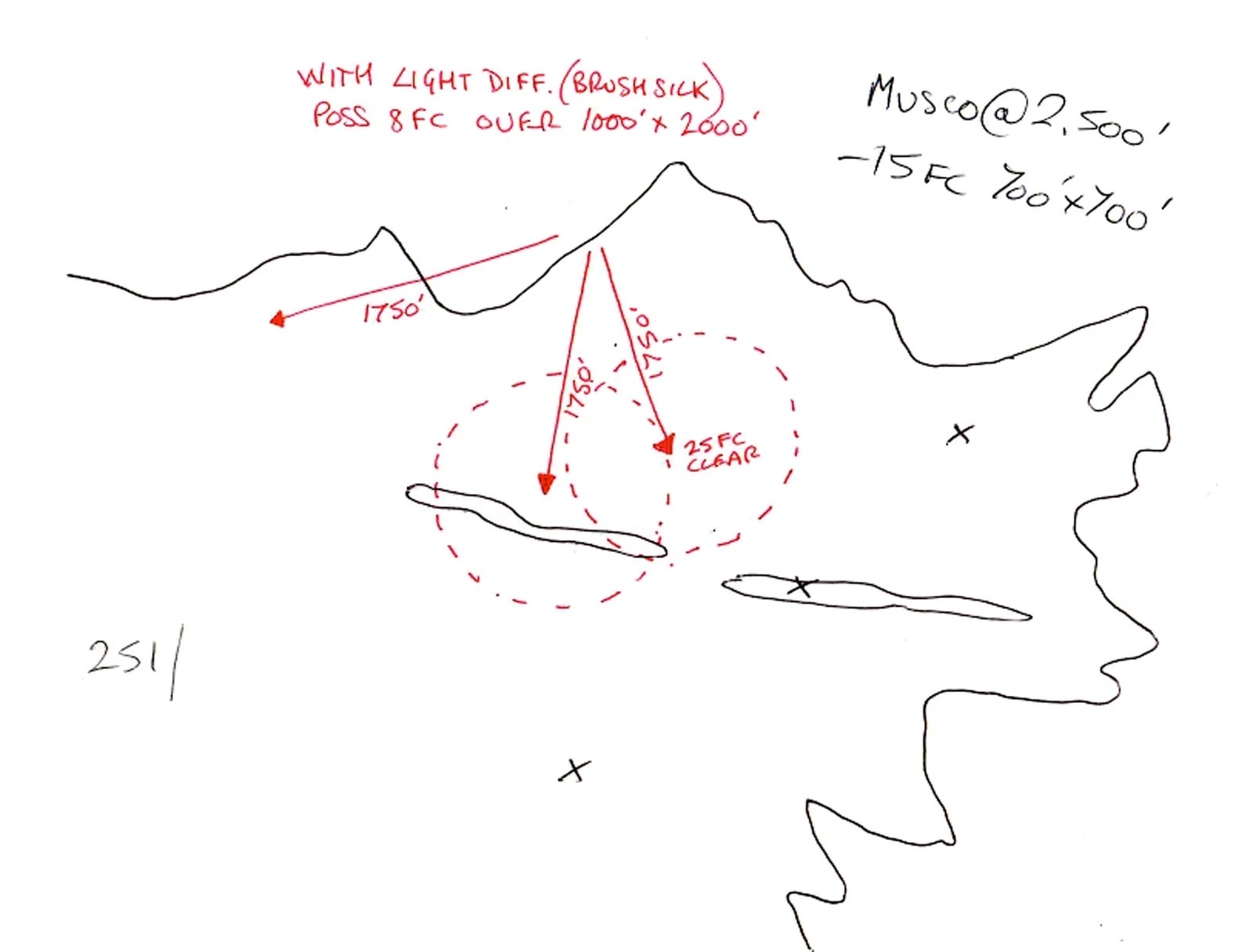

The location for this scene was chosen for the view it offered from the bluff as well as the geography of the terrain in the basin below. The whole layout of the landscape was very important to directors Joel and Ethan Coen. Beneath the bluff they needed a small hill on which Moss could park his truck and beneath this very specific areas over which the action could evolve. This action needed to continue across a sloping plane to where there could be a river, which for various reasons needed to be at an entirely separate location.

