The Dark Side

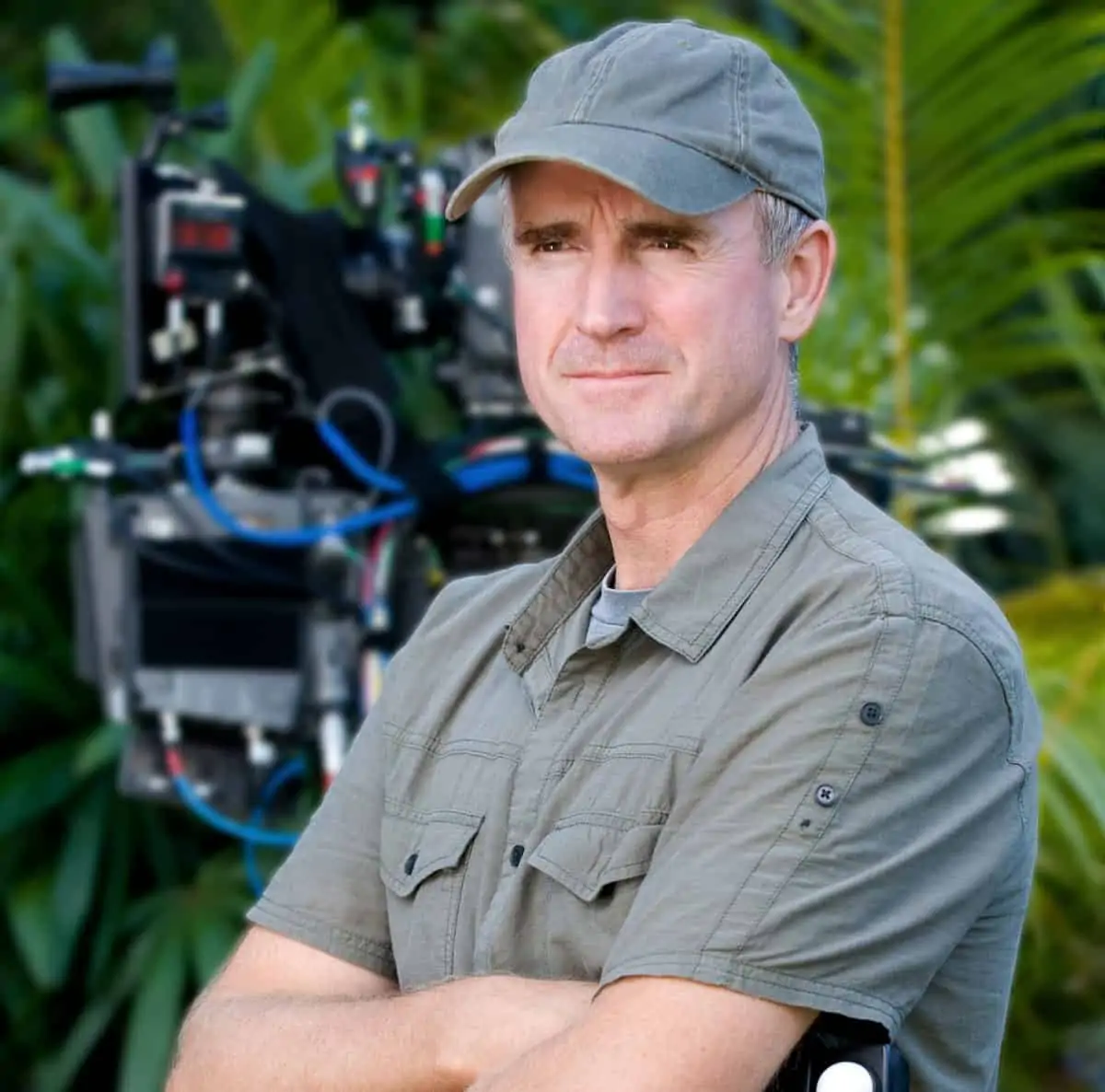

David Tattersall BSC / Death Note

The Dark Side

David Tattersall BSC / Death Note

“It’s a bit different for sure,” says cinematographer David Tattersall BSC about Netflix’s Death Note. “An R-rated, wish-fulfilment, teen-horror with a detective-thriller twist and plenty of blood and guts – the kids are going to love it.”

Directed by Adam Wingard, and based on the manga series of the same name by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata, the full-length feature follows Light Turner, a high-school student who comes into possession of a supernatural notebook, called Death Note, which grants him the power to kill any person simply by writing down their name on its pages. Able to converse with Ryuk, the demonic god of death who created the tome, Light decides to use his new potential to kill criminals and change the world, thereby becoming a notorious serial killer. But an enigmatic detective is hot on his trail and is determined to end his reign of terror.

Tattersall had previously worked with Wingard on the pilot of Outcast in 2015, Fox’s successful supernatural TV series, and their collaborative experience was such that the cinematographer was invited to shoot Death Note. Production began in British Columbia in June 2016, at locations around Vancouver and on sets built at Northshore Studios.

