Netflix’s Don’t Look Up follows two academic astronomers who, after discovering a comet destined to destroy the Earth within six months, must go on a giant media tour to warn humankind. The film was directed by Adam McKay with cinematography by Linus Sandgren FSF, ASC. The film was graded by Matt Wallach at Company 3 using DaVinci Resolve Studio editing, grading, visual effects (VFX) and audio post production software.

Wallach had primarily focused on dailies colour in recent years working with many top cinematographers, including Sandgren who likes Wallach’s approach to colour and asked that he do both dailies and final colour for his previous film No Time to Die. Sandgren prefers to shoot film negative whenever possible, as opposed to digital acquisition, and to treat digital colour grading with an eye for always preserving the filmic look of the images. He also likes to approach colour in ways that hold to the feel of photochemical work.

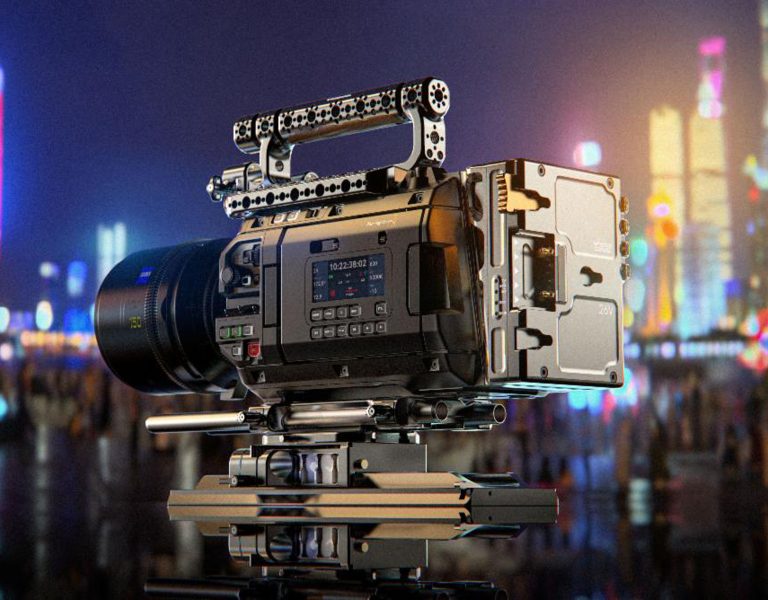

On Don’t Look Up, Sandgren shot with a range of formats, in addition to film, which added to the complexity of the grade. “It was predominantly a 35mm show but there was some anamorphic, some spherical, some Super 8 and a little bit of 16mm,” said Wallach. “There was also a lot that was shot with digital broadcast cameras in a studio type space for when characters are appearing on TV.”

Wallach suggested an approach for grading those scenes. “The idea that I presented was when they come to the broadcast portions, we should go for this hyper saturated look, almost like you’re walking through an electronics retailer and you see all these TVs in ‘display mode,’ where it’s just really bright and vivid, and there’s something a little uncomfortable about it,” he explained.

The challenge with these elements was the lack of a log file for grading, which can make a more intense look harder to achieve. “The broadcast footage wasn’t scans of raw files. It was shot in Rec. 709 colour space, and it sort of is what it is,” added Wallach. “I initially approached it similarly to the rest of the material using offset and printer lights. Then once everything was balanced, we pushed the contrast and saturation and used several different curves within Resolve to see how far we could go until the image started to deteriorate.”

Additional challenges included the large number of VFX in the film, not simply big CG shots but also subtle work not as obvious to the viewer. “There were quite a few shots that may not have been VFX shots to begin with but became VFX shots because of the pandemic,” said Wallach. “There were limits to how many people could be on the set at any given time, including actors, so some setups became multi shot composites.”

The VFX team provided CG crowds, and with 2D locked off elements and volumetric capture, the scene could be expanded from the available 25 or 30 extras on set to a crowd of 100 or more in the frame. “For some shots, like in the concert and the rally scenes, there was a lot of digital crowd replacement to make them look full,” explained Wallach. With the use of mattes in DaVinci Resolve Studio, Wallach was able to balance the elements to ensure the dynamic lighting that splashes across the audience seamlessly matched between elements and looked natural.

Wallach appreciated the tools available in DaVinci Resolve Studio, which helped him be more efficient when managing the grade. “I used the colour warper tool, especially when matching in stock footage. I could have combined other tools to do the same work, but the colour warper was very efficient for collaboration because I could change different parameters at the same time and show Linus how the image was affected in real time. When we were cutting back and forth between the film and the TV studio material, for instance, if we wanted the reds in the TV parts to be in a certain place, I could just grab those reds and push them in the right direction in a single move. I could make a global change more quickly than if I tried to do the same thing with keys or curves.”

Netflix gave the film a theatrical release alongside its distribution globally on the service. This meant access to both high dynamic range (HDR) and DCI-P3 finishing tools. “I used the HDR wheels within Resolve quite a bit for the HDR passes of the film as opposed to using log wheels and curves to help control highlights,” concluded Wallach. “It really made up for the HDR trim process since the theatrical P3 was our hero grade. There’s a flexibility with the HDR wheels of being able to set the affected range for each zone and then just control the exposure of those zones individually. I think that the HDR wheels help you get to the desired place for your HDR versions in a simpler way than was possible previously.”

Don’t Look Up is streaming now on Netflix.