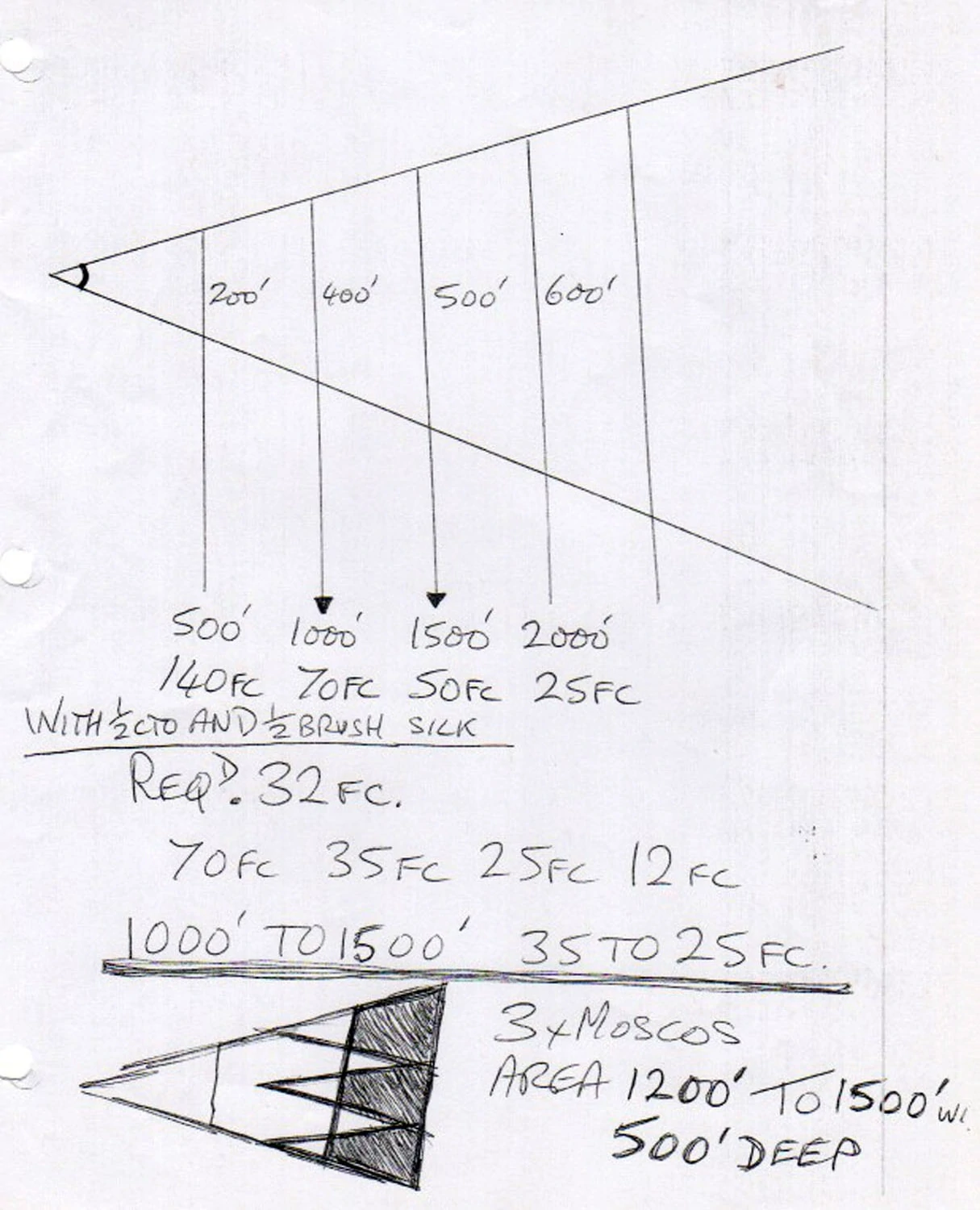

For me, the challenge was in lighting such a large area at night. My preference would have been to create a soft ‘moonlight’ effect, such as I attempted some years later on the film True Grit. However, given the space involved, it was going to be a challenge just to get an exposure on a 500 ASA film stock, even with Zeiss Distagon 1.3 lenses. At the time I had begun shooting with the Cooke S4 lenses, which I loved the quality of but were a 2.0. An additional complexity was that the script called for dawn to break from the time that Moss is discovered, part way through the scene.