“Adam loves this genre, and has plenty of experience working on the dark side,” says Tattersall. “I had only dipped my toes briefly into horror before but wanted to explore it more. I also have a soft spot for Vancouver, where I shot The Day The Earth Stood Still (2008) and Tooth Fairy (2010), and had a great experience working with the Canadian crews there.”

Aesthetically, Tattersall says that Wingard knew precisely what he didn’t want for Death Note – no handheld – preferring something more controlled, yet determinedly gritty and hair-raising by using other shooting and cutting techniques. During pre-production the pair would settle down together, several nights every week, with a selection of DVDs and revisit sequences they both remembered from movies that might prove inspirational.

“We checked out Fincher’s fine work in Se7en (1995, DP Darius Khondji AFC ASC) and Fight Club (1999, DP Jeff Cronenweth ASC), along with Kubrick’s The Shining (1989, DP John Alcott BSC) and Clockwork Orange (1971, DP John Alcott BSC) –

We also zeroed in on a handful of well-crafted sequences from classic movies, such as The French Connection (1971, dir. William Friedkin, DP Owen Roizman ASC) and Taxi Driver (1976, dir. Martin Scorsese, DP Michael Chapman ASC). The cool textural tones in these movies gave us some clues for how we might approach our more sinister moments and particularly the elaborate foot chase in our third act.

“A further key consideration was how best to ramp-up the terror surrounding the appearance of Ryuk. Having watched Jaws (1975, DP Bill Butler ASC) and Alien (1979, DP Derek Vanlint), we landed on a less-is-more approach, the less you see of him, the more effective and unnerving the moments he appears will be.”

Tattersall says a key influencing factor for the look of the production came from the location choices – in some of the more down-and-out parts of Vancouver – such as the warehouse district, with its dingy alleys, old diners and dilapidated hotels, he knew he could enhance the existing industrial sodium vapour lighting with contrasting greens and blues, “for a more edgy result.”

"I have to say that we ended-up falling in love with the look of the Panasonic 35, and used it for 95% of the show, only occasionally using the Phantom Flex for super high-speed 500fps moments. It has a lovely, soft, realistic creaminess to the image that comes closest to the Alexa."

- David Tattersall BSC

In keeping with the thrilling nature of the action, the pair also decided to imbue the imagery with a shallow depth-of-field, from a mixed use of both extremely long focal length lenses with very wide distorting lenses and very low light levels.

Being a Netflix show, it was dictated from the start that Death Note would be a 4K production. “The industry has fallen in love with the ARRI Alexa, but as it is defined as a 3.2K camera, we had to test the range of Netflix-certified cameras,” he reveals. “The Reds, Sony F65 and Alexa 65 all produce great images, but after conducting side-by-side comparisons on a big screen and considering our subject matter and location working environments we settled on the Panasonic 35 (since rebranded as the Panasonic Pure). It has a lovely, soft, realistic creaminess to the image that comes closest to the Alexa. I have to say that we ended-up falling in love with the look of the Panasonic 35, and used it for 95% of the show, only occasionally using the Phantom Flex for super high-speed 500fps moments”

Tattersall opted to pair the Panasonic 35 with Zeiss Master Prime spherical lenses, shooting for a widescreen 2.39:1 extraction. “The Master Primes are superb. The Zeiss lens designers cracked it with this range of focal lengths. It’s nice to have T1.3 in your back pocket when you know you have a lot of night work coming up.

“Our basic rules for dialogue coverage were fairly conventional, a 40mm for medium shots and 100mm for close-ups, but when Ryuk appears, and for all of the flashbacks, we ramped-up a more expressionistic approach. Using the 14mm on a roll-over rig or the 12-1 zoom with a doubler.

“Also on a practical level, compared to the Anamorphic equivalents, the Master Primes have a flatter look with minimal distortion. Shooting spherical and framing for 2.39:1 is often the preferred source material for VFX post later on.”

Whilst it had been decided to show only brief glimpses of Ryuk – such as a silhouette, or showing just details, a hand or red eyes emerging from the darkness – to raise the dramatic ante, Tattersall turned the dramatic tension a notch higher, by also introducing what he calls, “some funky, far-out photography.”

As he explains, “A scene might start with normal coverage and a regular dolly move, but as the moment of extreme terror or graphic violence developed, we would introduce our distorting filters and roll the horizon over to one side or another, to create a sense of discomfort and heighten the supernatural.”

Using a P+S Skater Scope allowed Tattersall to pivot the lens block and thereby rotate the picture, sometimes a full 360-degrees, often getting to within half an inch of the ground. On other occasions, a Lensbaby was used to change the axis of the focal plane, to give a selective focus and blurring.

“We really messed around with the image,” he says. “One of our favourite and most effective tricks was to smear Vaseline on an optical flat to flare specular highlights. Sometimes the old tricks are the best.”