As you can see from the diagrams, the space I had to light was quite large and it was not just a matter of lighting the human characters and allowing the background to go into complete blackness, as the landscape surrounding the action was a character in itself. Using the bluff was my solution. By placing my ‘moonlight’ there I could wash the whole area with a light that acted as a sidelight or a backlight but rarely as a front light. Of course, one of the real advantages of storyboarding a scene like this is that you can consider these parameters beforehand. To move such a lighting set-up as I needed here would have been two days’ work, so I had to be sure I had chosen the best option.

I had used Musco lights before, for some quite similar scenes in a film called Thunderheart, so I knew these units would be viable on this location if we could only gain access and permission to use them. Luckily, the land above the bluff was relatively flat and firm so to drive these vehicles into place was not a large problem. Failing the Musco lights, I had considered erecting a large high scaffold to hold a line of 12K HMIs. A Musco is basically a large crane holding an array of 16 x 6K HMI lamps, which give an output of 96Kw. The output from three such units would be around 288Kw, so a simple equivalent in terms of wattage would amount to 24 x 12K HMI lamps.

The problem would be the time taken to rig the scaffold and this number of lamps because our schedule just did not allow for that. Besides, I would not have very much flexibility during the shoot with fixed lamps, even with a much larger electrical crew. By using the Muscos I already had the lamps on a 100’ arm and each lamp could quite easily be re-focussed from the ground using a tried and tested remote control unit. The cost of the three units was pretty steep but compared to the rigging and derigging that would have been required for any alternative, it didn’t seem such a bad choice. As always, we had a lot to shoot in a short period of time and it was mid-summer, so the nights were short.

Musco lamps are usually used to light stadiums and concerts rather than being specifically designed for film work, so it was understandable that we needed to adjust our schedule for the availability of the units. In the end, because of cost and availability, I was restricted to using two of these units. On the night before shooting, my pre light night, I was standing below the bluff taking a light meter reading and it was quite apparent why I had initially wanted the three units. I had ordered in some extra HMI Par lamps but my meter hardly moved.

On the ‘floor’ we used large bounce sources to ‘catch’ the available light and to wrap it into a face. Sometimes I used an extra lamp, perhaps a 400w Joker, to add to this soft wrap.

For the dawn silhouette effect that outlines Moss’s truck on the hill we used a line of about 7 x 12K HMIs behind the hill and simply pointed them at the sky. There was a long strip of duvetyn acting as a cut to the bottom of these lights so that nothing direct interfered with the ground. I tried a little smoke to enhance this effect but as this didn’t look right, we spotted in the lamps and simply allowed what dust was in the air to create the silhouette. We had staged the action as best we could so that the true dawn would rise in the same place relative to the camera as the artificial one but, as luck would have it, it was cloudy when we shot. Consequently, the blend is not so good. So it goes!

The last sketch of the final lighting in fact changed yet again! The HMIs used for the dawn effect behind the hill on which Moss parks his truck are marked on this diagram to be bouncing. This might have worked if we could have used smoke, but as we were just lighting the air and whatever dust was naturally in it, we used direct lights.

True Grit (2010)

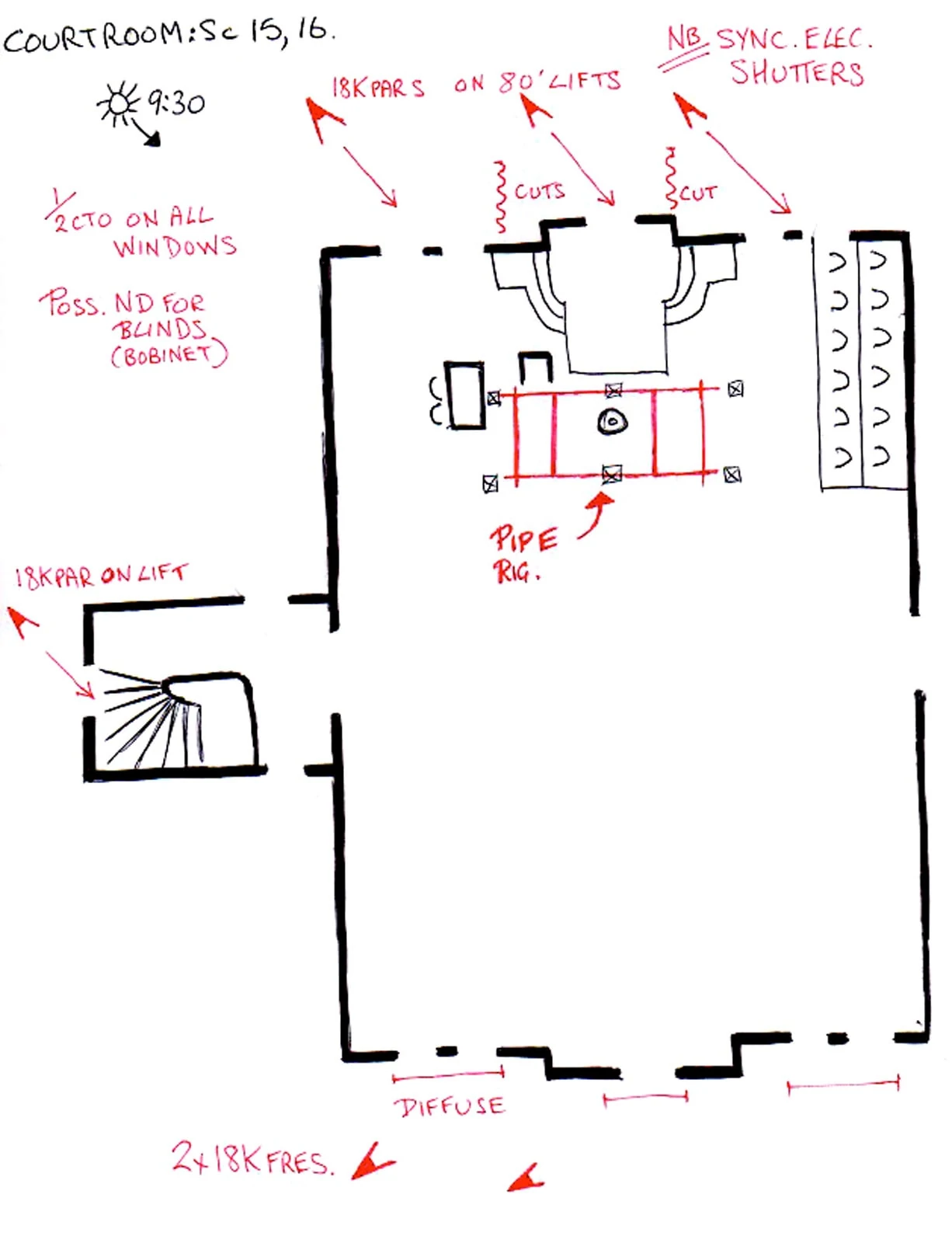

The courtroom scene

The courtroom scene in True Grit was shot in a room on the second floor of an old town hall.

Joel Coen had given me a brief to hold Rooster (Jeff Bridges) in shadow until Mattie (Hailee Steinfeld) moved closer to the front of the spectators. I decided to create the effect of hard sunlight streaming through the windows that are behind Rooster and allow for bounce light to wrap around his face from Mattie’s forward position.

The problem we faced in lighting this location was that the windows I was going to light through faced south and this necessitated not only lifts of some kind to carry lamps but also lifts to carry large solids to cut any natural sunlight.

The yellow blinds were designed for the windows to cut down the opening through which the artificial sunlight was falling but also to heighten the feeling of the warmth and intensity of the light.

The location photo shows what we started with, followed by the lighting diagram, and then a frame of the final result.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

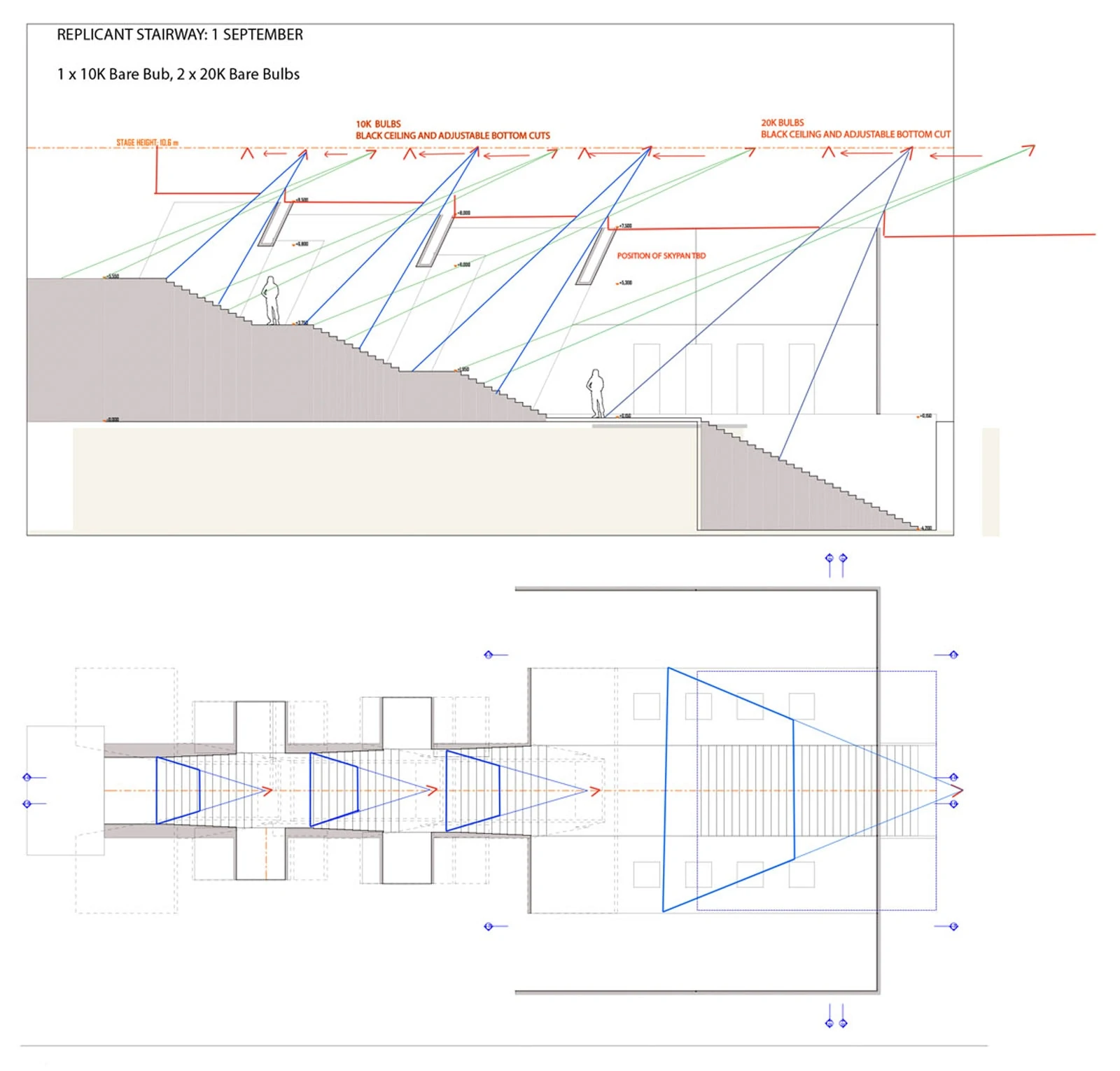

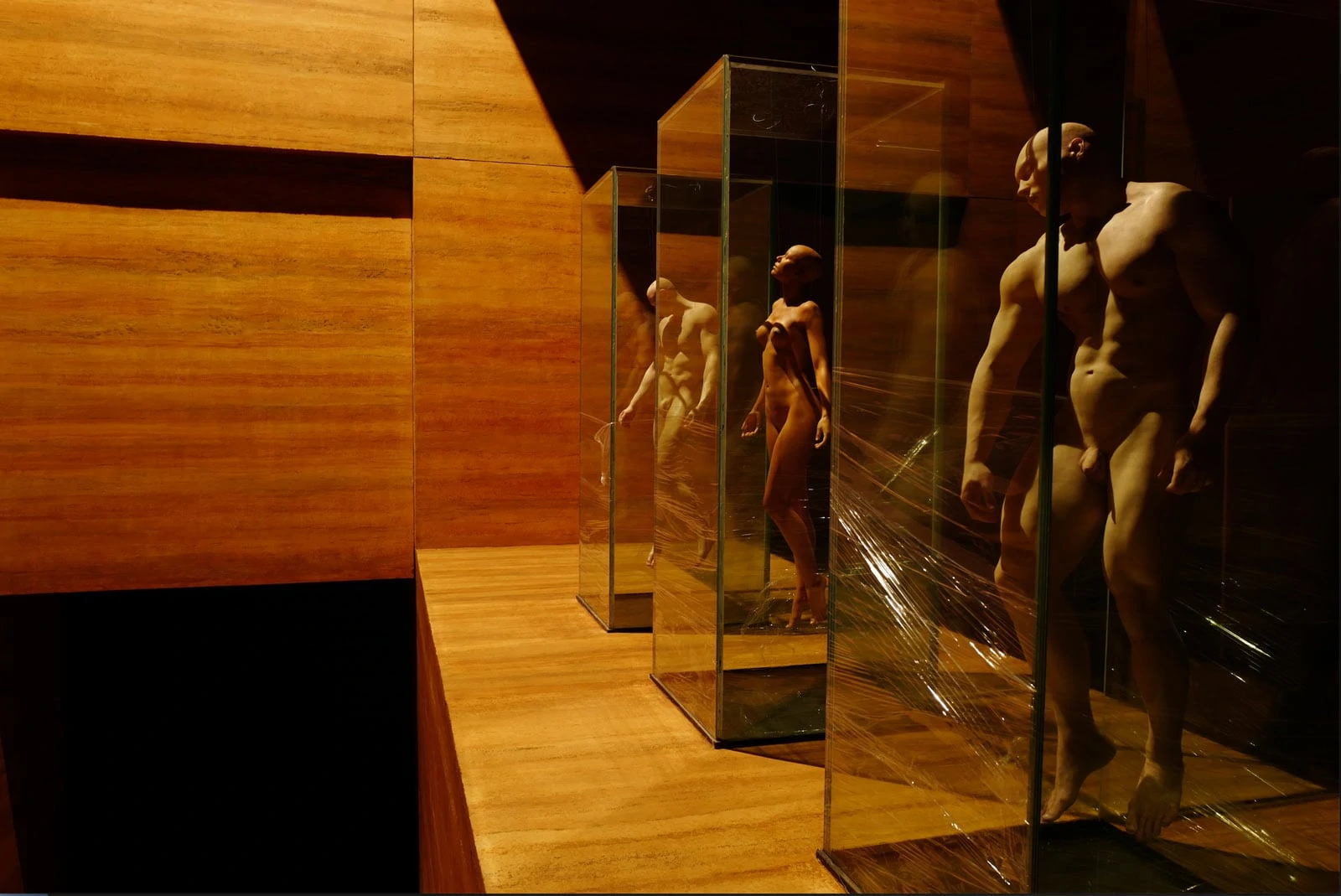

The replicant stairway

As this scene is part of our discovery of the interior of the Wallace building, I wanted to maintain the idea of moving sunlight.

The first element for discussion with the art department was the height of the stage and, given that we did not have a stage with enough height to cover the set with a single source of light, there needed to be adequate room above to create a hard pattern of light using a series of individual sources. For this I needed to have defined openings above the stairway that could be separated from one another. By looking at various plans we felt the best option was to construct the set so the camera would never see the ceilings. This would allow me to control the size of the openings using cutters rather than working with a hard ceiling that would be fixed in place.

For the source of the light my gaffer from the US Bill O’Leary was able to obtain some 24K bulbs, such as are used in a Skypan. Rather than using the Skypan itself Billy used just the socket for the bulb and had this welded to what amounted to a dolly, which could run whilst attached upside down to a length of pipe. The pipe was then rigged as close to the stage ceiling as was possible. A single 24K bulb lit the largest space, where the replicants are on display, whilst three 10K bulbs were used above the stairway leading down to this space. Each rig ran separately along the central track and each was slid along by hand. It was all very low tech really, but the idea of a computer-controlled track seemed a little like overkill for such a short scene. We practiced coordinating the movement of the four lights a number of times before I felt the effect was working in a seamless way. Billy, our Hungarian gaffer Krisztián Paluch and I each breathed a little easier once this scene had been shot, but I guess you could say that about every scene!

1917 (2019)

Complex camera movements and naturalistic lighting

Sam Mendes and I spent months talking about the script for 1917, what the environment should be, how to move the camera and what the feel of the camera movement should be. At one point we were even talking about shooting it handheld but decided against this because there was something about the camera being solid and relentless that worked well.

We did an awful lot of prep and tested all sorts of equipment – all the new stabilising systems and different kind of rigs – to find a way of moving the ARRI Alexa Mini LF, switching between modes of operation. Working closely with Pete Cavaciuti, a Steadicam operator and good friend since my rock video days, we explored different rigs and came up with the core methods of moving the camera. One was a new development called the Stabileye. This completely remotely operated head would either be on a crane, handheld by the grips or on a little post that Pete came up with called the Dragonfly. It’s like a Steadicam post the Stabileye system goes on and Pete would run with. Rather than looking at the image, he would position himself where he needed to be, and I would operate remotely. We also worked closely with Charlie Rizek who is a master of the Trinity, the very sophisticated Steadicam with a small jib arm allowing the camera to go from ground level to above head height. Working together we practiced with the different rigs and settled on the three major ways of working. Outside of that, there was a small amount of drone work.

I then went through the script with Sam Mendes, talking about where we would put a break and what we could achieve in one shot. We looked at which section we could shoot on a certain piece of equipment, what Sam was comfortable with in terms of the actors and what we were technically comfortable with. I created a spreadsheet, breaking down the film in terms of the equipment we would use. James and I worked with that to create a schedule of what equipment we needed on which day, who would operate it and how we would achieve what we set out to do. For instance, sometimes the camera would be on a Stabileye but two grips would run with it on a pole. They would then clip it onto a Technocrane which would take over. Sometimes the Technocrane would be on a tracking vehicle which would take off and then the shot would become something else.

We practiced an enormous amount with many pieces of equipment to figure out which best suited a particular piece of action. A couple of times the Stabileye system was handheld and then clipped onto a wire rig which would take off and follow the actor, whether it was across the bridge or over the shell pit in no man’s land. That was all done on a crane, but to get there the grips handheld the rig and clipped it onto the crane before the crane moved off. Sometimes Pete walked backwards onto a tracking vehicle which would take off. When it stopped Pete would get off and follow the actor. For me, some of the amazingsequences were done by Pete on Steadicam – he’s such a brilliant operator.

We faced many challenges but one scene that is interesting to highlight takes place early in the film when the two main characters – Lance Corporal Blake and Lance Corporal Schofield – move from the field down the trench line and into Erinmore dugout which is lit with oil lamps. The camera then becomes solid and its movement through the scenes is choreographed with the actors’ movement. It then moves in a full 180, looks back at where it came from and pans with the two main characters as they leave through the door.

This involved the camera being underslung from a Technocrane that is booming out over the set, through a hole cut in the ceiling. The camera tracked forward on the dialogue and as the characters turned around, I remotely panned the camera around. As it turned around, key grip Gary Hymns, took the camera off the crane and walked with it, holding it steady for a wide shot for the end dialogue before quickly moving around and following them as they start walking up the steps out of the bunker.

On top of the camera movement, lighting that scene was also a challenge because there was no way I was going to put a lamp in there. I didn’t want the feeling of artificial lighting because the whole film is very naturalistic. For the day exteriors I never used any lighting but for the night scenes we obviously used a lot. In fact, for one scene – the church sequence towards the end – gaffer John Higgins and I used more lights than we ever have on any one scene.

But for Erinmore’s bunker, we just used little lanterns. John and I worked out that each lantern had two small quartz bulbs in it in line with where the camera would be looking. So, when the camera was looking one way, the bulb that was off camera, or the far side of the camera, would be higher on the dimmer, and the one that the camera was directly looking at would be dimmed down. It was all about flagging the brighter bulb, so it wasn’t flaring the lens. So as the camera moved past, the light would subtly shift on a dimming board and as the camera did a 180 and was looking back the other way at the same lanterns, the relationship between the two bulbs went in the opposite direction. If you’d had them at full power, with the camera pointing at it, there would have been all sorts of flares. In that scene there was all this dimming going on at the same time as quite a complicated camera movement. In the film it looks fairly simple, but it wasn’t!

> GO TO SIR ROGER DEAKINS CBE BSC ASC: ‘CREATIVE FORCE’

> GO TO OUR ‘HOME’ PAGE

> BACK TO TOP